Loan of looted Ethiopian treasures to Ethiopia: Must Europeans always win?

The article tells us how on-going debates about stolen African artefacts, in particular those from Ethiopia, and held in Western museums, have divided opinions of policy-makers in Europe.

Loan of looted Ethiopian treasures to Ethiopia: Must Europeans always win?

From this scene I strolled away to the northern gate, to where the dead body of the late

Master of Magdala lay, on his canvas stretcher. I found a mob of officers and men, rudely jostling each other in the endeavour to get possession of a small piece of Theodore’s blood-stained shirt.

No guard was placed over the body until it was naked, nor was the slightest respect shown it. Extended on its hammock, it lay subjected to the taunts and jests of the brutal-minded. An officer, seeing it in this condition, informed Sir Robert Napier of the fact, who at once gave orders that it should be dressed and prepared for interment on the morrow.—Henry M. Stanley [1]

Crown of Tewodros, Ethiopia, now in Victoria and Albert Museum, London

For the last few months, I have been under the impression that Western museum directors have finally understood and accepted that Africans are endowed with the same basic human characteristics as Europeans and all others. That is, intelligence, pride and sensibility. But when I turn to questions of looted art and restitution, I have the impression that some museum directors do not consider us and our peoples as intelligent human beings.

How else should one consider the recent statements by Tristram Hunt, Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum in connection with the exhibition “Magdala 1868”, from 5 April 2018 to 30 June 2019, organized to coincide with the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Magdala? [2] Why is the museum showing only twenty of the thousands of objects looted by the British Army at Magdala?

Gold chalice from Ethiopia looted by British soldiers at Magdala now at Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom.

The history of the British invasion of Ethiopia has been told several times and we shall spare the reader all the terrible details. [3] Simply put, in 1868 a British expeditionary force set out to secure the release of the British Consul and some foreigners held by the Emperor. The Emperor released them, but the British general Napier refused to accept this gesture and continued with their campaign.

The British Army attacked Ethiopia and defeated the Ethiopian forces at the Battle of Magdala on 13 April 1868 resulting in Emperor Tewodros committing suicide with a gun sent them as a gift by Queen Victoria rather than surrender to the invading army. The British Army looted whatever treasures they could find. The British soldiers took more than 500 ancient parchment manuscripts, two gold crowns, crosses and chalices in gold, silver and copper, religious icons, royal and ecclesiastic vestments as well as shields and arms. It took 15 elephants and 200 mules to transport the loot.

It is interesting to note that the context of British attacks and invasions of non-Europeans has often followed similar pattern whether we look at the attack on Beijing (China) in 1860, Magdala (Ethiopia) in 1868, Kumasi (Ghana) in 1874 or Benin (Nigeria) in 1897. [4] The scheme is usually as follows:

Ethiopian cross, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom.

- Existence of lucrative trade in a non-European country or its strategic importance in the region.

- The British seek to take control over trade in the area and meet resistance.

- The British send a team or delegation allegedly to negotiate peace, a delegation that is often secretly armed.

- Some members of the delegation are attacked and killed. In some cases, the alleged killing or imprisonment of some Europeans, such as missionaries, suffices as justification. Even if the prisoners are released or the menaced party offers truce, the invading army presses on.

- Britain sends an army, a punitive expedition army to the non-European country.

- The non-European country is attacked, the government or monarch is deposed and the city or main palace there is burnt. Before doing that, all treasures, including artworks, are looted.

What cannot be taken is burnt. British looting is usually systematic and done with expert advice from specialists who are officially appointed as part of the expedition. This was the situation in most punitive expeditions. For example, Richard Rivington Holmes, an assistant in the manuscripts department of The British Museum, accompanied the expedition against Magdala, Ethiopia, as an archaeologist. They acquired several objects for the British Museum, including about 300 manuscripts, which are now housed in the British Library. [5]

In view of the historical record and the evidence of an established British tradition, it is remarkable that some have tried to argue that the burning of a town such as Benin City was due to an accidental fire started by a soldier or give the impression that looting was done by locals or a few undisciplined soldiers.

The pattern of behaviour of Britain towards states on other continents should be borne in mind when considering present claims for restitution of objects resulting from aggressive colonialist actions. A pattern of this kind, which is traditional in the British Army, cannot be obscured by allegations of instances or incidents. The Ethiopian artefacts are now distributed in universities and institutions such as the British Museum in London, the Royal Library at Windsor Castle, the Bodleian Library in Oxford and Manchester's John Rylands library. Large collections of Ethiopian manuscripts are in Rome, in the Vatican Apostolic Library, in Portugal, in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, and in the United States of America. [6]

Ethiopians started three years after the defeat at Magdala to demand restitution but to no avail. In later years AFROMET (Association For the Return of the Magdala Ethiopian Treasures) has been active in attempts to secure the return of their treasures but without much success. Professor Richard Pankhurst, a British historian living in Ethiopia and a leading member of Afromet, wrote a lot about their struggles. [7] Answers they have received constitute a veritable catalogue of insults from European universities and other institutions holding Ethiopian treasures:

- The treasures are better protected in Europe

- The treasures are seen by more persons in Europe than if they were to be returned to Ethiopia

- Scholars still need to work on them

- Manuscripts are too old to travel

- Ethiopian museums do not have the security and environmental conditions that UK museums have.

