Bretton Woods institutions’ neoliberal over-reach leaves global governance in the gutter

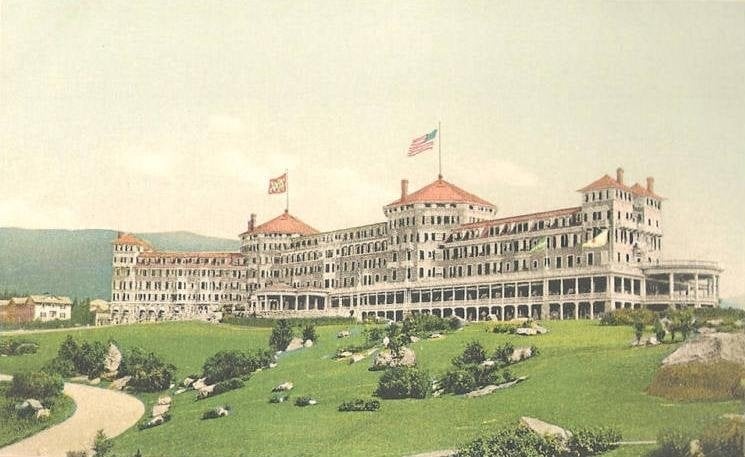

This week, the annual meeting of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund will again be held in Washington, DC, with back-slapping now that the Bretton Woods twins have reached age 75 (they were founded at a New Hampshire hotel in 1944). And with more passion than in recent years, there will be protests, especially climate activists on Friday [18 October] at noon with a strong set of messages, to “end all funding for fossil fuels!”

One voice will be especially loud: Trevor Ngwane’s. A leading activist from Soweto, he was last at a Washington protest in April 2000, amidst 30,000 demonstrators. That week, he co-starred – along with World Bank board chairperson Trevor Manuel – in a documentary, Two Trevors Go to Washington. (Regrettably, young Trevor Noah was still in a Johannesburg high school and not in that particular film; but with his attitude, would have fit in just fine on that picket line.)

The latter Trevor was South Africa’s finance minister from 1996-2009 and in the process, turned the economy into a neoliberal wasteland, as manufacturing fell from 24 to 13 percent of national output and commodity export-dependency rose. On the ground, Manuel’s policies ensured the apartheid era’s world-leading inequality worsened, along with poverty. The main unemployment rate nearly doubled from 16 to 29 percent, and foreign debt soared from US$25 billion to US$70 billion during his reign – and is now US$180 billion. Manuel was always treated with the greatest regard inside the Bank and IMF.

An example of the kinds of dubious deals Manuel and his successor Pravin Gordhan arranged with international financiers was the Medupi coal-fired power plant, which at 4800MW is the largest under construction on earth today. There was widespread corruption on the project by Hitachi – which in 2015 was prosecuted and fined US$19 million under the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act for bribing South Africa’s ruling party– and many other contractors. This was all well known by World Bank President Robert Zoellick, who nevertheless arranged his institution’s largest-ever project loan for Medupi: US$3.75 billion.

But it is a kind of “Odious Debt,” one so awful that Medupi is the reason in late 2017, 16 months before Donald Trump named him World Bank President, David Malpass admitted South Africa was the exemplary case of fraudulent relations with the lender. Correctly, he insulted Bank loan officers while testifying to the US Congress:“They’re often corrupt in their lending practices, and they don’t get the benefit to the actual people in the countries. They get the benefit to the people who fly in on a first-class airplane ticket to give advice to the government officials in the country, that flow of money is large, but not so much the actual benefit to normal people within poor countries.”

This description perfectly fits Medupi and a sister power plant (Kusile), which are driving Eskom’s finances to the brink, due to eight-year production delays, incompetent design and massive cost over-runs, in turn threatening South Africa’s credit-worthiness, as well as security of power supply. (On 16 October, power was turned off in a “Stage 2 load-shedding” disruption due to a broken conveyor belt at Medupi.) Even in their half-built state, the climate implications from CO2 emissions and the consumption of scarce water for cooling the reactors are horrendous.

