Beyond the T-shirt: What Che actually stood for

The famous portrait of Che Guevara graces T-shirts and posters the world over, but what did the revolutionary leader actually stand for?

Few revolutionaries are as well known as the late and great Ernesto "Che" Guevara. In fact, in what is the most ironic bastardization of his legacy, the communist leader’s iconic image is plastered on to T-shirts, posters and other mass-produced memorabilia and sold worldwide.

“There have been lots of attempts to commodify him,” said Helen Yaffe, author of "Che Guevara: The Economics of Revolution" and a professor at the London School of Economics, in an interview with teleSUR.

Speaking to the fact that people who may take in the consumer culture that surrounds him even if they haven’t delved into his works, she added, “Those who consume that (commodification), though, have an idea that he represents rebellion against the established order.”

But what are the actual economic ideas and philosophies behind this much-romanticized figure?

Today’s caricature of Guevara largely overlooks his contribution to Cuba's economic development and contributions to socialist thought. But the man whose image has survived the collapse of the Soviet Union and the changes to Cuban communism, continues to have a profound impact on leftists around the world.

“He was someone who was political, someone you looked up to,” Eren Cervantes-Altamirano, an Indigenous Latina writer and community organizer told teleSUR. Now a resident of Ottawa, Canada, she added, “I grew up in Mexico. I grew up with a particular idea of Che and his revolution.”

Talking about her Latin American identity, Cervantes-Altamirano said that the Argentine-born leader was highly symbolic for her growing up.

“I hold very dear those images (of Che) and the Cuban Revolution,” she said.

Guevara, however, was not born a revolutionary. He grew up in a middle-class Argentine family and trained to be a doctor, preparing to live a privileged life. But his eyes were famously opened to the harsh reality of capitalism when, as a medical student in his early 20s, he hopped on a motorcycle and went on a tour of South America. He found disease, destitution and illiteracy and from that point on, he labored to uplift the working class from Cuba to Guatemala to the Congo.

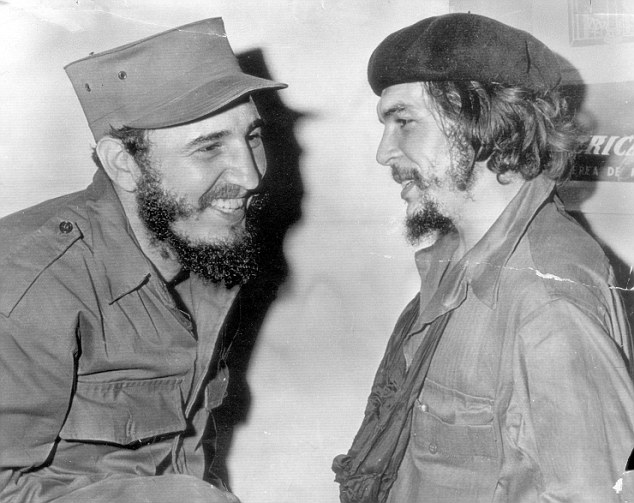

He later met Fidel Castro in Mexico City and worked alongside him to overthrow the U.S.-backed dictator, Fulgencio Batista, in what was known as the Cuban Revolution, which took place from 1956 to 1959. After its victory, however, the Revolution led to a broader based social and economic movement, where agrarian reform was one of its main tenets, and where Guevara was arguably one of its most profoundly influential orchestrators.

In the coming years, Guevara took posts as the director of the Industrialization program of the National Agrarian Reform Institute, INRA, head of the National Bank of Cuba, and later when the INRA became the Ministry of Industry, Guevara was appointed its minister. It was in these roles, Yaffe explained, that the guerrilla-leader-turned-economist carried out his Marxist policies, writing extensively about them, and leading by example in these actions.

“If you’re in a position of power, what practical policies can you develop that will affect how people think about their role in society?” said Yaffe, of Guevara’s central focus, which was getting the working class to develop a consciousness such that people worked for the benefit of society and from that received their reward, as opposed to working for a material gain.

Yaffe explained Guevara was constantly looking for solutions to stop the alienation workers felt from their labor. And it seems that this idea still reverberates in Cuba, and those in solidarity with the island today.

