Africa’s Great Lakes Region: The most democratically challenged?

Africa’s richest regions is said to host some of the most undemocratic governments in the continent where presidential palaces seem to have become private properties over which blood must be spilt if some strangers show signs of trespassing the perimeters. Is there any hope for this situation to change?

Despite being one of Africa’s richest regions in natural resources, Africa’s Great Lakes Region is said to host some of the most undemocratic governments in the continent. In most of these parts, presidential palaces seem to have become private properties over which blood must be spilt if some “strangers” show signs to “trespass” the perimeters. It indeed is a serious business here; majorities have not the power to decide whom they want and whom they do not. Only certain individuals from some “usual gangs” can run the show.

These people and their groups consider themselves to be professionals that invented the game; they know of no defeat, and cannot take it.

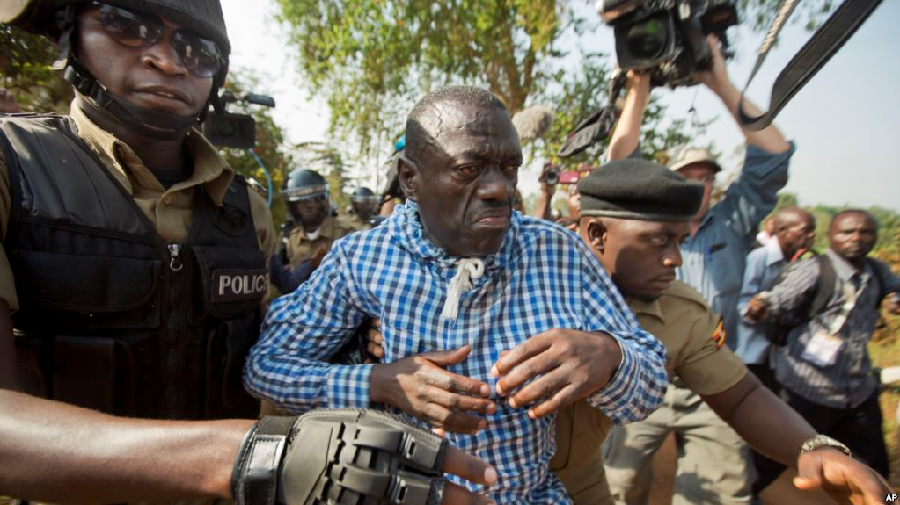

This region is seemingly the most dangerous place to be on the team that does not run the state house. It may be quite a struggle in other parts of the continent too, but here danger is mostly guaranteed. If you ask Kizza Besigye, Uganda’s strongest political opponent to President Yoweri Museveni, he could perhaps tell you how much time he had to spend with his family when he “rubbed shoulders” with his former boss and patient, until he decided to become his challenger, a move that came with a price to pay – frequent confinements. He has now probably had cuffs on his hands much more times than he has ever had his timepiece.

Museveni has been president of Uganda for three decades now since 1986 and has not given retirement a thought; in fact, he is amending the constitution to fit his desires of taking his presidency with him to grave. The 73-year-old president is seeking to serve a sixth term. The current laws would deny him eligibility to run for presidency, as it does not allow candidates above the age of 75. He clings to the idea that no one can replace him after more than 30 years in the position, and still believes that he has the chance to bring real changes into existence, but I doubt he will when he is senile. Astonishingly, he gets support from most of his party members in parliament, which led to the bill winning 315 votes with only 62 voting against.

Museveni is not the only figure of his character in the region. Rwanda’s Paul Kagame, who has been in power since 2000 following his predecessor’s resignation, has already secured his position after the constitutional amendment in 2015, which was meant to extend presidential terms. He too is said to have not spotted the “right handler” of the country’s reins. Opposition figures in the tiny East African country have been reported to suffer arrests while most living in exile which weakens their ability to launch strong opposition against Kagame. His critics and international communities say there is lack of inclusiveness and freedom is badly suppressed and that, in Rwanda, the enemy, just like most places in the region, is he who holds views different from the incumbent’s.

