Pan-Africanism and trade unions in the post-colonial era

Workers’ protests and resistance movements that preceded Africa’s independence demonstrated the working class’s quest for a continental effectual workers alliance.

Western imperialism was built off of the exploitation of African land and labour from the mid-to-late 15th century through the conclusion of the Atlantic Slave Trade and the consolidation of classical colonialism at the end of the 1800s.

Leading African historical scholars have documented the link between the tremendous profits accrued through the plantation system in the Caribbean, South America, Central America and North America and the rise of industrial capitalism [[i]].

The capitalist modes of production as exemplified in shipping, commerce, banking, commodities production and services all grew into formidable sectors during the period of the 18th and 19th centuries. By the dawn of the 20th century and the eventual advent of the First World War, heavy industry had become the engine for the competition between various imperialist states seeking domination of global markets.

Of course, the resistance of African workers, including agricultural, domestic and extractive-manufacturing, developed rapidly as an inevitable response to the horrendous conditions under which people laboured. Peasant societies were often turned into a rural proletariat when the character of their labour production was exclusively designed to enrich the colonial powers.

As African farmers were driven from their traditional lands to work in the mines, large-scale agricultural production businesses, docks, mining facilities and factories, the conditions were conducive to the creation of labour organisations. In the Union of South Africa, formed in 1910 as result of the compromise over the conflict between the Boer and British settler populations aimed at the consolidation of white-minority rule, African miners began to demand better pay and working conditions through work stoppages at Dutoitspan, Voorspoed and Village Deep mines in January 1911. Nonetheless, they were forced back into the mines by the repressive tactics of the bosses supported by their European worker counterparts [[ii]].

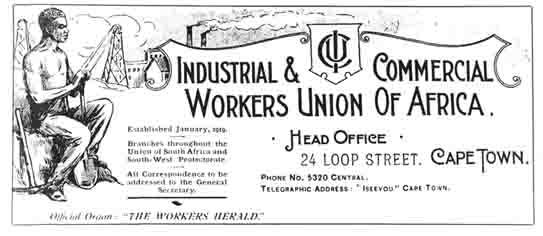

When the white miners went out on strike in 1913, they were committed to raising the standard of living for the European workers only, leaving African workers isolated for the purpose of super-exploitation. After WWI, the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) was formed under the leadership of Clements Kadalie of Nyasaland (Malawi).

During the period of 1920-22, there were strikes and violent unrest in the mines where both African and white workers put forward their demands. The mine bosses sought to divide African and European miners by laying off whites to hire Blacks at inferior wages.

By 1922, white workers were in revolt in the Rand and managed to seize control of several towns while waging a reign of terror against African workers, murdering numerous people. The capitalist-colonialist regime would put down the white miners’ rebellion through aerial strikes against their meeting places and the killing of hundreds of European workers. The disturbances prompted the passage of the Industrial Conciliation Act of 1924 designed to win labour peace between the mine owners and European workers.

Eventually the racist government sought to deport ICU leader Kadalie from South Africa. A South African historical website says of the developments in 1926 that: “Clements Kadalie, originally from Nyasaland, was targeted utilising the South Africa’s pass laws, and was convicted for entering Natal without a permit. In a May Day address, Kadalie urges workers to overthrow capitalism and establish a workers’ commonwealth. However, by December, under the influence of a liberal coterie including Margaret Ballinger, the ICU adopted a motion at the national council meeting prohibiting members of the ICU from belonging to the Communist Party. Despite revolts at branches in Port Elizabeth and Johannesburg, the decision was endorsed at the seventh annual congress in April 1927. The Mines and Works Amendment Act of 1926 firmly establishes the principle of the colour bar in certain mining jobs. The South African Trade Union Congress (TUC) was formed. December saw an ultimatum being issued to the communists within the ICU to choose between the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) and the ICU. Those who choose not to resign were expelled [[iii]].”

Workers fight back in Africa alongside the independence movement

These labour actions by African workers were not limited to South Africa. In West Africa there were strikes and rebellions in Nigeria, Sierra Leone and the Gold Coast (Ghana). In Sierra Leone, still a British colony established after the conclusion of American war of separation, railway workers struck in January 1926 demanding higher wages. The work stoppage lasted for several weeks until broken by the colonial authorities.

Nigeria experienced the “Women’s War” of 1929-1930 when the threat of taxation and the restructuring of traditional life sparked a rebellion which lasted for several months in the eastern region of the country. Women torched colonial buildings and attacked British interests as well as warrant chiefs who had been collaborating with imperialism. The events represented the advent of a nationalist movement which transcended ethnic lines [[iv]].

