Musée Du Quai Branly changes name

An exhibition will be held at the Musée du quai Branly in honour of former French President Jacques Chirac from 21 June to 9 October 2016. This exhibition and renaming of the museum after Chirac do not change the status of the artefacts: They were looted from Africa and other places and the rightful owners want them back.

"African art, like any great art, some would say, in any case more than any man transmitted to objects by man and his society. This is the reason why one cannot separate the problem of the fate of African art from the fate of the African man, that is to say the fate of Africa itself.” -Aimé Césaire, Discours sur l’art africain. [1]

Several media have reported that the Musée du quai Branly, Paris, which experienced some difficulties at birth about receiving an appropriate name, and finally settled simply with the name Musée du quai Branly, after the quay where it is located, will change or modify its name to Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac when the former French President Jacques Chirac passes away.[2]

According to the the issue of Le Monde of 21 June 2006, (a day after the museum was opened), Jacques Chirac had expressed the wish not to have any grand work named after him, as was the French tradition when a president died. His predecessors have Centre Pompidou and the Bibliothèque National François Mitterrand named after them. Chirac did not want his name to be inscribed in concrete for posterity. It seems this wish will not be respected and like his predecessors, he would have a most controversial museum named after him when he passes away. As Le Monde explained, the Musée du quai Branly owes its existence to the efforts of Jacques Chirac who had been convinced of the need for such a museum by his friend, Jacques Kerchache, a dealer in non-Western Art, whom he met during holidays at a beach on the island of Mauritius. [3]

This modification or amplification of name will come as no surprise to those who have some idea about the origins of the museum. [4] Sally Price seems to have anticipated this change of name some years ago when she entitled her excellent book, Paris Primitive: Jacques Chirac’s Museum on the Quai Branly [5].

We have always maintained the position that where the West places looted or stolen African artefacts or whom the West praises for contribution to the looted lot, is in principle, not our primary concern. Whether the French place looted African artefacts in Musée de l’Homme or build a new museum for the artefacts, as in the case of the Musée du quai Branly, the status of the artefacts remains the same: illegal and illegitimate. [6]

Notwithstanding this self-imposed limitation, we reserve the right to comment on any matter that might mislead the reader or create a false impression and might contribute to a wrong appreciation of exact relations between Africa and the West. Besides, we are interested in knowing where our artefacts are and who is keeping them. Many African peoples are not exactly aware of where their looted artefacts are in the West where they cannot obtain a visa for visit. It is interesting to note that many members of the Benin delegation to the Benin exhibition Benin-Kings and Rituals; Court Arts from Nigeria in 2007, in Vienna, were seeing many of the artefacts for the first time since they were stolen by the British in the notorious Punitive Expedition of 1897 and sold to German and other Western museums. The British Museum was not among the organizing museums of the 2007 Benin exhibition, although it did lend some objects but not the iconic hip-mask of Queen-Mother Idia.

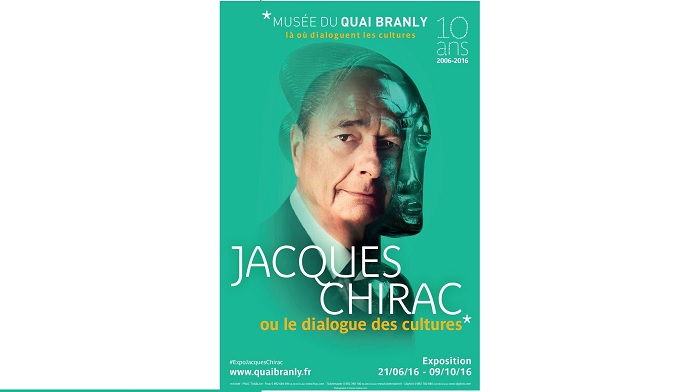

An exhibition will be held at the Musée du quai Branly in honour of Jacques Chirac from 21 June to 9 October 2016, Jacques Chirac ou le dialogue des cultures, showing 200 selected artefacts that have a link to the former President. The poster shown above has been issued in connection with the coming exhibition. We do not have any official or other interpretation of the image of Jacques Chirac that almost merges into an African mask. Does this imply that Chirac in his activities acted like an African or became an African? Or that the French President acted in the interest of Africa? In any case, the unusual merging of the image of a former French President with a mask from a foreign culture, for that matter an African culture, needs to be fully explained. We hear already people talking about ‘Chirac, l’Africain’ and thus starting a myth about the relationship of the former President with Africa, putting him perhaps in a more favourable light.

