Delayed minimum wage lets down South Africa’s working poor

An insightful analysis on the current debates in South Africa to have a national minimum wage and its implication to the wider working class.

Heated political debates and ideological contestations abound in South Africa on the establishment of a national minimum wage, which can be reduced to a Goldilocks analogy. In one bed are those that are claiming that the proposed minimum of R20 (US $1.60) an hour is too much and would lead to economic hardship for businesses and job losses. In another bed are those who are insulted that a minimum of R20 an hour is being proposed as it is below a living wage and are incensed that this will erode wage gains in organised sectors.

In the third bed are those who are claiming that R20 an hour is just right, a place to start, to test the impact of a national minimum wage on the economy and jobs which it can be built on, to address wage differentials and uplift the working poor. Just like Goldilocks, this hasn’t gone well for millions of workers who would have earned more from 1 May 2018 had it come into effect as planned. Whilst cabinet has approved the minimum wage bill, parliament must still deliberate and pass the bill before it can come into effect.

So what would have been the outcome for workers if the bill had gone through? The truth is that it is difficult to say with certainty. Figures that were used in national dialogues to determine the proposals on the national minimum wage are from 2014 employment statistics, using monthly earnings based on 2016 prices. These figures are being used in arguments made today. While not as accurate as the figures could be, they give a sense of the potential number of workers whose earnings could improve from the proposed national minimum wage.

A monthly wage based on the R20 minimum would be about R3500 (US $280). 6.2 million, or 47 percent of all workers, earn below R3500, but not all stand to benefit if the minimum wage is implemented. But there are separate proposed minimum wage rates for agricultural and domestic workers and those in public employment programmes, so, reducing the potential number that would benefit from the proposed R20 an hour minimum wage to under four million workers, which is about 30 percent of all workers. The impact would be across a number of sectors: one fifth of workers in mining and quarrying and electricity and water supply; more than a third of workers in manufacturing, transport, communications and financial services and half of workers in wholesale and retail trade and construction who are earning less than R3500, would potentially be entitled to higher wages.

Farm workers’ minimum wage is proposed at R18 (US $1.45) an hour, about R3100 a month for those in full time employment. Minimum wage for domestic workers is proposed at R15 an hour or roughly R2600 a month for full time workers. In 2014, 80 percent of all agricultural workers earned less than R3000 a month and 80 percent of all domestic workers earn less than R2500 a month. Thus majority of workers in these sectors potentially stand to gain from the increased minimum wage rate.

Expansion of employment in the public sector has been one of the biggest drivers of employment since 2004 through the government’s Expanded Public Works programme and makes up the majority of jobs in the community social and personal services (CSP) sector. CSP is by far the largest sector in terms of employment, accounting for 22.5 percent of total formal employment in 2014. If formal and informal CSP workers are counted, this totals 3.2 million workers in 2014, of which 1.1 million workers earned below R3500 a month; forming the largest share, nearly 20 percent, of workers who earn less than R3500 in the economy.

CSP workers will not benefit from the new minimum, as many in the sector are public employment programme workers, for whom the wage proposal sets an hourly minimum wage of R11 (US $0.90), at less than R1900 (US $153) a month. The sector is large and complex, but it is likely that most CSP entities will apply for exemptions, claiming to be unable to afford the minimum wage of R3500, as workers are employed in non-governmental organisations and not-for-profit organisations that are underfunded and run mostly on scant government subsidies.

Overall, a generous guestimate considering those who are not in full time employment, these new minimums would improve wages for about a third of the total number of workers. Despite this, the national minimum wage has met opposition from within organised labour, which was inevitable given that South Africa’s largest trade union, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (Numsa) has, from the start of the process, been excluded in establishing the minimum wage. Numsa was expelled from the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) in 2014 for going against the constitution of the federation by refusing to support South Africa’s ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC). Subsequently a number of other unions left Cosatu, raising the number of unions left out of the national minimum wage dialogue.

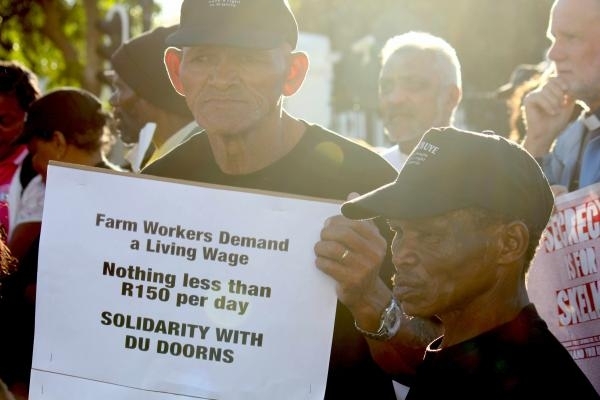

It was obstinate to think that concluding the minimum wage negotiations last year at the tripartite social dialogue forum, Nedlac, without the newly formed South African Federation of Trade Unions (Saftu) to which Numsa and the other unions that left Cosatu are affiliated, would go unchallenged. Numsa and Saftu have been demanding a higher minimum wage and arguing that the R20 an hour or R3500 a month is “slave wages” and that the minimum wage does not provide a living wage. Numsa and Saftu have remained true to the historical demand for a living wage and thousands took to the streets joining a national strike to support their call.

