African labour and social militancy, Marxist framing and revolutionary movement-building

It is a great period to be a revolutionary activist in Africa. Yet the sense of stop-start progress and regress in so many sites of struggle reflects in part how poorly the working-class, poor, progressive middle class, social movements and other democrats have made alliances. The African uprising against neoliberalism hasn’t yet generated a firm ideology. In this case the best strategy would be a critical yet non-dogmatic engagment with the various emerging forces on the left.

This year is the 100th anniversary of the Bolshevik’s victory in Russia. It set the standard, at least initially (before Joseph Stalin took over in the mid-1920s), for a party of workers and other oppressed people capturing state power. At least briefly, it confirmed the potential for shop-floor and grassroots base-building even within a repressive national regime (the Czar), then a jumping of scale to participation in an intermediate semi-democratic state (the Mensheviks), and then national economic control and massive international influence.

Crucially, the 1917 events in Russia were guided at the critical moment by a revolutionary party, which reaped the whirlwind because it had a clear ideology, a vanguard of advanced cadres and steely leadership (especially Lenin and Trotsky) able to grasp the opportunities. The vast masses of unorganised peasants, the small half-hearted middle class and the army and police did not prevent the proletariat’s victory, notwithstanding being outnumbered and immature compared to the huge working classes elsewhere in Europe.

After its rapid degeneration, the Soviet Union’s errors were explained as due either to a democracy deficit and stifling bureaucracy (as a chastened former defender, SA Communist Party leader Joe Slovo argued in 1990) or (as Pallo Jordan famously rebutted a month later) to the “class character of the Soviet model” which crushed workers’ and society’s self-emancipation. The gaping difference in those narratives endures today.

Meanwhile, contemporary power exercised by shopfloor and grassroots activists in Africa is typically under-rated. There are various ways to measure this power, including police statistics,[2] journalistic accounts and business executive surveys. For example, the world’s protest activity is recorded in the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (GDELT), initiated by George Washington University’s Center for Cyber and Homeland Security, drawing upon millions of media reports. Latest data from November 2016 (not typical because of Donald Trump’s election and India’s currency controversy) show Africa well represented: hot spots included Tunisia, Libya, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia and South Africa.

Meanwhile, contemporary power exercised by shopfloor and grassroots activists in Africa is typically under-rated. There are various ways to measure this power, including police statistics,[2] journalistic accounts and business executive surveys. For example, the world’s protest activity is recorded in the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (GDELT), initiated by George Washington University’s Center for Cyber and Homeland Security, drawing upon millions of media reports. Latest data from November 2016 (not typical because of Donald Trump’s election and India’s currency controversy) show Africa well represented: hot spots included Tunisia, Libya, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia and South Africa.

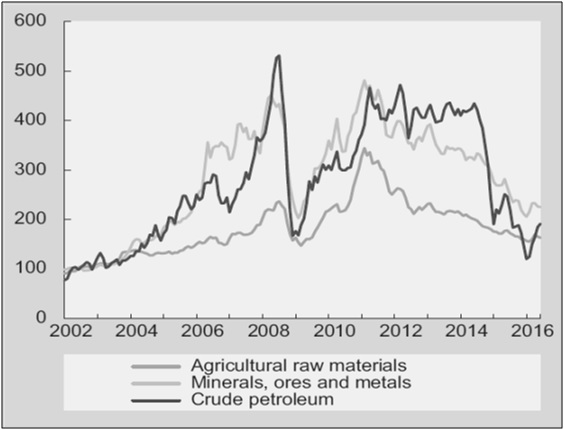

Additional sources of ‘Big Data’ on social unrest include the US military’s Minerva programme, which has a project – Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (Acled) – tracking Africa’s violent riots and protests. Compared to 2011, when North African (‘Arab Spring’) protests reflected a dramatic increase on prior years, many more protests across Africa were recorded five years later. While 2016 appeared to have slightly fewer than 2015, there is no question that in most places on the continent, the rate of protesting was far higher than at the peak of the commodity super-cycle in 2011.