Before anyone gives the misleading impression that in his inaugural speech at the opening of the Musée du quai Branly, the French President fought for Africans and African art, we should be reminded of what the former Malian Minister of Culture, the great Aminata Traoré, correctly stated about the fundamental contradiction lying at the basis of the establishment of the new museum: our artefacts have a right of residence in a place where we ourselves are not allowed to enter and we are requested to celebrate with the former colonial power and witness our own defeat, decline and impotence. [7]

In his statement at the opening of the Musée du quai Branly, Jacques Chirac blamed the miserable state of the African peoples and others, not on Western slavery, colonialism and imperialism but on History.

“France wished to pay a rightful homage to peoples to whom, throughout the ages, history has all too often done violence. Peoples injured and exterminated by the greed and brutality of conquerors. Peoples humiliated and scorned, denied even their own history. Peoples still now often marginalized, weakened, endangered by the inexorable advance of modernity. Peoples who nevertheless want their dignity restored and acknowledged’. [8]

‘History’, in the abstract, is blamed for the parlous state of the African and Asian states. Even at this stage, Westerners are not willing to admit that the Western colonial system was a criminal and devastating enterprise that left many countries and peoples in abject conditions. Slavery and colonialism which enriched the Western world are passed over quietly and certainly not directly mentioned. The pseudo-humanist tone of the French President did not deceive anyone and certainly no African or Asian conversant with the colonial enterprise would be deceived by such statements.

The massacres and exterminations of African peoples, the enslavement of our brothers and sisters, the humiliation and denigration ensuing, and the exploitation of our natural resources were not organized by ‘History.’ The British, Belgians, French, Germans and Portuguese were the organizers of unspeakable sufferings on the African Continent. And this must be said without fear or hatred for the benefit of all. [9]

The homage by the Musée du Quai Branly to Jacques Chirac is designated, ‘Jacques Chirac ou le dialogue des cultures’. As we have insisted in our writings, there cannot be any genuine dialogue so long as the past relations of slavery and colonialism are not honestly approached on both sides. A background of unexamined resentments and unexplored suspicions, compounded by the traditional Western arrogance and assumptions of congenital superiority, even when the West is holding our looted objects, clearly cannot be conducive to genuine understanding even if some Western individuals declare themselves free from such complexes. We need a general change of attitude by a sizeable part of the society concerned. This has so far not been demonstrated in any Western State even though remarkable individual persons may have made the transformation.

We are not concerned with assessing whether Jacques Chirac deserves the honour of having a museum named after him that holds looted African and Asian artefacts but contains no French or European artefacts; a museum that was tainted with illegality even before its birth not only by the two museums that would provide it with looted objects but also by the illegal acquisition of looted Nok pieces for the Palais des Sessions where objects for the future museum were kept. This is a matter for the French people. The opinion of Africans and Asians whose artefacts are in the museum has not been requested.

It is an incredible paradox of our times that, contrary to all laws, morals and religions, Western museums seem capable of generating honour or an aura of honour from contested assemblages of looted/stolen artefacts of others despite vehement protests from the angry dispossessed owners who regard their spoliation as daylight armed robbery. Western armies staged such daylight robberies in Beijing, China 1860, Maqdala, Ethiopia, 1868, Kumasi, Ghana, 1874, and in Benin, Nigeria, 1897.