In the context of the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Magdala, Tristram Hunt, Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, informed Art Newspaper that they had made “a clear statement to the ambassador, saying that if Ethiopia is interested in pursuing the long-term loan of the Magdala items we would stand ready to assist.”

Most of the statements by the director of Victoria and Albert Museum regarding the looting of Ethiopian artefacts at Magdala can be easily shown to have no solid basis and are generally tendentious, favouring imperialist aggression and denying the African peoples their human right to independent cultural development and the use of their own cultural artefacts.

Ethiopian Processional cross, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom.

Hunt said there were a number of reasons why a simple return was not possible, including legal difficulties around deaccessioning and the “philosophical case for cosmopolitanism in museum collections”. Hunt does not specify what legal difficulties are around deaccessioning. It is well-known that when the museums so desire, they find a way to avoid the various legal rules. The British Museum is known to have at occasions sold Benin artefacts despite the deaccession problem often invoked when the problem of restitution of Benin bronzes come up. [8] These alleged legal rules are rules of British law and cannot be invoked at the level of International Law to defeat the legitimate claims of other states.

And what does Hunt mean by “philosophical case for cosmopolitanism in museums?” This cosmopolitanism is in substance the same as the pretext of the so-called “universal museums”, later termed “encyclopaedic museums”, to present all cultures in their museums. This has never been accepted, especially by those countries whose looted artefacts are detained with the pretext of universalism. [9]

Hunt also declared “It behoves an institution like the V&A to reflect on this imperial past, to be open about this history and to interpret that history.”

“We should not to be afraid of history, even if it is complicated and challenging. As an institution, we should have the bravery to deal with it.”

This gives the impression that Hunt is particularly bold in dealing with the history of their museum and not being afraid of history. But most of their subsequent statements show they are unwilling to face the history of the looted artefacts in their museum and return them to the rightful owners. Mentioning simply the history of looting but not drawing a conclusion that those wrongs of the past should be corrected, is not particularly brave. Many before them have taken similar positions.

As custodians of a number of important Ethiopian objects taken from Magdala by the British military 150 years ago, we have a responsibility to celebrate the beauty of their craftsmanship, reflect on their modern meaning, and shine a light on this collection’s controversial history.

This is a cynical statement of a particularly painful kind. They are “[celebrating] the beauty of their craftsmanship”, which they deny to the Ethiopians by detaining their artefacts. It is a self-imposed duty for holders of looted artefacts. That “craftsmanship” is not British and is best celebrated by Ethiopians, the producers of the looted artefacts.

Hunt also told the Guardian: “You have to take it item by item and you have to take it history by history. Once you unpick the histories of the collections it becomes a great deal more complicated and challenging”. This statement shows the mentality prevailing in the museums holding looted artefacts of others. How does one take it item by item and history by history when the items all have the common history of having been looted from Magdala in 1868 by the British Army? It can only be a delaying tactic, which will not deceive any intelligent person.

A statement in The Times reflecting what Hunt said seems to me to be unbefitting of a museum director, however short they may be of arguments to resist restitution:

There are also questions over the legitimacy of claims regarding some of the items. For example, Emperor Tewodros II, who prompted the Battle of Magdala by taking a British missionary hostage after Britain’s refusal to help his empire in its battle with Turkish forces, is known to have seized some of the treasures British forces subsequently looted from other areas of Africa.

To say that some of the artefacts the British stole from Tewodros may have been stolen from other African countries, clearly is the lowest point of argumentation. It is like telling a court that the object you stole from a shop may have been stolen by the shop-manager from another place. This shows the poverty of arguments left in the arsenal of the universalists/encyclopaedists/cosmopolitans.

Ethiopian cross, Victorian and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom.

The absurdity of looters or their successors proposing to loan to the original owners the very objects looted from them is reached when Hunt declares that the Victoria and Albert Museum would also seek legal guarantees that the objects would be returned promptly. Knowing that the objects they are apparently loaning to Ethiopia are looted, there is apprehension that when the objects reach the owners they may decide not to return them. The museum is therefore asking the Ethiopian government to avert the usual course of justice: when looted/stolen objects are discovered they are seized for return to their owners.

What the museum is seeking is to pervert justice by creating an exception to the rule and grant those looted objects immunity from seizure. But it is the same government that has been seeking for years the restitution of the Magdala treasures. One can see the divisions that must arise in the Ethiopian society and in the government when they are not united in saying no to legalising robbery. The looters are proposing to the owners that when the looted objects reach the territory of the owner, they should not seek to keep them. Very interesting cases could arise if Ethiopians make use of the legal remedies available to owners whose properties have been stolen and later discovered. The divisions and tensions such matters may cause in an African state can be easily imagined.