Another dataset – based on subjective impressions not objective event reports – is the World Economic Forum (WEF) annual survey of 14 000 business executives in 138 countries that informs its Global Competitiveness Report.[2] One survey question relates to labour-employee relations, and whether these are “generally confrontational or generally cooperative” on a scale of 1-7. In the 2016-17 report, the WEF found the most cooperative labour movements were in Norway, Switzerland, Singapore, Denmark and Sweden (scoring above 6.1).

The least cooperative was, for the fourth year in a row, the South African proletariat (with 2.5). Other African countries with very militant workforces are Chad (3.5), Tunisia (3.6), Liberia (3.7), Mozambique (3.7), Morocco (3.7), Lesotho (3.7), Ethiopia (3.8), Tanzania (3.8), Algeria (3.8), Burundi (3.8), and Zimbabwe (4.0). These dozen were in the top 30 countries in terms of labour militancy. The most placid African workforces were found in Rwanda (5.3) at 18th most cooperative, Mauritius (4.8) and Uganda (4.6). In general, African workers are the least cooperative of any aggregated in the world’s continents.

At a time mainstream observers have memed, “Africa Rising!”, surely a better term is that Africans are uprising against Africa Rising mythology. This uprising is by no means a revolutionary situation, nor even a sustained rebellion. One of the main reasons is the failure of protesters to become a movement, one with a coherent ideology to face the problems of their times with the stamina and insight required.

Frantz Fanon himself complained in Toward the African Revolution, “For my part the deeper I enter into the cultures and the political circles, the surer I am that the great danger that threatens Africa is the absence of ideology.” Amilcar Cabral agreed: “The ideological deficiency within the national liberation movements, not to say the total lack of ideology – reflecting as this does an ignorance of the historical reality which these movements claim to transform – makes for one of the greatest weaknesses in our struggle against imperialism, if not the greatest weakness of all.”

Was Numsa’s insurgency just a ‘moment’ – or a future movement?

Within South Africa, the largest union – with 330 000 members confirmed at its December 2016 congress – remains the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (Numsa).[3] What many observers have remarked upon – often critically (e.g. most writers in this week’s Pambazuka News) – is Numsa’s intense rhetorical militancy, in the wake of its bruising battle with labour nationalists and Communists affiliated to the African National Congress (ANC), as well as with “Middle Class Marxists.”

To put the fierce exchanges between various fractions of the South African Marxist left into context, consider some recent history. Although there are many targets of its ire ranging from white monopoly capital to the independent left intelligentsia, Numsa’s most decisive war has been with former comrades in the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) and its intellectual guide, the SA Communist Party (SACP), which began in earnest during the last Numsa congress, in December 2013. My own overwhelming impression from that event was how 1400 delegates (mostly shop-stewards) drove the union rapidly leftwards, to the point of formally calling for President Jacob Zuma to resign.

It was an extraordinary U-turn, given Numsa’s strong support for Zuma to replace President Thabo Mbeki in 2006-08. Like many in the Cosatu-SACP circuit, the expectation was that in exchange for that support, Numsa would benefit from a radical leftward turn in macro-economic policy and much greater state subsidies to improve working people’s livelihoods.

As some of us grimly predicted, however, Zuma dutifully stuck with the neo-liberal project and inevitably broke working-class and Communist hearts. Inevitably, anti-Zuma grumbling reached the point of active protest. And so it is not surprising to hear Zuma’s desperation ‘talk left’ gimmicks, such as last November in Pietermaritzburg when he described the BRICS as an apparent distracting tactic: “It is a small group but very powerful. [The West] did not like BRICS. China is going to be number one economy leader… [Western countries] want to dismantle this BRICS. We have had seven votes of no confidence in South Africa. In Brazil, the president was removed.” (The following week in Parliament, Zuma was asked during the president’s Question Time by an opposition legislator: “Which Western countries were you referring to? How did they plan on dismantling BRICS? And what will the effect of their actions be on our economic diplomacy with these Western countries over the next decade?” Zuma replied, according to the Hansard, “I’ve forgotten the names of these countries. [Laughter.] How can he think I’m going to remember here? He he he he.”)

