The conspiracy of Katangese nationalism

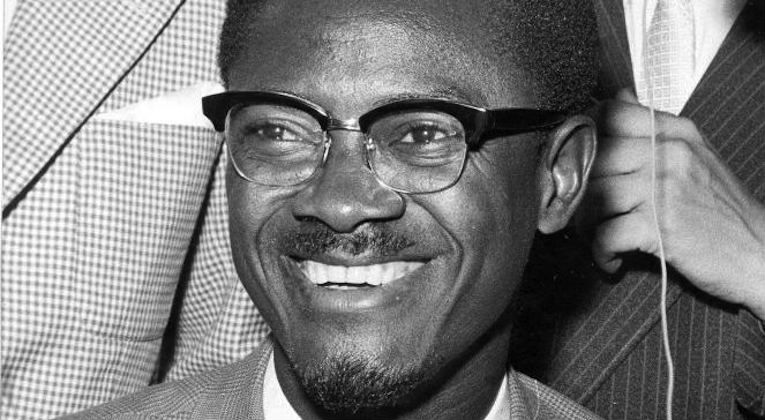

Having failed to prevent Patrice Lumumba from taking power in Congo, a cabal of European and American politicians and businessmen saw the maintenance of indirect white rule in Katanga as the only means of ensuring their continued profiteering from Congo’s huge mineral wealth. Perpetuating a façade of African nationalism the white lobby supported autocrat Tshombe to plot for secession.

From the early days of the Congo Crisis in 1960, an extensive group of businessmen and politicians across Europe, the United States and white-dominated southern Africa conspired to play African nationalism against African nationalism.

The collapse of governance in the former Belgian Congo following independence was a flashpoint built upon the unfounded fear of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba’s radicalism and anti-West policies. Such a turn of events provided a window of opportunity for the southern, mineral-rich state of Katanga to secede under the guise of ethnic nationalism or tribalism.

The reality, however, was that an international Katanga Lobby had essentially accentuated a fringe nationalist movement to revive the combined Bayeke and Lunda empires from the aspirations of their “lackey” or “stooge”, Moïse Tshombe.

While the newly-formed, secessionist State of Katanga had ostensibly self-determined motives, the region was in actual fact dominated by what historian Matthew Hughes describes as “a shadowy group of businessmen and politicians keen to keep control of the wealth they derived from white rule in Africa.”

Preparations of a lobby

Having failed to prevent Patrice Lumumba taking power in the inaugural Congolese elections, those that were to constitute the Katanga Lobby saw the maintenance of indirect white rule in Katanga as the only means of ensuring their continued profiteering from what was the bulk of the Congo’s mineral wealth.

Even before the country’s independence, a secret delegation of European settlers in Katanga had visited Rhodesian leader Sir Roy Welensky to propose Katanga’s entrance into his Central African Federation, “should certain political developments [take] place.”

Welensky even proposed various loose associations between his newly-formed Central African Federation, Portuguese Angola and Mozambique, apartheid South Africa, and the Belgian community in Katanga. Though these plans were never realised, the combination of monetary and ideological appeal provided a common goal for those who wished to continue the white dominance of Katanga.

The infant state of Congolese multiparty politics and the haste in which the elections were conducted led to the political climate being dominated by pre-existing tribal and/or ethnic cultural organisations, most notably President Joseph Kasavubu’s Abako party and Moïse Tshombe’s Conakat party.

Tshombe, having squandered his family’s fortunes, had long been openly groomed by Belgian settlers’ organisations including the Union for the Colonization of Katanga and the Federation of settlers in the Belgian Congo and Ruanda-Urundi.

Tshombe was the son-in-law of deposed Lunda Paramount Chief Mwata Yamo III, and his second-in command and future Katangese Interior Minister Godeforid Munungo was the grandson of formidable Bayeke Chief Msiri.

Together, they sought to represent those considered “true Katangans” (i.e. members of Katanga’s indigenous tribes) through a mixture of tribalist and regionalist (and eventually autonomist) policies. Belgian settlers meanwhile campaigned for their legitimacy under the comparable slogan “Katanga for Katangans”.

Tshombe’s ambitions coincided with those of international investors, Belgian settlers, white mercenaries, and American and British conservatives who viewed him as the first and only black champion of colonial interests, or in the words of historian David N. Gibbs, an “African Uncle Tom”. Highly corruptible and perpetually indebted to foreign creditors, Tshombe and his long-groomed party were seen ripe for the picking by what was henceforth known as the Katanga Lobby.

Katanga independence day

On July 11, 1960, under the auspice of the widespread military revolt against Lumumba’s central government, Tshombe declared Katanga’s independence.