Gold Coast public workers walked off the job in 1919 and 1921. Other strikes took place in the gold mines during 1924 and 1930. All through the decades of the 1930s there were industrial actions in the railway, mining and public works sectors. The most well-known strike took place among railway workers in 1939. During World War II, in 1942, there were ten major strikes in the British colony [[v]].

These developments were integral to emboldening of the struggle for national liberation after the conclusion of the second imperialist war. Two conferences held in Britain during 1945 were critical in raising the profile of African workers in the movement towards independence, Pan-Africanism and socialism.

The World Confederation of Trade Union (WFTU) was founded at a conference in England in 1945 and enjoyed the participation of African workers. In a forward to “The Voice of Coloured Labour” by George Padmore, he noted: “The wide and representative character of the Colonial delegation to the World Trade Union Conference in February was significant and encouraging. It was significant for the fact that for the first time in the history of international labour, coloured Colonial workers – the most oppressed and exploited section of the world proletariat – were given the opportunity of voicing their grievances and of expressing their hopes and aspirations through their trusted leaders. It was encouraging because in discussing the question of a new international trade union organization, the white working class trade union movements of Europe and America, which have hitherto ignored the coloured workers, are apparently beginning to recognize that ‘Labour in the white skin cannot emancipate itself while Labour in the black skin is enslaved.’ This awareness was manifested in drawing the long-neglected and forgotten millions of Colonial workers into the world fraternity of labour [[vi]].”

Padmore went on to emphasise the meteoric growth in organised labour activity in Africa and other regions of the colonial world during the WWII: “Colonial delegates came from Nigeria, Gold Coast, Sierra Leone and Gambia in West Africa; from Jamaica in the West Indies; British Guiana in South America; from Palestine, Cyprus, and elsewhere. It is noteworthy that the Northern Rhodesian Mineworkers’ Union was represented by a white man, for the Colour Bar in that colony excludes African miners from entering the union…. The Nigerian Trade Union Congress, which came into being only three years ago, now boasts a membership of 500,000 and 56 affiliated unions, covering transport, mining, dock-labour, seamen, public works, government employees, etc.”

The Fifth Pan-African Congress (PAC) was convened later in October 1945 in Manchester. This gathering was pioneering as a result of its mass character encompassing figures such as Kwame Nkrumah of the Gold Coast, George Padmore of Trinidad, Amy Ashwood Garvey of Trinidad and W.E.B. Du Bois of the United States. What made the summit so significant was the representation from African workers and farmers through their organisational formations.

A resolution passed at the Fifth PAC called upon the masses to rise up and fight for national liberation and social justice. Recognising that independence was the initial phase in the movement for total freedom, the “Declaration to the Colonial Workers, Farmers and Intellectuals” says: “The object of imperialist powers is to exploit. By granting the right to Colonial peoples to govern themselves that object is defeated. Therefore, the struggle for political power by Colonial and subject peoples is the first step towards, and the necessary prerequisite to, complete social, economic and political emancipation. The Fifth Pan-African Congress therefore calls on the workers and farmers of the Colonies to organise effectively. Colonial workers must be in the front of the battle against Imperialism. Your weapons-the Strike and the Boycott-are invincible [[vii]].”

Two independence roads in the quest for continental trade union unity: The All-African Trade Union Federation and the Organisation of African Trade Union Unity

The struggle for the acquisition of national independence would swiftly emerge after WWII. From the rebellions and general strikes in the Gold Coast from 1947-1950; the Egyptian Officers Coup of 1952; the ascendancy of Kwame Nkrumah and the Convention People’s Party (CPP) in establishing a transitional government in the soon to be renamed Ghana from 1951-1957; Guinea-Conakry’s independence vote of 1958; the Defiance Campaign Against Unjust Laws in South Africa between 1952-1956; Sudanese declaration of independence in 1956; Algeria’s National Liberation Front (FLN) war of independence from 1954-1961; etc., Africa was clearly on the move.

As a working class specific counterpart to Pan-African gatherings such as the Conference of Independent African States in Accra in April 1958 and the All-African People’s Conference in the December of the same year, by 1961, the All-African Trade Union Federation (AATUF) was established in Ghana as well. The project was supported by the CPP of Ghana under direction of Nkrumah as a corollary of the aims of creating a United States of Africa under socialism.

After two preparatory meetings in Accra during November of 1959 and one year later in 1960, the first conference of the AATUF was held in Casablanca, Morocco in May 1961. From its inception there was a split between the Ghana Trade Union Congress (TUC) and other allied labour organisations on the one side against those groups which wanted to maintain affiliation with the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) based in the United States.