The Chinese, Ethiopians, Ghanaians and Nigerians have never forgotten such defeats and humiliations. They probably can never forget such humiliations so long as those looted objects are displayed by Western museums as trophies of conquerors and signs of superiority. It is also in the nature of so-called ethnological objects that they ‘shout’ their origins. Even the youngest visitor to the museum would ask, ‘Where did it come from and how did it reach here from Africa?

We will also avoid discussing the merits of the Chirac Government for another basic reason: to avoid what we call displacing the issue or argument. Supporters of holders of illegal and illegitimate artefacts of others are very good at displacing issues. Instead of concentrating on the issue of legitimacy and legality, irrelevant arguments are brought in about how efficient the present illegitimate holders are, as opposed to the rightful owners. We are also informed about how secure Western museums are as opposed to African museums, even though there have been spectacular robberies in Western museums. We hear also Western climates are better for preserving African artefacts even though these artefacts were made in Africa and stayed there for centuries before the Europeans stole them. We hear often that the West has air-conditioners and similar modern devices.

What is clear is that many Westerners do not wish to admit that these looted and stolen artefacts ought to be returned or some arrangements be made with the rightful owners in Africa and Asia. This should have been done as part of the Independence process if the West really sought to create better relations with the new states, free of fear and resentments.

Westerners who have several anniversaries and commemorations in a year often tell us Africans to forget the past whenever slavery, colonialism and looted artefacts are mentioned. They do not seem to realize that this advice would put us exactly where we were supposed to be at the beginning of Western colonization: peoples without history. Nobody ever advises the Greeks, the Italians, the British or the French to forget their histories. The general insensitivity of our contemporary Westerners is what discourages many Africans from discussing with them. One gets the impression that most of them have not heard about the colonial period or do not understand what colonial rule meant for Africans.

French or other Western celebrations of their presidents or other leaders cannot be viewed by Africans outside the general framework of our relations with the West if we are not to falsify our own history.

But what are African states and their cultural officials saying? Are they using every opportunity to request the return of the looted artefacts or are they keeping silent, as if they were not concerned? What is Nigeria, with its claim to leadership in this as in other areas, saying? We have read information praising France and presenting France as model for restitution of cultural aretefacts but there is not a word about the three looted Nok pieces in the Palais des Sessions, held by the Musée du quai Branly.

Are Nigerian officials more concerned by other matters in Paris than by national treasures that are illegally held there, undoubtedly with a post factum consent of the government? This is of doubtful legality, insofar as a government cannot retroactively accord legality to the illegal purchase of looted artefacts prohibited by law from exportation outside the country. Governments are also subject to the internal laws of their countries. [10]

Given the prevailing neo-colonial relationships and the widespread pragmatism, some African states and museums may already have sent congratulatory messages in order to initiate their invitation to the opening of the forthcoming exhibition in honour of Chirac. Hopefully they are not preparing to celebrate this change of name. If they do celebrate, they must ask themselves what they are celebrating.

Frequent demonstration of lack of self-respect and the absence of adherence to principles and consistent policies are clearly not likely to contribute to the restitution of any of the thousands of African cultural artefacts that are in Westerns museums and homes.

“Cultural heritage constitutes an inalienable part of a people’s sense of self and of community, functioning as a link between the past, the present and the future; It is essential to sensitize the public about this issue and especially the younger generation. An information campaign may prove very effective toward that end; Certain categories of cultural property are irrevocably identified by reference to the cultural context in which they were created (unique and exceptional artworks and monuments, ritual objects, national symbols, ancestral remains, dismembered pieces of outstanding works of art). It is their original context that gives them their authenticity and unique value.” [11]

* Kwame Opoku is an independent scholar and commentator about African cultural affairs.

NOTES

1. « L’art africain comme tout grand art, me dira-t-on, en tout cas plus que tout autre, et depuis si longtemps si ce n’est depuis toujours, est d’abord dans l’homme, dans l’émotion de l’homme transmise aux choses par l’homme et sa société.