There are several newspaper reports and headlines stating that Tristram Hunt does not agree with Macron’s approach to restitution of African artefacts:

“Don’t return all looted museum artefacts to Africa”, says V and A director Tristram Hunt. - The Times, April2018.

“President Macron of France is being simplistic with his drive to return all museum objects looted from Africa, the head of the Victoria and Albert Museum has said”-The Times, April 2018.

“Tristram Hunt said that Mr. Macron was wrong to adopt a guilty all” approach to the restitution of controversial artefacts…

“This is a step- by -step, item-by item process, he said. To have a Macron-style ‘all guilty’ approach is a very reductive approach because you have to take into account the history of each item.”

“…but Hunt says that outright restitution is not on the table. Nor is a President Macron style gesture that would include the hundreds of Ethiopian artefacts in other UK public collections including the British Museum, the British Library and the Royal Collection at Windsor”—news.artnet.com

The statements attributed to Tristram Hunt regarding President Macron’s declaration of 28 November 2017, at Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, are, to say the least, very surprising. First, let us look at Macron’s statement regarding restitution of African artefacts. Macron who was speaking before an audience of university students in Ouagadougou declared:

“…I cannot accept that a large part of cultural heritage of several African countries is in France. There are historical explanations for that, but no valid justifications that are durable and unconditional. African heritage cannot only be in private collections and European museums. African heritage must be highlighted in Paris, but also in Dakar, in Lagos, in Cotonou, this will be one of my priorities. I want conditions to be met within the next five years for the temporary or permanent restitution of African heritage to Africa.” [10]

Ethiopian cross, Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Where does Hunt get the idea that Macron was proposing to return all African artefacts in Europe to Africa? Macron referred specifically to African artefacts in France. When Macron says that African artefacts must be shown not only in Paris but also in Dakar, Lagos, and Cotonou, they assume that these artefacts would be available in Europe as well as in Africa.

Where is the alleged “all guilty approach” of Macron? Macron has set up a committee to examine the issues so their approach is neither simplistic or an “all guilty” approach. [11]

So why does Hunt make such outrageous exaggerations of Macron’s intentions?

I can only surmise that they are using an old weapon from the arsenal of the high priests of “universalism” when confronted by an opponent. They exaggerate the opponent’s statement to such an extent that they appear so ridiculous that there is obviously no need to consider the valid points they may be making. When exaggeration does not achieve its effect, insults are called in to create such a situation that no reasonable discussion is possible. [12]

Notwithstanding the unfortunate misinterpretations by Hunt and company of the declaration of President Macron, one should not underestimate the possible effects of that statement by the French statesperson. By their historic declaration, Macron has swept away any justification that the universalists may have had in defending looted African artefacts held in Western countries against the wishes of the African peoples. “Universalism”, as far as it was considered sufficient justification for holding looted artefacts of others, is finished and can convince no more and would come under considerable pressure from Africans and Asians, supported in their demands for restitution by uncountable United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO)/United Nations resolutions. Substitution of “universalism” by “cosmopolitanism” will not suffice if both concepts are used as justification for holding artefacts of others.

The relationship between African states and Western states regarding looted artefacts would have to be redefined. Macron’s ideas would have a chance of redefining this relationship insofar as it would be based on general agreement between States. It would have to exclude any pretention of African objects being loaned to African states. Rather, it would be acceptable as far as it reflects the historical fact that Europeans illegally and violently looted African artefacts and that, in the new era, these objects, for practical reasons, have been given to the guardianship of certain European states with ownership residing with the original African owners who can collect them in due course.

Whether they realise now or not, European states such as Belgium, Britain, Germany, the Netherlands and the rest will soon come under tremendous pressure to follow the policy of Macron which is, in many ways, the logical follow up to the process of independence started some 58 years ago when the African states gained independence. An independent state surely must have control over its cultural artefacts.

How is one to understand the offer of loan of looted Ethiopian objects to Ethiopia?

Since when are looters and their successors authorised to make loans of looted or stolen objects to the owners? Common sense revolts against such statements that seek to revoke or suspend normal logic and common intelligence.

The offer of a loan of Ethiopian artefacts looted by Britain is simply an insult to Ethiopians and all Africans. Tristram Hunt is repeating the same insulting remarks that were common some decades ago that we thought we had left behind. Those who looted Ethiopian artefacts with violence 150 years ago are now generously offering to loan them to the original owners. This follows a similar insulting offer to the people of Benin to set up in Benin City an exhibition of looted Benin artefacts, with ownership remaining with the Western museums that have been holding them illegally and illegitimately since the violent invasion by British forces in 1897 and the looting of more than 3500 Benin artefacts. [13] Who then are the owners of the artefacts? The original owners attacked by an invading foreign army or the foreign army and its successors?