My sense in December 2013 was that a key reason for Numsa’s revolt against the Alliance was the still-strong memory of the August 2012 Marikana massacre of 34 platinum mineworkers who demanded a living wage of $1520/month. Numsa delegates were literally stunned into silence when they viewed Rehad Desai’s film “Miners Shot Down,” which later won the Emmy Award for Best International Documentary.

The seeds of this radicalisation were sewn when Irvin Jim became leader in 2008. Like any good union, Numsa has had to direct enormous resources into the bread-and-butter activities of member support that any force in organised labour must promote before doing serious politics. While there are always setbacks along these lines, Numsa has nevertheless made remarkable steps away from labour corporatism – the Alliance that has served workers so poorly since 1994 – and towards independent militancy. Since 2008, Numsa leaders and cadres have:

- restored the internal Numsa left’s strength (after the union’s self-destructive Mbekite era under Silumko Nondwangu’s leadership);

- pushed forceful new arguments into the public sphere about the character of the ANC neoliberal bloc’s long-term (transMandela-Mbeki-Zuma) class betrayal;

- helped identify where SACP and Cosatu forces were most weak in defending the ANC, and thereby opened a healthy debate culminating in the 2013 Numsa special congress where the first call to toss out Zuma was made;

- survived what many feared might be a serious (and KwaZulu-Natal-centric ethnicist) challenge by former Numsa president Cedric Gina’s new metalworkers’ union;

- won a five-week national metals strike in 2014 and coped with massive deindustrialisation pressures ever since, as the prices of aluminium and steel hit rock bottom and as dumping became a fatal threat to the main smelters;

- built up membership to today’s 330 000;

- pushed the political contradictions to break-point within Cosatu by 2015, resulting in not just Numsa’s expulsion but also the firing of the extremely popular general secretary, Zwelinzima Vavi, who leaned too far left for other Cosatu leaders’ comfort;

- put members on the street in fairly big numbers (e.g. around 30 000 protesting corruption just over a year ago, in spite of a clumsy breakdown in alliances with other groups in the more liberal reaches of civil society);

- maintained member – and broader proletarian – discontent with the class character of specific rulers, including Zuma, Ramaphosa, Gordhan and Patel (even though the latter two were at the 2016 congress unsuccessfully attempting to sweet-talk Numsa), so as not to be co-opted into playing a role (again) in the 2017 ANC electoral congress’ internecine battles (as is Cosatu on behalf of Ramaphosa);

- knit together Cosatu dissidents into a rough bloc (at peak having nine unions) and then set up a process for the announcement (May 2016) and launch (sometime this year) of a new workers’ federation; and

- quite realistically opened the door for a new workers’ party (and this is just a partial list.)

The latter two soon-to-be accomplishments – a new federation under the leadership of Vavi and a potential workers party – are the main projects on the horizon. The United Front project rose briefly in 2013-14 and then crashed by 2016 (for important reasons that this article cannot properly integrate), alienating many logical allies and losing respected staff in the process, as well.

And although Vavi represents a broad, open-minded socialist current that spans from NDR to radical civil society, Numsa has recently emphasised a definition of its own particular ‘line’ regarding a National Democratic Revolution. That line, with its category of a “Marxist-Leninist trade union” prior to a vanguardist workers’ party, is dismissed as “rigid Marxism-Leninism!” by independent-left intellectuals, to which Numsa ideologues reply: “useless petit-bourgeois radical-chic parasites!” or words to that effect. This is the extent to which certain ships are passing in the South African night.

