BRICS labour: is it time for more class snuggle – or struggle – in an era of repression, austerity and worker militancy?

Across the world, trade unions are under unprecedented threat, as just witnessed in the United States where the Janus vs. AFSCME Supreme Court decision denudes an already weak labour movement of public sector power, for conservatives are aiming at “starving unions of funds and eventually disbanding them altogether.” Where, then, does organisational hope for working people lie?

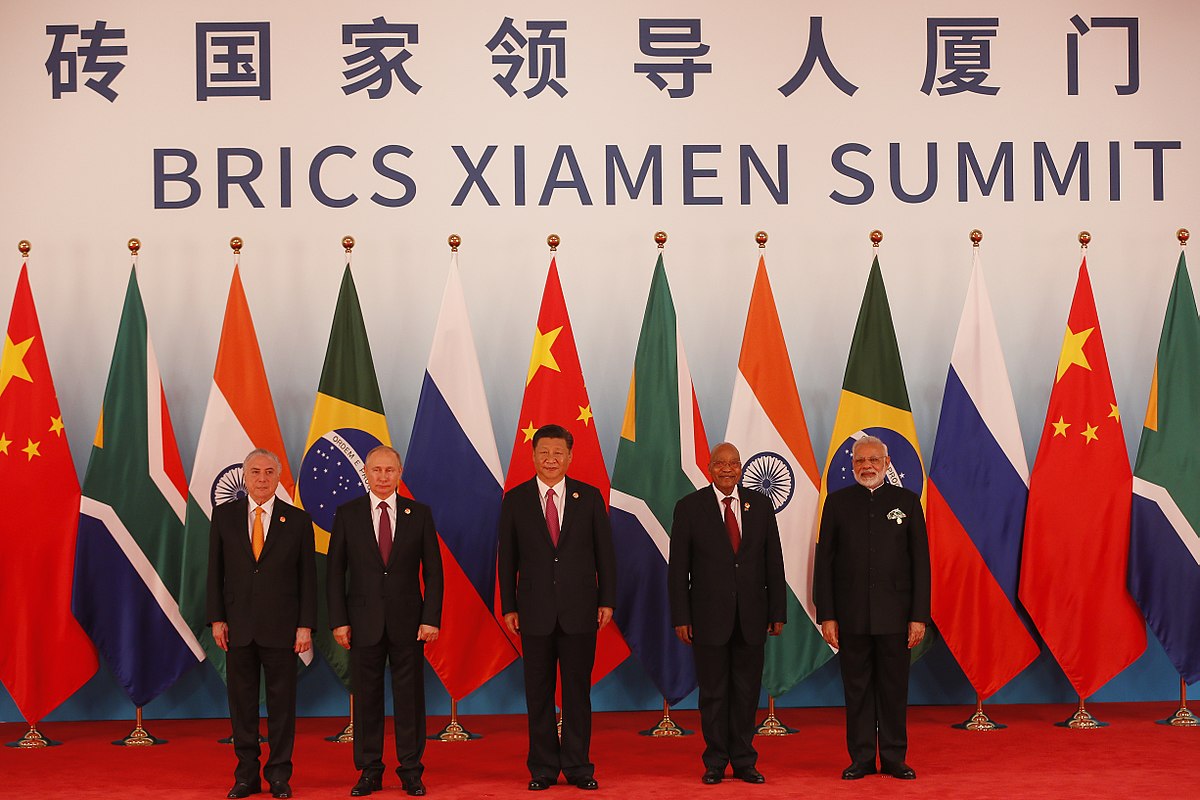

By far the world’s largest proletariat lies within the Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa (BRICS) bloc, whose state leaders meet in Johannesburg from 25-27 July and union officials gather in Durban the following weekend. Since 2012, the BRICS Trade Union Forum (BTUF) has attempted to traverse extremely difficult terrain, using an ever-changing roadmap.

Unfortunately, it is becoming obvious that along this path, BTUF leaders suffer a well-known problem: signalling to the left while driving the vehicle towards the right, as ground underneath the vehicle keeps shifting. For the BTUF to reach the desired location would require major adjustments in navigation, new passengers and very different manoeuvres.

