A Pan-African agenda for the 21st century

The overall objective of the conference was to establish modes of deepening African unity and to identify concrete practical steps for charting the way forward for pan-Africanism in the twenty-first century in the face of renewed imperialist aggression.

On Monday 26 June 2017, a most important event for the future of the Global African family took place on African soil at the University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana. It was a gathering of Africans and pan-Africanists, academics, activists, political leaders, students and youth from all over the world at the opening ceremony of the 2nd Kwame Nkrumah Pan-African Intellectual and Cultural Festival.

In a day characterised by seriousness of purpose, commonality of ideas and sense of mission, the foundation of the meeting was set by Kwame Nkrumah Chair of African Studies Professor Horace Campbell who, in welcoming the participants, provided what can only be described as a masterful “update” of the state of the black condition globally. Prof Campbell achieved the simultaneous goal of updating participants on the specific struggles in specific regions but also demonstrated to all and sundry how their struggles are interlinked.

In what was described, by Joseph Engwenyu, a historian from Uganda, as the most powerful opening ceremony to any global conference that he has ever attended, nowhere was left untouched and analysed in Campbell’s welcome: from the struggles against neo-liberalism in Latin America and the deliberate overthrow of the ordered states of Libya, Iraq and Syria and North Africa and the Middle East, significantly worsening the lives of black citizens in these countries, but more importantly, reversing the possibilities of the economic and material advancement of the pan-African project which was being led by Libya.

In his roll call, Campbell noted the physical absence of Haiti, but was moved to invoke their presence in spirit, since he affirmed that it is impossible to hold a gathering of this nature without acknowledging Haiti, for its sacrifices in igniting the flame of African liberation globally.

Significantly, too, Campbell highlighted the fact of the re-articulation of renewed imperialist aggression by the United States against people of colour, both within and outside its borders. Arising out of this assessment, Campbell emphasised that the ultimate aim of the conference was to establish modes of deepening African unity and to identify concrete practical steps for charting the way forward as an agenda for pan-Africanism in the twenty-first century.

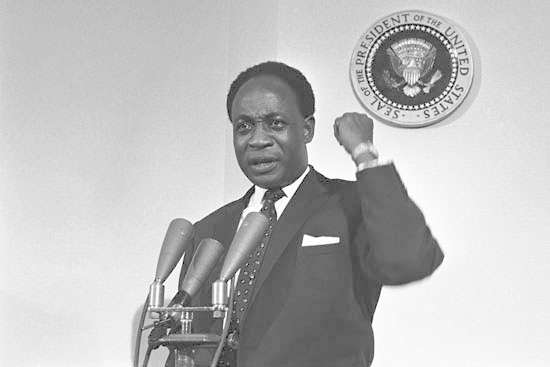

This theme of the need for unity was sustained and reinforced by strong solidarity messages, the most symbolic being delivered by Samia Nkrumah, the daughter of Ghana’s founding president and eminent pan-Africanist Kwame Nkrumah, who insisted on the need to re-affirm Nkrumah’s message of continental unity: one economy, one currency, one army, one foreign policy and one government. Given the convening of a conference called under the name of Kwame Nkrumah, it was a significant wake-up call, which placed the ultimate vision of Nkrumah squarely at the centre of the consciousness of the participants.

The opening ceremony was presided over by the Vice Chancellor of the University of Ghana Professor Ebenezer Owusu. After the welcome statement by the Director of the Institute of African Studies Professor Dzodzi Tsikata, there were solidarity messages from Barbados, the former Prime Minister of Namibia, Nahas Nangula, representative of the Polisario liberation forces of Western Sahara, Mr M. M. Buyema and Samia Nkrumah, the daughter of Kwame Nkrumah. The President of Ghana was represented by Professor Kwesi Yankah, Deputy Minister of Education.