But if we are frank, Numsa has a massive vessel plowing through choppy waves above deep, torturous currents in unchartered waters, and the left intelligentsia occupies a dinghy limited to well-known shallows. (The latter site is where someone like me typically splashes, as conditions haven’t matured yet in South Africa to play anything much more than what becomes a substitutionist or worse, ventriloquist function, instead of what can be termed a properly “scholactivist” role.)

However, what if by the time of the 2019 election the Numsa vanguard finds a way to run alongside (parallel) or in direct coalition (or even merger) with the country’s main leftist party, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF)? Recall that after its formation in 2013, the EFF went from 6% of the vote in the 2014 election to 8% of the vote in the municipal poll of 2016, enough to throw the ANC out of the Johannesburg and Pretoria city councils, as the EFF coalesced with the centre-right Democratic Alliance. (This unhappy marriage could result in divorce before 2019, probably amidst EFF and ANC contestation over an inevitable upturn in township ‘service delivery’ protests.)

With the ANC down from its 2004 high of 69% in a national election to its 2016 low of 54% in the municipal poll, it is quite conceivable that in narrow electoral terms, enormous potential exists for a left party to play a decisive role in national politics, as did the EFF in Johannesburg and Pretoria municipalities. However, if the self-declared Marxist-Leninist leaders of both Numsa and the EFF ever find each other in coalition, could what is termed the ‘Numsa moment’ become a Numsa-EFF movement?

This scenario is not looked on favourably by many on the independent left, because of a general concern that EFF leader Julius Malema – whose record of ANC patronage in Limpopo Province still chills leftist spines – will take the EFF’s 10+% voting share in 2019 back into the ANC in the event that (as in August 2016 in Joburg and Tshwane) he becomes a kingmaker. This scenario assumes the ANC vote falls below 50% and that all opposition parties gang up to deny the ruling party any further national spoils. Malema told an audience last year that if such an opportunity arises in 2019, he might first destroy the ANC then rebuild it in alliance with the EFF. But if it is either Cyril Ramaphosa, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma or Zweli Mkhize running the ANC, that hijack won’t be easy to sustain.

In such a scenario, the antidote would be a workers’ party ally or influence on the EFF, to prevent regeneration of neoliberal nationalism with new elites. This is what some in Numsa would argue is their historical role, once the petit-bourgeois radicalism of the EFF peaks and retreats into populism – a stance for which I hope they will be proved wrong. But we really have no way to judge ahead of 2019 given the unpredictable character of left politics in South Africa. If matters were more predictable, I’ll conclude, the conditions for much stronger movement building – a “United Resistance” of left forces, as it’s now being termed in the United States against Trump fascism – would have already generated a bottom-up communism, instead of the residual Capital-C Communism that still dominates in so many terrains of real politik.

The deep roots and fragile surface of South African communism

To illustrate the conundrum – and by way of further vital context – think too what it means to have fought these battles first and foremost, as did key Numsa leaders, in the Eastern Cape Communist Party tradition. Bearing that in mind, the M-L rhetoric makes sense, because it appears to be the case that:

- the SACP-within-the-ANC is in its dying days (with continual rumours of Party leaders in the Cabinet suffering a forthcoming purge, and with the youth putting walk-out pressure on the party bosses), and

- Cosatu’s failures on nearly all policy and political fronts could take several important member unions to the brink not only of demanding that Zuma be replaced as president (he probably won’t be before 2019) but also of breaking the Alliance within a year or so.

If these are the most proximate political processes looming, then the Numsa rhetoric might be seen not as M-L dogmatism, but instead as careful positioning to capture a great many cadres who are now finally giving up on the ANC. (Some Numsa shopstewards already moved into the EFF in the last election.) The Numsa political push into the hearts and minds of a prestigious liberation movement is something that in Zimbabwe was tried – and that failed – in the case of the Movement for Democratic Change, which also began as a workers’ party (in January 1999 at the Chitungwiza Working People’s Convention) but quickly moved to the right. To pull at the ANC from the left using its own NDR language may well be successful, as an alternative to the political alienation faced by so many working-class activists whose mass political experience is grounded in traditional loyalty to the ANC.

