Mass Racial Incarceration for Profit

This article is transcription from a lecture, which Abayomi Azikiwe delivered at the First Unitarian Universalist Church of Detroit, Michigan on Sunday 18 February 2018. Abayomi Azikiwe presented the message for the day on the history and contemporary significance of mass incarceration and the enslavement and continued national oppression of the African American people.

The United States faces profound challenges in the areas of race relations, class exploitation, the rights of immigrants, women and other marginalised groups, the threat of world war and other calamities. Much of the discourse within the corporate and government-sponsored media does not provide solutions to the monumental problems we are grappling with.

Repeatedly President Donald Trump states that the economy is booming, with unemployment being at its lowest levels in history accompanied by skyrocketing business confidence in regard to investment and job creation. These claims are not accurate. Even if they were it would not wipe away the tears of family members and friends of those killed recently in the school shooting in South Florida.

The millions who are suffering in our society from racism and all forms of oppression cannot gain solace from the enrichment of a minority of the population. Here in the city of Detroit, Michigan, the conditions and concerns of the majority of African American population go unheeded. The elusive emphasis by the powers that be is placed on making Detroit whiter and wealthier.

Thirteenth Amendment and continuance of African slavery

This year represents the 150th anniversary of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, which provided citizenship to African people who had been subjected to enslavement for two-and-a-half centuries.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 passed by Congress was designed to provide the same guarantees related to due process and non-discrimination, empowering the federal government and its three branches of the executive, legislative and judicial structures to enforce these measures and to take action against persons or institutions which sought to deny African people inherent privileges.

The Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution was passed by Congress and ratified later in December of 1865. This measure was designed to legally free Africans from slavery. However, a careful reading of the Thirteenth Amendment illustrate language which both frees people from involuntary servitude yet making exceptions under the guise of criminal conviction and sentencing.

Section one of the Thirteenth Amendment states “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, nor any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Then Section Two states: “Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

This contradictory character of the Thirteenth Amendment sheds light on the utilisation of the criminal justice system in perpetuating bondage for the purpose of racism and class exploitation.

Slavery is an economic system. It is a mode of production designed for the maximisation of profit for the few landholding gentry. It was the Triangular Trade and chattel slavery, which provided the wealth that spawned an industrial monopoly capitalism beginning in the 19th century.

Two African historians documented this transformative economic process during the 1930s and 1940s: Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois of the US and Dr. Eric Williams of the Caribbean island-nation of Trinidad and Tobago.

Du Bois in his pioneering work entitled Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880, published in 1935, said that: “Slowly but mightily these black workers were integrated into modern industry. On free and fertile land Americans raised, not simply sugar as a cheap sweetening, rice for food and tobacco as a new and tickling luxury; but they began to grow a fibre that clothed the masses of a ragged world. Cotton grew so swiftly that the 9,000 bales of cotton, which the new nation scarcely noticed in 1791, became 79,000 in 1800; and with this increase, walked economic revolution in a dozen different lines. The cotton crop reached one half million bales in 1822, a million bales in 1831, two million in 1840, three million in 1852, and in the year of secession, stood at the then enormous total of five million bales” (Du Bois, 1935, p.10).

This same study continues,“As slavery grew to a system and the Cotton Kingdom began to expand into imperial white domination, a free Negro was a contradiction, a threat and a menace. As a thief and a vagabond, he threatened society; but as an educated property holder, a successful mechanic or even professional man, he more than threatened slavery. He contradicted and undermined it. (Du Bois, 1935,pp. 12-13).

Eric Williams published Capitalism and Slavery in 1944. This study focused largely on Britain and pointed to the direct trajectory of profit-making under the slave system and the rise of industry.

In chapter five Williams observes: “Britain was accumulating great wealth from the triangular trade. The increase of consumption goods called forth by that trade inevitably drew in its train the development of the productive power of the country. This industrial expansion required finance. We have already noticed the readiness with which absentee planters purchased land in England, where they were able to use their wealth to finance the great developments associated with the Agricultural Revolution” (Williams, 1944, p. 98).

Banking, insurance, shipping and manufacturing were all fuelled by the profits accrued from the super-exploitation of Africans. Consequently, the economic system of slavery provided the necessary social ingredients to build a new mode and relationship of production, being capitalism.