Overall, BTUF membership is uneven across the BRICS’ working classes. The absolute size of trade union membership and density (i.e. the percent of the workforce unionised) vary, with China’s high numbers reflecting workers’ often frustrating ‘company union’ status:

- China: 240 million; 90 percent of workforce

- India: 87 million; 33 percent of workforce

- Russia: 24 million; 32 percent of workforce

- South Africa: 3.3 million; 30 percent of workforce

- Brazil: 17 million; 17 percent of workforce

South African BTUF affiliates are the Congress of South Africa Trade Unions (COSATU), allied with the ruling African National Congress (ANC) since the 1980s, with 1.7 million members; the traditionally most conservative (and historically white) Federation of Democratic Unions of South Africa (FEDUSA), with 700,000; and the National Council of Trade Unions (NACTU), which has radical pan-Africanist rhetoric but suffers substantial internal strife, with 260,000.

Membership figures ebb and flow. Aside from FEDUSA, which won back a public sector union last year, all have lost support. After the traumatic 2012 Marikana Massacre of 34 Lonmin platinum mineworkers who were on a wildcat strike, COSATU’s National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) surrendered much of its membership (down from 300,000 to 187,000) to the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (250,000 workers).

Even if greatly divided and weakened, South Africa probably hosts the most advanced and coherent of the BRICS union federation affiliates, and certainly boasts the most militant proletariat. Yet due to internal rivalry, the BTUF specifically excludes the South Africa Federation of Trade Unions (SAFTU) and its 680,000 members. SAFTU’s formation last year, after COSATU’s leader Zwelinzima Vavi and the 350,000-strong National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) were expelled, followed by the Food and Allied Workers Union (with 130,000 members) and a few others. The reason was SAFTU’s much stronger opposition to ANC neoliberalism and state corruption than COSATU’s loyalist members, at the time led by NUM.

SAFTU is excluded from the BTUF on spurious grounds: it has not been admitted to the National Economic Development and Labour Council (NEDLAC), a corporatist institution which critics argue is a ‘toy telephone,’ often irrelevant. As COSATU itself warned in 2016,

Government continues to boycott and undermine NEDLAC by sending junior bureaucrats with no decision making powers, while big business continues to condescendingly treat NEDLAC as a platform, where they think that they can go make presentations and not engage. We will shut down NEDLAC if these social partners keep undermining and undercutting it in this manner.

The boycott of SAFTU – especially of its leader Vavi and SAFTU’s metalworkers union (South Africa’s largest by far) led by Irvin Jim – shifts the BTUF ideological orientation much more to the centre. As a result, the BTUF is likely to maintain its status quo approach, no matter how dangerous this is for members, societies and the environment.

That route forward is merely continuation of predictable annual meetings in which trade unionists endorse the business-as-usual BRICS agenda, even while huge changes are underway in geopolitics, economics and environment – nearly all of which undermine labour, the broader society and ecology.

A different route would be to confront these contradictions head on, and locate greater shopfloor and grassroots unity. On 21-22 July , the weekend before the BTUF meeting and just before the BRICS leaders’ summit, SAFTU will gather thousands of its members plus civil society allies for a Workers’ Summit, which will more clearly spell out major policy and political differences with the other federations.

For example, in April, SAFTU put tens of thousands of workers on the streets against a proposed minimum wage – one strongly supported by the other three federations but which ranges between just US $0.80-US $1.50/hour, i.e., “paltry” according to Vavi. (The realistic poverty line is US $110/person/month.) However, there are occasionally signs of potential unity amongst left-leaning trade unions.

Such shopfloor resistance was witnessed when in mid-June, tens of thousands of NUM mineworkers and NUMSA metalworkers at the parastatal electricity supplier Eskom engaged in wildcat protests – allegedly using intimidation and ‘sabotage’ – sufficient to create a rolling national blackout. The unions’ objective was to discredit Eskom’s zero percent wage offer (the inflation rate is 4.5 percent), and they immediately succeeded in gaining a new offer above 6.5 percent. South Africa’s capitalist class was visibly unnerved by this show of strength, a precedent that might even lead to formal institutional NUM-NUMSA reconciliation, as NUM’s more critical leaders won greatly increased power at their recent electoral convention.

