Pan-Afrikanism and the quest for Black Power today

Instead of championing Afrika’s liberation from white supremacist monopoly capital, the African Union dedicates its time to fighting for Afrika’s integration into the global imperialist system. A thorough rethink of pan-Afrikanism in the 21st century is urgently needed.

[This talk was delivered at the Afrikan Liberation Day symposium, at the Drill Hall, Gauteng, South Africa, 25 May 2015.">

OPENING REMARKS AND DEDICATION

Let us start by expressing our humble thanks to the organisers for the honour of inviting us to come and share our perspective, on the range of issues that affect Black people in Afrika and other parts of the world. And for also affording us the privilege to be here and be in a position to learn from the many enlightening perspectives of others.

Allow us to also acknowledge the leaders of the various organisations of our people, our guests from the various parts of the Black world, and each and every Black sister and brother, here present. It is always heart-warming to be in the company of our own and freely and to honestly discuss all the issues that concern us as a people. This is an intellectual space we rarely afford ourselves and we definitely need to create more such spaces.

We meet here today on a very special and significant day, which as you know, was initially designated for the 15 of April and referred to as “Africa Freedom Day” and only became “Afrikan Liberation Day” on the 25 of May, 1963, after a historic meeting of Afrikan leaders in Ethiopia.

We decided to dedicate our talk here today to 2-year-old Onkarabile, 6-year-old Nkune, 7-year-old Sebengu and 9-year-old Mapule, of Verdwaal, who in October, 2011, left their home and undertook what later became a fatal 18-km journey in the sweltering heat in search of their mother and food. They never found their mother or food. A couple of days later, their tiny, life-less bodies were found in a veld, badly dehydrated and with hardly any food in their stomachs.

We dedicate our talk to 33-year-old Andries Tatane of Meqheleng, who, in April, 2011, was savagely attacked by a gang of police, shot with rubber bullets in the chest, resulting in his death on the spot. All of this happened in full view of members of his community.

We dedicate our talk to 17-year-old Nqobile Nzuza of Cator Manor, who in September 2011, was shot twice in the back by police, while running away and died shortly thereafter. The 34 Black workers of Marikana, who in August 2012, formed part of the Marikana Uprising and in defence of foreign-white-monopoly capital were mercilessly gunned down by the police.

We dedicate our talk to 27-year-old Mido Macia of Daveyton, who in February, 2013, was tied to the back of a police vehicle and after being dragged for a few meters, died several hours later in police custody. He was in his underwear and socks. His pants were later found at another part of the police station and a post-mortem stated that he died from a lack of oxygen and witnesses reported that he also had wounds to the head.

Our talk is also dedicated to 21-year-old Jan Ravimbo of Tshwane, who in January this year was shot at close range and killed by police, for simply demanding to know why they were taking his fruits and vegetables, which he was selling in the Tshwane central business district.

29-year-old Osiah Rahube, 26-year-old Lerato Seema and 64-year-old Bra Mike Tshele, who in January this year, were all killed by the police, when the community of Mothutlung, was protesting for something as basic as water.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The incessant violence that continues to be unleashed on the Black body - and is now also being perpetuated by governments that are led by our own - helps us to understand why our history, as a continent and people continues to be the most tragic paradox of human existence.

We have a glorious history characterised by breath-taking advances in the various spheres of human endeavour. However, our history is also punctuated by bloody but heroic tales of battles, against all manner of foreign invaders, rape, murder and lynching, land robbery, slavery and colonialism (in their classical and neo-classical forms), white racism and systematic genocide.

As the Tanzanian scholar, Issa Shivji observes, ours is “a tale of treasures at one end and tragedies at the other”.

And because of these tragic paradoxes in our history, today, we Blacks, in many respects, remain at the bottom of the human pyramid. Our powerlessness, in a ruthlessly anti-Black world, is perhaps best captured by Steve Biko, when he says:

“. …All in all the black man has become a shell, a shadow of man, completely defeated, drowning in his own misery, a slave, an ox bearing the yoke of oppression with sheepish timidity.”

In an attempt to undo the paralysis of Black existence and articulate Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power in a statist form some of our more intrepid and visionary forebears decided to form the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), which as we know, was officially ordained in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 1963. Ethiopia was perhaps one of the most appropriate places to give birth to such an important institution of our people - not just because it formed part of the spectacular tapestry of our ancient Nubian-Kemetian civilisations - but also because of how it gallantly resisted the organised violence of Italian white supremacy.