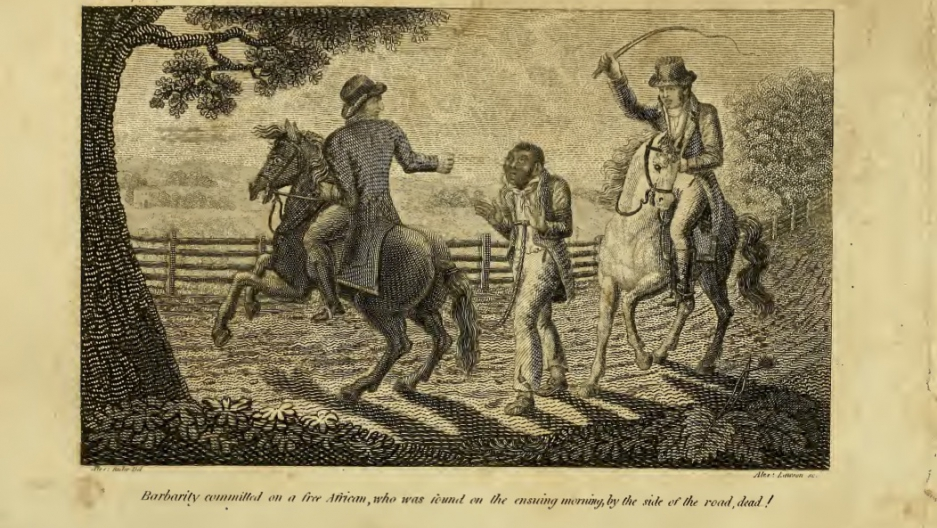

As slavery expanded in the South, both law-enforcement and correctional facilities took on added significance. From the 1820s to the 1850s, Washington, DC itself was a major base for private prisons, which held and later transported Africans to the slaveholding areas of the South (Taparata, 2016)

Although President Thomas Jefferson signed law provisions, which prohibited Atlantic Slave Trade in the US in 1807, human bondage continued. Inter-state trade in African people was expanding, as cotton became the major industry of production and export.

A major institution designed to facilitate the domestic slave trade was private prisons. The opponents of this practice sought to have it regulated or outlawed during the 1820s to the 1850s. However, the private prisons continued operations leading up to the Civil War from 1861-1865.

There were many cases of free Africans being arrested and later enslaved. This was the fate of Gilbert Horton who was arrested in 1826 and held for a month on charges of being a runaway slave. A Congressman from Pennsylvania, Charles Minor, criticised the use of private prisons to service the slave system during the Horton matter. Horton was not released until able to provide references from Poughkeepsie, which could substantiate that he was not a fugitive.

Many others were not so fortunate as to escape the slave traders. One African woman in 1816 being held in a private prison in Washington, DC became so distraught that she attempted to take her own life. Anna (as she is known) jumped from the third floor of a slave prison. These events prompted Virginia Congressman John Randolph to speak out against such institutions.

Randolph called for a committee to investigate the private prisons in the nation’s capital. Randolph conveyed the plight of Anna stressing: “A woman, confined in the upper chamber of a three story private prison, used by the slave dealers in their traffic, was driven to throw herself from the window upon the pavement.” (Randolph, no date)

Evan Taparata (2016) says: “Despite attention to private prisons in DC, substantive reform was elusive. In a renewed push to end the slave trade in 1848, Representative John Crowell of Ohio doubled down on the lack of oversight and visibility of private prisons. Crowell knew of a private prison near the Smithsonian Institute on the National Mall. The Smithsonian, Crowell noted, “was founded here for the diffusion of knowledge among men, and in full view of this Capitol, and the stripes and stars that float so proudly over it” (Cromwell, 1848).

Private prisons and correctional facilities

Having private prisons, as lucrative businesses at the service of chattel bondage did not end with the Civil War. Efforts to maintain African people as a principal source of free labour were maintained through a series of laws and social practices.

By 1877, the government under President Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew any semblance of national support for Black Reconstruction. The Ku Klux Klan and other white terrorist organisations were founded to restore the supremacy of the slaveholding class. African Americans continued to hold office in local and state structures within southern states such as Tennessee, South Carolina and North Carolina into the 1880s and 1890s. Overall there was very limited or no right held by African people that the white rulers respected.

The Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896 ruled that segregation was perfectly legal under the US Constitution. African Americans could be separated from whites on the basis that their facilities were equal to those of Europeans.

This remained the law until 1954 when the Brown v. Topeka case related to segregated public schooling was deemed a violation of US jurisprudence. Separate but equal was inherently unconstitutional said the Warren court. Subsequently though, almost nothing was done on the federal, state and local levels of government to breakdown Jim Crow.

It would take a Civil Rights Movement petitioning the courts for implementation of existing constitutional amendments and laws from the mid-1950s through the late 1960s along with mass protests, boycotts and urban rebellions which broke open the US political and social system. Further legislation in 1957 (Civil Rights Act), 1964 (Civil Rights Act), 1965 (Voting Rights Act) and 1968 (Fair Housing Act) added additional measures re-emphasising what had been enacted from the Reconstruction era of 1865 to 1875.

Taparata conveys: “Private interests continued to play a major role in the prison industry. African Americans arrested in the Jim Crow South faced the prospect of convict leasing, a system of labour in which states leased out prisoners to private contractors who were more interested in boosting profit margins than ensuring safe working conditions” (Taparata, 2016).

Douglas A. Blackmon documents the practice of forced slave labour during the late 19th and 20th centuries. Southern and Northern corporate magnates profited immensely from the continuation of slavery after the Civil War and subsequent constitutional amendments purportedly outlawing slavery and the systematic mistreatment of African Americans.

Blackmon paints a horrendous portrait of conditions facing the former enslaved Africans: “Under laws enacted specifically to intimidate blacks, tens of thousands of African Americans were arbitrarily arrested, hit with outrageous fines, and charged for the costs of their own arrests. With no means to pay these ostensible ‘debts,’ prisoners were sold as forced laborers to coal mines, lumber camps, brickyards, railroads, quarries, and farm plantations.. ‘Free’ black men labored without compensation and were forced through beatings and physical torture to do the bidding of white masters for decades after the official abolition of American slavery” (Blackmon, 2008).