Moreover, NUM is now threatening to end electoral support for the ANC and transfer it to the South Africa Communist Party (SACP), a party itself debating whether to enter the 2019 election probably as a pressure point to make South Africa president and ANC leader Cyril Ramaphosa more amenable to its demands. The SACP already has several cabinet positions, yet core ANC policies are still neoliberal. (Recent exceptions include free tertiary education won through intense student battles, land “expropriation without compensation” – so far more rhetorical than real – and a National Health Insurance plan that appears perpetually underfunded.)

BTUF labour remains repressed, super-exploited but unevenly militant

In contrast to such rising militancy, also witnessed in massive recent truck-driver strikes in Brazil and China, the BTUF’s annual efforts are mostly aimed at social dialogue: promoting state-capital-labour tripartism in areas of common concern with BRICS leaders and the BRICS Business Council. But whether in Russia (2012), South Africa (2013), Brazil (2014), Russia (2015), India (2016) or China (2017), these efforts have not been successful.

The BTUF will meet on July 27-28 on the sidelines of the BRICS labour ministers’ Durban meeting, not at the Johannesburg leaders’ summit. The BTUF acknowledges lack of agency: “The Government of the Republic of South Africa has determined the time and venues of events with the participation of trade unions under the South African presidency in BRICS.”

Over six years, the BTUF has made reform proposals in the fields of global trade, finance, investment, climate and geopolitics, all areas in which workers and the rest of the world had hoped BRICS leaders might provide a genuine alternative to Western imperialism. Instead, the BRICS amplify neoliberal and anti-Southern multilateral perspectives, as argued below.

This is also apparent on home turf, for in some BRICS countries, the labour movement is extremely weak, e.g. China, which is characterised by state control, lack of autonomy, migrant labour discrimination, low wages and wildcat strikes (often harshly repressed). Conditions are worsening due to new technologies and to fewer freedoms to organise.

In the current International Trade Union Congress Global Rights Index, South Africa is in the second rank of countries where workers have won basic rights (i.e., among the world’s best 38), a decline from 2014 when it was in the highest group, alongside European social democracies. Next is Russia, in the third rank of countries, i.e., facing “regular violations of rights,” followed by Brazil in the fourth rank, with its “systematic violations.” The worst group – including China and India – are labelled as countries with “no guarantee of rights.”

One result is a relatively low level of absolute wages in the BRICS, illustrated within a sectoral case study: the textile industry. In 2011, South African textile workers were paid €3.8/hour, compared to €2.8 in Brazil, €0.8 in coastal China, €0.7 in India and €0.5 in inland China (the average wage in rich countries was €16.8/hour, but lower still are prevailing wages in places with vast labour reserves such as Vietnam and Bangladesh, at €0.3/hour).

Profits soar up the value chain, to the copyright owners and brand managers usually in the Global North, for as the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) remarks, “Even in a simple jacket, physical components, including labour, fabric, lining, buttons, sleeve heads, shoulder pads, labels and hangtags, account for only 9 percent of the price; the remaining 91 percent of the value is for intangible assets, including a wide range of services such as retail, logistics, banking and marketing.”

In other words, within a complex world division of labour characterised by global supply chains, the power of corporations controlling upstream value-chain components means that both BRICS and hinterland economies continue to suffer from super-exploitative processes: a wage rate that is often lower than the cost of reproducing labour-power.

As an example, South Africa’s Bantustan system was typical of the migrant labour relations that left caring for children, sick workers and the retired as a task for women in far-off settings, with little or no state support. This form of internal migrancy has usually emerged because it is extremely profitable, insofar as the employer does not bear the full cost of social reproduction. Such a system characterises most labour on the east coast of China, as well as sites like Marikana where mineworkers killed in 2012 were all migrants.