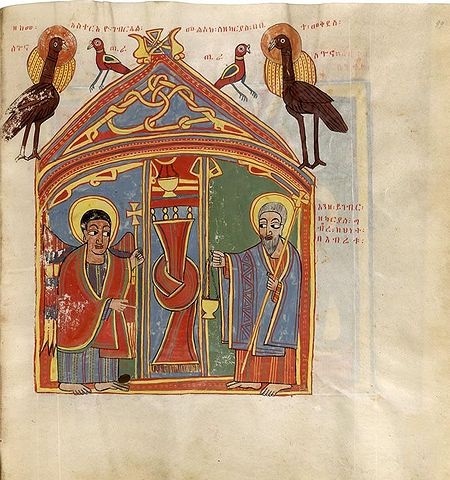

British Library Or. MS 481, f.110v - Christ in Glory, commissioned by Emperor Iyasu I Yohannes of Ethiopia for use in his royal city of Gondar. Wikimedia Commons.

Questions that need to be answered about proposed loans:

- What is the price of the loan?

- Who pays for transport and related costs?

- Who pays for insurance of the objects during transport?

- Will insurance be with a British or Ethiopian company?

- Who pays for security/insurance when the objects have landed?

- What will be some implications of acceptance of a loan of looted Ethiopian artefacts?

By accepting a loan of their own artefacts looted by the British, the people of Ethiopia would be renouncing their right to seek the restitution of the artefacts looted in 1868 by an invading British army at Magdala. They would thereby acknowledge British ownership of those artefacts looted in 1868. They will be stopped under English law from arguing later that the British were not the owners of the objects transported by 15 elephants and 200 mules after the defeat of Emperor Tewodros.

Even though other African peoples and states would not be involved in discussions over a proposed loan and thus have no means to influence decisions reached, patterns set up by Ethiopian arrangements would affect them. We should remember that Ethiopia has one of the best claims to recover looted artefacts. Should they be pacified with a loan of their own violently looted artefacts, countries like the Republic of Benin, Congo, Cameroon, Ghana, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and others would have serious difficulties to obtain restitution from Western states. The prestige of Ethiopia is extremely high, and it is not by accident that the Organisation of African Unity [and its successor the African Union] chose Addis Ababa as their headquarters.

Western states and museums would be the great beneficiaries of any scheme of loans of our own looted artefacts, The West needs no longer to have a worried and bad conscience that it has not returned African artefacts looted with violence during the colonial and imperialist period despite the claims of African peoples for their return. It would be said that the west has returned the artefacts on loan.

The moral and political pressures from international organizations such as the United Nations, UNESCO, and International Council of Museums (ICOM) would have been considerably neutralised or at least reduced without the West having to return the artefacts as required by countless United Nations/UNESCO resolutions.

The poverty of African museums in terms of numbers and quality of African artefacts in their possession would have been sealed forever. Where else can they obtain African artefacts of quality if not from those who looted and stole our artefacts in the colonial period?

If Ethiopia fails to achieve the restitution of its artefacts violently looted in 1868 by the British, there would be no hope of possible restitution of African artefacts in future.

We do not know how much the British would benefit financially from loans of looted Ethiopian artefacts to Ethiopia but if we consider what can be done in the question of insurance, we can imagine the extremely high premiums to be paid and the relevant insurance made with a British or American company and not with an Ethiopian or Nigerian company.

Should loans, instead of unconditional restitution, be accepted by African states and peoples, they would always have doubts about the legal status and the moral values of such loaned looted objects. Future generations would not know what to make of such objects. Youth would be more than confused about the historical value of such artefacts. Ethiopian youth would read somewhere that these objects are Ethiopian but will also read that these objects are loans from Britain. Who then really made them? That element of national pride would be lost or at least minimised. How could they be proud of a product the exact origin of is in doubt and possibly listed as a loan from Britain? Another form of aid?

Above all, the loan of a looted object to its original owner contradicts the nature of restitution as a process of reconciliation. Returning an artefact to the deprived owner is a gesture meant to indicate that whatever may have been the controversy between the parties, the time has now come to put away such differences and to forge a new future relationship, free from the problems of the past. A loan, short-term or long-term, always indicates that the past is not gone and that there exists the possibility that the matter could be re-opened if one side or the other does not fulfil its obligations. Thus, the loan itself can become a source of new conflict, irrespective of the causes of the original conflict that led to the looting of the object in the first place. Considering the nature of colonialism and the wounds and problems it left for the colonised, it is surely only a very tiny but important gesture for the former coloniser to return a looted artefact. Reconciliation between Africans and Europeans cannot be achieved without some price, considering all that the colonisers gained through the exploitation of the human and natural resources of the colonies. A healing process, which is what restitution essentially is, cannot be achieved if Europeans are not even willing to make such a gesture. If the Belgians, British, Dutch, French, Germans, Italians and others are not yet ready to make such tiny concessions, they should not start at all. They open such wounds and leave the Africans again traumatised and more discouraged than before, with no ground to hope for better relations in future. When I read what Hunt and others are saying, I have the impression they do not understand what the loss of religious and cultural symbols means to Africans. The mercantile calculations of the European museum directors are miles away from the emotions and memories such matters raise with Africans.

European states and their museums have generally not revealed their true reasons for rejecting straightforward restitution and preferring loans, short or long term.

To accept restitution would imply that the original looting and detention of the artefacts were wrong and without legal basis. This admission could in turn offer basis for any claims of compensation for loss of usage of the objects and for loss of earnings, damage to property and for loss of human lives. The earnings of the Western museums, due to tourism, copyright fees, exhibition loans profit and other benefits, could also be discussed.