But merely in financial terms, even leading bourgeois representatives from the Anglo American Corporation’s main think tank now contemplate just shutting the two white-elephant plants and walking away. Progressive writers in South Africa’s main electronic magazines – Kevin Bloom in Daily Maverick and Jonathan Cannard in the Mail&Guardian – argue the Bank should be compelled to face lender liability, and write off the debt.

Instead, refusing to learn, the Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) subsidiary has just made a US$2 million investment in another South African fossil-dependent project: a major new gas terminal on the coast; its partner, Transnet, is one of the most corrupt institutions in Africa. The arrogance is stunning given that the IFC lost its US diplomatic immunity in a Supreme Court case just six months ago.

As local environmental justice, community-feministand anti-povertyactivists contemplate how to punish the World Bank for its proclivity to finance one absurd project after the other, all the while churning out neoliberal research, South Africa appears as a microcosm of what has gone wrong with Bretton Woods pro-corporate neoliberal malgovernance, more generally, these last 75 years.

The multilateral cul-de-sac

Multilateralism has surfed the up-swells and down the troughs of globalisation. In the latter case, the League of Nations faded away during the 1930s as a relevant force for peace, once the waves of Great Depression ripped Western economic interests apart. Today, multilateralism also seems to have entered the final, life-support stage of its 21st century crisis, in part because of the overwhelming power of multinational corporations, and in part because of fast-rising reactionary nationalisms.

As the 2019 G7 summit confirmed, the world cannot contend with the bully-boy ascendance of Donald Trump and other right-wing critics of ‘globalism’ (an anti-Semitic smear), who spew ever more toxic nativist-populist hatred while ignoring their countries’ historic responsibilities to solve problems that their corporations mainly created. As a result, concluded the founder of world-systems theory, the late Immanuel Wallerstein, the 2018 G7 meeting was simply farcical: “Trump may have done us all the favour of destroying this last major remnant of the era of Western domination of the world-system.”

Even at the G20, which is the economic grouping responsible for three quarters of global greenhouse gas emissions and hence the site where addressing climate catastrophe is most urgent, the 2017-19 hosts in Hamburg, Buenos Aires and Osaka were cowed by Trump.

As a result, the world’s most important climate, trade and financial arrangements are increasingly ineffectual and discredited. Notwithstanding a decade-old network of five ‘middle powers’ (better termed ‘sub-imperialists’), the Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa (BRICS) bloc, the South is much less capable of giving the world’s oppressed a chance to make inputs and win long-overdue concessions.

Those expecting progressive change through the BRICS’ collective financial and trade statecraft are disappointed, especially as the world spins out of control economically. “BRICS should be much stronger by now,” one of its founders, former Brazilian president Lula da Silva told Asia Times recently. “I imagined a more aggressive BRICS, more proactive and more creative.”

Instead, global-scale neoliberalism remains dominant. The ill-conceived United Nations (UN) collaboration deal with the plutocratic Davos World Economic Forum in June 2019 followed persistent ‘bluewashing’ concerns about the UN’s discredited Global Compact with some of the world’s least ethical firms, growing corporate manipulation of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, and sabotage of multilateral environmental and human rights governance.

Another sign of ever-worsening degeneracy is personal. Thanks to unashamed cronyism, all the major multilateral economic organisations with the exception of the near-impotent World Trade Organisation (WTO) are run by Westerners: the World Bank and the IMF, the Bank for International Settlements and the UN itself.

The only exception, Brazilian WTO leader Roberto Carvalho de Azevêdo, has notoriously pandered to the West, although to be fair, he is now openly expressing frustration as Trump ratchets up protectionism and as US trade representative Robert Lighthizer obstructs appointments to his crucial Appellate Body. “The dispute resolution mechanism is in crisis,”according to neoliberal Peterson Institute scholars, a paralysis which “runs the risk of returning the world trading system to a power-based free-for-all, allowing big players to act unilaterally and use retaliation to get their way.” That is exactly how Trump and Xi Jinping are handling their trade dispute.

