BRICS states and capital surveil their societies: anti-imperialist or sub-imperialist?

When it comes to control of the populace, what are the imperialist, anti-imperialist or sub-imperialist characteristics of the BRICS network of countries: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa? Can the BRICS deliver progressive outcomes – as some of its proponents claim – or not?

I am interested in this question from a surveillance and intelligence perspective. In the wake of Edward Snowden’s disclosures about mass surveillance abuses by at least five intelligence agencies, can the BRICS offer a genuinely different path to the surveillance state and society path that many countries in the global North appear to be on?

It is noteworthy that when at least one BRICS country – Brazil – attempted to steer a different path a few years ago, its efforts often did not find favour with other BRICS states.

Consider the United Nations (UN) resolution to establish a Special Rapporteur on Privacy. It was spearheaded by Brazil and Germany, which had become targets of Washington’s National Security Agency surveillance. South Africa failed to support this move.

South Africa, China and Russia also voted for a substantial watering down of a UN Resolution on the protection and promotion of human rights on the Internet, South Africa ostensibly because it did not want to appear to be a United States lackey.

This sentiment was captured by the former South African ambassador to the UN Dumisani Kumalo, when the country was exiting the UN Security Council: “We didn’t do things the way the British and the Americans wanted us to do them and if you don’t do it like the big ones, the French and the Americans and the British, the way they want to do them, then you are a cheeky African. Well I am happy being a cheeky African.”

So, on Internet freedom and online privacy matters, it is both telling and disturbing that South Africa has chosen to side with China and Russia, and their outright authoritarian agendas on surveillance matters, rather than Brazil, which had at least tried.

South Africa also appeared to have adopted wholesale the intelligence doctrine critical of the “colour revolution”, associated most closely with Russia’s dismissal of mass protest. This term has its origins in the former Soviet Union and Balkans, and refers to pro-democracy movements in these regions from the early 2000’s onwards, with significant involvement of students and non-governmental organisations. The protests adopted particular colours or flowers to represent their struggles.

The doctrine critical of these protests was developed by targeted governments – including Russia – to explain them and why they spread. The basic assumption is that protests spread because Northern countries with imperialist agendas sponsored them, and not because of a “demonstration effect” in which ordinary citizens gained confidence from other courageous demonstrators.

At the 7th BRICS meeting of High Representatives for Security Issues, South Africa’s State Security Minister David Mahlobo said, “In Africa we have, as intelligence and security services, observed the importance of non-governmental organisations in Africa’s development and poverty alleviation programmes. We however remain concerned that the nefarious activities of rogue NGOs [non-governmental organisations] contribute to Africa’s persistent insecurity. We note that rogue NGOs are not only a threat to the national security of our respective states but they also threaten our collective security as a continent and have the potential to derail the African Union vision of a conflict-free Africa.”

Mahlobo continued, “We oppose external forces in seeking regime change or colour revolution. We are, therefore, supportive of BRICS’ initiatives geared towards opposing and countering external interference, even if it is indirectly carried out through rogue NGOs. In this regard, we concur with the need to strengthen cooperation on NGO management, including improving laws and regulations, upgrading the management level and improving the oversight mechanisms.”

In the case of the protests and broader movements for social change in South Africa, painting these struggles as being motivated by illegitimate “regime change”, allowed the ruling African National Congress (ANC) to portray them as being subversive; in other words, they have an express or implied intention of committing crimes against a democratically-elected state. It is not difficult to understand the attractiveness of the “colour revolution” doctrine for the ANC, as the party can blame internal instability on imperialist manipulation, rather than on the unequal social relations.

Regimes that were targeted by the protests adopted similar repertoires of colour revolution prevention strategies (or “anti-colour insurance” strategies), after a process of authoritarian learning.

These regimes could respond by using at least one of five strategies: isolation (where the regime insulates itself from the protest movement), marginalisation (where the regime pushes the movement out of the political mainstream), distribution (where the regime distributes rents unevenly to benefit some movements and disadvantage others), repression (where the regime contains the movement using force or threats of force) or persuasion (where the regime attempts to reason with the movement to persuade it to change its course of action).

