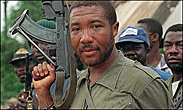

Taylor: the bitterness of war, the sourness of justice

The Charles Taylor trial reportedly cost a whopping $250 million. Was it worth it?

I have been asked by many people about my views on the conviction, on 26 April, of Charles Taylor, Liberia’s former president, for aiding and abetting Sierra Leone’s Revolutionary United Front (RUF). He is the first head of state - after Admiral Doenitz, who very briefly led Germany after Hitler committed suicide, and was convicted by the Nuremburg court after WWII - to be convicted by an international court for war crimes and crimes against humanity. The RUF that Taylor supported waged a nasty bush war against successive Sierra Leonean governments from 1991 to its defeat by a combination of forces, mainly foreign, in 2001. Throughout that war, Taylor mentored the RUF and provided it with weapons and fighters; in turn, the RUF gave him diamonds looted from Sierra Leone’s mines. This is the sum of the judgment against Taylor, and it narrowly reflects the argument that I have been making for over a decade now.

Sierra Leone’s war started in March 1991 when Foday Saybanah Sankoh, a self-adoring former army corporal, led a petty army from territory controlled by Taylor, then an insurgent leader in Liberia, into southern and eastern Sierra Leone. Like Taylor, Sankoh had trained in Libya and, according to the trial judgment, met Taylor there. The judges, however, rejected the prosecution’s overdrawn argument that Taylor and Sankoh ‘made common cause’ in Libya to wage wars in West Africa. The judgment accepted the prosecution’s submission that Taylor facilitated the training of RUF recruits in Liberia and helped launch the RUF’s war, noting that Taylor’s National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) forces ‘actively participated’ in the RUF’s initial invasion in March 1991. (‘Witness to Truth’, Sierra Leone’s Truth and Reconciliation report of 2004, estimated that as many as 1,600 NPFL fighters were involved in the early phase of the Sierra Leonean war, or about 80 per cent of the RUF forces. This grew to 2,000 within a few months of the invasion.)

However, striking a balance between the prosecution’s claim that Taylor ‘effective controlled’ and led the RUF at this point, and Taylor’s claim that only former NPFL members joined Sankoh and that he had nothing to do with the RUF after the Sierra Leone invasion, the judgment delicately noted that the prosecution did not prove beyond reasonable doubt that Sankoh took orders from Taylor - or that Taylor participated in the planning of the invasion.

This point was always a difficult legal one, not least because the trial was not about the crime of aggression (which had not even been defined by the time Taylor faced the court). The indictment period did not even cover the origins of the war - the temporal jurisdiction of the court is from November 1996 to the official end of the war in 2002. Compounding this problem was the fact that the most credible person that would have definitively testified to this would have been Sankoh, but he died long before Taylor faced the court. In fact, it is a testimony to the tenacity and industry of the prosecution that it was able to sufficiently prove even the crime of aiding and abetting, since Taylor had effectively eliminated key witnesses to that crime. He allegedly had Sam Bockarie, his key link to Sankoh and the RUF during the period of the indictment, murdered in Liberia shortly after Bockarie was indicted. Johnny Paul Koroma, a notorious Sierra Leonean coup maker who also dealt intimately with Taylor, simply disappeared: he was also allegedly murdered either in Liberia or Ivory Coast on Taylor’s orders after his indictment. These events must count as the most comprehensive and effective evidence-tampering in an international war crimes trial ever.

I have always thought that the prosecution’s invocation of the notion of ‘joint criminal enterprise’ (JCE) was ill-advised, and successive judgments by the court rubbished the concept. This concept was first used by the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia (1991-1999). It considers each member of an organised group individually responsible for crimes committed by that group within the ‘common plan or purpose’. The Appeals Chamber of the ICTY decided on 21 May 2003 that ‘insofar as a participant shares the purpose of the joint criminal enterprise (as he or she must do) as opposed to merely knowing about it, he or she cannot be regarded as a mere aider and abettor to the crime which is contemplated.’

The concept was roundly rejected by the court in the trial of the leaders of the admirable Civil Defence Forces (CDF), since ‘the evidence led by the Prosecution in this case to show a joint criminal enterprise [is"> insufficient to prove its existence against those named persons beyond reasonable doubt.’ Conviction around the concept was entered only in the case of the leaders of the RUF, and even here the judgment involving the pathetic and roguish Augustine Gbao was problematic, looking very much like guilt by association. Though the prosecution did not establish Gbao’s direct involvement in crimes during the war, the judges concluded that because he was the RUF’s ‘ideological trainer’, Gbao ‘significantly contributed to the [Joint Criminal Enterprise">, as the leadership of the RUF relied on the RUF ideology to ensure and to enforce the discipline and obedience of its forces to the RUF hierarchy and its orders, this being a factor which contributed to the furtherance of the Joint Criminal Enterprise.’ Justice Shireen Fisher dissented, noting that Gbao’s conviction ‘abandons the keystone of JCE liability as it exists in customary international law.’ Gbao was nevertheless given a global sentence of 20 years and flown to jail in Rwanda. Many observers feared that the same approach would be used to convict Taylor.