THE CONTEXT PRECEDING THE FORMATION OF THE OAU

To develop a fuller appreciation for why the OAU was not able to achieve some of its cardinal goals, is it critical that we understand the context that preceded the formation of this institution of our people. Many of Afrika’s leaders, who today are counted among some of the leading protagonists of 20th century Pan-Afrikanist thought and practice, were beneficiaries of the Pan-Afrikanist thought and practice of an earlier generation of Black thinkers and revolutionaries.

The Pan-Afrikanism of many of Afrika’s leaders was inspired by such imminent Black thinkers as Prince Hall, Paul Cuffee, David Walker, James Horton , James Johnson, Edward Blyden, who is regarded as the first Pan-Afrikanist thinker to use the concept of the ‘Afrikan Personality’ and portrayed Africa as “the spiritual conservatory of the world”, and Henry Sylvester Williams, who is credited with coining the concept of Pan-Afrikanism.

And of course, William Du Bois, George Padmore, Marcus Garvey, Cyril James and others such as Daniel Coker, Lott Carey, John Russwurrum, Martin Delaney, Henry Highland Garnet, and Alexander Crummell. Du Bois and Garvey are particularly critical because they played a pioneering role in giving Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power the form of a global political movement.

There are however two critical historical events, which also had a profound impact on the evolution of Pan-Afrikanist thought and practice and that of related Black radical traditions such as Black Consciousness. One is the Haitian Revolution, first led by Boukman in 1791 and later by Toussaint L’overture, which holds the distinction of ushering in the first Black republic in the western hemisphere in 1804. The other is Ethiopia’s decisive victory over Italy in the Adwa in 1896.

Fired-up by this rich political and intellectual heritage, a number of Afrikan states achieved one form of independence or another, and unsurprisingly, they expressed a growing desire for more unity within the continent. However, there was no common view on how this unity should be pursued and as a consequence two groups emerged in this respect.

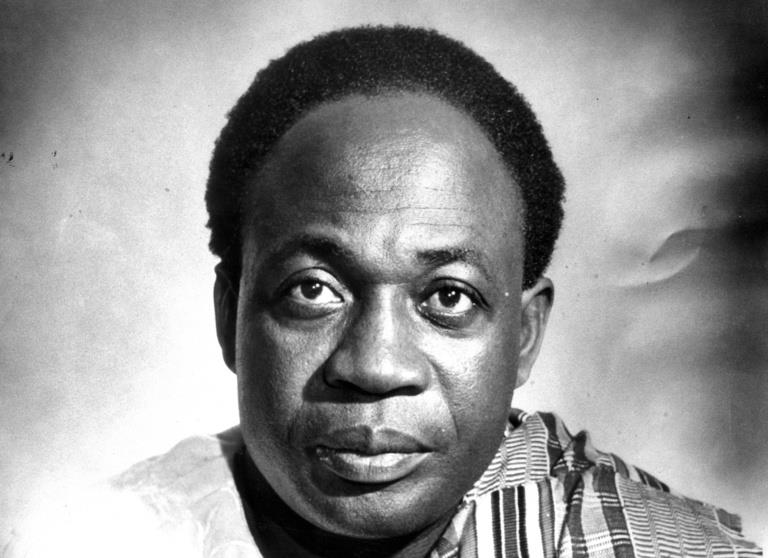

The one group was known as the Casablanca bloc, led by Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. This bloc included Algeria, Guinea, Morocco, Egypt, Mali and Libya and argued that unity should be pursued through a political federation. The other was the Monrovian bloc led by Sedar Senghor of Senegal, which argued that, unity should be achieved gradually, through economic cooperation. Its other members were Nigeria, Liberia, Ethiopia and most of the former French colonies.

Some of the initial debates took place in Liberia and were eventually harmonised when Ethiopian emperor Haile Sellassie invited the two groups to Addis Ababa, where, as we know, the OAU and its headquarters were subsequently established. And the Charter of the Organisation was signed by 32 independent Afrikan states.

In a number of respects, this was a critical milestone for Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power, both on the Afrikan continent and other parts of the Black world. But the birth of the OAU was also a big obstacle for the success of the project of western imperialism on the Afrikan continent.

And for this reason, western imperialism did all it could to frustrate this act of self-liberation. They bank-rolled those Afrikan leaders who were willing to sell their souls, orchestrated coups against those who refused to be co-opted, and assassinated those of our leaders who were openly and radically opposed to western control of Black people’s destiny.

