Mwalimu Apita: Remembering the generation that fought Empire

Nikanori Apita used the classroom to shape the minds of generations, weaning them out of racist ideology of Empire that cramped their mental growth. Empire’s ideology was ingrained in the colonial texts it was his duty to teach. Apita decided his task was to subvert the texts.

Most people agree that the colonial project in Africa was apartheid, extended beyond the borders of South Africa to the rest of the continent. In colonial Kenya they called it the Color Bar. Color Bar restricted Africans to scrubland while whites owned the good land.

French, Portuguese, Belgian, it didn’t matter which colonial power. It was all the same. In Uganda where racism appeared less virulent, whites lived magnificently in immaculate colonial suburbs while Africans lived in the shantytowns.

In her book on the Buganda monarchy, Barbra Kimenye, a friend of Mutesa II of Buganda, describes how local whites shooed away the mighty King when his limousine strayed into a whites-only area of Kampala. The young king took this in stride. Filled with the sense of their own superiority whites believed they had a right to rule in Africa.

Born in 1930 among the Langi of northern Uganda, Nikanori Apita was of a generation that breathed and lived this reality. His generation arrived at a time when European conquest of the continent was complete and all active opposition ended. More than any other, Apita’s generation endured the crudity of colonial contempt. “We are here to rule! You will have to obey. You can do nothing about it.”

Many of these young people went on to acquire college education. Out of their sufferings came great things. Chinua Achebe (born 1930) wrote Things Fall Apart. He wrote this under the dire necessity for one to tell one’s own story, for a people to have their own voice. Today the book is among the first three on most lists of ten greatest novels of the 20th century. Okot p’ Bitek (born 1930) wrote Song of Lawino, long since anthologized in Great Works of the 20th Century. Okot wrote his book out of a feeling that seized him as he attended a lecture at Oxford University where Africa and Africans had become the subject of abuse. Wole Soyinka (born 1934) won the first African Nobel Prize for literature in 1986. Ali Mazrui (born 1933) became one of the most celebrated academics of the 20th Century.

Nikanori Apita was born to parents who were new converts to Christianity. Christianity despite its philosophy of brotherhood and sisterhood, and despite its origins in a largely nonwhite Middle East, became part of the European project in Africa and was deeply involved with apartheid.

In this white-ruled universe came one lone white figure. He was larger than life. Larger than the District Commissioner who was the local embodiment of Empire. The name was Tom Lawrence. A young churchman who arrived in Lango in 1926. Unlike most white men of the day, Lawrence was something more than Empire. In apparent opposition to colonialism, Lawrence believed that change would come to Africa. He put his trust and his hope in education. He walked the talk.

By 1928, two years after his arrival, Lawrence had erected a rock solid church that stands to this day in all its original magnificence. He established a teacher training college to serve the vast area of Uganda then called Northern Province.

Lawrence preached the word and extended education. Under his influence, Boroboro become the center of education in Lango land and beyond. Ever so musical, locals immortalized the place in a song: “The Big School Bell at Boroboro says come, come, come to school”.

One day in 1930, Lawrence heard the good news of the birth of a child and came to see the proud parents who had been students at his adult literacy class. He demanded of them: “You will send this child to school to Boroboro as soon as he is ready”.

And so they did. But it wasn’t soon. The boy arrived to take his place at Boroboro Junior Secondary School in 1949. By then he was already, a young man of 18. But Apita arrived with a load of local lore that stood him well. He made good grades and did extremely well and found his way to the new and prestigious government secondary school that had just opened in Gulu, named for the explorer Samuel Baker. There the young man’s stars continued to rise. In 1954, Apita was again among the first to be admitted to the new and even more prestigious Government Teachers College at Kyambogo near Kampala.

By January of 1957, Apita was back where it all began at Boroboro Hill. This time the young man arrived as a teacher. To teach history and literature, his twin passion. In 1957 despite Ghana and its Kwame Nkrumah, colonialism in Africa was an ongoing project. Many whites believed in the idea of permanent white rule.

