Poverty amidst plenty: How Africans are robbed of benefits of mineral wealth

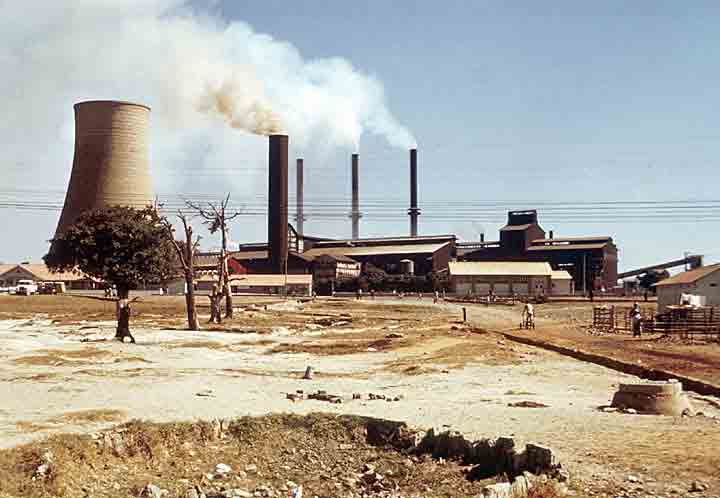

Africa has not benefited substantially from its mineral wealth. It is, therefore, essential for resource-rich nations to tailor their economic policies to effectively harness and utilise mineral revenues to improve the productivity of non-mineral sectors to break out of the extractive enclave.

The remarkable extractives-driven economic growth of the last decade across Africa failed to trickle down. It was jobless, it benefitted foreign corporates and the local elite, and it widened the gap between the rich and the poor. If Africa is to avoid the failures of the MDGs era and successfully transition from its present state to that foreseen by Agenda 2030 then it must better harness the potential benefits of its vast mineral wealth. African countries must institute fiscal reforms that will ensure that they are better positioned to derive maximum benefit from the next commodity price super cycle; they must plug loopholes that continue to facilitate the bleeding of much needed development revenues via illicit flows; countries must align all relevant local frameworks to the African Mining Vision, thereby putting the needs of citizens at the centre of their natural resource management agenda; and, crucially, Africa must unite in a broad and strong push for long overdue global tax reforms.

Mineral and oil dependent African economies are in distress as they face severe fiscal and balance of payment deficits. These are tough times indeed. From minerals to oil and gas, commodity prices have collapsed in the last few years. The price of copper, for example, has dropped by 67 percent and oil by 51 percent since 2011.

Falling commodity prices, especially those of minerals and oil, yet again highlight the perils of commodity dependence and the dominant extractive model on the continent. About half of African economies are classified as “commodity dependent”. That is, these nations derive a substantial part of their incomes from minerals and/or hydrocarbons.

To prop up their revenues and compensate for falling prices, Congo DR for example increased copper production but the country still suffered revenue decline of about $360 million. Equatorial Guinea also raised its oil exports by 13 percent but revenues plunged by about the same percentage.

In anticipation of prices going up, some African nations reduced supply. Angola and Nigeria for example cut their oil supply and revenues fell by about $5 billion for Angola. For Nigeria, the revenue decline was much larger, $26 billion, prompting President Mohammed Buhari’s government to withdraw fuel subsidies early in May. The government’s withdrawal of subsidies has pushed up the price of fuel overnight occasioning civil unrest across Nigeria.

Liberia’s revenue fell by two-thirds after the post-conflict state cut iron ore production. Zambia has also seen its revenues plunge by 23 percent after cutting back on copper production.

The corporates are benefiting

The slump in mineral prices is not bad news for all. Consider the case of mining companies: after reaping windfall profits at the peak of the commodity price boom, the plunging value of the currencies of many African mineral-rich nations is helping mining companies to cut their costs further.

South Africa-based gold miner, Goldfields Limited, which has operations in South Africa, Ghana, Australia and Peru, said its cash costs declined 3.1 percent in the second quarter of 2015 from a year earlier to $1,059 an ounce.

A lost opportunity for development

The recent commodity price booms, 2002-2008 and 2010 -2014, essentially benefited mining and oil multinational companies (MNCs). African economies lost a golden opportunity. From Ghana to Zambia, attempts by various African nations to review their fiscal regimes and tax provisions in mining contracts to raise additional revenue to fund development were mostly unsuccessful.

The continent ranks first or second in global reserves of bauxite, chromite, cobalt, industrial diamond, manganese, phosphate rock, platinum-group metals, soda ash, vermiculite and zirconium. In 2010, Africa’s share of diamond, chromite, gold and uranium was 57 percent, 48 percent, 19 percent and 19 percent, respectively, according to the Economic Commission for Africa.

