Chinua Achebe’s ten teachable lessons

Beyond the limitations of his personal history in the new classic ‘There Was A Country’, Achebe calls on everyone to rebuild an Africa that accommodates all irrespective of race, class, gender or religion.

‘… My father and his uncle formed the dialectic that I inherited.’ Achebe stated on page 13 of ‘There Was A Country’, his new instant classic. For those who do not know, a dialectic is the negation or contradiction between opposites (the thesis and the anti-thesis, negation or contradiction) that results in a synthesis (or negation of the negation) through a combination of the best in the thesis and the anti-thesis. The synthesis becomes the new thesis to be soon contradicted by a new anti-thesis in endless struggles between ideas (according to Hegel) or struggles between social classes (according to Marx) but the struggles are between cultural traditions in the case of Achebe:

Achebe’s father was raised as a devout Christian by his own uncle who was a titled practitioner of Odinani (Igbo religion). No Christian or Muslim would be tolerant enough to raise a family member in African traditional religion today. Most reviewers of Achebe’s book so far have missed the significance of this foundational thesis of Achebe in ‘There Was A Coutry’. Wole Soyinka corroborates this thesis, in ‘Of Africa’, where he identified the policies of exclusion and boundary enforcement as major threats to African tolerance and accommodation as exemplified by African religions that have never tried to conquer, enslave, convert or colonize non-believers.

In case readers unfamiliar with the metaphorical Igbo style of Achebe missed this riddle, he repeats the message on pages 18-19 and 56 where he talks about the significance of the celebratory arts of Mbari among the Igbo, the name that he gave to the literary club at the University College of Ibadan that he formed with Soyinka, Okigbo and Ulii Beier. It was in the town of Nekede where he went to live with his elder brother who was a teacher that he was introduced to this cultural performance by which the Igbo community came together, artists and commoners alike, to build a miniature house with every race, gender, class, and ethnicity represented and even with the spirits of the deceased accommodated with models of living generations without any discrimination. Achebe emphasizes that the inclusion of European characters in the sculptures was ‘a great tribute to the virtues of African tolerance and accommodation.’

The above is the central thesis of the whole book and part one of the book is an elaboration of this thesis with the example that the village mad man once walked up to his elementary school teacher who was giving a lesson about the geography of Britain under a mango tree, took the chalk from the teacher and wiped the black board, then proceeded to give a lesson about the history of the town, Ogidi, which was more relevant to the students. In Europe or North America, the teacher would have called the police to come and arrest the mad man as a threat but the teacher let him have his say as is expected in the radical democratic traditional culture of the Igbo where it is proudly asserted to this day that Ezebuilo or monarchy is enmity. Similarly, when Achebe abandoned his scholarship as a medical student and chose to major in English and theology, many parents today could have disowned him but his elder brother who was an engineer stepped up and paid his fees as an example in tolerance. Indirectly, Soyinka agrees in ‘Of Africa’ that this is proof that democracy is not alien to Africa contrary to the ideology of dictators suffering from what he called deliberate cataract, who used to say that Africans were not ripe for democracy, as if we were some kind of bananas, according to Abdulrahman Babu.

Parts two and three of the book focus on the Biafra war and represent the counter-thesis or contradiction of the original thesis of tolerance and accommodation as African virtues. Part four of the book presents the synthesis and the example of Nelson Mandela was used in the postscript to underscore this logical structure of the dialectical narrative in the book. Most reviewers glossed over this while presenting mere summaries or simply reacting emotionally to the excerpt in The Guardian condemning the Igbo genocide that cost more than three million lives. Unfortunately, too many people are running their mouths in knee-jerk reactions without even bothering to read the engaging book first with an open mind willing to learn from the great but humble teacher.

Since many of the okirika reviews (Okirika is the Igbo town after which trade in second-hand clothes was named and the trade was banned by the military government soon after the war presumably to crush the restarting of the Igbo commercial dominance in buying-and-selling, but the pretense was that it was demeaning for Nigerians to buy clothing discarded by Europeans, not knowing that even in Europe, lots of people rely on second hand clothes shops provided by charities like Oxfam) have already summarized the story, I will dwell here on the ten teachable lessons that Achebe was challenging our blind sociologists, political scientists and historians to explore further beyond the limitations of his personal history in ‘There Was A Country’:

1) Biafra was the foundational genocide in post-colonial Africa and the script is still playing from time to time across Africa perhaps because we have never really learned the lessons of Biafra as Herbert Ekwe-Ekwe has harped in ‘Biafra Revisited’. Genocide is not a part of our culture and the mass killing of millions of people is an absolute abomination that has no justification in any culture. Such atrocities were introduced to Africa following the hundreds of years of the enslavement of Africans by Arabs and then by Europeans before being formalized as gunboat diplomacy during the 100 years of colonialism, before finally being handed over to post-colonial dictatorships that were trained and armed by foreigners and egged on to wage proxy wars against fellow Africans to guarantee access to resources and wealth. Achebe could have made this lesson sharper by directly calling for reparations for slavery, colonialism and the Igbo genocide as Soyinka suggested on page 54 of his new text, ‘Of Africa’.

