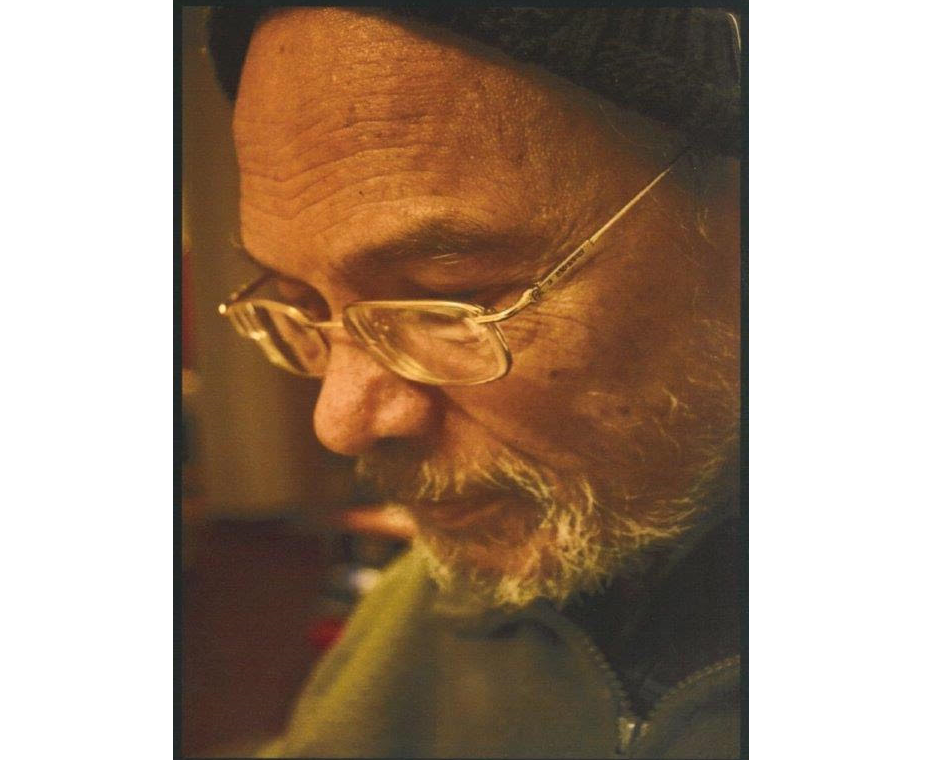

A tribute to Kenneth Abrahams

Throughout his life, he refused to collaborate with the ruling elite and remained committed to the principle of internationalism as witnessed by him joining up with Namibian migrant workers in Cape Town in the 1950s, or later being the people’s doctor in Lusaka where he treated fighters from various national liberation movements in southern Africa.

The last public appearance of Kenneth Abrahams was at a socialist conference in Windhoek in September 2012, where he delivered a long tribute to his former comrade, Neville Alexander. The Marxist Group that organised the conference was certainly honoured to have him there, and regarded his presence as an affirmation of his life-long commitment to socialism, as well as confirmation of the link between an older generation of activists and a younger generation. We understood that Abrahams had dedicated his life to the idea that another world is possible, in contrast to the barbarism of capitalism. And, indeed, the formidable intellect of Abrahams would be greatly missed as a co-thinker in trying to find solutions to contemporary crises in nation-building, health, education, gender relations, the economy, the ecological system, etc.

Given the historical significance of Abrahams’ contribution to the Namibian anti-colonial struggle, it is worthwhile to quote extensively from his conference presentation: “(I)n the 1950s … we were all members of the Non-European Unity Movement (NEUM), Society of Young Africa (SOYA) and NEF (an Educational Fellowship). We were members of the Cape Town Branch of Swapo when it was still called OPO (Ovamboland People’s Organization) and met at Timothy’s Barbershop in Green Point as from 1958. This Branch was for a long time the most energetic Branch within Swapo... The Branch included several people who rose to prominence within Swapo in later years including Herman Toivo ya Toivo, Hifikipunye (Lucas) Pohamba, Andreas Shipanga, Solomon Mifima, Peter Mueshianga, Peter Nanjembe, Louis Nelengani and Maxton Joseph.”

Abrahams, who had been influenced by the ideas of non-collaboration of the Unity Movement, was not only a leader of the Cape Peninsula Students Union, but was also part of the formation of OPO, the drafting of the SWAPO constitution and ultimately played a significant role in changing SWAPO into a guerrilla movement. Throughout his life, he refused to collaborate with the ruling elite, and remained committed to the principle of internationalism as witnessed by him joining up with Namibian migrant workers in Cape Town in the 1950s, or later being the people’s doctor in Lusaka where he treated fighters from various national liberation movements in southern Africa, and of course supported many Namibians such as Werner Mamugwe and others.