As a teenager in the mid 1990s, the LSE professor participated in what was the first brigade of the solidarity campaign, "Rock Around the Blockade" to Cuba from London, where she met other young people volunteering their labor in agriculture camps. When she probed as to why they were participating, the young Cubans told her, “Our country needs us. We need to defend the revolution and socialism.”

The brigades continue today, with different groups organising different brigades ever since the first years of the Revolution. Drew Garvie, secretary general of the Young Communist League, YCL, in Canada, who participated in one such brigade last year, told teleSUR how the movement has captured Che’s legacy.

“It was an idea of Che, in the early days of the Revolution, to organize volunteer work. Engaging in selfless labor was meant to help construct a new socialist spirit and a sense of solidarity in people. Che participated in this work on the front lines performing volunteer labour and leading by example,” Garvie explained. “On the brigade today, (participants) work alongside Cubans, usually doing agricultural work for a few mornings during the tour in order to show solidarity and build friendships between the brigade and Cuban workers. So in this sense the legacy of Che Guevara lives on in the brigade.”

Yeffe explained that another focus of Guevara’s was taking the most advanced, high-tech industries and fitting them into a Marxist framework. As the INRA leader, he did this by coordinating activities among the nation's industries, which had been nationalized. Later, as a part of the Ministry of Industry, this included centralized planning of the finances of Cuba’s economy, which after agrarian reforms, were central tenets of the post-Revolution communist nation.

“His budgetary finance system was very imaginative, creative and successful,” Yaffe said.

As the living standards of Cubans from before to after the Revolution rose, the U.S. blockade on the country in the wake of the Cold War posed a significant challenge.

“He never blamed the blockade,” Yaffe pressed, stating that his endeavor to stray from being dependent on the Soviet Union during this era was certainly frustrated by the blockade, but perhaps helped Guevara’s aims instead. “The blockade probably pushed him to develop a planned economy much quicker.”

Not afraid to be openly critical of the Soviet Union, as indicative in his 1967 Message to the Tricontinentalnt, he was not of the opinion that Cuba should just copy the Soviet system.

It was also his commitment to internationalism that inspires many today.

“Che’s life embodied a spirit of internationalism and anti-imperialism that is at the core of our work in Canada,” Garvie explained.

As Guevara was committed to struggles elsewhere, eventually leaving Cuba and his posts there to support the national liberation struggles of the African continent, YCL draws inspiration from this and is committed to struggles abroad, especially as they relate to Canadian imperialism.

“What binds young people in Canada to solidarity with the victims of Canadian imperialism abroad is the fact that we have the same enemies,” he explained. “For us, and Che, imperialism is an advanced stage of capitalism. To overthrow it for a world of peace and solidarity, we must fight for socialism.”

Guevara’s commitment to solidarity with diverse struggles also led to his ideas around a pan-Latin American identity. While his emphasis was on unity and a continent-wide pursuance of socialism, it’s important to consider that this discourse has some Latin Americans negotiating with their identities.

“As an Indigenous woman, and for Indigenous and Black communities in Latin America, the idea that Latin Americans should have a common identity poses an interesting dynamic,” Cervantes-Altamirano said.

Speaking on this facet of Guevara’s thoughts, she said, “(Che) was white. These points of privilege stick out to me as an Indigenous woman.”

While she is reluctant to glorify him, as she has written previously about, a lot of his principles resonate with her still today, especially his ideas of “freedom beyond neoliberalism.”

As Latin America faces two tides of movement towards the left, as well as the right, Guevara’s work in Cuba still inspires the left to advance in liberation struggles.

“There have been enormous advances towards sovereignty and democracy across Latin America, that I’m sure Che would have been very supportive of. However there has also been a reaction, led by the U.S. government and the capitalist class that is tied to imperialism in Latin America,” Gravie said.

“We now see a dangerous offensive taking place with the shock treatment that Argentina is going through under Macri, the coup against Dilma in Brazil and what is looking more and more like another coup attempt developing in Venezuela. Che’s goals are perhaps closer to being realized today, but there are also great dangers.”

Perhaps the most important of Che Guevara’s legacy is his anti-imperialist struggle, resonating with young people today, as it has for generations.

“To this day when young people think of internationalist anti-imperialist figures, Che Guevara is certainly among them,” said Garvie. “Tens of thousands of youth aim to strengthen the cause for which he also dedicated himself as a young person: the overthrow of imperialism around the world.”

* This article previously appeared in teleSUR.