2) Achebe’s book is delivered in bite-sized passages of text rather than in intimidating long chapters perhaps to attract and keep the attention of the Nollywood (Nigerian films) generation and persuade them to shine their eyes away from media screens and ginger their swagger with valuable history lessons in a country where a democratically elected former military dictator disdainfully banned the teaching of history in schools but no one defied such a bizarre phobia about history lessons particularly following a traumatic bloodbath that would make the teaching of history mandatory. Achebe has come to the rescue and the amazing thing is that quite a few ‘intellectuals’ are feigning annoyance at him for revisiting the national shame and pointing out valuable lessons. For instance, while claiming that he is yet to read the book after glancing at a Kindle copy of his friend, the poet, Odia Ofeimum, reacted emotionally by telling journalists that the leaders of Biafra should be the ones to be tried in Nuremberg-style courts for the genocide that resulted following the policy of ‘starvation as a legitimate weapon of war’ cruelly canvassed by the hero of Ofeimum, Obafemi Awolowo, the then finance minister and vice chairman of the federal executive council. In 1983, Awolowo was reported as defending the same obnoxious policy of ‘all is fair in warfare’ and starvation as a legitimate weapon of war, 13 years after the Biafra war. Today in 2012 the disciples of Awolowo continue to defend his shocking statements instead of learning from the Igbo proverb that says that when a vulture farted and told his children to applaud, they said, Tufiakwa (or Never) because we do not applaud evil but without disowning their father for as Achebe put it in ‘Vultures’, one of the poems that illustrate the book, ‘…in the very germ of that kindred love is lodged the perpetuity of evil’, p. 205. Ofeimum who was the personal secretary of Awolowo had earlier reviewed Achebe’s 1983 ‘The Trouble With Nigeria’ under the title, ‘The Trouble With Achebe’ and unfairly suggested that Achebe obsessed too much with the Igbo question in Nigeria mainly because of Achebe’s critique of Awolowo which was milder compared to Achebe’s critique of his fellow Igbo, Azikiwe.

3) ‘There Was a Country’ develops in cyclical or fractal patterns with self-similarity, infinity, recursion, fractional dimensions, and non-lineal geometry in the sections found in the four parts of the book rather than follow a chronological historical timeline in the structuration of the narratives. This elliptical style is the hallmark of Wole Soyinka (although Achebe delivers with clarity except in the war-time poems that he probably did not want the Biafran Intelligence to understand or he could have risked being arrested, like Professor Ikenna Nzimiro who dared to argue with a police officer and like Achebe’s cousin who unwisely shared his opinion with fellow soldiers that if they did not have the weapons to fight with they should give up. Soyinka probably adopted the cryptic style to conceal his acerbic critique from the moronic goons of the crypt of the title of his prison poems, ‘A Shuttle in the Crypt’, a cryptic style that distinguished his pre-detention lucidity in ‘The Lion and the Jewel’ from his post-detention complexities like ‘Season of Anomy’). This elliptical style is consistent with the conclusion in ‘African Fractals’ by Ron Eglash who saw it as the characteristic of the majority of designs in African culture in contrast to European designs that favour straight grids in conformity with the principles of Rene Descartes for the purposes of easier conquest, control and mastery. In the hands of Achebe, this fractal presentation of the complex story helps the reader to remain alert throughout the book and compels the reader to follow the story non-stop as scenes of chaos are interwoven with hilarious humour, just as the war was experienced with love and laughter and not exclusively with tears and mourning.