Mass incarceration for profit (Post-Civil Rights era)

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) made no distinction between Civil Rights, Black Nationalism and Communism. Any effort aimed at elevating the status of African American was deemed to be subversive.

Organisations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. were investigated and destabilised right along with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panther Party (BPP). Systematic efforts were made through surveillance, the planting of slanderous material in the media and the framing of activists in concocted criminal plots were designed to both discredit and disrupt political activities.

With the assassination of Malcolm X (El Hajj Malik Shabazz) in February 1965, Dr. King in April 1968 and the imprisonment and exile of other African American leaders while criminalising their organisations, hampered the burgeoning struggle for genuine freedom and national liberation.

Municipalities such as Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland, Los Angeles, Gary etc., lost millions of job held by African Americans. This was compounded by the outright defeat of US imperialism in Southeast Asia by 1975. African liberation won significant victories in the late 1970s and early 1980s, which weakened the grip of imperialism.

African Americans are disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system. A recent study by the Sentencing Project documents this racialised system of incarceration where African Americans are subjected to slave labour conditions and torture.

An article published in The Guardian reveals that: “Black Americans were incarcerated in state prisons at an average rate of 5.1 times that of white Americans and in some states that rate was ten times or more. The US is 63.7 percent non-Hispanic white, 12.2 percent black, 8.7 percent Hispanic white and 0.4 percent Hispanic black, according to the most recent census”(Nellis, 2016).

The research was conducted by Ashley Nellis, a senior research analyst with the Sentencing Project, a Washington, DC-based non profit that promotes reforms in criminal justice policy and advocates for alternatives to incarceration.

New Jersey had the highest, with a ratio of 12.2 black people to one white person in its prison system, followed by Wisconsin, Iowa, Minnesota and Vermont. Overall, Oklahoma had the highest rate of black people incarcerated with 2,625 black inmates per 100,000 residents. Oklahoma is 7.7 percent black. Among black men in 11 states, at least 1 in 20 were in a state prison” (Nellis, 2016).

Overall the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) indicated that combined Black and Brown people constitute nearly 60 percent of the incarcerated population in the US.

The BJS’s Sentencing Project provides data over the last few decades. A report issued by them reveals: “Private prisons in the United States incarcerated 126,272 people in 2015, representing eight percent of the total state and federal prison population. New Mexico and Montana incarcerate over 40 percent of their prison populations in private facilities, while states such as Illinois and New York do not employ for-profit prisons. Data compiled by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) show that in 2015, 28 states and the federal government incarcerated people in private facilities run by corporations.” (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2015)

This report continues emphasising numbers supplied by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, stating: “21 of the states with private prison contracts incarcerate more than 500 people in for-profit prisons. Texas, the first state to adopt private prisons in 1985, incarcerated the largest number of people under state jurisdiction, 14,293.The federal prison system experienced a 125 percent increase in use of private prisons since 2000 reaching 34,934 people (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2015).

Implications of mass incarceration in privatised prisons

Placing people within correctional institutions for extended periods of time only benefits the racist capitalist system in the US. Methods of complete integration and the right to self-determination is the only solution to racial polarisation and economic exploitation. In recent years there has been a resurgence of activism within the prison population. Inmates have engaged in hunger strikes and work stoppages in protest against the dehumanising conditions they are living in on a daily basis.

Those of us concerned about eliminating racism and class exploitation must view the struggle of prisoners as an integral aspect of the movement to end injustice in the US.

*Abayomi Azikiwe is Editor for Pan-African News Wire

* This article is an edited version of Abayomi Azikiwe’s presentation on 18 February 2018

References

Blackmon, D.A. (2008) Slavery by Another Name: The Re-enslavement of Black People in America from the Civil War to World War II. Place: Unknown: Publisher: Doubleday.

Bureau of Justice Statistics, (2015). The Sentencing Project: Private Prisons in the United States [pdf] Bureau of Justice Statistics. Available at: https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/private-prisons-united-states/ [Accessed 28 February 2018]

Cromwell, J (1848) The slave-trade roots of US private prisons [online] Available at:

https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-08-26/slave-trade-roots-us-private-prisons [Accessed 28 February 2018]

Du Bois, W.E.D (1935) Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880. Place: Unknown : Publisher: Unknown.

Nellis, A (2016) Black Americans incarcerated five times more than white people – report. The Guardian. 18th June [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/jun/18/mass-incarceration-black-americans-higher-rates-disparities-report [Accessed 28 February 2018]

Randolph, J (n.d) The slave-trade roots of US private prisons [online] Available at:

https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-08-26/slave-trade-roots-us-private-prisons [Accessed 28 February 2018]

Taparata, E, (2016) The slave-trade roots of US private prisons [online] Available at:

https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-08-26/slave-trade-roots-us-private-prisons [Accessed 28 February 2018]

Williams, D., (1944) Capitalism & Slavery. United States: The University of North Carolina Press.