Reflections on the 60th anniversary of the convening of the first AAPC conference in Accra

After more than six decades since the gathering of the first All-African People’s Conference (AAPC) in Accra, Ghana on 8-13 December 1958, renewal of revolutionary Pan-Africanism is needed on the continent and globally.

At that time Ghana was the fountainhead of Pan-Africanism where the previous year the Convention People’s Party (CPP) and its founder Kwame Nkrumah won independence from British colonialism.

Immediately after the declaration of liberation, Nkrumah proclaimed in his inaugural speech on 6 March 1957 that the independence of Ghana “is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total independence of the African continent”. Later in mid-April 1958 the first Conference of Independent African States (CIAS) was held in Accra with eight liberated governments in attendance.

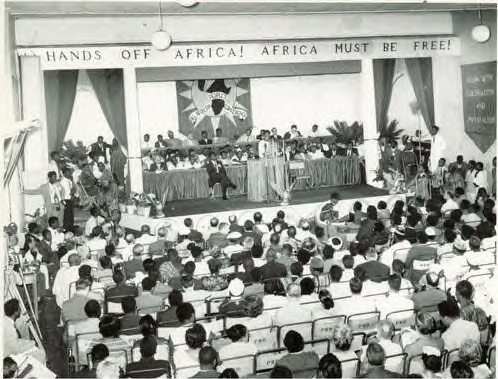

Nonetheless, the AAPC was much different in character than the CIAS. There were approximately 300 delegates in attendance representing 65 different national liberation movements, trade unions and mass organisations from 28 countries.

At the time there were nine independent African states and all of them sent representatives to the AAPC with the exception of Sudan, which had just undergone a military coup on 17 November. Leading members of the anti-racist movement in apartheid Union of South Africa were not present either since many were ensnarled in the racist legal system, which had indicted over 150 Congress movement organisers for treason in 1956.

The African National Congress (ANC) had three official delegates at the conference, one of whom was from the United States. Writers Ezekiel Mphahlele and Alfred Hutchinson were the other ANC representatives while Rev. Guthrie Michael Scott was there from Southwest Africa (later Namibia).

These delegates even from independent states came to Accra not as envoys of their governments. They were present representing their political parties, labour organisations and mass struggles.

All African People's Conference American Committee on Africa delegation, Dec. 1958.

Delegations travelled to Ghana for the AAPC from Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria, which was in the throes of an armed struggle against French imperialism led by the National Liberation Front (FLN). There were also leaders from Somalia, Uganda, Tanganyika and Zanzibar. The British colonies of Nyasaland (later Malawi), Northern and Southern Rhodesia (today Zambia and Zimbabwe), had significant representation.

Others from the Cameroons, divided between French and British colonialists, along with Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Senegal, Ivory Coast, Togoland were present in large numbers. The language barriers between French and British outposts seemed to be overcome through translations and bi-lingual delegates illustrating the genuine pan-African character of the conference.

George Padmore, a long-time Communist and Pan-Africanist writer and organiser from the Caribbean nation of Trinidad, served as the principle convener of the AAPC. During this period Padmore was Nkrumah’s chief advisor on African affairs while he resided in Ghana.

All African People's Conference Chair Tom Mboya with Kenya delegation, Dec. 1958

Kenyan trade union organiser Tom Mboya chaired the five-day conference. Other notables were Patrice Lumumba of the newly-created Congolese National Movement and Frantz Fanon of Martinique representing the Algerian FLN.

Official observers attended from the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China where messages of solidarity were sent by leaders Chou en-Lai and Nikita Khrushchev. The official position of the AAPC was non-alignment and positive neutrality in regard to international affairs. However, the US and other western states were severely criticised for their colonialist and imperialist policies.

The AAPC had a large multi-racial observer-delegation from the US, which included Congressman Charles Diggs, Jr. of Detroit; Mary-Louise Hooper, a wealthy heiress and campaigner for civil rights and the struggle against apartheid, who represented the ANC in Accra; Marguerite Cartwright, a prominent African American sociologist and journalist whose columns appeared regularly in various publications including the Pittsburgh Courier and Amsterdam News of New York; Claude A. Barnett, the founder of the Associated Negro Press, which publicised events in colonial and post-colonial Africa for decades; Etta Moten-Barnett, a well-known actress-artist and the wife of Claude A. Barnett; Eslanda Robeson, an anthropologist and writer who was a co-founder of the Council on African Affairs and the wife of African American artist and actor Paul Robeson; Shirley Graham-Du Bois, a composer, writer and leading member of the US Communist Party, who read an extensive address penned by her husband; among others.