4) The role of intellectuals as war mongers while other intellectuals struggled for hegemony or moral and intellectual leadership was highlighted by Achebe over and over again. Godfrey Chege recently asserted in an essay, ‘Africa’s Murderous Professors’, that educated Africans have played ignoble roles directly or indirectly in supporting genocide across the continent – a point that Soyinka made earlier in his detention memoir, ‘The Man Died’ - but this is also true of European intellectuals in Africa and in Europe, according to Achebe. ‘There Was A Country’ commends the bravery of Wole Soyinka who risked his life by opposing the genocidal war and critiques Ali Mazrui for condemning the poet, Chris Okigbo, who gave his life trying to save those that faced the threat of genocide. Achebe also critiqued the cavalier account of Emmanuel Ifeajuna who submitted a manuscript to Achebe and Okigbo for publication during the war in which he appeared to gloat over the assassination of Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa in the first coup that led to the second coup and the pogroms that led to the war. Nevertheless, Achebe gives enough indication that it was regrettable that Ifeajuna and Victor Banjo, among others, were executed by Ojukwu following the distrust brought on by the siege mentality of losing battles without adequate equipments, or simply because Banjo was a poor speech writer. He also deplored the attack on an Italian oilrig in Kwale resulting in the killing of some and the taking of 18 hostages that cost Biafra much of the goodwill it enjoyed internationally. Although Achebe adored Okigbo, he mildly rebuked the poet for being obsessed with food from high school days when he would devise ways to get extra food that was apparently wasted, to his waking up of Achebe’s cook early in the morning to cook a secret recipe according to his specification and to his absent-minded consumption of the special cravings of Achebe’s pregnant wife that he ordered to be sent to his own hotel room instead, causing Achebe’s three-year-old son to attack him playfully only to later cry, ‘Father, do not let him die’, when news came that Major Okigbo died in the war front near the place that inspired his poetry. Although Achebe did not say so, that much gluttony could have been responsible for the mystery that the gifted poet and star athlete was never a good student academically, according to Obi Nwakanma, in his biography, ‘Okigbo: Thirsting for Sunlight’, in which it was reported that the poet used to steal crates of beer from one of the professors during his college days.

5) Moreover, Achebe expressed disgust at Chief Obafemi Awolowo for repeatedly boasting that he stopped international relief organizations from sending food and medicine to Biafra because ‘All is fair in war and starvation is a legitimate weapon of war.’ As Duro Onabule rightly stated in his column in The Sun Newspaper, Awolowo should not have continued to defend this statement that Achebe rightly dubbed a diabolic policy when neither Gowon nor the other genocidal military dictators that Awolowo served dared to openly canvass such an obnoxious war crime as a justifiable policy. As an intellectual, Awolowo should have known better and could have used his influence in the military government to push for a more humane ending of the war and the rehabilitation of the Igbo. Rather he imposed a vengeful policy of stripping the Igbo of their savings in exchange for a miserly 20 pounds per family head at the end of the war and proceeded to indigenize shares in multinational companies at the same time to exclude the Igbo who were feared as the dominant ethnic group in all aspects of Nigerian economy and society before the war. It is disappointing that some disciples of Awolowo are continuing to defend the same wicked stance today instead of agreeing with Achebe that any policy designed to kill three million Africans by fellow Africans and expropriate their wealth is indeed diabolical and indefensible. It is not too late for the followers of Awolowo to distance themselves from that shameful belligerence against an innocent people who had nothing against them. Without mentioning Biafra, Soyinka supports such dissociation in ‘Of Africa’ by stating that the admission of sadism on the part of some does not condemn a whole continent as sadists.

6) Achebe repeatedly described Awolowo as a brilliant leader who united the Yoruba politically and he also described the Sarduana of Sokoto as a brilliant politician who united the Northern region politically. He also expressed admiration for Aminu Kano for not joining Anthony Enahoro in threatening to crush Biafra during the peace talks in Uganda. By contrast, he was almost disdainful towards Azikiwe who never received a direct praise in the book but was slightly ridiculed for telling his supporters that when the British Governor General told him that he wanted to stay on after Nigeria’s independence, Zik told him that he was welcome to stay as long as he wanted. Zik was directly critiqued for saying that Nigeria got independence on a platter of gold and Achebe likened it to the head of John the Baptist. Readers of ‘The Trouble With Nigeria’ will know that Achebe has a long resentment against Zik for what he called the ‘abandonment syndrome’ of never seeing anything through. Even when the Zik Group of Newspapers was praised for writing in a plain style that the Latin-loving colonial elite ridiculed but the masses loved, a style that Achebe was to adopt in his own writing but which he attributes to his experience drafting radio broadcasts at Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation, the praise appeared to be for the editorial board led by Anthony Enahoro rather than for Zik personally. In ‘There Was A Country’, Achebe reveals the source of this seething resentment – ‘Azikiwe Withdraws Support For Biafra’ but Achebe makes this appear understandable in the context in which an ‘Aristocrat’ like General Ojukwu did not consult or take advice from Zik of Africa while the formula for peace, reconstruction and rehabilitation that Zik proclaimed at Oxford University was rejected as ‘unworkable’ by Nigeria only to become the model for UN interventions around the world today.