We do not envy the Ethiopians who will have to distinguish between the following:

- Ethiopian artefacts in Ethiopia that belong to Ethiopia and have not been looted,

- Ethiopian artefacts in Ethiopia that have been looted and returned but do not belong to Ethiopia since they are on loan from a foreign country,

- Ethiopian artefacts that have been looted and are in a foreign country but may be returned on loan, and;

- Ethiopian looted artefacts in a foreign country that will not be returned even on loan because they are so precious, and the foreign country argues that Ethiopia does not have the proper facilities. Think of the precious Ethiopian books and manuscripts. We must remember also that Ethiopian crosses and historical/religious manuscripts are found in many institutions in the West that have shown no inclination to return any. Indeed, some Westerners who are perhaps closer to God than we are, seem to believe they have a God-given duty and right to hold on to the artefacts of others notwithstanding the moral principle that “Thou shall not steal”.

Whenever Africans have asked for the return of their looted artefacts, the West has responded that the Africans are trying to rewrite history. But what are they doing when they boldly propose a loan of the looted objects? In effect, they are rewriting history. They are reinventing histories of the artefacts concerned. They are presenting themselves as owners of the objects to be loaned. They are reinventing the history of each object when they pretend, contrary to the recorded history of the object, that they are owners. Tristram Hunt says one should face history. Is the Victoria and Albert Museum facing history when, contrary to the true history of the object which they admit, they present their museum as the owner of the objects that they are ready to loan. From successors of the looters at Magdala, they now appear as owners of the looted objects. What then are the Ethiopians, successors to Tewodros who are deprived of their treasures?

After having spent considerable time on issues of restitution of looted African artefacts, we would advise leaders of Egypt, Ethiopia, the Republic of Benin, Nigeria, and all other African states not to accept loans of their own looted artefacts. They have a right to complete unconditional restitution of the artefacts that were looted and stolen by Western states. They have the right to demand compensation for deprivation of the use of the artefacts for hundred years and the destruction of properties often caused by colonial aggression in acquiring those artefacts. The number of Africans decimated in such aggressions are not recorded but can be estimated from the amount of colonial violence experienced in such situations. They should not let expediency and short-term advantages prevail against their historical task to recover their national treasures illegally and illegitimately seized by conquering imperialist powers.

Some people in Ethiopia and elsewhere may be thinking or saying that a loan is a step in the right direction. Do they know the direction? Have they any indicia for the direction of the European states and museums? A loan is not a necessary step towards unconditional restitution. A loan having conditions attached must not necessarily end in unconditional restitution. There are no examples in our relations with Europe in the last 500 years that justify such an opinion. Have any of the European states and museums proposing loan of artefacts stated the conditions under which the loan might be turned into outright unconditional restitution?

If, after weighing all the relevant information of the historical background and considering the permanent and constant violation of the human rights of Ethiopians to use their own artefacts, Westerners feel they cannot return the looted artefacts unconditionally to where they were stolen, they should be told directly and in unmistakeable language that a loan, long or short term, is not the correct solution for looted artefacts. We should leave matters where they are until the holders are willing to return the artefacts without conditions. Existing relations should not be complicated with loans. Nigeria has already called for unconditional return of all looted Nigerian artefacts. [14]

If on the other hand, Europeans are keen to make genuine loans of European art works to African States and their museums, we would welcome this gesture wholeheartedly. We could do on the African continent with some masters of European art; Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Botticelli, Rembrandt, Raffael, Bellini, Van Gogh, Goya, Velazquez, Manet, Monet, etc. We would be even more grateful if Europeans loaned us works of modern artists such as Arman, André Derain, Georges Braques, Jacob Epstein, Erich Heckel, Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee, August Macke, Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein, Max Ernst, Constantin Brancusi, Alberto Giacometti, Henri Matisse, Joao Miró, Henry Moore, Amedeo Modigliani, Maurice de Vlaminck and others who have obviously been influenced by African art. The return of African artworks from abroad and the presence of European masters would work as catalyst for our young artists. We could experience a great surge of artistic talent and creativity such as the continent has not seen for a while. Our youth would have the sources of inspiration that young artists everywhere have: the presence of the works of acknowledged masters of their own culture and the works of masters of other foreign cultures.

We will also need loans of European art if we want to establish world museums since the usual way in which those museums acquired thousands of artefacts, looting with violence, is no longer available to us. We would want to create genuine world museums, in the true sense of the word ‘world’, i.e. where every culture of the world, including European culture, is represented and not in the present perverse sense in which European culture is excluded and the museums are regarded as mainly citadels for looted artefacts from non-European peoples.

If, after one hundred and fifty years since Magdala, there are influential persons in the British hierarchy who do not accept that stealing Christian crosses of others is not right, then the rest of us cannot do more than either wait and pray that this profound revelation be soon perceptible to all in Great Britain or bring more pressure on the British rulers to do the right and honourable thing.