Meanwhile, Bolsonaro is following Trump’s anti-multilateral lead, quickly renouncing ‘special and differential treatment’ provisions for poor and middle-income countries at the WTO – although it is sacred to other BRICS members, especially India. But Brasilia’s divorce began much earlier, complains Third World Network’s Ravi Kanth, because although the developing-country bloc inside the WTO now “exists on paper, it remains paralysed after Azevêdo became director-general in September 2013.”

Bolsonaro also cancelled Brazil’s hosting of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) summit later this year, forcing its move to Chile. Deploying bogus anti-colonial rhetoric, he turned his nose up at the G20’s tokenistic US$20 million grant to control the Amazon’s conflagration. Moreover, Bolsonaro could well wreck the BRICS when he hosts the other four leaders in November.

In any case, the BRICS have already failed miserably when attempting to reform global finance, for example by complaining about – but failing to contest – the IMF and Bank leaders, chosen by Europeans and the US in the 2011, 2012, 2015, 2016 and 2019 ‘elections.’ At the same time, four of the BRICS bought expensive voting-power increases in the IMF (e.g. China rising 37 per cent), but at the expense of countries like Nigeria and Venezuela (which in 2015 both lost 41 per cent of their votes, while even South Africa’s IMF ‘voice’ softened by 21 per cent).

The BRICS’ supposed alternative to the IMF, the Contingent Reserve Arrangement, was founded in 2014 with a notional US$100 billion. It actually gives Washington even more power, by leveraging most of its loans on the condition that the borrower accept an IMF structural adjustment programme. The BRICS New Development Bank’s first five years of lending confirm that it is as rife with corruption, non-consultation, climate damage and inappropriate currency denominations as the World Bank, and even more unfriendly to gender equity.

Likewise, there is no BRICS alternative to Western domination in trade or climate multilateralism. At the WTO, the BRICS were fatally divided, leading to the 2015 destruction of food sovereignty options during the Nairobi summit. And as for climate, the Brazil-South Africa-India-China (BASIC) leaders’ close alignment with Barack Obama at the Copenhagen UNFCCC summit in 2009 held firm through the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement.

But that won’t solve our existential crisis, for the BASIC countries are absolute CO2 emitters at levels even higher than the West (and in South Africa’s case higher per capita than any country in Western Europe). So Paris’ fatal weaknesses suit them fine.

More recently, new causes of global governance illegitimacyappear similar to the centrifugal forces tearing Europe apart. The political commitments of climate-denialist, ‘paleo-conservative’ xenophobes like Trump are different to other Washington philosophies imposed on the world, including the 1980s-90s’ Reagan-Bush-Clinton era of neoliberalism (stretching with Thatcher and Blair into Britain and Kohl and Schroeder into Europe), George W. Bush’s 2000s neo-conservatism and Obama’s 2010s fusion of these two US-centric ideologies.

With just a couple of exceptions (discussed below), an earlier generation of global-scale social-democratic hopes – fostered by serious multilateralists from 1970s traditions, e.g. Willy Brandt and Gro Harlem Brundtland – were dashed by the early 1980s, thanks to the role the Bretton Woods institutions played in fracturing the world’s progressive potentials on behalf of international financiers. The poorest countries went through a ‘lost’ decade or more of austerity. The 1995-2002 middle-income countries’ rolling crises meant local elites allowed the same inappropriate neoliberal regime to be imposed by Washington even more deeply and dangerously in Mexico, East Asia, Russia, South Africa, Brazil, Argentina and Turkey.

Then it was the turn of the West’s ‘labour aristocracy,’ a core group of working-class people dethroned, for they lost their once-solid manufacturing jobs to machines and overseas outsourcing, and were reduced to taking underpaid and under-valued service-based jobs and relying upon fast-degenerating public services. In 2008-09 they too witnessed a replay of brutal 1980s-90s Bretton Woods power plays, once their elites agreed upon a multilateral ‘solution’ to the world financial meltdown: a coordinated central bank bailout for the largest Western financial institutions.

This generosity was confirmed by the 2010s’ official prioritisation – by the IMF, European Central Bank and European Union – of the Frankfurt, New York, London, Paris and Rome bankers’ interests, which were near-fatally exposed to Greece and other peripheral European borrowers. By 2016, neo-fascist political parties were thriving there, while the most resentful within the British and US working classes chose xenophobic backlash in the form of Brexit and Trump.