7) Achebe acknowledged the support of international media which rallied to expose the atrocities imposed on people in Biafra, mentioned an American student who set himself ablaze to attract the attention of a silent UN; Kurt Vonnegut, an American scholar, cried for days after his visit before writing ‘Biafra: A People Betrayed’; Auberon Waugh wrote a book lamenting the complicity of Britain in the genocide following a trip to Biafra and named his newborn baby Biafra Waugh; European missionaries who volunteered to defy the embargo and fly relief to Biafra, the few African countries that formally recognized Biafra and performers like John Lennon and Jimi Hendrix who played tribute concerts to support relief efforts. However, the international community was critiqued for supporting the genocidal war. Britain and The Soviet Union (cold-war enemies) supplied weapons to Nigeria and ensured that more small arms were used against Biafra during the 30 months war than were used in the five years of World War II. Achebe implies that the Nigerian government should take responsibility for allowing this to happen to its people and should endow a huge reparations fund for the survivors of Biafra. The UK and government of Russia (on behalf of the Soviet Union) should equally endow huge reparations funds to help heal the wounds of the Biafra genocide that they helped to engineer. No matter how big the reparations funds turn out to be, they would still be mere tokens of atonement that may help with healing the psychological scars that Nigeria and Africa continue to suffer from. No Nigerian group would be deprived of anything when the wrongs done to the Easterners are recognized and reparations offered as Soyinka has been demanding since the end of the war.

8) The then British Prime Minister Harold Wilson of the Labour Party responded to the accusation that Britain was supporting the genocide being committed by religious fundamentalists by stating that the Nigerian army was 70 percent Christian just like the predominantly Christian people of Biafra. He also argued that General Gowon, as well as his field commanders, Olusegun Obasanjo (who bragged that he celebrated the shooting down, on his order, of a plane carrying relief supplies for the starving people during the war) and Benjamin Adekunle (who boasted that he did not give a damn if the Igbo got not a single bite of food and that he shot at everything that moved and even at things that did not move), and Theophilius Y. Danjuma, were all Christians. Such dishonesty is startling given that Christians have battled and killed Christians for millennia, just like Muslims. But for those who do not know, religious ‘fundamentalism’ first emerged among self-proclaimed ‘Fundamentalist Christians’ in the US who advanced the doctrine of the inerrancy of the Bible at a time that they enslaved millions of Africans for hundreds of years and committed genocide against American Indian Natives. One of the leading advocates of the Igbo genocide, Chief Jeremiah Obafemi Awolowo – a self-professed devout Christian - later claimed that he was a friend of the Igbo despite blocking food supplies to their dying children on the pretext that he did not want the food to go to the Biafran troops. In contrast, the Igbo have no history of invasions, conquests, massacres, genocides or forced conversion against any other group and despite all the atrocities visited against them, they constantly demonstrate their goodwill by returning to the killing fields across Nigeria to provide essential services to their fellow citizens, name their children after other ethnic groups, adopt their styles of dressing and even teach their children other tongues as a first language. Yet the hatred continues perhaps due to envy over the astounding success of the Igbo, according to Achebe who suggests that Nigerians prefer mediocrity to empowering Igbo excellence for the benefit of the whole country.

9) Achebe repeatedly praised the roles of women and indigenous technologies in helping the Igbo to survive the genocidal war. Women conjured up food to feed their families and fed the children folktales as Ngugi also reported in ‘Dreams in a Time of War’; they took great care of dying kwashiorkor babies as if they were beauty pageant contestants; they took refugees into their homes and charged no rents but offered to cook rice as a delicacy for the family of the teacher (Achebe’s father) who was credited with introducing the town to rice as a staple food; they worked as nurses and organized the control of traffic without being asked; but above all, they organized educational classes during the war while also loving their husbands, making more babies; they also hid even eight year old daughters from drunken Nigerian soldiers who repeatedly massacred thousands of the Igbo males they could find in places like Asaba and Calabar but spared the valuable women as war booties. A Goddess was credited with helping to repel the enemy soldiers from the Oguta hometown of one of the heroines, the novelist Flora Nwapa and the Marxist anthropologist, Ikenna Nzimiro. The Biafran Army also devised Ogbunigwe explosives, built armored fighting vehicles, refined petroleum and flew their own planes to the amazement of neighboring African countries that still believed that only white people could fly planes. The diplomats of Biafra continued seeking a peaceful end to the war and drafted the Ahiara Declaration (modeled after Nyerere’s Arusha Declaration) in line with the African virtues of tolerance and accommodation that Nelson Mandela personified when he came out from unjust imprisonment and avoided a race war and an ethnic war, served only one term as president and handed over to a younger generation.