Numsa’s historic role, in my view, is to continually remind a huge ANC NDR-supporting constituency that there is a logical explanation for SACP-Cosatu failures within the Alliance: namely, that the Party and labour leaders became fat-cats indistinguishable from the bosses. (This is a fate some observers accuse Numsa leaders of reproducing, too, with the ‘social distance’ between leadership and workers still vast, just as is the distance between Numsa workers – many of whom have struggled hard for five-digit monthly salaries – and the poorest South Africans.) So the Numsa rhetoric is quite clear. Its simple message is that the NDR and two-stage revolution were correct as conceptualisation and strategy, but that the wrong people were given the task of implementation, because the ANC, Cosatu and SACP together grew far too comfortable maintaining the neoliberal nationalist status quo.

Now, that line of argument may not readily appeal to most Pambazuka readers considering these sentences, fair enough. Still, bear in mind that the NDR tune remains especially appealing to those who still consider the ANC’s pre-1994 populist nationalism to be South Africa’s most prestigious political project. Even though we are nearly 23 years past ‘liberation,’ this tradition retains deep roots. And it is likely that, with its new leadership (probably either Dlamini-Zuma or Ramaphosa), the ANC can continue to maintain its 50%+ majority in the next election and beyond.

So while some readers may have big problems in principle and theory with the NDR argument and the sell-out thesis, still, it is hard to dispute in empirical terms. The ‘first stage’ – the ‘political kingdom’ – was substantively reached in 1994. A ‘second stage’ – economic justice – is long overdue. And the persuasiveness of the SA comprador class – ranging across the main intra-ANC divide (i.e., from the Zuma-Gupta ‘Zupta’ patronage machine to the neoliberal Treasury bloc) – represents the main barrier to the revolution’s second stage.

With South Africa in a profound state of crisis, it is tragic that in spite of Numsa and EFF efforts as well as SACP-Cosatu anti-capitalist rhetoric, only two narratives dominate the political space: first, Zupta and second, neoliberal good-governance. Hence, breaking through with tried and tested NDR-speak might well work, and leaders like Malema, Jim and Vavi certainly know their constituencies far better than I do.

To address the left intelligentsia, have those middle-class Marxists (like me) made profound errors that could distract Numsa from gathering its strength? Of course. Every initiative by South Africa’s far left has failed to attract working-class membership, much less leadership. Unlike the North African cases in 2011, the mix of that intelligentsia, progressive NGOs, social movements, frustrated citizens and creative labour activists in South Africa have not found anything like the mass support of EFF and Numsa.

It may not be the 2019 election, but in South Africa there will be a point when looking beyond the rhetorical battleground and the immediate cadre-gathering becomes far more important than the current conjuncture. At a time much closer to a crunch moment, when alliances are really vital to make, might the masses from Numsa workplaces take to the streets in combination – not contradiction – with the left movements’ regroupment trajectory?

After all, what an excellent period to be an activist (or like me, an armchair academic) promoting justice in South Africa:

- Numsa hasn’t folded to repression and divide-and-conquer and still holds up the strongest class challenge to capitalist power; the Food and Allied Workers Union walked away from Cosatu, and the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union wasn’t beat back into oblivion during the 2014-16 mining crisis;

- the working class as a whole is still considered the world’s most militant at a time SA inequality has soared and the capitalist class is considered (by PricewaterhouseCoopers) to be the world’s most corrupt;

- the EFF have grown stronger and less politically erratic;

- the new terrain of Gauteng urban politics (where EFF and ANC will likely compete to support – if not catalyse – community protests) will get very interesting as contradictions continue to emerge;

- communities continue protesting at very high rates over service non-delivery or excessive pricing or politicians’ arrogance, notwithstanding the state’s ever-stronger repressive and surveillance techniques;

- although student movement momentum recently faltered after a spectacular 2015 national debut, they have lots more potential for future mobilisations and alliances; and

- social movements, the Right2Know coalition, women, LGBTI activists, Equal Education, Treatment Action Campaign and other protesters make their voices heard and often win important battles along the way.

