“The forces of change must come from the global South”

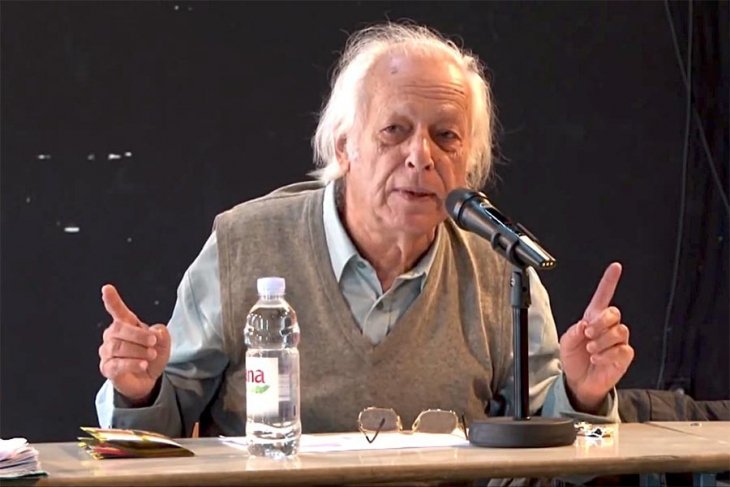

Samir Amin was an economist and intellectual, that has left his marks on academia, as well as on activists.

I have read his Unequal Development (Le développement inégal, 1973) over a summer holiday before I met him in person. Certainly, the world has changed in the 45 years since the book’s first publication, however, to me, many of the assertions still hold true. This book, together with his other numerous publications, has made Samir Amin one of the major proponents of dependency theory, together with other such as André Gunder Frank, Paul Sweezy and Dieter Senghaas.

Many years later, I sit in his office in Dakar, Senegal where he presided over the Third World Forum. He offers me a cigarillo, lighting himself one, and a strong coffee. There was never an option that his office would be non-smoking one. Jokingly, he would sometimes say that smokers have become one of the most persecuted groups worldwide.

While working in Dakar for Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, I had the privilege to meet him every now and then. In these years, he liked to talk quite a bit about the necessity for national sovereign projects in the global South. A national sovereign project is a national movement and policy strategy that follows consequently from his version of dependency theory. The capitalist world economy carries an inherent logic that polarises the centre and the periphery.

While the centre uses the economic resources of the periphery to make economical advances, the periphery is left with an extravert and incoherent economic structure that has no potential to independently develop itself. Without delinking from the centre and defining its own autocentric development strategy, countries in the global South will remain peripheral.

Delinking the economy thus means: actively pursuing an industrial and agricultural policy with a strong role of the state, nationalising key industries and banks and controlling financial transactions and trade. It also means using tariffs and other means of trade policy to gain control over one’s own countries’ economic development. It includes reviving and modernising peasant agriculture. Samir did not invent the term food sovereignty, but it is an essential part of his theory of delinking. In addition, it is the same understanding of sovereignty that feeds his notion of a national sovereign project. Delinking is a selective and not an isolationist strategy.

Pursuing a national sovereign project has a political side to it. To say it with Gramsci: making a hegemonic project out of true national self-determination. Next to the economy, it includes creating an independent media, organising movements and civil society, etc.

Further along our discussion, we both share the preoccupation with the question who are the social forces, e.g. in West Africa, that can define and implement these sovereign projects? He points to the struggles of peasants at the grassroots level against land grabbing, the unrest in Dakar’s suburbs but we end up acknowledging that these have not developed the necessary strength to significantly challenge the fabric of national power. Samir was extremely critical of liberal democracy and the way it dispossesses the popular masses of real decision making. Such form of democracy leaves them with a marginal role of choosing periodically individuals from a limited group, which in turn will run the state according to the needs of the bourgeois classes.

However, according to him, the social forces to change the world must chiefly come from the global South. The privileges of the North and those living there, upheld by the firm grip on key monopolies: like the control of technology and global finance, the access to resources (if need to be secured by force), military capacity and popular media; make it difficult for transformative movements to be radical and mass-based at the same time.

To be non-eurocentric translates into actively addressing the international power relations: the way the ruling classes of the North exert control over the rest of the world. A non-internationalist left in the North is largely counterproductive and more accountable to the vested interest of people of the North to uphold control over the South, than to a real change.

Having challenged Northern political activists again and again on this point is one of the important legacies of Samir Amin.

* Doctor Claus-Dieter König is Senior Advisor, Africa Unit at the Centre for International Dialogue and Cooperation of Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.