THE CHALLENGES FACED BY THE OAU

Despite this major step, the OAU still remained largely divided. The former French colonies were still hopelessly dependent on France (something which persists even today). There was a further split along ideological lines, between those Afrikan states that supported the USA and those that supported the USSR, in the so- called Cold War of ideologies. The pro-Socialist bloc was led by Nkrumah, while, Felix Houphouet- Boigny, of the Ivory Coast, led the pro-Capitalist bloc.

Because of these divisions, it was difficult for the OAU to intervene decisively in intra or inter-state conflicts and for this and other reasons, some dismissed the OAU as “a glorified talk shop”, arguing that its policy of non-interference in the affairs of member states limited its effectiveness. This criticism became particularly strong in the context of the internal political crisis in Uganda, under Idi Amin.

In addition to the barrage of capacity and ideological challenges that the OAU had to contend with at inception, we wish to argue that, when viewed as a far-reaching statist articulation of Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power - the systematic assassinations of Patrice Émery Lumumba, Amilcar Lopes da Costa Cabral, Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane, Samora Moisés Machel, Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara, Malcolm X, Ramothibi Tiro and Bantubonke Biko - including the passing of Kwame Nkrumah, Mangaliso Sobukwe and not so long ago, that of Kwame Toure, were a big blow to the cause of Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power both in Afrika and the rest of the Black world. And we are not sure whether we have or will ever recover from these incalculable losses.

SUCCESSES OF THE OAU

In spite of these set-backs and systematic treachery, in our view, the OAU nevertheless made a number of strategic strides, some of which include giving greater structure and focus to Afrika’s resistance to western imperialism, laying the structural basis for continental unity and greater co-operation, and as stated earlier, giving practical expression to the cause of Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power.

This acknowledgement is particularly critical considering that, at the time of its formation, the so-called Cold War was in full swing and the leading actors in this conflict, the USA and Russia (and to some extent China), viewed territories such as Afrika as part of their battle-ground.

In addition to setting up a number of committees and agencies to facilitate various aspects of the national development of Afrikan states, the OAU’s Liberation Committee aided a number of liberation movements on the continent. It provided much needed weapons, training and military bases to various movements that were fighting against white-minority rule on the continent. Liberation movements in Azania also received various forms of OAU assistance.

HAS AFRIKA ACHIEVED THE OAU VISION?

Today, more than 50 years later, the OAU is no more and has been replaced by the African Union (AU) and most Afrikan countries (as previously defined by the borders of the white supremacist Berlin Conference of 1884-85), have formally raised their flags of independence, some have changed their names and the management of their respective states is now under the control of the indigenous people.

Because of this, can we confidently say Afrika has achieved the kind of liberation that the founders of the OAU envisioned? Put differently, has Afrika, under the AU, been able to free itself from the clutches of white supremacist-western imperialism? We think definitely not.

In our view, while some Afrikan states have made some governance and infrastructural advances, to a large extent, Afrika remains a colonised territory and today this colonisation is not obvious because, in the majority of cases, it happens indirectly. While some of the reasons are historical and external, one of the key factors that makes it difficult for the AU to advance the historical agenda of Afrikan liberation is the failure of many of Afrika’s contemporary leaders to grasp, the point that Issa Shivji makes, in an article titled, ‘The Struggle to Convert Nationalism to Pan Africanism: Taking Stock of 50 Years of African Independence’.

In this article, Shijvi argues that:

“To the extent that colonialism and imperialist oppression itself was ideologised in terms of White supremacy, the anti-racist, racial constructs and demands of pan-Africanists were anti-imperialist. It is important to keep this dimension of Pan-Africanism in mind – that in its genesis and evolution the ideology and movement was primarily political and essentially anti-imperialist.”

Flowing from this, even though it is the legitimate successor to the OAU, is Pan- Afrikan in its structure and some of its leaders occasionally invoke the ideas of the founders of the OAU, in their speeches, in the manner that it functions, the AU is not necessarily a Pan-Afrikanist instrument, in the ideological sense, as described by Shivji.

For instance, the AU has located the development of the Afrikan continent within the hegemonic-western-neo-liberal ideological paradigm, by among others, setting as key development benchmarks, the installation of liberal democracy, holding regular elections, having free-market-economies, that are mainly geared towards attracting foreign investment and meeting the targets of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Nothing about reclaiming the land, wealth and dignity of Black people, that were (and continue to be) taken through covert and overt imperialist conquests.