As a result of low wages paid to the majority of BRICS workers, labour’s input into gross domestic product (GDP) is relatively low. In most of the five (except South Africa), the recent period (2011-15) has witnessed a deterioration of the contribution of labour to GDP, according to UNDESA. Fixed capital investments that would raise labour productivity have been weak. Instead of incoming Foreign Direct Investment taking advantage of wage differentials, recent years witnessed much less capital-deepening investment.

One additional factor in labour productivity is worker militancy. One way to measure business-labour relations is the World Economic Forum (WEF) annual listing – based on polling 14,000 business executives from 137 economies – of shopfloor collaboration on a spectrum from most “confrontational” to most “cooperative.” In the 2017-18 Global Competitiveness Report, three of the BRICS – South Africa, Brazil and Russia – rated amongst the most confrontational third of the world’s national workforces.

Indeed, South Africa has ranked as having the world’s most militant proletariat since 2012, the year of the Marikana Massacre. The other two BRICS, India and China, are measured as having amongst the world’s more cooperative half of national workforces.

Country WEF militancy rank

- South Africa: 1

- Brazil: 32

- Russia: 48

- India: 82

- China: 88

Of course, the supposed average-level “cooperation” in the two largest BRICS may disguise intense pockets of labour militancy: in China there are several thousand illegal wildcat strikes per year, and in India in September 2016 there was a national strike of an estimated 180 million workers, the largest in world history.

Workers demand insourcing and a 4th Industrial Counter-Revolution

There is extreme variability in these BRICS labour experiences, resulting in unevenness and diversity of trade unions and federations. Still, universal trends are bringing BRICS workers into closer alignment, especially worsening casualisation and the 4th Industrial Revolution’s technological displacement of workers, as well as growing surveillance and privacy threats.

The 4th Industrial Revolution – conjoining cyber-technology, robotics, Artificial Intelligence, nanotechnology, biotechnology, etc – is a major theme in the 2018 BRICS summit. Official rhetoric has downplayed the likelihood of vast service sector unemployment, intensified social engineering such as China’s ‘social credit,’ or technological disasters.

In their official BTUF statements, the trade unions asked leaders to assist in the “de-monopolisation of the world market of software and IT-equipment, internet infrastructure management” (2016). This was based upon a valid critique of tech-corporate power, and was especially appropriate in India from where the resolution emanated. In 2017, however, “We appeal to the BRICS governments to seize the opportunities brought by the new round of industrial revolution and the digital economy” – but the BTUF failed to identify the many associated dangers. [[i]]

Against these trends, resistance to surveillance, robotisation and casualisation is not impossible. In South Africa there was an outcry by COSATU’s banking union the South African Society of Bank officials in 2018 against a major bank (Nedbank) for its planned replacement of 3000 workers with 260 robots.

More successful were campaigns in 2015 for the ‘insourcing’ of thousands of university workforces across the country, with a consequent rise in wages by a factor of two to four. However, the South African labour movement’s consistent demands to ban outsourcing in all sectors have been rejected by the ANC, and workers also lost campaigns against the introduction a sub-minimum youth wage in 2015, and against new labour legislation which includes a weakening of unions’ ability to call strikes.

The most important legal cornerstone of the 4th Industrial Revolution is corporate intellectual property, and destruction of these commercial rights applied to essential medicines was also the objective of South African workers during the early 2000s, in the case of Big Pharma’s monopoly control of AIDS drugs. Just as stigmatisation of HIV+ South Africans was peaking, Vavi and COSATU trade unionists formed a courageous alliance with the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC), demanding free medicines for more than five million affected people.

Although this campaign fatally soured relations with then-president Thabo Mbeki, an AIDS denialist, international allies joined TAC and COSATU to win a Trade Related Intellectual Property System exemption in 2001. As the medicines then became free by virtue of generic companies’ provision, via South African state health clinics, life expectancy rose from 52 in 2004 to 64 over the subsequent dozen years.

And in a battle against President Jacob Zuma lasting through most of the 2010s, COSATU (along with the Opposition to Urban Tolling Alliance) undermined state surveillance capacity and Public Private Partnerships – both also crucial to the 4th Industrial Revolution – with successful activism against e-tolling on Johannesburg-area highways.