AATUF took a position of non-alignment encouraging the non-affiliation with both the World Federation of Trade Union (WFTU) and the ICFTU. Sensing the trends towards non-alignment, the WFTU urged support for the AATUF encouraging its affiliates on the continent to join wholeheartedly the Pan-Africanist formation. Those unions, which rejected the concept of non-affiliation outside of Africa were subject to derision as Tom Mboya, the Kenya trade unionist and later government minister in Kenya, who was condemned by the AATUF as an agent of imperialism. The ICFTU had assisted in the establishment of the African Trade Union Confederation (ATUC) founded in 1962 as an attempt to counter the influence of the AATUF [[viii]].

However, by February 1966, the CPP government under Nkrumah was overthrown in a US-backed military and police coup. The unelected regime made a rapid turn to the West and sought to eliminate all of the former policies initiated over the previous decade-and-a-half by Nkrumah. Losing one of its key supporters politically and financially, the AATUF was plunged into a deepening crisis [[ix]].

By 1973, the AATUF had collapsed due to its waning support from various governments and lack of funding. The Organisation of African Trade Union Unity (OATUU) was formed by the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, the location of its secretariat.

Today, the OATUU has 73-affiliated labour organisations representing workers in 54 states across the continent and its headquarters is located in Accra, Ghana. Of course, Ghana politics is far afield from the socialist and Pan-Africanist orientation of its early years under Nkrumah. The OAU was transformed into the African Union (AU) in 2002 in an attempt to move more urgently towards political unity, social sustainability and economic development.

An entry on its website says of the federation: “The Organisation of African Trade Union Unity (OATUU) was founded in April 1973 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Prior to the founding of OATUU there existed three Pan-African Trade Union Organisations, namely: All-African Trade Union Federation (AATUF), based in Accra, Ghana; African Trade Union Confederation (ATUC), based in Dakar, Senegal; and, Pan-African Workers Congress (PAWC), based in Banjul, the Gambia. Each of the three organisations represented different trade union tendencies. The founding of OATUU put an end to the existence of the three Pan-African trade union organisations, having voluntarily dissolved themselves in Addis Ababa in April 1973. At the founding of OATUU, although the overwhelming majority of national trade union centres supported its creation, yet there were few national centres that had reservations. It was not until March 1975 at the first meeting of OATUU General Council in Accra, Ghana that all the national trade union centres in Africa eventually agreed to become fully-fledged members of OATUU, thereby ensuring the total unity of African workers [[x]].”

Conclusion: The role of workers in African development and unification

These events involving the evolution of trade unionism and organised worker activity in Africa mirrors the political trajectory of the continent since the rise of the independence movements during the post-WWII period. Although there have been fluctuations in the economic performance of independent African states over the last two decades, the continent remains largely dependent upon the exigencies of the world capitalist system.

Therefore, the plight of workers in regard to the distribution of real wages and national wealth is often overlooked in evaluations related to notions of growth and development. The individual wealthy of Africa and the rising salaries of the middle and upper income strata do not necessarily correlate with the status of the majority still made up of the working class, farmers and youth.

Africa can only achieve genuine development when the proletariat and farmers are empowered to make the necessary decisions guiding the future of the continent. Within the existing framework of neo-colonialism, the people of Africa will remain second-class citizens to the dominant position occupied by the Western industrialised states utilising their domination of the global markets and militarism.

*Abayomi Azikiwe is Editor at Pan-African News Wire

Endnotes

[i] https://archive.org/stream/capitalismandsla033027mbp/capitalismandsla033027mbp_djvu.txt accessed on 15 May 2019

[ii] https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/rand-rebellion-1922 accessed on 15 May 2019

[iii] (https://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/timeline-labour-and-trade-union-movement-south-africa-1920-1939) accessed on 15 May 2019

[iv] https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/aba-womens-riots-november-december-1929/ accessed on 16 May 2019

[v] https://www.jstor.org/stable/524586?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents accessed on 16 May 2019

[vi] https://www.marxists.org/archive/padmore/1945/labour-congress/index.htm accessed on 16 May 2019

[vii] https://www.marxists.org/archive/padmore/1947/pan-african-congress/ch03.htm accessed on 16 May 2019

[viii] https://www.nuffield.ox.ac.uk/media/1887/african-trade-unions.pdf accessed on 16 May 2019

[ix] https://muse.jhu.edu/article/197821 accessed on 16 May 2019

[x] http://oatuu.org/ accessed on 16 May 2019