Self-destructive IMF and World Bank ideology and financing

The crucial break point for multilateral potential was the 1980s world debt crisis, during which neoliberal ideology stretched the Third World so far that the likes of Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere and Cuba’s Fidel Castro even proposed a ‘debtors’ cartel’ – but could not find a sufficient critical mass of other brave leaders even in a Latin America suffering sustained IMF rioting, to the relief of international elites.

At one point in 1983, World Bank President William Clausen quite bluntly explained the balance of forces: “We must ask ourselves: How much pressure can these nations be expected to bear? How far can the poorest peoples be pushed into further reducing their meagre standards of living? How resilient are the political systems and institutions in these countries in the face of steadily worsening conditions?”

Clausen’s power came from the 1979-80 ‘Volcker Shock’: soaring interest rates catalysed by US Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker’s decision to restore the Dollar’s power, in turn causing the Third World Debt Crisis. Clausen and all his successors abused that power to impose the Washington Consensus’s ten policy commandments. The term came from John Williamson of that city’s Institute of International Finance, representing the world’s major banks:

1. Budget deficits … should be small enough to be financed without recourse to the inflation tax.

2. Public expenditure should be redirected from politically sensitive areas that receive more resources than their economic return can justify…

3. Tax reform… so as to broaden the tax base and cut marginal tax rates.

4. Financial liberalisation, involving an ultimate objective of market-determined interest rates.

5. A unified exchange rate at a level sufficiently competitive to induce a rapid growth in non-traditional exports.

6. Quantitative trade restrictions to be rapidly replaced by tariffs, which would be progressively reduced until a uniform low rate of 10 to 20 percent was achieved.

7. Abolition of barriers impeding the entry of foreign direct investment.

8. Privatisation of state enterprises.

9. Abolition of regulations that impede the entry of new firms or restrict competition.

10. The provision of secure property rights...

Needless to say, the victims were mainly women, youth, the elderly and people of colour. The IMF’s flows of annual loans that, thanks to conditionality, locked these policies into place, were initially less than US$15 billion before the Volcker Shock, then soared to US$40 billion by the late 1980s, jumped as high as US$100 billion by the early 2000s, and exceeded US$140 billion by the early 2010s (see Fig 1). The World Bank had similar bursts.

Fig 1. IMF loans, 1970-2015

Source:Reinhart and Trebesch, 2015, p.24.

Added to the neoliberal agenda were trillions worth of ‘illicit financial flows’ manoeuvred into offshore financial centres, leaving governments with rising budget deficits and their social sectors experiencing permanent cost-cutting pressures. IMF economists Jonathan Ostry, Prakash Loungani, and Davide Furceri admitted in 2016 that as a result, “The increase in inequality engendered by financial openness and austerity might itself undercut growth, the very thing that the neoliberal agenda is intent on boosting. There is now strong evidence that inequality can significantly lower both the level and the durability of growth.” But notwithstanding that admission, most subsequent Article IV consultations offered advice that amplified inequality, Oxfam researchers discovered.

The IMF also made a similar confessionabout its role in patriarchy, namely that “some policies recommended by staff… may… exacerbate gender inequality” – but again, when it came to a correction, the IMF “missed the forest for the policy trees,” explains Emma Bürgisser of the Bretton Woods Project. “Almost every macroeconomic policy the IMF regularly prescribes carries harmful gendered impacts, including labour flexibilisation, privatisation, regressive taxation, trade liberalisation and targeting social protection and pensions.”

Activists try to undo destruction

In turn the predatory debt, precarious work and privatisation of so many aspects of life experienced by the world’s citizenries call forth two kinds of responses: appeals to global governance to sort out problems national states have shied away from, and popular revolt. There are both good and bad versions of these top-down and bottom-up responses, as we have seen, with cases such as the Montreal Protocol and Global Fund for AIDS, TB and Malaria as top-down successes, but the latter owes more to bottom-up pressures.