The prosecution had argued that Taylor had made a ‘common cause’ with Sankoh to invade Sierra Leone and loot is diamond reserves, and that the RUF’s terror campaign was a direct result of this blood pact. Taylor’s Defence made no effort to deny Taylor’s support for the RUF, but it stated that ‘diamonds only financed the procurement of arms and ammunition’ for the RUF between 1998 and 2001. The Defence denied that diamonds were the reasons why Taylor supported the RUF, stating in the Final Brief what no one has challenged: that the RUF diamond mining began ‘post the invasion’ which happened in March 1991. It stated: ‘There is no evidence of any discussions relating to diamonds pre the Sierra Leonean invasion to suggest that the invasion might have been motivated by a desire to pillage Sierra Leone’s diamonds.’ The point was that the Defence’s key argument was not that Taylor did not support the RUF, but that he did not do so either as part of JCE or with ‘an underlying intention to cause terror’. The Defence contends that there was a ‘purely political motive’ for Taylor’s support of the RUF war, which may be immoral but certainly not illegal in international law (since the law of aggression was not at issue).

The judgment on 26 April broadly agrees with this, dismissing the notion of JCE as it involved Taylor’s role. But while the judgment agreed with Taylor that he and Sankoh had ‘a common interest in fighting common enemies’ - the Liberian anti-Taylor insurgent group ULIMO and the Sierra Leonean government supporting ULIMO - this is actually tangential to the case, since the period (1991-1992) falls outside the temporal jurisdiction of the court.

Of profound importance to many people in Sierra Leone and elsewhere is the finding involving Taylor’s role in the events surrounding the Johnny Paul Koroma coup in 1997, and in particular the resurgence of rebel forces leading to the devastating attacks on Freetown in January 1999. Close to 6,000 people were killed, including hundreds of Nigerian peace-enforcement troops, and the hands of dozens of people were crudely amputated by the rebel forces during those attacks. The judges established Taylor’s direct role in instigating the attacks on diamond areas of Kono as well as the subsequent attack on Freetown. Here the judgment uses the word ‘instructed’ to describe Taylor’s orders to Johnny Paul Koroma and Sam Bockarie. With his eyes ever on diamonds, Taylor ‘emphasised’ to Bockarie that taking over Kono was more important than attacking Freetown at that point. He also told Bockarie to make the attack ‘fearful’. As a result, the demented Bockarie, who called himself Maskita, announced ‘Operation No Living Thing’, with predictable results. More crucially, the judgment establishes that Taylor arranged ‘a large shipment of arms and ammunition from Burkina Faso’ to the rebels in Makeni; these arms were instrumental in the attacks on Kono and later Freetown. It is important to note that the UN Panel of Experts on Liberia had established in 2000 that the arms were supplied by Victor Bout, recently convicted on unrelated charges in the US, and that they were presumably paid for by diamonds from the RUF in Sierra Leone.

It is of interest that a number of names appearing in the judgment as playing a facilitating role in this sordid and murderous business were neither indicted by the court nor even invited as witnesses: Gaddafi, Ibrahim Bah, and, of course, Blaise Campaore (who as president of Burkina Faso surely knew and supported it all).

Also of interest has been the unenthusiastic - sometimes even hostile - reaction of a good number of Liberians to the conviction of their former president. This is partly because Taylor was not charged with his many crimes in Liberia but for his role in supporting a foreign war. But there are quite a few Liberians who actually do not think that Taylor should have been held accountable for his crimes at all, local or international. This reflects a deep-rooted culture of impunity in the country. I lived in Liberia for nearly two years during its truth and reconciliation process, and attended dozens of testimonies there. Many of these, by former commanders in Taylor’s NPFL, proudly narrated how they participated in attacks inside Sierra Leone, and how they were fully supported by Taylor to do so. None of them to my knowledge expressed remorse about what they did - but then none of them, with the quirky exception of General Butt Naked, apologised to Liberians for the atrocities they committed in Liberia itself.

Was it all necessary, this expensive and long trial? I think that the proceedings were unnecessarily prolonged by overpaid judges and lawyers, and I think that the court erred very badly in indicting and convicting the leaders of the CDF. The Taylor trial alone reportedly cost $250 million, nearly six times more than the total revenue officially generated by Liberia in 2003 ($44.2 million), the year that Taylor was forced to relinquish power. Still, I think that the conviction of Taylor - as nasty a gangster as ever become president in Africa - is a signal event, something we should all celebrate in our region. As I write this, I remember the day that Taylor was helicoptered into the Special Court compound in Freetown. I stood among the small crowd of people there that evening. A woman in the crowd turned to me after Taylor was sent to his cell and said, apropos of a statement made by Taylor in 1990, ‘Well, he told us that we in Sierra Leone will taste the bitterness of war. We did. But now he will taste the sourness of justice.’ The sourness of justice: that indeed is a lovely phrase there.

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* The writer is author of 'A Dirty War in West Africa: The RUF and the Destruction of Sierra Leone' (London, 2005).

* Please send comments to editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org or comment online at Pambazuka News.