C’est la raison pour laquelle on ne peut séparer le problème du sort de l’art africain du problème du sort de l’homme africain, c’est-à-dire en définitive du sort de l’Afrique elle-même »Aimé Césaire, « Discours sur l’art africain »

in Annick Thebia-Melsan, Aimé Césaire : Pour regarder le siècle en face, (2000, Maisonneuve & Larose, p. 25). The above extract has been taken from a brilliant statement Aimé Césaire wrote , in response to André Malraux who had given a statement on African art at the opening of the “Colloque sur l’art dans la vie du people,” Dakar, 30 March-7 April 1966. (Translations from the French are by K. Opoku.) Even André Malraux, a man of culture, could not avoid declaring that African peoples must forget their past. Malraux had declared that what the African masks represented, like what the European cathedrals represented, was lost for ever. Africans must take into account the changes in African art and society. They must build the future on the basis of a present which did not have the same relationship with the past as it was previously. The magic world that the masks created could no longer be found again. Césaire however argued that African art depended on the African who depended on a future Africa which had not been cut off from its traditions. See Aimé Césaire, Études litteraires, vol 6, no.1, 1973, pp. 99-109. http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/500270ar Malraux’s idea suggests an African art developing with no connections to the much admired sculptures whereas Césaire correctly points out that African art is a reflection of African society and one cannot separate the one from the other. African traditions are still with us.

Perhaps Malraux, a French intellectual and a Minister of Culture under General Charles de Gaulle, aware of the importance of African art, especially African sculpture, for modern art, could probably not imagine a situation where African sculptures would be removed from French museums and leave French artists without the inspiration that undoubtedly comes from the massive presence of African art objects in France. His ideas and theories had to ensure the continued presence in France of the looted/stolen artefacts from Africa and Asia that fill French museums and homes. The universalist theory he supported was on the assumption that Europeans would annex or detach African artefacts from their social and historic context whereby the objects lose their functions in their society and become art in the ‘imaginary museum’. We are certainly not confusing the ‘universal museum’ of James Cuno and Neil MacGregor with the ‘musée imaginaire’ of Malraux. The effect of both conceptions is to leave the looted African artefacts in Western museums. For a useful explanation of Malraux’s ‘muséee imaginaire’, see Derek Allen, ‘André Malraux, The art of the museum, and the digital musée imaginaire’

http://www.home.netspeed.com.au/derek.allan/musee%20imaginaire.htm

See also, Jean-Pierre Zarader, André Malraux-Les écrits sur l’art, Editions Cerf, Paris, 2013.

The theme of Andre Malraux and Africa can be pursued further with the

publication by Présence Africaine, Malraux et l’Afrique, Actes du colloque international, 2012.

2. New name for the Musée du quai Branly in Paris?

theartnewspaper.com/.../new-name-for-the-mus-e-du-quai-branly-in-paris

http://myinforms.com/en-us/a/30557918-new-name-for-the-muse-du-quai-branly-in-paris/

Musée du Quai Branly to be renamed Musée Chirac | Bruno ...

brunoclaessens.com/2016/04/musee-du-quai-branly-to-be-renamed...

New name for the Musée du quai Branly in Paris? - Arts ...

www.newslocker.com/.../new-name-for-the-muse-du-quai-branly-in-paris

http://www.france24.com/fr/20160414-le-musee-quai-branly-portera-bientot-le-nom-jacques-chirac

www.france24.com/fr/20160414-le-musee-quai-branly...nom-jacques-chirac

Le Musée du Quai Branly portera aussi bientôt le nom de Jacques Chirac www.boursorama.com › Actualités › Générales › France

Le musée du Quai Branly bientôt renommé Jacques Chirac selon "Le ...

www.huffingtonpost.fr/.../musee-quai-branly-jacque.