Since the urgency of the situation required a global response, the 1987 Montreal Protocol was supported by even the reactionary Ronald Reagan administration. It committed national states to ensure their corporations (e.g. Dow Chemical and General Electric) stop producing and emitting CFCs within nine years. The ban worked and the problem is receding (aside from recent Chinese corporate cheating on hydro-CFCs).

At present, a Montreal Protocol-type ban on Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions is presumed unthinkable, notwithstanding the impending eco-social catastrophe. A solution as forceful as the Montreal Protocol is needed for GHGs, but the weakness of multilateralism and the pro-corporate balance of forces makes it unlikely within the UNFCCC – unless the world’s rising youth and other climate activists ramp up the civil disobedience and divestment advocacy that is now beginning to worry fossil fuel financiers.

In that spirit, there was one other more recent multilateral solution to a world crisis, AIDS, which shows how to shift the balance of forcesnotthrough elites’ top-down meetings of minds (although within the World Health Organisation and UN AIDS, there were a few bureaucratic allies) – but instead, bottom-up, through militant activism.

Because of groups like South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign (led by visionaries Zackie Achmat and Vuyiseka Dubula), the US AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (‘ActUp’) and the health non-governmental organisations Médecins sans Frontières, a persuasive case emerged in the 1990s – and gained confirmation in 2001 – to exempt copyrighted AIDS medicines within the WTO’s Trade Related Intellectual Property System. Generics were permitted, not made in the US and Germany, but instead in many Southern countries. This resulted in more than a decade’s rise in life expectancy, in South and North alike.

Anti-neoliberal protests help shift the balance of forces, including many millions in the Third World who objected to structural adjustment, or “IMF Riots.” In the main study of these protests, David Seddon and John Walton in 1994 remarked on how not just poor and working-class people, but larger coalitions of society rose up: “Once mass discontent is made evident by these coalitions, political parties may take up the anti-austerity cause in successful bids for national office (e.g. Peru, Dominican Republic). In several countries, austerity protests initiated political crises that sooner (e.g. Sudan, Turkey) or later (e.g. Philippines, Haiti, Poland) toppled the national government.”

Since then, there have been scores more countries – especially in Africa– whose unpatriotic leaders were tossed out of power or drew sustained dissent as they imposed the Bretton Woods institutions’ logic.

Solidarity activism in the North is vital, such as demonstrations at IMF and Bank official events. Major protests included the 1988 Berlin Annual Meetings (which attracted tens of thousands of protestors), the 2000 Spring Meetings in Washington (30,000) and 2000 Prague Annual Meetings (50,000), as well as even the Oslo 2002 Bank research conference on development economics (10,000). One of the main activist challenges to Bretton Woods power was the early 2000s “World Bank bonds boycott” which – at the peak of the global justice movement’s mobilisations – compelled cities as large and financially potent as San Francisco to divest from Bank securities. (Trevor Ngwane and another South African, the poet Dennis Brutus, joined then-US Representative Bernie Sanders to launch the boycott in 2000.)

This led to a ‘fix it or nix it’ debate, in which reforms of the Bank and IMF were so slow that TransNational Institute scholar Susan George fumed in 2000, “These institutions have had their chance. Anytime anyone asks, ‘And what would you put in its place?’ I am tempted to respond, ‘And what would you put in the place of cancer?’” Added Kenyan activist Njoki Njehu, the leading Washington protest organiser at the Bank/Fund Spring Meetings that year, “The IMF and the World Bank increase poverty. The consensus is that the IMF and World Bank cannot be reformed. They have to be abolished.”

It is a debate that needs kick-starting once again. The 75th anniversary is a good time to ask whether such out-dated ideologies and their enforcers deserve to be retired, not (as the right-wing populist protectionists argue) so as to close the door on global governance, but to open it much wider in a way that serves people and planet, not multinational corporate profits. At the same time, by posing the question of abolition, we should also recall instances where impressive reforms were won at the multilateral scale.

*Professor Patrick Bond teaches political economy at Wits University in Johannesburg, South Africa. He can be contacted at [email protected](A version of this article was originally published in Bretton Woods Project Observer, October 2019.)