This was not necessarily the will of the people of Katanga, as the Conakat Party had only achieved a plurality in the local assembly (although Belgium did remedy this by allowing it to rule outright). The idea of secession was also not articulated as a policy of the party prior to the election. Nor had the general public at all been consulted after the election.

Instead, it was the small Belgian community in Katanga that had long called for independence. The Union for Colonisation, which became the supposedly more subtly-named Union for the Collaboration of the Middle Class, served to organise the Belgian settlers into a single organisation. Its leader, a vocal white supremacist, served as an advisor to Tshombe. During the conflict, it became the Katangese Union until finally dropping a title altogether but retaining their cohesiveness, serving as Tshombe’s military leaders in the periodic absence of sufficient mercenaries.

To justify and legitimise the region’s secession, a facade of African nationalism was perpetuated by the white community. Katanga crosses (cast copper crosses used as currency in the region in the 19th and 20th centuries) adorned the flag, coat of arms, coins and air force roundel.

The organisation of the newly-proclaimed State of Katanga was essentially that of a European-dominated police state. Upon independence, Godeforid Munungo, who also served as head of the secret police, apprehended the entire parliamentary opposition. While total imprisonment statistics are unknown, it is known that 950 people were released from incarceration in June 1961.

Belgian officials held almost all other key civilian and security posts, while the few remaining African officials were inexperienced and nevertheless appointed Belgian advisors. This situation led the UN to describe Belgian influence in Katanga as “omnipresent”.

One UN document even read that “the idea that Katangan resistance is a native and African affair is a myth put out for foreign consumption and is scoffed at in private by the Europeans here.”

A peculiar alliance

Following Katanga’s unilateral declaration of independence, the Katanga Lobby played the all-important role of financing and controlling Tshombe, recruiting military assistance and mercenaries, and garnering diplomatic support.

In an unprecedented backflip, white supremacists seemed unable to suppress their newfound fondness of Tshombe, with Sir Roy Welensky beginning to ‘wine and dine’ him. Welensky also encouraged British politicians such as Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and Foreign Secretary Lord Home to support Tshombe, even having the audacity to ask whether they had fallen for the alleged Afro-Asian excuse that Tshombe was a puppet, as well as publishing propaganda pamphlets for distribution in Britain.

Portuguese dictator Antonio Salazaar, under whom Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, and São Tomé and Príncipe had remained integral territory of the metropole, and who viewed natives of the aforementioned areas as “slightly darker Portuguese” rather than African, also began to tout the virtues of Katangese independence.

Welensky facilitated the recruitment of European mercenaries in Southern Rhodesia, as had occurred in South Africa. Both he and Salazaar also shipped arms to said mercenaries, and accommodated them in Northern Rhodesia and Angola, respectively, to launch and retreat from military incursions.

Welensky’s government went so far as to smuggle seven Fouga Magister jets from Europe on behalf of Tshombe, while Salazaar donated several warplanes to be used by the mercenaries.

The corporate octopus

Corporate participation in the Katanga Lobby was merely self-advocacy by those businesses that had long exploited Katanga’s resources under colonial rule.

In 1899, Cecil Rhodes established Tanganyika Concessions Ltd. (or Tanks, for short) to stake out a share of mineral rights in the region. The Belgian Comité Spécial du Katanga agreed to share the Katangese mineral wealth 60-40 through the jointly-run Union Minière du Haut-Katanga in 1906. The committee itself was two-thirds controlled by the colonial administration, with the remaining share consisting of private investors.

The Union Minière eventually expanded to encompass several subsidiaries, of which the following operated in Katanga: Metalkat (operator of coal and zinc mines), Sogelec (electricity provider), Sogechim (chemical processor), Sogefor (agriculture), and the African Metals Corporation (handling trade with the United States).

The Comité Spécial also oversaw a number of other mining operations, including Géomines (exclusive holder of tin mining rights in northern Katanga), Cotongo (cotton growing and processing company which made use of slave labour under the unabashed moniker of “prestation agriculture”), and Bécéka (the dominant railway operator in Katanga), as well as its two subsidiaries: Copagnie du Congo pour le Commerce et l’industrie (promotion of industry and commerce) and Profrigo.

Backing the consortium alongside Rhodes’ British South Africa Company, the monopolist of the Northern Rhodesian copper belt of which Tanks was an offshoot, was the Belgian investment bank and insurance provider, the Société Générale. The Société had controlled almost 70% of business in the Congo leading up to independence, after which it dissolved the Comité Spécial.

This prevented the independent Congolese government from inheriting its colonial predecessor’s stake and in turn profiting from the mineral wealth. The culmination of companies also meant that every aspect of Katangese industry and development was controlled by a small group of foreign businessmen.