“He deeply regretted that those articles were ever brought from Abyssinia and could not conceive why they were so brought. They [the British people] were never at war with Abyssinia... he [Gladstone] deeply lamented, for the sake of all concerned, that those articles, to us insignificant, though to the Abyssinians probably sacred and imposing symbols, or at least hallowed by association, were thought fit to be brought away by the British army”—William Gladstone. [15]

* Kwame Opoku an independent commentator on African cultural affairs

British Library Add. MS 59874 Ethiopian Bible - Annunciation to Zechariah (Ge’ez script)

Notes

1. Henry M. Stanley, Magdala: The Story of the Abyssinian Campaign,1866-67. Being the Second Part of the Original Volume Entitled “Coomassie and Magdala”, Leopold Classic Library,1896, p. 156.

2. U.K. Museum Offers Ethiopia Long-Term Loan of Looted Treasures ...

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/.../v-and-a-ethiopian-treasure.htm... -

Looted Ethiopian treasures in UK could be returned on loan | Art and ...

https://www.theguardian.com/.../looted-ethiopian-treasures-in-uk-...

Ethiopia Receives Long-Term Loan of Looted Artifacts from London's ...

https://www.artforum.com/.../ethiopia-receives-long-term-loan-of...

V&A opens dialogue on looted Ethiopian treasures | The Art Newspaper

theartnewspaper.com/.../v-and-a-opens-dialogue-on-looted-ethio...

BBC Focus on Africa (100418) - Should looted Ethiopian treasures be ...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=psAn8Dffjrk

3. K. Opoku, afrikanet.info: Ethiopia: The Way in Demand for Restitution of African ...

www.afrikanet.info/.../ethiopian-president-shows-the-way-in-dem...

When will the West return Ethiopia’s treasures - Elginism

www.elginism.com/similar-cases/...ethiopias-treasures/.../1335/

African Queens - Kwame Opoku - Ligaliwww.ligali.org/.../African%20Queens%20-%20Kwame%20Opok.

4. R. Pankhurst, Magdala and its loot, AFROMET Home page

http://www.afromet.info/about_us_action.html

https://www.modernghana.com/.../when-will-britain-return-loote...

5. http://www.britishmuseum.org

Writing about the auction at Magdala, Henry Stanley states:

“Mr. Holmes, as the worthy representative of the British Museum, was in his full glory. Armed with ample funds, he outdid all in most things; but Colonel Frazier ran him hard because he was buying for a wealthy regimental mess-11th Hussars- and when anything belonging personally to Theodore was offered for sale, there were private gentlemen who outbid both.”

Mr Holmes secured many interesting articles. Henry Stanley, op. cit. p.168.

6. See Annex I

7. Bibliography | Richard Pankhurst

https://richardpankhurst.wordpress.com/bibliography

8. British Museum sold precious bronzes | UK news | The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2002/mar/.../education.museum...

BBC News | ARTS | Benin bronzes sold to Nigeria

news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/1896535.stm

British Museum Sold Benin Bronzes - Forbes

https://www.forbes.com/2002/04/03/0403conn

9. K. Opoku, Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums: Singular Failure ..of an Arrogant Imperialist Project.

https://www.modernghana.com/.../declaration-on-the-importance.

10. ‘… je ne peux pas accepter qu’une large part du patrimoine culturel de plusieurs pays africains soit en France. Il y a des explications historiques à cela mais il n’y a pas de justification valable, durable et inconditionnelle, le patrimoine africain ne peut pas être uniquement dans des collections privées et des musées européens. Le patrimoine africain doit être mis en valeur à Paris mais aussi à Dakar, à Lagos, à Cotonou, ce sera une de mes priorités. Je veux que d’ici cinq ans les conditions soient réunies pour des restitutions temporaires ou définitives du patrimoine africain en Afrique’.

Le discours de Ouagadougou d’Emmanuel Macron. Le Monde Afrique,29.11.2017 Restitution du patrimoine africain.

https://www.modernghana.com/news/.../macron-promises-to-retu...

macron promises to return african artefacts held in ... - No Humboldt 21

www.no-humboldt21.de/.../Opoku-MacronPromisesRestitution.p..

11. After a Promise to Return African Artifacts, France Moves Toward a Plan

https://www.nytimes.com/.../france-restitution-african-artifacts.ht...

French President Hires Experts to Make Plans for Repatriation of ...

https://www.artforum.com/.../french-president-hires-experts-to-m...

12. This technique of exaggerating the statement of an opponent so that one does not have to examine his arguments can be illustrated by an exchange of letters by Philippe de Montebello and Kwame Opoku, published in Afrikanet.info

Opoku wrote an article entitled “Is legality a viable concept for European and American museum directors?” http://www.afrikanet.info/index. suggesting that ‘Those museums that are holding a large quantity of Benin pieces, British Museum, 700, Ethnological Museum, Berlin, 600, should return some of these to Nigeria’. Phillipe de Montebello Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, renders Opoku’s suggestion as follows: “Dr. Opoku believes all Nok, Ife, and Benin pieces outside of Nigeria should be returned to Nigeria; that all works produced on its territory should remain there”. http://www.afrikanet.info/.

