In the 2014-2016 Commission of Inquiry into the circumstances that led to his death, evidence was produced that showed that the device that exploded in his lap, and which was constructed by Guyana Defence Force army sergeant Gregory Smith, was remotely controlled from a range of frequen

Wazir Mohamed

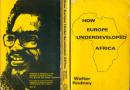

Tagged under Pan-Africanism Other Walter Rodney

Tagged under Pan-Africanism Other Walter Rodney

[This paper was delivered at the forum on October 12, 2016 specially organized by the University of the West Indies at Cave Hill Barbados under the theme: “Reflections on the Commission of Inquiry into the death of Walter Rodney: What next?”]

Tagged under Pan-AfricanismMany concerned citizens from all parts of the world have come together to form the Justice for Walter Rodney Committee.

Tagged under ResourcesAs I write, the war – which originally was supposed to take one week – is now in its second week, with no end in sight. This new war with weapons fired from remote locations and from military aircraft continues on military convoys and command and control locations in Libya.

Tagged under Global SouthAs all of us, and as the international community continues to give understandable solidarity to the self-proclaimed revolutionaries of Libya, it is also important that we give equal weight the condemnation of reported atrocities now surfacing against dark-skinned people (Black Africans) by the re

Tagged under Governance Libya Tagged under ICT, Media & Security

Tagged under ICT, Media & Security

June 13, 2010 will mark 30 years since Walter Rodney ‘the prophet of self-emancipation’ was murdered in Guyana at the hands of a brutal dictator acting in cahoots with the agents of international capital.

Tagged under Governance- Tagged under Governance Zimbabwe

- Tagged under Governance

- Tagged under ICT, Media & Security

Pagination

- Page 1

- Next page