Furthermore, this foreign monopoly of Katangese industry was compounded by isolation when infrastructure elsewhere in the Congo had collapsed, as electricity had to be generated from Rhodesian coal and minerals had to be exported via the Luso-British Benguela Railway which ran through Angola.

This complex web of white-owned and run companies was actually less complex behind the scenes.

The intersecting directorates of these operations in the midst of the Katangese secession exemplify the way in which a small group of European businessmen essentially controlled Katanga behind the facade of the Tshombe government.

The Société Générale, which backed the Union Minière through the Comité Spécial (and later directly), shared three of its directors with Tanks. Meanwhile, the Union Minière itself shared six of its directors with the Société Générale and seven with Tanks.

Notably, Belgian industrialists Edgar Van der Straesen and Herman Robiliart served as directors for all three. Robiliart in particular had long voiced concerns to his colleagues as well as the Belgian government regarding the economic devastation he anticipated should Patrice Lumumba be elected.

The Anglo-Belgian partnership that was the Union Minière also saw directors, auditors, reports, shares, and dividends shared between those two countries. It also saw a confluence of business and politics, with Conservative politicians such as Lords Selborne, Clitheroe, Robins, Salisbury, and Sir Ulick Alexander representing the Katanga Lobby. They were led by Captain Charles Waterhouse, who served as a director for both the Union Minière and Tanks during the conflict.

These politicians belonged to a small number of MPs who garnered sympathy for their cause amongst the ranks of the Conservative Party. Their achievements included convincing Prime Minister Macmillan to cancel shipments of bombs to the United Nations peacekeeping forces in Katanga, as well as eventually achieving a general ambivalence towards the UN campaign against Katanga.

The Lobby also saw the participation of other multinationals which did not have large interests in Katanga, but were encouraged by the promise of a free hand in a white-dominated state.

Unilever, for example, had been granted large swaths of land in the former Belgian Congo for palm oil plantations. Despite these concessions being granted mostly outside of Katanga, the company nevertheless positioned its financial might behind the Katanga Lobby.

Similarly, Shell Oil, which was the second-largest distributor of oil in the Congo and a partner in an oil pipeline project with Socopetrol, itself a part of the Petrofina group and thereby linked to the Société Générale, lent support to the lobby. The director of the American Consulate in Katanga, Lewis Hoffacker, who had erred on the side of the Katanga Lobby and introduced Tshombe to the vocally-supportive Senator Thomas Dodd, later became an international affairs consultant at Shell.

Buying muscle

Upon succession, these enterprises paid taxes that were owed to the Congolese Central Bank to the Katangese Treasury instead, thereby financing the secessionist state’s independence. Their revenues were used to purchase weapons, equipment and ammunition, and recruit mercenaries and advisors on behalf of Tshombe (the Union Minière alone accounted for over 50% of the Congo’s monetary output).

One mercenary recruiter, known only as Mr. Bogard, was a former employee of the Union Minière, while another, Marcel Hambursen, was a Belgian industrialist wanted by French authorities.

The recruited mercenaries, alongside Belgian settler employees of the mining concerns, formed a white gendarmerie which became the backbone of the Katangese succession following the withdrawal of Belgian troops due to pressure from the United Nations.

Following further pressure from the UN, Katanga agreed to expel its mercenaries until Belgium slowed the process by replacing UN oversight with its own Consular Corps, which merely sought their voluntary evacuation. This delay saw the expulsion process reversed following a personal bid of support from Welensky, after which Katangese forces were instructed to turn against both UN troops as well as black Katangans who were sympathetic towards the central Congolese government.

Their campaign alone saw the mercenaries force over 25,000 Katangans to seek UN protection in the Katangese capital of Elizabethville (now Lubumbashi). The mercenaries also embarked on a campaign to recapture the infrastructure and property of companies based in Katanga which had come under the control of UN or central government troops. In their expedition into northern Katanga to regain control of the mines, processing plants and railways owned by Géomines, the mercenaries burnt several Baluba villages to the ground in order to rid the area of any hostile forces.

Katanga Lobby in America

In American conservative circles, the hitherto unknown Lumumba was hastily misequated with communism, while the more familiar Tshombe shone as a beacon of free enterprise. Two prominent groups in favour of Katangese independence were conservative advocacy organisation, the John Birch Society, and youth activist organisation Young Americans for Freedom.

Leading the Katanga Lobby in Washington, D.C., was Michel Struelens, a Belgian who served as director of economic affairs in colonial Katanga before claiming to be Tshombe’s personal representative as head of the Katanga Information Service (KIS) on Fifth Avenue, New York City. As a lobbyist Struelens tirelessly advocated for the plight of Katangans, who he claimed suffered from atrocities committed by the United Nations in their struggle for self-determination.