See Kwame Opoku’s response to Philippe de Montebello - AFRIKANET ...

www.afrikanet.info/archiv1/index.php?option=com...task.

Africa – Illicit Cultural Property

illicitculturalproperty.com/tag/africa/

tomflynn: Ex Africa semper aliquid novi

tom-flynn.blogspot.com/2008/.../ex-africa-semper-aliquid-novi.h..

Kwame Opoku responds to Philippe de Montebello - Elginism

www.elginism.com/...opoku...to-philippe-de-montebello/.../1147/

Consider how MacGregor insulted the Greeks and his predecessor’s disgraceful behaviour towards the unforgettable Melina Mercouri.

Amazing Director of British Museum: A Gratuitous insult on cultural ...

https://www.vanguardngr.com › The Arts –

The Amazing Director of the British Museum: Gratuitous Insults as Currency of Cultural Diplomacy?

https://www.modernghana.com/.../the-amazing-director-of-the-br..

K. Opoku – Respect and disrespect in restitution of cultural artefacts..

https://www.toncremers.nl/kwame-opoku-respect-and-disrespect-i..

13. K. Opoku, We Will Show You Looted Benin Bronzes But Will Not Give Them Back ...https://www.modernghana.com/.../we-will-show-you-looted-beni...

14. K .Opoku, Nigeria Demands Unconditional Return of Looted Artefacts: A Season .of Miracles?..

https://www.modernghana.com/.../nigeria-demands-unconditiona...

15. During discussion in the British House of Commons, on 30 June 1871, the British statesman, William Gladstone, commented on the loot from Magdala, observed, as quoted in “Hansard”. Richard Pankhurst, The Loot from Magdala, 1868: Some Historical Ideas of Repatriation, www.tigraionline.com/loot_from_Magdala.html

Annex I

Institutions holding Ethiopian manuscript collections (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethiopian_manuscript_collections)

2 Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

5 Cambridge University Library, Cambridge

6 Chester Beatty Library, Dublin

7 Edinburgh University Library, Edinburgh

8 Gunda Gunde Monastery, Tigray Region

9 Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, Collegeville, Minn.

10 Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa

11 John Rylands Library, Manchester

12 J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

13 National Archives and Library of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

14 Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey

17 University of Oregon, Museum of Natural and Cultural History

19 Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

20 Wellcome Collection, London

Annex II

AFROMET List of Missing Ethiopian Treasures Held by Britain

Missing treasures

http://www.afromet.info/treasure/archives/cat_missing_treasure.html

Abuna’s crown

The British Government has already resisted one attempt to restore this gold crown to Ethiopia in 1923.

Adulis fragments

Captain W. Goodfellow of the Royal Engineers made some quick excavations in Adulis (in modern day Eritrea) in the aftermath of the seige, from May 28 to 9 June 1868. They sent two cases of fragments home including “a bas-relief representing a cross”, suggesting an early Christian site.

British Library manuscripts (349)

Magdala manuscripts make up almost half of the British Library’s collection of Ethiopian parchments. They were originally stored in the British Museum Library which was recently incorporated into the British Library.

Divided drum

A ceremonial drum was seized at Magdala and sliced into three pieces, so that it could be handed out as battle honours to three regiments involved in the raid. The present day descendants of those regiments have refused to return the drum pieces, despite appeals.

Dundee scroll

This scroll, inscribed in red and black ink, is currently in the collection of the University of Dundee Museum.

Edinburgh University’s manuscripts (5)

Edinburgh University Library has 11 manuscripts written in Amharic or Ge’ez. Three of them are positively linked with Magdala in the catalogue. Two others are dated from the same era.

Edinburgh’s torn manuscript

This double page was torn out of a manuscript of the Miracles of Mary, found in one of the churches at Magdala. The page, which is beautifully illuminated on both sides, is listed as a “fragment” and kept in the National Archives of Scotland in Edinburgh.

Gold chalice

Check back for more information on the golden ecclesiastical chalice, currently held in London’s Victoria & Albert Museum.

Halifax miscellaneous

The Duke of Wellington’s Regimental museum has a number of smaller items from Magdala in its collection. They include a fly-whisk with a ram’s horn for a handle, an ammunition belt, complete with powder and shot, and a sword.

John Irving’s loot

Ensign John Beaufin Irving, of the 4th King’s Own regiment, reportedly broke into Magdala single-handedly on the eve of the final battle. According to regimental accounts, they emerged with “some sacred vessels and a manuscript”. Apparently his family still has “various trophies of the campaign”.

King’s Own Bible

The 4th King’s Own regiment returned with a number of battle trophies from the campaign, including what regimental records describe as “an illuminated bible”.

Kwer’ata Re’esu Icon

This painting, showing Jesus Christ looking downward, was taken from Magdala by Sir Richard Holmes, representative of the British Museum on the expedition. They did not disclose his acquisition during his lifetime. The Kwer’ata Re’esu, purchased in London in 1950, is now the property of a Portuguese collector who wishes to remain anonymous.