In campaigns that have not yet been won, trade unions have also worked closely with the Right2Know movement, demanding free data and airtime so as to achieve the right to communicate, and opposing surveillance and Big Data social control. R2K welcomed COSATU’s crucial support against Zuma, to continually derail the so-called secrecy bill (“Protection of State Information” bill), which would have hampered whistle-blowing.

At the time, in 2011, the unions also strongly opposed the commodification of information, lack of transparency, and other threats associated with the emerging 4th Industrial Revolution. Vavi endorsed the 1955 Freedom Charter: “The law shall guarantee to all their right to speak, to organise, to meet together, to publish, to preach, to worship and to educate their children… All the cultural treasures of mankind shall be open to all, by free exchange of books, ideas and contact with other lands.”

All of this represents a 4th Industrial Counter-Revolution, in which technology (e.g. AIDS medicines) is appropriated as part of the world commons, and destructive Big Data and surveillance techniques are regulated or prohibited, bottom up. These are some of the most encouraging signs of counter-power. But within the BRICS, when it comes to discussions about the dangers of outsourcing and 4th Industrial Revolution, such signals are muffled to the point of silence.

Indeed, when trying to promote workers interests here and in nearly all other crucial socio-economic battles, the record of BTUF advocacy by national trade union leadership in the BRICS countries reveals many more disappointments than successes.

Trade union forum advocacy

In 2015, at its most expansive deliberation (at Ufa in Russia), the BTUF expressed ambitious expectations that BRICS leaders would address the world’s problems:

BRICS is an emerging structure of the new global management. Its flexible mandate allows the most dynamic economies of the world to consider a much broader range of issues than, for example, in the UN Security Council, and to find answers to many economic and environmental challenges. Decisions adopted by BRICS have a multiplier effect because the key states, which have joined it are in a position to translate solutions from BRICS into deliberations of other leading international agencies. BRICS countries are brought closer together by their consistent joint efforts in favour of reforming the international monetary and financial system.

But the question today, especially after right-wing forces have ascended to power in so many countries, is whether ‘new global management’ is any different than the old. To explore that question, consider the BTUF’s 2012-17 statements about its agenda, grouped into seven categories: institutional development; participation; vision; trade reform and regulation of transnational corporate investment; multilateral financial reform and innovation; climate change and environmental protection; and geopolitics.

In each case below, the most explicit advocacy statements are provided (in quotation marks with date of statement in parenthesis) followed by a preliminary assessment of results.

Institutional development

The BTUF in 2012 “declared the setting-up of a BRICS Trade Union Forum” and has followed through each year with a meeting, discussions and a declaration. “Our representation in the BRICS Trade Union Forum will be broad, pluralistic, democratic and inclusive of working men and women of our nations” (2014). “We also aim at identifying common programs and activities that build on each other’s strengths and virtues, with research and policy cooperation as a key element of that effort” (2014).

Though representivity is obviously in dispute given the conflicts especially involving BTUF member federations from China, India and South Africa (in relation to other workers not members of those federations), the objective of establishing the BTUF has been largely achieved. However, the BTUF could obviously be much better empowered for participation in BRICS summits, could generate alliances with other actors, and could establish the basis for genuine solidarity (e.g. when workers and citizens fight the same BRICS firm), in order to avoid the perception of a talk-shop. The need for research and policy coordination appears to have only begun; given that with perhaps one exception (Rio-based Instituto Brasileiro de Analises Sociais e Economicas), BRICS think tanks are hostile to organised labour’s interests.

Participation

The BTUF has made a consistent request to the BRICS leaders to “include the issue of Social Dialogue and of cooperation with Trade Unions” (2012), including through “national and global tripartite dialogue structures” (2013). The BRICS leaders should recognise the BTUF “as an institutional space within the BRICS official structure. We express therefore our expectation to have the same treatment as the Business Council, having our conference as part of the official program” and “be represented in the various task teams” (2014). “The model of interaction in the social triangle trade unions/business community/government structure has long proved its effectiveness at the national level in each BRICS country, and must find its logical extension into BRICS institutions” (2015). “We consider formal recognition of BRICS Trade Union Forum on an equal basis with BRICS Business Council as one of our priority objectives” (2016). “We appeal to the BRICS countries to improve the BRICS cooperation mechanism, grant the BRICS Trade Union Forum a status on par with the BRICS Business Council…” (2017).