This gathering was a milestone in the Pan-African struggle being the first international gathering on the continent, which brought together various parties and non-governmental forces to map out a strategy for the total liberation of Africa. Nkrumah in his concluding address called for the formation of a United States of Africa.

Pan-Africanism and national liberation

Of course the movement towards liberation and equality among African people was accelerating by the late 1950s in various parts of the continent and the diaspora. The AAPC would hold two additional summits: in Tunis in January 1960 and Cairo in March 1961.

On 4 June 1962, Nkrumah and the CPP hosted the Nationalist Conference of African Freedom Fighters in Accra. The Ghanaian leader’s address to the 1962 meeting identified imperialism as the main enemy of African people fighting for their liberation.

By early 1963 there were over 30 independent African states on the continent. On the 25th of May the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) was formed in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia that established a Liberation Committee designed to provide material aid to those still fighting to overthrow colonialism.

However, Nkrumah at the founding OAU Summit distributed his classic work entitled Africa Must Unitewhere he dedicated an entire chapter to the political economy of neo-colonialism, the mechanism utilised to continue western imperialist domination over the land, resources, waterways and people of the continent.

Just two years later (1965), Nkrumah published Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism,where the US capitalist system was exposed for its role as being the major impediment to genuine African liberation and unity. Nkrumah and the CPP were committed to building a socialist Ghana and Africa, noting this was a prerequisite to the unity, which is necessary for the region to move beyond neo-colonialism.

Nevertheless, the anti-imperialist states in Africa constituted a minority surrounded by pro-western client governments, which were weak and fragile. The internal class and political contradictions in Ghana during the mid-1960s opened the way for the US administration of the-then President Lyndon B. Johnson to engineer the overthrow of Nkrumah while he was out of the country on a mission to end the Vietnam War. When Nkrumah arrived in Peking, People’s Republic of China on 24 February 1966, he was informed by Premier Chou en-Lai that the CPP had been toppled by lower-ranking military officers and police.

Nkrumah soon resettled in Guinea-Conakry where the-then President Ahmed Sekou Toure declared the Ghanaian leader as co-president. Nkrumah remained in Guinea where he wrote prolifically on the emerging armed phase of the African Revolution and the burgeoning class struggle. By 1971 he was sent to Romania for medical treatment where he died on 27 April 1972.

Revolutionary Pan-African renewal needed for the 21st century

Even with the transformation of the OAU to the African Union (AU) in 2002, the continent remains underdeveloped and fragmented. Many of the programmes advocated by Nkrumah at the AAPC and the first three summits of the OAU (1963-1965) have been adopted, the most recent of which is the creation of an African Continental Free Trade Area on 21 March 2018 in Rwanda. However, these measures absent of a coordinated socialist revolutionary programme for the strengthening of the working class, farmers and youth will not result in a United Africa based upon the interests of the majority.

Military intervention by the US and other North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) countries is continuing to render the continent defenceless in the face of growing imperialist intrigue designed to facilitate the exploitation of the natural wealth and labour of the people. The coup against Nkrumah was part and parcel of a series of manoeuvres to prevent the economic and consequent politically independent existence of Africa.

The destruction of Libya by the Pentagon and NATO in 2011 illustrates the mortal dangers of the US Africa Command (AFRICOM). Libya, the most advanced country in Africa under the former martyred leader Col. Muammar Gaddafi, is continuing as a major source of instability and reaction where Africans are sold into human bondage, often facing death in the Mediterranean Sea while seeking an elusive “better life” in Europe, further institutionalising the theft of national sovereign wealth, which has rendered the North African state destitute.

Pentagon bombs are being dropped on a weekly basis in the Horn of Africa nation of Somalia while AFRICOM military bases are utilised as spring boards to carry out the genocidal war against neighbouring Yemen, a Washington-led war that utilises Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to carry out the imperialist biddings of Wall Street and the White House.

Pan-Africanism in the 21st century must be built from the ranks of the proletariat and the popular stratums of the continent. The stability and defence of Africa will be secured when the masses take control of the resources and labour of the people, guaranteeing socialism on a regional scale.

*Abayomi Azikiwe is Editor at Pan-African News Wire

*Note: AAPC Video Clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zbE1VhvmXeg