For 2017, can the infrastructure supporting all of this (even including support structures inhabited by obscure academics and others reading this) expand at the rate needed, so as to move forward as quickly as reality will demand?

Conclusion: a whirlwind to catch

The African uprisings since 2011 have taught progressives that in the pro-democracy and social justice scenarios of mass demonstrations that made several countries so fertile for a change of state power – Gambia (2017), Burkina Faso (2014), Senegal (2012) and Tunisia (2011), for example – the moment of change comes without warning. There is typically a build-up in social grievances and an explosion. The aftermath includes a profound threat of counter-revolution, which in Burkina Faso was repelled in 2015, but which in Egypt and Libya have been successful in suppressing democratic, progressive social movements since 2011 (in both cases with Western imperial aid and arms to the counter-revolution).

Will South Africa find itself, as Moeletsi Mbeki predicted, facing “Tunisia Day” – a kind of joyous (yet threatening to elites) uprising such as January 2011 – as early as 2020? Can Africans update the threat, to encompass the extraordinary advances that have become evident in post-dictator regimes, or in sites like South Africa itself where the overthrow of (Moeletsi’s brother) Thabo Mbeki’s AIDS-denialist policies in 2004 raised life expectancy from 52 to 62 thanks to nearly four million people getting medicines for free?

The sense of stop-start progress and regress in so many sites, including South Africa, reflects in part how poorly the working-class, poor, progressive middle class, social movements and other democrats have made alliances. The Africans uprising against the neoliberal Africa Rising strategy of export- and resource-dependency, hasn’t yet generated a firm ideology. Such an ideology was much more apparent when in the 1960s-70s the phrase “self-reliance” accompanied much leftist discourse. The Lagos Plan of Action even reflected this ideological approach.

It may be that an eco-socialism associated with Ubuntu philosophy and deglobalising economies will emerge. It may be that some uniquely South African version of the Marxist-Leninist framing will come from Numsa. Nothing can be readily predicted in the current conjuncture. The only strategy it seems to me worth following is a non-dogmatic appreciation of the various forces, so that whatever principles, analysis, strategies, tactics and alliances that do emerge on the left can be treated with both respect and comradely critique.

The debate over Numsa may not yet have arrived at that healthier stage of inquiry, but at least there is a debate and an inquiry – the first steps to reclaiming some sort of profound ideological breakthrough so that the pessimism of the Fanon and Cabral warnings becomes a genuine Afro-optimism worthy of the ongoing struggles by so many African activists.

* Patrick Bond is Professor of Political Economy, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

End notes

[1] These are often unreliable, as regularly demonstrated by University of Johannesburg researchers Jane Duncan, Peter Alexander, Carin Runcimann and Trevor Ngwane.

[2] This is “the longest-running and most extensive survey of its kind, capturing the opinions of business leaders around the world on a broad range of topics for which statistics are unreliable, outdated, or non-existent for many countries.” Although Africa is the continent with least coverage, at least several dozen executives were surveyed in 34 countries, with Rwanda’s survey pool of 120 the highest in Africa (the US had 485 executives surveyed), and Gabon’s 33 was the lowest in Africa and internationally. Of interest to us, the specific question each year is “In your country, how do you characterize labor-employer relations? 1 = generally confrontational; 7 = generally cooperative.”

[3] Disclosure: I attended the Numsa congress as an occasional volunteer to the union in the “Friends of Numsa” category so the next pages are written with at least some sort of bias, albeit with no role in crafting the M-L language discussed below.