Yes, in a sense we are all Biafrans

It is not just the Biafrans. There are widespread perceptions among virtually all Nigerian groups that they are marginalised and they seek redress in a new Nigeria. The reason for this is the supplanting of federalism with a Jacobin unitary state. The erosion of multiple poles of political power by military dictators and subsequently by an all-powerful presidency has exacerbated the spectre of the fear of domination everywhere in the country.

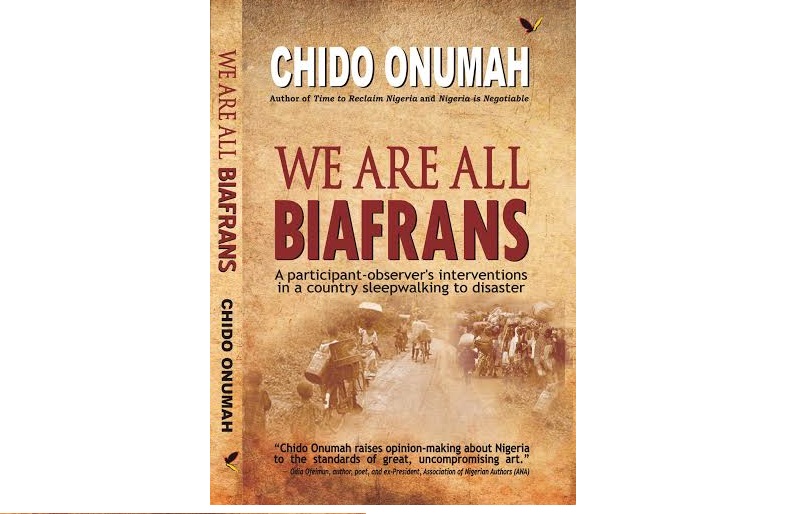

On May 31, my good friend Chido Onumah made a public presentation of his book, We Are All Biafrans. The book is a passionate plea to all Nigerians to work together to ensure that we stop “sleepwalking to disaster”. The discussions on the book in the media were completely overshadowed by former Vice President Atiku Abubakar’s support for the political restructuring of the country, expressed in the same event. Chido makes the case that we need to renegotiate but it should not be done “solely on the basis of ethnic, religious or cultural affinity”. Biafra, he argues, is not an “Igbo problem” but a Nigerian one and the way forward is to build our federalism along civic lines and on the basis of “justice and equal opportunities for all”. I completely agree with the argument. Nonetheless, the discourse of marginalisation has permeated Igbo consciousness, just as it is the case for other Nigerians and the issue of unpacking ethnic narratives is extremely important.

I tried to do so in seven articles on marginalisation as perceived by Nigerians in the six geopolitical zones between October 29 and December 17, 2012 and the articles did not raise a ripple. Following the rekindling of the Biafra question by IPOB and others, I returned to what I called the Igbo Question on November 30th, 2015 and this time, I got the bashing of my life.

One of the issues raised was how can I dare to tell the Igbo story. The famous blogger, Victoria Ohaeri, put it this way: “There are five main reasons why Sir Jibrin’s (I don’t know when she gave me the knighthood) article warrants a duteous rewrite, or at best, an outright retraction. First, the growing tradition and bourgeoning number of outsiders telling the Igbo story, rewriting their history and shoving down their squinted narratives as legitimate accounts of Igboism is something to deeply ponder about.

“To be clear, it is the constitutionally enshrined right of every citizen to proffer proposals for promoting integrated political and economic development of any part of the country. However, what makes the teeming exercise of this right questionable is the excessive focus on the Igbo question at the expense of more burning issues of national significance such as full-blown terrorism in the North-East, reported mass killings of Nigerian soldiers, the crumbling economy, disappearing fundamental rights and freedoms, child marriages, internal displacements and so forth, most of which are occurring outside the region.”

The irony is that Victoria knows me well and is aware that I have written on all the issues she mentioned. She simply believes I have no right to address the Igbo question; I wonder why? Chidi Odinkalu also wrote a diatribe in which he made false attributions to me creating a straw man that he thrashed, to which I responded.