3. Jacques Kerchache (1942-2001) spent six months in jail in Gabon for illegal

export of artefacts. In many Western circles offences relating to artefacts of

non-European peoples are regarded as mere adventurousness, a mark of youthful

exuberance and presented as badges of honour or bravery. Kerchache, a

multitalented personality, was equally hated and admired. President Chirac

wrote in an homage to Kerchache: ‘Jacques Kerchache était mon ami’. (Jacques

Kerchache was my friend) in Jacques Kerchache, Portraits Croisés,

(Gallimard/musée du quai Branly, 2003) The book contains many positive

assessments by his friends and those who knew him well. See also the

catalogue, Jacques Kerchache-Itinéraire d’un chercheur d’art, 2003 in which

President Chirac states that it was on the advice of Kerchache that he decided to

create the Musée du quai Branly and praises the genius of Kerchache :

On the other hand, we have some very damaging critical assessment of Kerchache by Bernard Dupaigne, former head of Musée de l’Homme, in his book, Le scandale des arts premiers- La veritable histoire du muse du quai Branly, (Edition Mille et une nuits, Paris, 2006).Sally Price has an interesting and useful chapter on Jacques Chirac and Jacques Kerchache, entitled ‘Jacques and Jacques’ in Paris Primitive, Jacques Chirac’s Museum on the Quai Branly, University of Chicago Press, 2007, pp.1-18.Benoît de L’Estoile has some pertinent remarks on Kerchache in Le goût des autres-De l‘exposition coloniale aux arts premiers, Flammarion, 2007, pp. 261-287.Jacques Kerchache published books on African art, including, L’Art africain, Citadelle et Mazenod,1988.

4. K. Opoku, ’ What are they really celebrating at the Musée du quai Branly, Paris?’

5. University of Chicago Press, 2007. See a review of this book, ‘The Logic of Non-Restitution of Cultural Objects’ www.museum-security.org/2007/11/the-logic-of-non-restitution-of... The French version of Sally Price’s book leaves out the name of Jacques Chirac in its title, Au musée des illusions: le rendez-vous manqué du quai Branly. Denöel, Paris, 2011. It would be interesting to see whether the second edition of the French version will somehow restore the name of Chirac on the cover.

6. K. Opoku,’ Musée du quai Branly, a museum for the art objects of others or for the looted art objects of others?

K. Opoku, ‘Briton of the Year: Neil MacGregor’, www.elginism.com/british-museum/british-museum-director-is-briton...

7.Aminata Traore, « Ainsi nos œuvres d'art ont droit de cité là où nous sommes, dans l'ensemble, interdits de séjour » https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aminata_Traoré

8. Allocution de M. Jacques Chirac, Président de la République

à l’occasion de l’inauguration du musée du quai Branly.

(Paris, 20 juin 2006) https://pastel.diplomatie.gouv.fr/editorial See Annex I. for the English text.

9. Caroline Elkins gives us a gruesome picture of British imperialism in Kenya in her book, Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya 2005,Henry Holt and Co. Cecil Rhodes & De Beers: Genocide Diamonds | The Espresso ...

Adam Hochschild has dealt with the cruelties of the Belgians in King Leopoldt’s Ghost: A Story of Greed,Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa,2012, Pan,Main Market Edition.

The literature on Germany’s cruel rule in Africa is extensive. David Olusoga and Casper W.Erichsen,The Kaiser’s Holocaust Germany’s Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism, Faber and Faber, 2010; see also K.Opoku, ‘Have Germans Finally Acknowledged Their Extermination Wars Against The Herero, Nama, San And Damara As Genocide?

https://www.modernghana.com/.../have-germans-finally-acknowl..

The classic on colonial misrule is Andre Gide,Voyage au Congo, Gallimard,1955. Another classic on the cruel nature of French colonial domination is Terre d’Ebénè by Albert Londres, Arlea, Paris,1922. We have also the legendary text from Aimé Césaire, Discours sur le colonialism,Présence Africaine,1955. A good English translation is by Joan Pinkham, Discourse on Colonialism, Monthly Review Press,New York,2000.