Clearly, Mahlobo’s intention was to deal with rising mass protests and NGO support for them, through isolation and marginalisation, with elements of repression thrown in where these strategies didn’t work.

South Africa has also proved to be very open for business when it comes to the technologies that could be used for data exploitation and surveillance purposes. Smart cities present BRICS communications companies with massive markets for their wares, with a company like the Chinese Hauwei offering municipalities “smart cities in a box”.

Smart cities have become controversial for commodifying digital spaces, exploiting citizens’ data without their consent, reinforcing spatial inequalities and undermining their “informational right to the city”.

According to Edwin Diender, Vice President, Government and Public Utility Sector, Huawei Enterprise Business Group: “Europe is almost over-regulated, making it very difficult to proceed swiftly, compared to South Africa,” says Diender. “In fact, if Amsterdam and Johannesburg were to compete in implementing a particular smart solution, I believe Johannesburg could easily win the race.”

Johannesburg and Cape Town have signalled their intentions to become smart cities, in spite of the fact that the country’s data protection law, the Protection of Personal Information Act, is not fully in force yet, and in a grindingly slow process, the privacy/ information regulator is still in the process of being established. The roll-out of smart technologies is running far ahead of the policy. So, right now there is nothing to prevent Huawei from cashing on in this practically unregulated market for peoples’ data.

Unless data protection measures are implemented fast, China’s present could well become South Africa’s future. Consider China’s use of facial recognition technology, which is becoming so ubiquitous for authoritarian purposes that it is even being used to publicly identify, name and shame jaywalkers.

As facial recognition and other smart technologies such as Automatic Number Plate Recognition become more prevalent on our streets, we will be less and less able to move around anonymously. These technologies can be (and have been) used to track and identify people leaving protests, for instance.

South Africa doesn’t want to buck the surveillance trend because it too has aspirations to become, not just a net importer of surveillance technologies, but an exporter, too. So it has an industrial interest in not wanting to play the surveillance game differently.

Like Israel, it is becoming a middle player in the surveillance industry, by commercialising security skills honed in their respective military-industrial complexes and honing security products for export. Already, the equipment of South African company Vastech has turned up in places like a Muammar Gaddafi’s listening room in Libya.

Thus rather than playing an anti-imperialist role, increasingly South Africa is playing a sub-imperialist role, mouthing anti-imperialist rhetoric, while itself engaging in and benefiting from the very imperialist surveillance practices it has criticised the West for.

So, it is small wonder that it has aligned itself the most consistently with those other BRICS countries that are most likely to display sub-imperial tendencies, namely China and Russia.

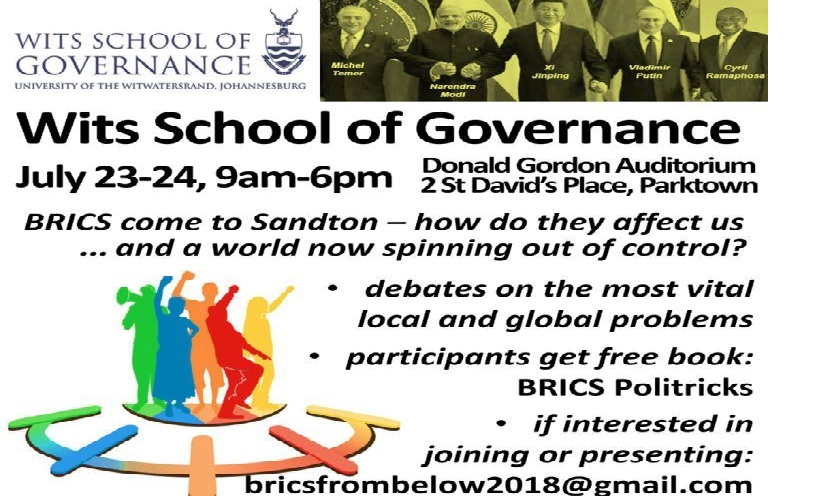

* Jane Duncan is professor at the University of Johannesburg; this is a transcript of her lecture at the brics-from-below Teach In at the University of the Witwatersrand, 23-24 July 2018