Reporters Without Boarders, an organisation that promotes and defends freedom of information and freedom of the press, sees Kagame as the enemy of freedom of expression based on the fact that in the last two decades, eight journalists have been killed or gone missing, 11 have been prisoned and 33 forced to seek refuge outside the country. Despite all that, Kagame is widely praised for his efforts to transform Rwanda’s economy and making it one of the least corrupt nations in sub-Saharan Africa. The amended constitution allows him to stay in power until 2034.

Another state in the region, Tanzania, has seen a long series of what are believed to be peaceful transitions of power. Yes, it is true that hardly any blood has been shed during its elections, but the opposition parties and media outlets with different views and opinions from those of the ruling party Chama cha Mapinduzi—CCM (Revolutionary Party) seem to be under threat of going extinct. A series of shocking events have been happening in this resource-rich country during previous governments and present. Just recently, on 7 September last year, one of Tanzania’s most outspoken member of parliament from the opposition Chama cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo—Chadema (The Party of Democracy and Development) and President of Tanzania Law Society (TLS), Tundu Lissu, was shot multiple times in an assassination attempt carried out by “unknown people” at his residence in Dodoma. His vehicle was showered with as many as 32 bullets whereby five bullets hit him in different parts of his body before assailants successfully fled the scene.

The learned politician has been fiercely critical towards President Magufuli’s government, and had been repeatedly arrested before the incident. Perpetrators have not been caught yet. Police are still “working on it”.

Another event featured a freelance journalist who reported with one of the country’s giant papers “Mwananchi” (Citizen), Azory Gwanda, who went missing after he was reportedly taken by four unidentified people in a white Toyota Land Cruiser on 21 November 2017, and raised nationwide concerns. The media in the country launched a campaign demanding the government to find him, but all the efforts bore no fruits.

This was not the first time journalists in Tanzania faced such brutality. On 5 January 2008, Said Kubenea, owner and investigative journalist of a weekly tabloid critic to the government, “Mwanahalisi”, was attacked with chemicals by “unknown people” while in his office in Dar es Salaam. Kubenea is currently an opposition member of parliament representing Ubungo Constituency.

Joseph Kabila, president of the region’s largest and most troubled nation, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), is already overstaying his welcome in the presidential palace despite nationwide outcry for him to let the country take a democratic course coveted by most Congolese people. Kabila, whose second term was due to end on 20 December 2016, is allegedly delaying the election to remain in power, a move that has led to protests and dozens of deaths. The nation’s electoral body announced that elections would not be held in 2016, until at least April 2018 as the number of voters was unknown. The people of Congo have rejected Kabila’s continuous stay in the state house until December 2018 as it violates the country’s constitution. Since 2016 hundreds of opposition leaders and supporters have been arrested for taking part in “outlawed” protests in the capital, Kinshasa, but people have not ceased to demand the “outdated: head of state to step down.

In 2015, Burundi’s Pierre Nkurunziza was controversially nominated by his party National Council for the Defense of Democracy–Forces for the Defense of Democracy for a third time in office, a move that was met with strong opposition from his political opponents and sparked two-month long protests demanding Nkurunziza to abandon his intention. At least 1000 people were reported to have died in the protests [and the violence that followed] and more than 400,000 fled the country. The president defied the public call to step down and the elections, which had been boycotted by most of other political parties, went ahead on 21 July 2015. The electoral commission announced that Nkurunziza had won the poll with 69.41 percent and was sworn in on 20 August 2015. More than 500 Burundian protesters were arrested with nearly 250 cases sent for prosecution. The 54-year-old politician is currently serving his “forced” third term as president of Burundi [and there are plans to amend the country’s constitution to theoretically allow him stay in power until 2034].

The region’s discovery of oil and gas with a number of mega infrastructural projects being put in place including DRC’s Grand Inga Hydroelectric Plant, a multi-billion dollar project expected to be the biggest hydropower producer in the world upon its completion, and East Africa’s standard gauge railway project could actually change the current image of the region only if democracy is existent.

The region can surely expect not so much to achieve if people’s rights are violated and hatred between the public and authorities worsen. Targeting journalists, activists and political opponents is not the pathway to walk on. Maintaining tight grips on power can only bring chaos and frustration amongst the people.

* Mweha Msemo writes from Tanzania and can be contacted at <[email protected]>