However, fiscal regimes and public agencies governing the extractive sector in many African countries are weak and porous, making it much more difficult for these economies to effectively tax the sector to fund broad based socio-economic development. In many cases, companies enjoy excessive tax incentives[1] and African nations forfeit large portions of revenue which would otherwise have gone to fund national development. [2]

At the height of the commodity super cycle, a number of mineral rich countries sought to review their fiscal regimes and mining contracts to ensure that their economies shared in the high profits. Many of these efforts, however, failed not least because African economies reacted too late or faced major push back from mining MNCs and their governments. [3] Secondly, many African nations were unprepared for the boom and when the price surge was underway many more were too slow or unwilling to undertake the necessary measures.

Corporates are robbing Africa

The problem of low revenues from the extractives sector is further exacerbated by the extensive use of unethical tax avoidance, transfer mispricing and anonymous company ownership schemes by MNCs to maximize their profits at the expense of millions who lack basic services such as healthcare and education on the continent.

The January 2015 report of the African Union High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa [4] shows that the continent loses a colossal $50 billion [5] through Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs) each year, essentially via these aggressive tax planning schemes by MNCs and powerful local elites. The extractive industry, which is a key part of the commercial sector on the continent, is the biggest perpetrator of the theft of Africa’s financial resources through IFFs, the Panel emphasised. [6]

A dream for more effective natural resource revenues management deferred?

It is precisely to address this weakness and more that after decades of responding to externally driven transparency agendas, African governments embraced the Africa Mining Vision (AMV) in 2009 as the continent’s overriding framework for mineral sector governance. The AMV’s ultimate strategic goal is to use Africa’s mineral resources to promote broad-based socio-economic development of the continent. [7] One of the pillars of the AMV is the Fiscal Regime and Revenue Management [8]. Yet, seven years after its adoption, studies show that implementation of the AMV is slow at best. In a number of cases, measures taken by African governments undermine the AMV erode their own countries’ revenue bases.

Yet, tax revenue is the most sustainable and predictable source of development finance. Without adequate domestic revenue to underpin their development, it is practically impossible for developing economies such as Africa’s to comprehensively and concretely meet the basic needs of their citizenry, let alone industrialise.

The strong case for diversification

Crucially, natural resources are finite. It is, therefore, essential for resource-rich African nations to tailor their economic policies to effectively harness and utilise these revenues to improve the productivity of non-mineral, oil and gas related sectors to break out of the extractive enclave.[9]

Indeed, evidence from multiple sources shows that nations that rely largely on their mineral resources, characterized by widely permissive regulatory regimes, lose much more revenue than nations which have developed sector-specific fiscal instruments to optimise revenues. Ironically, this lost revenue is even higher during price booms.

Tiered weaknesses

On the whole, the inability of African countries endowed with mineral resources to reap the full benefits of the sector is down to a number of reasons. At the national level, the lack of political will by African nations to strike a balance between national interests and company interests is hampering the beneficiation of mining to African economies. This has also fed into a fierce and unnecessary competition among African economies to attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Attracting FDI is at the core of the dominant but dysfunctional extractives model which has reduced the African state to a taker of external initiatives and undermined nationally determined and driven agendas to maximize the benefits of the extractive sector to host countries. [10]

Secondly, in many countries, national agencies including revenue authorities are poorly equipped or lack the necessary capacity to adequately monitor and assess mining company records to ensure these companies pay their fair share of taxations.

At the global level, the financial architecture is heavily skewed against African countries especially those endowed with resources. As also noted by the AU High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa, mining MNCs are most culpable in shifting profits offshore to avoid paying appropriate taxes to African countries where they generate their wealth.

How the people of Malawi were robbed

A recent example from Malawi vividly highlights how the current international financial architecture and mining MNCs are bleeding African nations of investible capital through IFFs. Malawi lost $43 million in revenue over a six-year period from a single Australian mining company, Paladin, which owns a uranium mine in this impoverished southern African nation. The company used complex corporate structures to exploit loopholes in international tax rules after negotiating a huge tax break from the government. The company received tax incentives to the tune of $15.6 million. Paladin also used a subsidiary in Netherlands that has no staff to route the payments for management fees to Australia. [11] Thus through this aggressive scheme, the company succeeded in avoiding the payment of millions in tax contribution to the Republic of Malawi. [12] For a relatively poor country like Malawi, this is a significant loss of much needed resources.

Inadequate global response

It is against this backdrop that the G20 commissioned the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2013 to propose new rules to tackle tax cheating by MNCs under the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project.

The BEPS outcome, G20 adopted in Antalya, Turkey last November, thus represents the first serious global effort to combat widespread corporate tax cheating and related weaknesses that have handed MNCs significant advantage at the expense of mineral dependent countries in Africa.