The most surprising bashing I received, however, was from my good friend Professor Okechukwu Ibeanu, accusing me of a single strand ethnic narrative. Following his energetic promotion of his response to me on the social media, I was inundated by attacks and insults for weeks, mainly by Igbo writers angry that I had insulted them. The problem was that most of them had not read what I wrote; they simply followed what Ibeanu told them I had said. He had written that, “In your Electoral Geography book you tried to attribute specific behavioural attributes to ethno-regional elites. Your book for instance had said that Igbo political elite is preoccupied with seeking money, are kidnappers, etc., basically things to that effect.” It was a very unfortunate statement because he misrepresented the argument in the book. I had edited the book in 2005 with Professor Sam Egwu after extensive consultations in all the geopolitical zones in the country. In the Enugu workshop, stakeholders – civil society, media, political parties and academics – focused on the matter of the moment: the kidnapping of a sitting governor, one Chris Ngige, by a godfather for money. By giving the impression that I was the one accusing Igbos of seeking money and kidnapping, there was no surprise I was subjected to all manners of insults.

The irony is that Ibeanu himself had engaged in his own analysis of the contention between the Igbos and the Nigerian State. The two of us had edited a book in 2009 entitled “Beyond Resource Violence”. In his chapter in the book, Ibeanu had argued, and I quote, that: “The creation of states was designed to alter the Igbo ethnic boundary by encouraging a number of groups, most of them in the Niger Delta, who spoke dialects of the Igbo language to abandon pan-Igbo ethnic identities like Ikwerre, Etche, Ogba and Ndoni. The propaganda of the federal government at the time was to cast these groups as victims of the hegemony of Igbos from the “hinterland”. By so doing, the federal government sought to break the Igbo solidarity and weaken the Biafran secession bid.

“Secondly, state creation was meant to get other ethnic minorities of the Eastern region, such as the Ijaw, Ogoni and Efik to cast their lot with the federal government in the war. This move sought to build on already existing ill feelings towards the Igbo.” Ibeanu concludes this argument on the note that “the decision of Shell-BP to pay royalties to the federal side and not the Biafran side” decided the outcome of the civil war. It is interesting that Ohaeri and Ibeanu believe that they are entitled to analyse Igbo ethnic identity issues, but I am not.

If we are all Biafrans, then we must all have the right to discuss widespread perceptions among virtually all Nigerian groups that they are marginalised and they seek redress in a new Nigeria. Of course ethnicity is not the only issue. Precisely for that reason, in my article on the Igbo Question, I raised issues about the history of the civil war, economic transformation and growing inequality among the Igbo, the sociological fault-line that had developed between the wealthy and disenfranchised youth and partisan political tactics within the zone. To dismiss all these as single-strand narrative simply because it comes from a non-Igbo is not the way to go.

Historically, the fears of domination of one region over the others played a central role in convincing Nigerian politicians of the necessity of a federal solution. The First Republic however operated essentially as equilibrium of regional tyrannies and was characterised by the domination of each region by a majority ethnic group and the repression of regional minorities. The relative autonomy enjoyed by the regions was eroded during three decades of military rule and the creation of states from two regions to thirty-six states, which should have addressed the domination issue. It has not. The steady rise of ethno-regional tensions and conflicts has continued unabated. The reason for this has been the supplanting of the federal tradition with the rise of a Jacobin unitary state. The erosion of multiple poles of political power that have existed in Nigeria by military dictators and subsequently by an all-powerful presidency has exacerbated the spectre of the fear of domination in the country.

The Nigerian state is no longer seen as a neutral arbiter. Negotiation and conflict resolution mechanisms have broken down and ethno-regional political actors have been taking maximalist positions and treating compromise with disdain. Each bloc believes it has the worst deal in the country. It is for this reason that marginalisation, defined, as the outcome of domination, is the most favoured word used by the Nigerian elite to describe their perceived political reality and above all to seek for more access to the national cake.

By examining these narratives, it is possible to show that the same arguments can be made for all groups. I have the right to talk about all Nigerian groups and will continue to do so. Yes Chido, we are all Biafrans and let’s continue to discuss what we think we are.

Muhammad Ali: the Greatest

THE GREATEST, Muhammad Ali transited to the other side on June 4. He was the greatest boxer, indeed sports person of the century; but that was not why he was the greatest. He was one of the greatest poets and entertainers of the century but that was not why he was the greatest. He was one of the most committed advocates for civil rights and racial equality but that was not why he was the greatest.

He was the greatest because he taught oppressed Blacks and all oppressed minorities to develop and articulate their voice on the basis of self-esteem. He showed the world that with voice you could struggle and succeed in rolling back oppression, creating access to opportunities and advancing humanity. RIP Muhammad Ali, the GREATEST for all you did for us, we will continue to use the voice you gave us to continue to struggle to transform oppressed minorities into battle hardened fighters for rights.

* Dr. Jibrin Ibrahim is a Senior Fellow at the Centre for Democracy and Development, Abuja.

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to [email=[email protected]]editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org[/email] or comment online at Pambazuka News.