A report commissioned by the French Government contained such damaging matters that it was decided not to publish it: Le rapport Brazza. Mission d’enquete du Congo: rapport et documents (1905-1907) published in 2014 by

Le Passager Clandestin,with a preface by famous French historian,Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch,

10. Folarin Shyllon, “Negotiations for the Return of Nok Sculptures from France to Nigeria – An Unrighteous Conclusion,”

Art, Antiquity and Law8 (2003): 133-148 .See also. http://portal.unesco.org

See Sally Price’s account of the illegal acquisition of the Nok pieces in Paris Primitive, pp.67-80; K. Opoku, Revisiting Looted Nigerian Nok Terracotta Sculptures in Louvre/ Musée du quai Branly, Paris,

11. Conclusions of the Athens International Conference on the Return of Cultural Objects to their Countries of Origin Athens, 17-18 March 2008. http://portal.unnesco.org

ANNEX

OPENING OF THE MUSEE DU QUAI BRANLY SPEECH BY PRESIDENT JACQUES CHIRAC

12 November 2007. English text from Australian Government, Australian Council for the Arts australiacouncil.gov.au/.../speeches/opening-of-the-...

Address by M. Jacques Chirac, President of the French Republic, at the opening of the Musee du Quai Branly, Paris, and Tuesday 20 June 2006.

Kofi Annan, Secretary-General of the United Nations, Abdou Diouf, Secretary-General of the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie, Prime Ministers, Ministers, Ladies and Gentlemen, Friends.

It is an immense joy and thrill for me to be here with you, who have come from all over the world, to open the Musee du Quai Branly today. Thank you kindly for accepting my invitation to this opening, which, I think, is an event of great cultural, political and moral significance.

A visit to this new institution dedicated to other cultures will be at once a breathtaking aesthetic experience and a vital lesson in humanity for our times.

As the world's nations mix as never before in history, the need for an original venue was felt, a venue that would do justice to the infinite diversity of cultures and offer a different view of the genius of the peoples and civilisations of Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas.

Moved by that sense of respect and acknowledgement, in 1998 I decided to create this museum, in agreement with the prime minister, Lionel Jospin.

France wished to pay homage to peoples to whom, throughout the ages, history has all too often done violence. Peoples injured and exterminated by the greed and brutality of conquerors. Peoples humiliated and scorned, denied even their own history. Peoples still now often marginalised, weakened, endangered by the inexorable advance of modernity. Peoples who want their dignity restored.

This is the spirit behind the declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples that we are drafting in Geneva and on which I know the Secretary General of the United Nations, Mr Kofi Annan, and my friend Rigoberta Menchu Tum place great importance.

This is the spirit, Eliane Toldeo, in which I hailed the election of your husband as president of Peru. This is the reason that inspired me, Paul Okalik, Premier, to travel to Nunavut, with our mutual friend, Jean Chretin, in 1999.

Central to our idea is the rejection of ethnocentrism and of the indefensible pretension of the West that it alone bears the destiny of humanity, and the rejection of false evolutionism, which purports that some peoples remain immutably at an earlier stage of human evolution, and that their cultures, termed "primitive", only have value as objects of study for anthropologists or, at best, as sources of inspiration for Western artists.

Those are absurd and shocking prejudices, which must be combated. There is no hierarchy of the arts any more than there is a hierarchy of peoples. First and foremost, the Musee du Quai Branly is founded on the belief in the equal dignity of the world’s cultures.

I would like to pay homage today to the men and women who inspired the museum, starting with the late Jacques Kerchache.

With him, in 1992, while in different parts of the globe the quincentenary of the discovery of America was being celebrated, we decided to organise a major exhibition in Paris dedicated to the civilisations of the Greater Antilles, and in particular to the Tano Indians of the Arawak group, the people who welcomed Christopher Columbus to the shores of the Americas but were subsequently exterminated. It is also to Jacques Kerchache that we owe the admirable rooms of the Pavillon des Sessions at the Louvre.

I also extend my warmest thanks to all the men and women who helped bring the Musee du Quai Branly into existence and who surpassed themselves to ensure that everything was complete on time.