That notwithstanding, the BEPS outcome failed to tackle the central flaw that allows MNCs to exploit the international tax system particularly the way in which tax rules treat subsidiaries of MNCs as if they were merely loose collections of “independent entities” trading with each other in “arm’s length” transactions. This allows companies, most of which are incorporated in the global north but do business in the south, to trade with subsidiaries set up in tax havens and/or secrecy jurisdictions, where they often have no real economic activity, so as to shift profits from African economies.

The G20 mandate for the BEPS project was that international tax rules should be reformed to ensure that MNCs could be taxed “where economic activities take place and value is created”. This implied a new approach, to treat the corporate group of a MNCs as a single firm, and ensure that its tax base is attributed according to its real activities in each country. Yet, the BEPS outcome continued to emphasise the independent entity principle.

Overall, this means that the BEPS outcome is nothing short of an attempt to patch up the broken old system. The BEPS essentially failed to capture the voice and interests of the global south especially on issues around permanent establishment and the arm’s length principle as opposed to unitary tax regime. There is therefore a need for an alternative to BEPS, possibly a UN Tax Body or even an African Tax Body.

* Kwesi W. Obeng is Policy Lead, Tax and Extractives, Tax Justice Network-Africa (TJN-A).

Endnotes

[1] These incentives range from tax breaks to stability clauses which ensures that companies enjoy these incentives over many years unchanged

[2] Tax incentives often awarded to mining companies in Africa include VAT exemptions, tax holidays, company-specific reduced rates of royalties; accelerated depreciation for the mining infrastructure; lower percentage of governments share from Product Sharing Agreements (PSA)

[3] In many cases, these calls for review were tagged at attempts at “resource nationalism” or “nationalization”

[4] African leaders also adopted a “special declaration” at their 24th summit as an expression of their resolve to tackle the huge scale of illicit financial flows from the continent to address Africa’s under-development.

[5] In real terms, the US$50 billion lost annually to could fund the construction of 500 modern hospitals across Africa. This breaks down to about nine (9) hospitals in each of Africa’s 54 states in just one year. Availability of such health infrastructure could literally transform the quality of life of the average Africa.

[6] The AU High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa was chaired by the former South African President, Thabo Mbeki. The US$50 billion is equivalent to 5.5 of Africa’s GDP.

[7] As the product of African inter-governmental process, it signals a concern by African states to submit to a collectively self-defined regime, rather than externally determined frameworks. Hence, the AMV’s goal is to create a “transparent, equitable and optimal exploitation of mineral resources to underpin broad-based sustainable growth and socio-economic development”. The AMV, thus, signals a paradigm shift in the role of minerals in African economies. The Vision and its Action Plan embody key reform demands that CSOs and various social constituencies had been making in respect of the mining regimes prevailing across Africa and the overall direction of national development strategies.

[8] The other clusters/work streams are: Geological and mineral information systems; building human and institutional systems; artisanal and small-scale mining; mineral sector governance; research and development; linkages, investment and diversification; environment and social issues; and mobilising mining and infrastructure development.

[9] Historically the extractive sector operates as an enclave with very minimal linkage to the broader economy

[10] 1992- World Bank Strategy for African Mining

[11] http://www.actionaid.org/2015/06/exposed-company-dodging-taxes-worlds-p…

[12] Put in perspective the lost revenue could have paid for the salaries of 8,500 doctors or 17,000 nurses of 39,000 teachers in one year. For a relatively poor country like Malawi this is a significant loss of vital resources.

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to [email=[email protected]]editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org[/email] or comment online at Pambazuka News.

This is a detailed exposé of

Ligação permanente

This is a detailed exposé of the issue of mineral resource exploitation in African countries. It is doubtful that this exploitation is any different from that seen with other natural resources such as agricultural export commodities. The factors cited here, especially the first "At the national level, the lack of political will by African nations to strike a balance..." is symptomatic of a deeper malady of entrenched corruption wherein leading figures in these countries are willing participants of unprecedented robbery of revenues from exploited resources. The vast majority African citizens for the most part have thus not benefited from mineral resources, as they fall victim to both internal and external agents of ruthless exploitation. Africans cannot realistically expect to play the victim card indefinitely when they have in their midst individuals who actually facilitate robbery by corporations, and in many cases get rewarded via corrupt means in committing these egregious practices.

The second factor cited: "Secondly, in many countries, national agencies including revenue authorities are poorly equipped...". Lack of preparedness in dealing with new developments and discoveries of mineral wealth cannot be divested from the first. The rush to embrace foreign corporations in haphazard fashion that is exacerbated by leader complicity through corrupt practices mentioned in this post can hardly be an excuse. Rather than exhaust resources prematurely, adequate preparations that ensure deriving maximum benefits become indispensable. Given the enormous losses mentioned in the article (which may be a gross underestimation), it may be wiser to postpone than rush into agreements with foreign investors which the governments cannot even oversee.