In Ghana’s independence, declared May 25 1957, Apita found his mission. He resisted the lure to join politics. He would use the classroom to shape the minds of the coming generation. Wean them out of racist ideology of Empire that cramped their mental growth. Empire ideology was ingrained in the colonial texts it was his duty to teach. His task was to subvert the texts from within. In his literature class Tom Brown of Tom Brown’s School Days, (an attractive literary hero if ever there was one) becomes less and less of a hero. Until the whole class finally see Tom for what he was, a young colonial in training. Apita pulled this off under the nose of watchful colonial officials.

But Apita soon left the classroom to return to college at Makerere University, the better to equip himself to serve the newly independent Uganda, later becoming a District Commissioner. This was the one office that under Empire had underpinned colonial rule. It was a tricky thing following in the footsteps of departed colonials. But Apita played it differently and transformed this otherwise law and order department into something of a community enlightenment and education center.

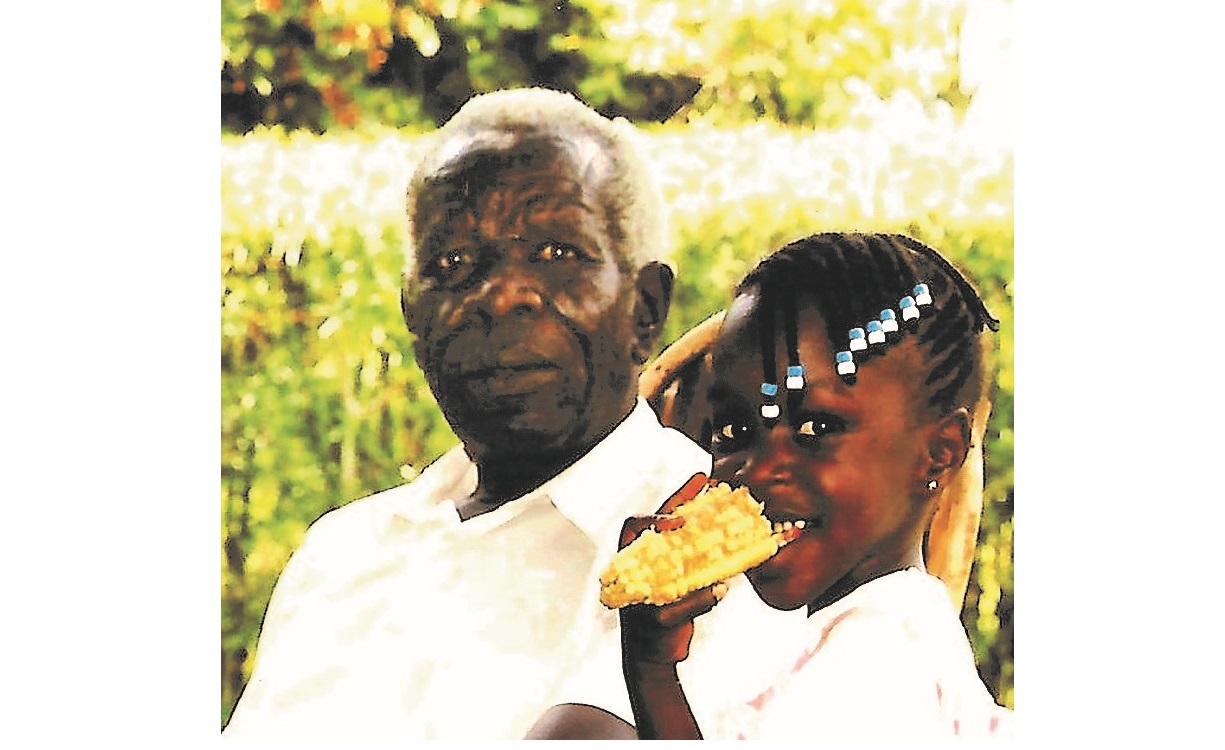

Today in the places he served many carry fond memories of him. Apita died recently at his home in Boroboro where the Big School Bell still says: Come, come, come to school.

*JOHN OTIM is a writer, journalist and poet, and is with All Saints University Lango. [email protected]