The attempt at reaching formal tripartite status has not been achieved, although there are efforts by BRICS Labour and Employment Ministers to at least briefly discuss matters of participation with the BTUF, and a BRICS Working Group on Employment has been established. The problem lies not only in BRICS mechanisms, but in each country. For example, most Indian trade unions boycotted 2016 BTUF proceedings on grounds of differences with the Modi government, just a few weeks after the historic September strike, which witnessed 180 million labourers refusing to work.

The BRICS countries with the strongest social dialogue structures and collaboration between ruling party and trade unions are Brazil and South Africa. The tough Brazilian trade union critique of Temer’s regime (as a corruption-riddled constitutional coup) reflects breakdowns in the former, especially after the jailing of Lula on an apparent corruption frame-up in 2018. South Africa’s NEDLAC has not functioned well in recent years, as noted above.

Further, the BTUF requested that, “BRICS trade unions should be represented on the BRICS bank’s highest decision-making body” (2013). This request was ignored in the Fortaleza construction of the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB), which resulted in a small (ten-person) management and directorship – all male – without any high-profile voices that represent the interests of poor and working-class people, or the environment. One result, in South Africa, is that the first two BRICS NDB loan offers promote privatised electricity supply through the corrupt Eskom parastatal agency, and port expansion through the corrupt Transnet parastatal.

Vision

The BTUF vision statements repeatedly stress the need to promote:

- “growth and sustainable development, along with food, and energy security, Green Economy in the context of Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication” (2012);

- “attainment of the MDGs” (2012);

- “Decent Work, boost employment, secure a universal social protection floor and promote the transition from the informal to the formal economy” (2013);

- “industrialisation, environmental justice and human progress for equitable and fair growth models” (2013);

- “peace, security, human rights and global sustainable development” (2013);

- “social protection for young people and women” (2013);

- the distribution of wealth; as well as food and energy security for our nations, and enhance joint efforts of BRICS countries in the studies and research on labour market” (2013);

- “the need for accelerated growth and sustainable development, together with the promotion of food and energy security, poverty eradication, the fight against hunger and malnutrition, as well as measures for job creation” (2014);

- “respect for local communities, sustainable use of natural resources and the search for a low carbon, clean energy matrix” (2014);

- “accelerated growth and sustainable development, together with the promotion of food and energy security, poverty eradication, the fight against hunger and malnutrition, as well as measures for job creation needed to improve living standards” (2014);

- “promotion and inclusion of women and youth in the labour market, ensuring the protection of their labour rights, must be at the centre of employment policies” (2014);

- “trade unions are an effective force in defending democracy and in the fight for justice and ecologically sustainable future” (2015);

- “the BRICS countries should take a head start to focus the efforts of the peoples and States on technological breakthroughs in the interests of all strata of society in our countries” (2015);

- “promote agriculture and agro based industry” (2016);

- “de-monopolisation of the world market of software and IT-equipment, internet infrastructure management” (2016);

- “vigorously implement the proposals in the Recommendation No.204 of International Labour Organisation (ILO) on formalising informal sector” (2016);

- “make decent work an active ingredient in employment generation especially targeting women, youth, marginalised and other disadvantaged groups” (2016);

- “maintain and improve social security and social protection systems” (2016);

- “we demand the BRICS Governments vigorously implement [the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals] with the active participation of national trade unions so as to generate more employment, eradicate the wage gap in the existing jobs, and rectify all decent work deficits” (2016);

- “we strongly request the BRICS Governments to evolve an alternative developmental model which will be more people centric” (2016);

- “Foster the concept of a community of shared future for mankind and deliver robust, sustainable, balanced and inclusive growth in the global economy” (2017);

- “improve their labour policies, increase jobs, encourage innovation and entrepreneurship, raise financial input for vocational education and job training, establish an inclusive and efficient job training system, deepen cooperation with social partners, intensify efforts to provide employment and re-employment training for workers and enhance workers’ competency and adaptability” (2017).