In his conference presentation, Abrahams went on to refer to fund-raising activity that they participated in in the 1960s in Cape Town: “we held dances in a hall in District Six under the fake name of the Rovers’ Soccer Club.” He belonged to a small group in Cape Town in the 1960s that founded two organisations, the Yu Chi Chan Club (YCCC), which later became the National Liberation Front (NLF), that engaged in discussions about Maoist-type protracted guerrilla warfare against the apartheid regime. But,

“… by the end of 1963 some of our comrades were in prison and we were in exile. We should note that more than twenty of our Swapo members were simultaneously members of both organisations. Some were detained and questioned aggressively but not a single one was prepared to give evidence at the trial (of Neville Alexander and others). Some were even present when we met as members of the Swapo Central Committee in Dar es Salaam to discuss a strategy for guerrilla warfare and to form the Peoples’ Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN).”

After the clampdown on the Yu Chi Chan Club, the apartheid security police attempted to arrest Abrahams in Rehoboth, but he was protected by an angry community that were not prepared to have their only medical doctor taken away. After Abrahams hid in the mountains for a few days, he, Andreas Shipanga, Hermanus Beukes and Paul Smit had to march across the border into Botswana in August 1963. However, they were abducted - with a gun held to Abrahams’ head - inside Botswana by apartheid police in plain clothes, and taken to prison in Gobabis where they were charged with leaving the country illegally. Abrahams was flown to Cape Town and there charged with sabotage. Following an international outcry, he was released and went into exile to Tanzania in 1963, and became a member of the central committee of SWAPO.

Our impression is that Abrahams had an entryist position in an attempt to infuse the Namibian national liberation movement with democratic and socialist ideas, and this made sense in the context of a low mass consciousness, but the conservative leadership would have none of any radicalism. It might be noted that Abrahams was suspended from SWAPO in 1964, reportedly after he had started enquiring about how funding was being used in the organisation, but he has apparently not been formally expelled up to this day. At the request of the SWAPO leadership, Abrahams was declared a prohibited immigrant in Zambia in 1968, and was eventually granted asylum in Sweden. After the democratic rebellion of the Shipanga faction in SWAPO, Abrahams and others formed SWAPO Democrats (SWAPO-D) in June 1978 in Stockholm, in an attempt to democratize the anti-colonial struggle of Namibia. So, to emphasize, the struggle of Abrahams and others within SWAPO was about a democratic ethos, and giving the organisation a left-wing direction.

During that time in Sweden, Abrahams was the editor of a publication called The Namibian Review, which he continued for several years even after returning to Namibia in 1978. This speaks to the value that he had attached to open discussions within the movement, and the fact that any struggle is first and foremost about ideological contestation. In Namibia, Abrahams got involved in the running of several projects under the broad banner of nation-building. He helped to initiate the Namibia Nationhood Coordinating Committee in an attempt to give proper articulation to the slogan of ‘One Namibia One Nation’, and to create a sense of nationhood, self-reliance and non-racialism among the colonialized people. Needless to say, these issues persist in contemporary Namibia in the context of the ideological fracturing of the ruling elite, who have now served their historical purpose for the capitalist system.

It should be noted that Abrahams and others had clearly shifted their political strategy from guerrilla warfare to a Gramscian focus on enriching mass consciousness and enhancing the hegemony of the subaltern, especially in an historical era of interregnum. This remains a crucial lesson for activists today when the neo-colonial project in Namibia has reached its end.

It should be said that Abrahams was also active on the educational front and was a member of the Namibian Educational Forum. In the 1980s he was editor of the Namibian Voice of the Students, a Namibian National Students Organisation (Nanso) publication, but more importantly was involved in the establishment of the Jakob Marengo Tutorial College, as well as the People’s Primary School, in order to give expression to a people’s education. Abrahams admitted that “he had become fascinated by the tactics used by Jakob Marengo in the 1904–1907 War of Resistance to German Colonialism which he (Abrahams) had discovered when (they) we were studying guerrilla warfare in the days of the YCCC.” And that he was “also shocked by the extent to which the memory of Marengo had already disappeared from the Namibian consciousness. In 1985 (they) established a school which (they), naturally, named the Jakob Marengo Tutorial College… Its motto remains Education for Liberation”.

In an effort to enhance a people’s history of Namibia, for example, Abrahams and others organised a seminar of the Namibia Review Publication in Windhoek in December 1982, where an essay on Marengo was presented. In the context of the ongoing education crisis in the country, there is a need to revisit many of these notions of a people’s history, a people’s education or education for liberation.

It should likewise be highlighted that Abrahams was a feminist, and that he participated in setting up the Namibian Women’s Association (NAWA) in the 1980s, as well as the first girl child movement in the 1990s. So the political life of Kenneth Abrahams has certainly not been in vain. In fact, on the contrary, he had made a remarkable contribution to the national liberation of Namibia and the advancement of left-wing ideas in the country.

Thus, today we say: Hamba Kahle comrade Kenneth Abrahams. Rest in power. The struggle for a socialist Namibia continues.

* Shaun Whittaker and Harry Boesak are members of the Marxist Group of Namibia.

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHORS AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to [email=[email protected]]editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org[/email] or comment online at Pambazuka News.