The highlight of the gathering of this opening ceremony of more than 400 persons in the Great Hall of the University of Ghana was the feature address, delivered by the Vice Chancellor of the University of the West Indies, Sir Hilary Beckles, whose contribution set the analytical and a programmatic guideline for the way forward for pan-Africanism to the mid-twenty-first century.

On reflecting upon the African condition in the context of the Western world’s claim to fighting a war on terror, Prof Beckles noted that no part of the world has had a more brutal experience of terrorism than the Caribbean under European slavery. Having established this fact, Beckles therefore set the stage for reflecting on a future pan-African project.

His proposed program was framed within a recounting of the stance taken by the major African states at the UN Durban World Conference Against Racism in which, according to his recounting, the formal leaders of Africa abandoned the Caribbean delegations in their call for reparations. The powerful symbol left by Beckles was that of a mother (Africa) abandoning her scattered children (the Caribbean). He insisted that something had been broken and needed to be repaired.

Beckles framed his argument on the basis that the Caribbean had “done its part” for Africa, from its intellectual, moral and organisational contribution to the struggles against colonialism and independence through the work of pan-Africanists like George Padmore, to the struggle against apartheid as seen in the work of reggae artistes like Bob Marley, to the military contribution of Cuba in Southern Africa. According to Beckles’s narrative, the children had never walked away from the mother, and that Africa, by turning her back on her children in their hour of need, had inflicted a deep wound in the relationship that needed to be healed. Beckles therefore suggested that before any further forward movement could occur, the African mother would have to reach out to her children in global Africa, as part of the process of healing.

Symbolism aside, this call for the African mother to reach out to her children set the scene for the offering of practical and programmatic agenda which would emerge in the conference. This not only included the role of Africa in supporting the call to spearhead a reparations movement, but it forced upon the conference the need to think about the kind of agenda around which a program of reaching out between Africa and the Caribbean could be built. This represents the first framework for a future pan-African agenda.

The second inference by Beckles, which created a framework for a future program of action for pan-Africanism, was his own recognition of a split between African states and African civil society, which was symbolised in Durban with the support for reparations from African civil society but a rejection of the call for reparations by the states. This recognition of the split over reparations was seen as symptomatic of a deeper crisis of the post-colonial independent state, in which elites have been cut off from the aspirations of the people.

This set the tone for a second major agenda issue of the conference: the need to re-examine the failures of an elite-led independence project and, relatedly, the failures of an elite-led pan-African project. Indeed, this has, at the time of writing, constituted a major aspect of the theoretical and practical aspects of the conference, with many of the papers focussing on re-examining the ideas of Walter Rodney, CLR James, George Padmore, WEB Dubois, Amilcar Cabral, Frantz Fanon, Kwame Nkrumah and others.

In addition, the question of overcoming many of the specific aspects of the failure and reversal of the independence and Pan-Africanism have been placed on the agenda. Thus, issues of education, land reform, an African currency, economic sovereignty, integration, indeed, a re-examining of every major aspect of the ongoing failures of post-colonial experience, was inspired by the recognition of the split between civil society and states.

Finally, above all else, the conference theme was “Global Africa 2063: Education for Reconstruction and Transformation”. The conference, and opening ceremony, created an excellent platform for future links between education institutions between Africa, the Caribbean, Latin America, and North America, and the rethinking of the substance of education into a future pan-African project, towards meeting the African Union’s goal of a unified Africa by the year 2063.

Given the energy of the conference, the crisis of global capitalism, the sense of mission, and the feeling of the urgency of moment, Professor Campbell was moved to warn that African unity will come before 2063. We await the formal release of the Accra Declaration of Action, as a way forward towards pan-Africanism into the twenty-first Century.

* TENNYSON S.D. JOSEPH teaches in the Department of Government, Sociology & Social Work at the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill. He is a prolific writer who pens a weekly column in the Nation. He is the author of Decolonization in St. Lucia: Politics and Global Neoliberalism, 1945–2010, University Press of Mississippi, 2011.

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to [email=[email protected]]editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org[/email] or comment online at Pambazuka News.