These vision statements are all appropriate as minimal common desires for labour, but they lack the sense of a proper workers’ manifesto. The traditional goals of the working-class movement – socialisation of production and de-commodification of the reproduction of labour power – are not mentioned much less elaborated.

BTUF statements never draw explicitly on the constitutions and policy documents of the member federations, several of which are explicitly socialist. One such labour manifesto stands out, the earliest one, from the International Working Men’s Association: The Communist Manifesto. Such traditions of labour solidarity are vital for turning working-class values into practical cross-border collaboration. But it would be a quite extraordinary leap of ideological maturity for the BTUF to mention this tradition, one still too far to contemplate.

The big question remains whether these values can be implemented by BRICS governments, which are in all cases – rhetoric aside – quite explicitly hostile to the BTUF agenda. Several examples of this dilemma can be considered next, in the four categories of trade and corporate investment, multilateral finance, climate change and geopolitics.

Trade reform and regulation of transnational corporate investment

The BTUF argue that “policies should aim at supporting industrialisation” and BRICS leaders “should work with other developing countries towards the transformation of the world trade system” (2013). With respect to Foreign Direct Investment, the BTUF insists, “that all multinational companies comply with core labour standards, and do not exploit unequal conditions between countries” (2013). “The time has come to establish real control over large-sized multinational corporations operating on our territories and to subordinate their activities to development objectives” (2015). “We must give support to the deserving people outside BRICS who are suffering extreme conditions of exploitation” (2016). Moreover, “BRICS governments should respect ILO Labour Standards and Recommendations as important part of all Trade and Services Agreements and take special measures to promote decent work in global supply chains” (2016). Meeting last year in China, the BTUF (2017) asked leaders to “strengthen their unity” and “make joint efforts to fight against protectionist policies.”

Multilateral financial reform and innovation

The BTUF argue that the BRICS New Development Bank “should take a different form from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). It should primarily developmental in character” and be “solely owned by BRICS, publicly funded, decisions on consensus, promoting trade based on own currencies of its member countries, with a core focus on infrastructure and development in consultation” (2013). The NDB and Contingent Reserve Arrangement should be “fundamental tools for the effective transformation of the current international economic architecture… and bring benefits to workers and promote sustainable development” (2014).

The BTUF also aims to “stop the financial casino, but also to create mechanisms for taxing financial transactions, large fortunes and tax havens” (2014). NDB revenues should “be used to expand investment in the productive sector and infrastructure; in education, science and technology, training and professional qualification” (2014). The NDB should have “sovereign independence from the bankrupt Bretton Woods system” and “BRICS Governments should establish their own Rating agency and a Stock exchange… to influence world economy” (2014). “We expect that BRICS Governments will pursue more vigorously the reforming of the IMF and of the World Bank” (2015). “The BRICS countries should participate in global governance on behalf of developing countries” (2017).

Geopolitics

The BTUF demands, “that the BRICS agenda does not isolate regional and continental counterparts, and will work to advance the interests of the developing world in general” (2013). Further, the BTUF asked “Governments of BRICS countries to do their utmost to reduce political tension in the world, to ensure global security and stability, cessation of hostilities wherever they occur, to contribute to an active and unconditional application of the rules of international law” (2015).

Conclusion

The alternative approach to BRICS labour politics – based not on social dialogue but social power, based not on class snuggle but class struggle – entails, first, identifying as many other oppressed allies as possible (not simply gazing upwards in search of tripartite relationships which have proven so disappointing thus far). Making alliances with these social forces would expand the BTUF field of vision to more explicitly incorporate the interests of poor and working people, women, students and youth, environmentalists, the LGBTI community, and social movements across so many other issue areas.

(The BRICS counter-summits in Durban, Fortaleza, Goa and Xiamen had such “brics-from-below” relationships emerging, in contrast to government-sponsored BRICS Academic Forum, Civil BRICS and Youth BRICS events, which have been essentially uncritical.)