One of the programmes that perhaps best illustrates the AU’s inclination towards neo-liberalism is the New Partnership for Africa’s Development or NEPAD. The dominant thinking within the AU seems to be that, Afrika’s economic problems are primarily problems of poor governance, infrastructure, low economic growth rates and armed conflict, and once these are solved the majority of Afrika’s people will automatically experience meaningful development in their lives. Or as the gospel of the high-priests of capitalism often goes: “The benefits of economic growth will trickle down to all”. What about who owns the wealth of Afrika?

This thinking is not just neo-liberalist to the core-but seems to be operate along a logic that says, in order to advance themselves meaningfully, Afrikan states and Blacks in general should behave as though the fight against slavery, white supremacy and western imperialism is over, and that all that Afrikans must now focus on is to manage their countries and economies “responsibility”, and the rest will take care of itself.

It is also instructive to note that, given its influence at the time, through its former head of state President Thabo Mbeki, South Africa was instrumental in shaping the AU’s neo-liberal deportment. Therefore, instead of championing Afrika’s extrication from the clutches of white supremacist-monopoly capital- the AU dedicated a lot of its time to fighting for Afrika’s integration into the global power constellation of white-supremacist- western imperialism.

As a consequence, today, much of Afrika’s mineral and other forms of wealth, remain under foreign control. This is not always obvious, because many of Afrika’s governing elite are essentially the Mantshingilanes of western interests. This should bring us closer to the real reasons behind the persistence of armed conflict in Afrika (and other parts of the world), particularly in such mineral-rich countries as the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic, Sudan, Nigeria and Libya.

It would be extremely difficult to find an armed conflict in Afrika which is not, in some way, a manifestation of the phenomenon of proxy imperialist wars. Just as in the era of the OAU, armed conflict in Afrika today (and other parts of the world) is largely orchestrated by western intelligence agencies in defence of the interests of foreign multi-national corporations.

This is particularly true for those MNCs involved in the oil business and explains why, as alluded to earlier, imperialist nations like France, continue to control the political and economic affairs of their former colonies on our continent. Therefore, to attribute armed conflict in Afrika purely to ethnic or religious chauvinism or state corruption is not just an act of intellectual laziness, but also a treacherous tactic to conceal the real cause of armed conflict in Afrika - which is economics. Put differently, religious and ethnic chauvinism are merely used to fuel the fire - they don’t start it.

The hegemony of neo-liberalism over Afrika’s contemporary politics and economics also helps us to understand why it was possible for western intelligence operatives to come into Libya and ferment the kind of climate that led to the brutal assassination of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi.

History must record that, even though they had the option to abstain, as Russia, China, Brazil and others did in March 2011, at a meeting of the UN Security Council, South Africa, Nigeria and Gabon, voted in support of imperialist countries such as the USA, France and Britain, to get the repugnant Resolution 1973 passed. Their votes effectively facilitated the armed invasion of a fellow Afrikan state and legitimised the brutal political assassination of a fellow Afrikan. Is it unreasonable to wonder whether they could not have done the same thing to President Mugabe? Definitely not!

The brash impunity of neo-liberalism is perhaps best demonstrated by the fact, despite the many atrocities that they have and continue to commit, that the Western warlords of our time, like George Bush (senior and junior), Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, David Cameron and of course Barrack Obama are not likely to appear in front of the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity in various parts of the world and in particular those committed against Black people.

These and related factors overwhelmingly point to the fact that, not only has the AU betrayed the OAU’s mission of liberating Afrika, but also, as a collective, the current crop of Afrikan leaders, are not advancing a structured project against white-supremacist-western imperialism. And it is for this reason that the Black radical movement in Azania must never apologise for supporting Black people in Zimbabwe in their quest to reclaim their land and wealth.

RE-IMAGINING BLACK POWER IN THE 21ST CENTURY

One of the cardinal challenges that arise out of the disturbing context we have painted is an urgent need for a radical and fearless re-think of the meaning of liberation, Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power in the context of where Black people find themselves today. To fulfil this task honestly, at a theoretical and ideological level, those concerned with the destiny of Black people must grapple with some of those vexing questions that others prefer to avoid. Some of these are:

• What do Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power, mean in the context of radical Black nationalisms that fail to properly theorise around the questions of land and the national question, the race, class and gender dialectic, ethnic and religious chauvinism, crude afro- and homophobia, neo-liberalism and predatory environmental imperialism?