Poverty is dire in South Africa, more than half of the population lives under the poverty line and one fifth of the population lives below the food poverty line. Including discouraged workers, more than one third of the working aged population is unemployed, putting pressure on those that are earning at least half of which can be defined as the working poor. R3500 is not a living wage but it was not designed to be one. According to the National Minimum Wage Panel Report, “Ideally the NMW level should be close to the poverty line in order to reduce the incidence of working poverty, which will improve the welfare of working people and their families. In our view, the recommended level of R3500 per month correctly balances the trade-off between addressing low wages in South Africa and ensuring that any disemployment impacts do not exceed the positive gains for low-paid workers.”

The proposed minimum wage for South Africa would be much higher than that of neighbouring countries. In Malawi, the minimum wage is below the international poverty line at R430 (US $35) a month. In Zambia the minimum wage is R840 (US $70) a month and was last adjusted in 2012, not surprisingly, the national average wage in 2017 was about three times higher than that. Mozambique has set wages by sector; the lowest is farmworker wages at R690 (US $56) a month in agriculture and in the building sector the minimum wage is R1110 (US $90).

The closest national minimum wage in the region to that which is proposed for South Africa is in Mauritius, which was introduced for the first time in January this year set at R3200 (US $260). It increased salaries drastically especially for manufacturing workers in export processing zones (EPZ) where wages doubled. Whilst EPZ employees are amongst the few exceptions that have been given a lower wage rate than the national minimum, the government makes up the difference to ensure that workers all earn the same.

Compared to South Africa, Mauritius is a much smaller and less diverse economy with a lower population, small workforce and low unemployment rate at about seven percent in 2017. One notable difference is that it is has a far less flexible labour market than South Africa. There are fewer vulnerable workers in Mauritius, with the notable exception of migrant workers, as all companies and job contractors must be registered and have a proper operating license, which includes registration of employees with the Ministry of Social Security and prescribed process of paying minimum wages and issuing payslips amongst other requirements.

In comparison, only 60 percent of workers in the formal and informal sector in South Africa in 2017 were permanently employed, 46 percent of which were unionised. 5. 3 million non-permanent and therefore vulnerable workers make up the rest of South African workers and only five percent are unionised. The impact of the minimum wage in South Africa may be limited because these vulnerable and unorganised workers are not guaranteed fulltime employment and whist they may receive the R20 minimum an hour, their monthly wages could still be below R3500. In this way the impact of the national minimum wage can be diminished as flexibility in the labour market remains intact and vulnerable workers may be forced to work fewer hours in order to reduce their wages.

Whilst a national minimum wage will put pressure on collective bargaining, especially if wages in these sectors are already much higher than the proposed minimum, having a national minimum wage protects vulnerable workers that are not organised or covered by a bargaining agreement and in some cases it will improve agreements. For example, at least half of all construction workers earn below R3500 a month and in 2017, 55 percent were in vulnerable employment with a union density of just one percent compared to union density of 34 percent for those in permanent employment. There are a number of bargaining councils for the construction sector at provincial level. Currently the median minimum wage in construction is well below R3500 at R2390 (US $190). The lowest wages are found in Eastern Cape at R1393 for an unskilled labourer compared to R3489 in Gauteng.

When the national minimum wage comes into effect in South Africa, tensions amongst organised labour will need to be resolved to ensure inclusive representation in the National Minimum Wage Commission. The Commission is tasked with making recommendations annually to the Labour Minister and Cabinet on adjustments to retain real value of the minimum wage, factoring inflation and the cost of living amongst other considerations. It will be appointed by the Minister of Labour and made up of an independent chair and experts chosen by the Minister and nominees of organised business, labour and communities. There are three seats for organised labour on the Commission and four trade union federations. No doubt there will be jostling for the seats but Saftu holds power in numbers and militant activity, and will need a seat on the Commission if it is to be representative of organised labour.

* Aisha Bahadur is a consultant providing strategic support to civil society organisations including trade unions and focuses on African issues.