As discussed above, the best example of brics-from-below dates back more than 15 years: the economic attack against Western pharmaceutical corporate patents by two governments – Brazil and India – subsequently aided by South African HIV+ activists in the TAC, COSATU and their allies. By opening a state-supported generic industry and ignoring international property rights, the Indians and Brazilians assisted progressive South Africans who overthrew the denialist AIDS policy adopted by former president Mbeki.

The combination of de-commodification and de-globalisation of capital, and the coalition between progressive governments and radical community activists was decisive. Can that same alignment be repeated, and can it serve as the basis for an entirely different approach to BRICS, fusing states and people in the public interest?

Regrettably, as the pages above showed, the BRICS have chosen the course of undergirding – not undermining – imperialist multilateral agencies (the World Trade Organisation, Bretton Woods institutions and the UN climate process) whose role in commodifying all aspects of life and globalising capital is disastrous for poor and working people, within the BRICS as well as for Africa.

What that means for BRICS in the years ahead, it is fair to predict, is more top-down scrambling within Africa, and more bottom-up resistance. Where African governments emerge that have more patriotic instincts, there will be scope for campaigning on matters of economic justice: e.g. against mining and petroleum extraction, illicit (and licit) financial flows, and illegitimate debt.

With the profits of so many Western firms in Africa hitting new lows and their share value nearly wiped out (e.g. the 2011-15 cases of Lonmin, Anglo and Glencore, which each lost more than 85 percent of value), there are precedents for what BRICS firms now may find logical: yet more extreme metabolisms of extraction and more desperation gambits to keep BRICS-friendly regimes in power, at the expense of the reproductive needs of society and nature.

But resistance is already evident. For example, the BRICS People’s Forum counter-summit in Goa in October 2016 included a call by Indian social movements and labour for a People’s Forum, one repeated in September 2017 in Hong Kong.

Further alliances of a horizontal nature are also obvious, not only with civil society – especially trade unions – and not only reaching out far into Africa where BRICS has had a destructive or constructive impact, but also with other trade unions across the world.

To illustrate the hopes for such solidarity, International Trade Union Congress President João Felício argued at a July 2015 Ufa BTUF plenary that “The BRICS have an opportunity to establish a de facto different political discussion on the direction of the economy, finance and the world of work… The new financial institutions of the BRICS cannot share the neoliberal rationale of the Troika, which puts the interests of big business above the rights of workers and the well-being of citizens in their countries.”

But that opportunity was lost – as witnessed by the three choices to reform multilateralism made in December 2015 – and will probably not arise again. Indeed it is ever more likely with the turn to Trump, with economic conditions rapidly worsening, and with growing official hostility to trade unions in especially Brazil, India and South Africa, that the interests of big business will prevail even more in the years immediately ahead.

Felício remarked, “It is necessary to put solidarity before austerity, rights before profits, democracy before the market. If the BRICS succeed in becoming at least part of this process, it will create a political and economic frame of reference for other bodies, such as the G20, the IMF or the World Bank and even national governments.”

The likelihood that the BRICS leaders will oppose these values has been demonstrated above. Hence, Felício concluded, “politicising the debate was the only way to combat the deepening of inequality, fight for better salaries, promote collective bargaining and reverse the downward trend in unionisation rates.”

Further politicisation is evidently necessary. Indeed, the potential for fighting back – for class struggle instead of class snuggle – is enormous.

In the 2018 host city, Johannesburg, the week before the BRICS elites’ summit, SAFTU has called for a Workers’ Summit, at which the main grievances of the BRICS working class will again be aired – and the inability of the elites to solve these problems will again be obvious.

* Patrick Bond is professor of political economy at Witwatersrand and honorary professor of development studies at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

[i] At the same time, a Fuzhou Initiative statement by academics and civil society reflected how much faith BRICS-aligned ‘watchdogs’ place in state surveillance, social engineering, and other threats to privacy: “BRICS countries should also increase cooperation in cyber security and promote the development of Internet technologies and the governance of cyberspace globally.” Ominously, such intra-BRICS spymaster collaboration is already underway: http://www.dailypioneer.com/nation/chinese-nsa-meets-separately-with-co… accessed on 14 July 2018