Lancaster miscellaneous

The King’s Own Royal Regiment Museum has an exhibit dedicated to the Abyssinian Campaign. The case includes an illuminated bible and a large number of smaller exhibits.

Lancaster’s crosses

The King’s Own Royal Regiment took four processional crosses from Magdala. They are currently on display in The King’s Own Regimental Memorial Chapel in Lancaster Priory.

Manchester’s manuscripts (42)

Manchester’s John Rylands University Library picked up 42 Magdala manuscripts in 1901 when it bought a private collection of papers owned by the 26th Earl of Crawford, James Ludovic Lindsay.

Panel of tablet-woven silk

This ecclesiastical cloth, part of a triptych that would have screened off the inner sanctum of a church, is currently on display as part of the British Museum's African collection.

Reed shirt

Check back for more details on this this shirt, apparently made out of a delicate mesh of reeds, currently kept at the Duke of Wellington’s Regimental museum in Halifax, England.

Shield with lion’s mane

This hide shield with velvet and silverwork, with a lion’s mane pendant, is currently on display as part of the British Museum’s African collection.

Skull

Mr W. Jesse, the expedition's official Zoologist, from the UK's Zoological Society, records finding an “aboriginal skull”.

Stanley’s loot

Henry M. Stanley, on the verge of a career as an African explorer, was at Magdala, working as a journalist. After the fall, they boasted of acquiring a shield, a “royal cap”, part of Emperor Theodore’s tent and a decorated, be-jeweled saddle.

Studland’s cross

A processional cross taken at Magdala is currently kept at the Norman church of St Nicholas, in Studland, in the English county of Dorset. According to one report, the church rector at the time obtained permission from Emperor Haile Selassie to keep it.

Ta’amra Maryam, 33 Miracles of the Virgin Mary and Document concerning a conciliation

This combined manuscript went on a remarkable journey after it was taken by a British soldier at the battle of Magdala. The soldier sold it, along with a number of other Magdala papers, to London’s Quaritch bookstore, a dealer in antique manuscripts. The British Museum looked into buying it but was in effect outbid by Lady Meux, a flambouyant figure in Victorian London, known for her collection of ancient Egyptian artefacts. She left it to the descendants of Menelik II, Emperor of Ethiopia, in her will.

Tabots (9)

The British Museum currently holds nine tabots taken in the aftermath of the battle of Magdala. Given the sacred nature of the tabots, Museum staff have promised never to put them on display. The gesture is appreciated. But it raises the question of why the Museum is insisting on holding on to exhibits that it can never show.

Tents (2)

Check back for more information on these marquee-style tents, currently held in the Museum of Mankind in London.

Throne cloth

Emperor Tewodros’s magnificent throne-cloth was taken by Captain Sandys Wason of the 33rd Regiment at Magdala. It was later donated to the regimental museum in Halifax, England.

Windsor Castle manuscripts (6)

Six magnificently illustrated ecclesiastical manuscripts from Magdala are currently part of the Queen of England’s personal collection in the Royal Library in Windsor Castle.

Returned Treasures

Compiled by AFROMET

http://www.afromet.info/about_us_action.html

Edinburgh’s Tabot

One of at least 11 Tabots (consecrated altar slabs) seized at Magdala by British soldiers. This one was taken by a Captain Arbuthnot of the 14th Hussars who may have been an Aide de Camp to General Napier, the leader of the expedition. On return to Britain, recognising the religious significance of the artefact, they presented the Tabot to St. John's Episcopal Church at the west end of Princes Street in Edinburgh.

Great seal

Emperor Tewodros’s great seal was returned by the UK’s Queen Elizabeth II during her state visit to Ethiopia in 1965. She also returned the Emperor's royal cap.

Kebra Nagast

An Ethiopic manuscript of the Kebra Nagast, or Glory of Kings (the national epic), was returned by the British Museum in 1873 at the request of Emperor Yohannes IV.

Maggs Tabot

This Tabot was handed over in Addis Ababa on July 1, 2003 by Dr Ian MacLennan, an Irish doctor who spotted it in a London book dealer's catalogue of Ethiopian manuscripts and artefacts.

Psalms of David

This hand-written copy of the Psalms of David was put up for sale in Maggs bookdealers, Mayfair, London by a private collector. Members of AROMET UK spotted it, raised £750 to buy it, and sent it back to Addis Ababa in the safe hands of Dr Richard Pankhurst in September 2003.

Royal cap

Emperor Tewodros’s royal cap was returned by the UK's Queen Elizabeth II during her state visit to Ethiopia in 1965. She also returned the Emperor's great seal.

Tewodros’s “barbaric” crown

The British Governemt agreed to return this Magdala crown to Ethiopia during a state visit by Ras Tafari Makonnen (the future Emperor Haile Sellassie, who was then Regent and Heir to the Throne) in 1923.

Tewodros’s Amulet

The Amulet which Emperor Tewodros of Ethiopia was wearing on 13 April 1868, the day of his dramatic suicide at Magdala, was returned to Ethiopia on 28 September 2002.