10) Implicitly, Achebe is calling on us to rebuild the African Mbari houses to accommodate all irrespective of race, class, gender or religion. The limitation of his analysis is that it is pitched at the Nigerian national level and not open to the possibilities that Du Bois, Azikiwe, Nkrumah, Nyerere, Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Fela Kuti and Moumar Gadhafi envisaged – a united republic of all Africans that would make it impossible for any group ever again to rise up and attempt to destroy any ethnic group in Africa. The Biafra war involved African countries as supporters on both sides but the solution was wrongly seen by the OAU as an internal affair of Nigeria. Within the People’s Republic of Africa, such a genocidal war will no longer be tolerated in the future as it has been across Africa. The corruption and ineptitude that Achebe blames for the stunting of the development of Nigeria following the marginalization of the enterprising Igbo would be reduced when all Africans have the right to move to any part of Africa and settle, work, study, marry, trade and contest for office as is the case in the US today. Let us turn the 55 countries in Africa into 55 states or more. The African masses have already voted with their feet by disregarding the fictitious colonial boundaries, it is high time we brought policy in line with the lived experiences and realities on the ground and finally synthesize the contradictions between our past and present theses and counter-theses into deeper democratic traditions that are consistent with African cultural virtues of tolerance and accommodation; Udoka (Peace is greater, in Igbo) or Ubuntu (‘the bundle of humanity’, according to Soyinka, citing Desmond Tutu). Soyinka, in Of Africa, agrees that the resolution of the fiction of exclusivity and boundary enforcement should be pursued in the self-interest of Africans rather than in the interest of those who divided and weakened Africa but not only in the direction of dissolution towards micro-nationalism but more importantly in the direction of greater unity across borders, despite the failure of some tentative experiments in that direction in the past.

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org or comment online at Pambazuka News.

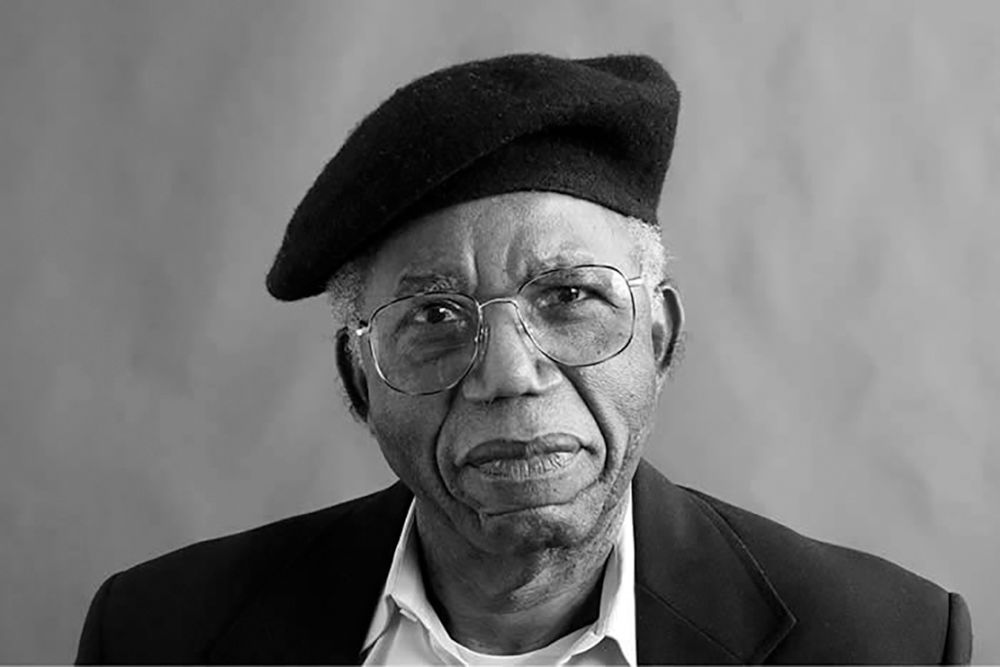

* Biko Agozino is Professor of Sociology and Africana Studies, Virginia Tech.