Struelens was funded by Belgian mining concerns, so much so that the Information Service’s monthly expenditures regularly exceeded $100,000. Much of these funds were spent on hiring public relations firms and taking out a large number of full-page advertisements campaigning in support for Katangans, “a brave people that seeks only the right to have a voice in deciding its own destiny.” He became so influential in the United States that he even worked on behalf of the US State Department for a brief period before the two found their goals at odds.

The KIS also founded an activist group in December 1961, the American Committee for Aid to Katangan Freedom Fighters, which received public support from right-wing ideologues such as William F. Buckley, Jr., John Dos Passos, and Republican Senator Barry Goldwater.

The group was headed by African-American activist Max Yergan, a former communist who had toured the Belgian Congo in the 1950s only to praise the colonial administration upon return. Much of their rhetoric emphasised the alleged multiracial harmony, anti-communism and relative order to be found in Katanga, rather than the economic benefits motivating their financial backers.

Another prominent leader of the Katanga Lobby’s US activities was publicist and conservative activist Marvin Liebman, of China Lobby fame. Staunchly anti-communist, Liebman promoted the Katangese secession as being the best example of an independent state in Africa.

A prominent political voice was found in Democratic Senator Thomas Dodd from Connecticut, another staunch anti-communist who also lauded Ian Smith’s Rhodesia and apartheid South Africa. During his time on the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Dodd was both in close contact with Belgian business circles and recipient of “a large monthly stipend” from Tshombe himself.

The State Department’s congressional liaison described Dodd’s views as representative of Belgium, dismissing them as “strictly business,” while historian David N. Gibbs concluded that his views were “virtually indistinguishable from those of Union Minière.”

Although the group’s lobbying did contribute to Kennedy’s pressuring of the UN to negotiate rather than militarily defeat Katanga as well as a general weakening of its opposition towards the breakaway state, it had no substantial impact on US foreign policy.

Nevertheless, it did cause waves in the Republican Party, with several pro-Katanga articles being published in official literature and prominent figures such as Richard Nixon and Herbert Hoover endorsing the cause.

It should be noted that some Republicans and Southern Democrats did support Katanga but not in conjunction with the Katanga Lobby, as the conflict was instead used as a pivotal foreign policy issue from which to mobilise voters and as a substitute for supporting the civil rights movement, respectively.

Falling flat?

Despite collective wide reach and political prominence of the Katanga Lobby, no state officially recognised Katanga’s purported sovereignty. Early (and illegal) Belgian paratrooper deployments in Katanga were merely carried out under the guise of protecting the Belgian settler community. This is not to say the Lobby's goals were not indirectly achieved.

Later financial and political support for Katanga even lacked excuses akin to the Hamitic hypothesis as had been used Ruanda-Urundi to politically favour Tutsis. Secret diplomatic cables instead recommended that “all self-respecting states not lower themselves” to such an extent.

Meanwhile, Belgian politicians continued to publicly commend the “superhuman virtues” of the “splendid people” of Katanga. Nevertheless, Belgium remained, as described by The Economist at the time, “one big Katanga lobby”.

Neither Portugal, South Africa, nor any other like-minded administration recognised Katanga’s sovereignty. A delegation of intermediaries allegedly sent on behalf of Tshombe did try to bribe the government of Costa Rica with $850,000, however this was immediately refused, with one official replying, “Why do you choose Costa Rica, a small country, a democratic country, to propose this dirty matter? Why don’t you try a dictatorship?”

When the secession had failed, Rhodesian forces helped Belgian settlers flee Katanga. Meanwhile, Tshombe was also escorted out by Rhodesian forces, bringing with them the Katangese gold reserves.

Though the parting of Katanga was unsuccessful, the damage had been done. The literal conspiracy of the Katanga Lobby determined the course of international relations between the West and newly-independent Africa for years to come.

In 1962, then-Assistant Professor in Anthropology and Sociology Alvin W. Wolf concluded in Liberation that “every African political leader who tries to free his people from the political and economic bondage in which they are now held will be portrayed in the United States as a ‘Moscow-trained Marxist’, while the monopolistic business structure of that part of Africa will be portrayed as a model of free enterprise. War may start in Berlin or in Laos; it can hardly be avoided in Africa.”

* Zac Crellin is a journalism and international studies student from Sydney, Australia.

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR/S AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a [url=http://www.pambazuka.org/en/friends.php] Friend of Pambazuka[/url] and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to [email=[email protected]]editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org[/email] or comment online at [url=http://www.pambazuka.org/]Pambazuka News[/url].