Jean Nouvel, Gilles Clement, and their teams, who have crafted a building of masterful architecture, suffused with respect for the visitor, the environment, the works and the cultures that produced them.

Germain Viatte and the curators, whose superb museography interweaves approaches and dissolves the artificial distinction between art and anthropology, affording visitors the pleasure of discovery and sensitivity and inviting them to open their eyes and broaden their horizons.

Stephane Martin and his staff, who administer this original institution and will assuredly make it an uncontested centre for education, research and dialogue and a venue for contemporary art, testifying to the vitality of the cultures to which it is dedicated. A vitality to which the magnificient Australian Aboriginal ceilings testify.

I also express my profound gratitude to all the patrons who have rallied round the project and supported it so generously.

The Musee du Quai Branly will, of course, be one of the largest museums dedicated to the arts and civilisations of Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas, with a collection of almost 300,000 pieces, including exceptional works, such as this totem pole from British Columbia and the splendid monumental Djennenke sculpture from the Bandiagara Plateau in Mali.

But it is much more than a museum. By multiplying viewpoints, the venue’s ambition is to render the depth and complexity of the arts and civilisations of all those continents. In so doing, it seeks to encourage a different - more open and respectful - view in the broadest possible audience, by dispelling the mists of ignorance, condescension and arrogance that, in the past, so often bred mistrust, scorn and rejection.

Far removed from the stereotypes of the savage or primitive, the museum seeks to communicate the eminent value of these different cultures - some of which have been lost, many of which are endangered - these "fragile flowers of difference" in the words of Claude Levi-Strauss, which must be protected at all costs.

Because "the first peoples" possess a wealth of knowledge, culture and history. They are the custodians of ancestral wisdom, of refined imagination, filled with wonderful myths, and of high artistic expression whose masterpieces rival the finest examples of Western art.

By showing that there are other ways of acting and thinking, other connections between beings, other ways of relating to the world, the Musee du Quai Branly celebrates the luxuriant, fascinating and magnificent variety of human creativity. It proclaims that no one people, no one nation, no one civilisation represents or sums up human genius. Each culture enriches humanity with its share of beauty and truth, and it is only through their continuously renewed expression that we can perceive the universal that brings us together.

That diversity is a treasure that we must preserve now more than ever. In globalisation, humanity is glimpsing the possibility of unity, that age-old dream of the Utopians, which has become the promise of our destiny. At the same time, however, standardisation is gaining ground, with the worldwide expansion of the law of the market.

But who can fail to understand that when globalisation brings uniformisation it can only exacerbate tensions between different identities, at the risk of igniting murderous violence? Who does not feel a new ethical imperative, faced with the confusing questions thrown up by the rapid development of scientific knowledge and our technological achievements? As we search falteringly for a development model that would conserve our environment, who does not seek another way of looking at man and nature?

That is also the idea behind this museum. To hold up the infinite diversity of peoples and arts against the bland, looming grip of uniformity. To offer imagination, inspiration and dreaming against the temptation of disenchantment. To show the interactions and collaboration between cultures, described by Claude Levi-Strauss, which never cease to intertwine the threads of the human adventure. To promote the importance of breaking down barriers, of openness and mutual understanding against the clash of identities and the mentality of closure and segregation. To gather all people who, throughout the world, strive to promote dialogue between cultures and civilisations.

France has made that ambition its own. France expresses it tirelessly in international forums and takes it to the heart of the world's major debates. France bears it with passion and conviction, because it accords with our calling as a nation that has long prized the universal but that, over the course of a tumultuous history, has learned the value of otherness.

Ladies and Gentlemen, more than ever, the destiny of the world lies in the capacity of peoples to have an enlightened view of each other and share their differences and cultures, so that, in its infinite diversity, humanity can gather around the values that unite it.

May the visitors who pass through the doors of the Musee du Quai Branly be filled with emotion and wonderment. May they come to realise that this knowledge is irreplaceable. May they in turn become bearers of the message of peace, tolerance and respect for others.

Thank you.