• What do Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power mean in the context of the long-standing struggle for self-determination by the Sahrawi of Western Sahara under the leadership of the Polisario Front?

• What do Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power mean in the context of the burgeoning struggle for self-determination by the Toureg of Mali, under the leadership of the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA)?

• What do Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power mean in the context of the recent uprisings in Arab-speaking Afrika?

• What do Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power mean in the context of the over 40-year liberation struggle of the Black (Black is used here for emphasis) Melanesians of Papua, under the leadership of the OPM, KNPB and the Free Papua Movement? From the 1960s, on wards, successive Indonesian regimes have been carrying out ruthless campaigns of genocide against the Melanesians of Papua and West Papua, systematically killing over 500 000 Black people. This genocide against our relatives is probably the biggest political injustice of our time yet it doesn’t enjoy the attention it deserves. In fact, it is almost a forgotten genocide.

• What do Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power mean in the context of the continued persecution of Mumia Abu-Jamal and Assata Shakur by the American government?

• What do Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power mean in the context of the structural anti-Black violence that Blacks in North, South and Central America, the Caribbean, Europe, Asia, the Pacific and the Middle East, continue to be subjected to?

• What do Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power mean in the context of a ruthlessly uni-polar world, which is characterised by the military authoritarianism of the USA and its allies, under the leadership of a US President who is partly of Afrikan extraction?

• And in the Azanian context, what do Pan- Afrikanism and Black Power mean in the context of politically weak Pan-Afrikanist and Black Consciousness political formations, the growing grip of anti-Black neo-liberalism on mainstream Black politics, and the profound paradox wherein an essentially landless- economically enslaved, powerless Black majority, periodically pauses , to proudly celebrate “Freedom day”?

CONCLUSION

As we seek answers to these and other such questions, we should perhaps also bear in mind the point made by the Azanian scholar, Pumla Gqola, in her book, ‘A Renegade Called Simphiwe’ wherein she argues that:

“...It is important that a critique of power not end with reaction, but that it goes further to imagine something new, more exciting, and more pleasurable. Picture what we can create if we dare to give ourselves permission to imagine freely. It is important to create alternatives just as it is important to speak truth to power”.

If we are indeed going to create alternatives, as Gqola suggests, and are to give Black people a real and meaningful fighting chance to reclaim their dignity, then there are few urgent and practical tasks we must perform.

Firstly, there is a need to strengthen (and protect) existing Black institutions that are geared towards the advancing the ideals of Pan-Afrikanism and Black Power and where possible, build new ones, particularly in those areas where poor Black people reside.

Second, white supremacy, slavery, colonialism, capitalism and now neo-liberalism are essentially systematic and structural forms of violence against Black people and the poor people in general, and for this reason, we need to have programmes that deliberately equip our people (especially Black young people), to defend themselves against these (and related evils) - not just intellectually, but also physically, if the situation so requires (as it often does). People don’t usually mess with groups that know how to defend themselves.

Third, in the Azanian context, those of my generation, who are associated with the various Pan-Afrikanist, Black Consciousness and Socialist oriented organisations, must cease to be petty, swallow their narrow-minded pride and begin to have a serious conversation about forming a united Black Front. Our people and their daily reality urgently require collective action. However, we must guard against such a conversation being driven by what Michela Wrong refers to as the “It’s our turn to eat” mind-set.

Such a conversation must be inspired by the need to re-ignite the Azanian Revolution for land and genuine national liberation, and give our people genuine and renewed hope. Accordingly, this conversation must include Pan-Afrikanist and Black Consciousness movements in North, Central and South America, The Caribbean, Europe, Asia, the Pacific and the Middle East.

I would like to leave you with the words of Pianke Nubiyang, who believes that:

“It is time for change and that change will come when Blacks who speak Spanish, French, Dutch, Portugese, Yoruba and Arabic (in Sudan) realize that we are Black Afrikans first and foremost and no matter which colonial language we speak, RACE IS THE ISSUE, and in Latin America as well as Arabic-speaking North Africa, or even West Papua, its our Blackness and Afrikan being that pushes people to attack us.”

Inspired by the wisdom of Nubiyang, my main message to us, here today, is that, given where we find ourselves as a continent and as a people, it does seem to me that, there can be no liberated Afrika or Black Power, if there is no Black unity first.

*Veli Mbele is a South African essayist, Black Power activist and political commentator.

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org or comment online at Pambazuka News.