Working class: Achievements and the unfinished war for emancipation

What has the working class achieved so far in its war for emancipation? Are not the exploited of the earth encountering unfinished work in their struggles against the most experienced and resource-rich class the world has witnessed till today? These questions are apposite while examining the class struggle on the world stage.

Michael D. Yates has probed the questions in chapter 4 of his recently released book Can the Working Class Change the World?(Monthly Review Press, New York, October 2018). The chapter – “What hath the working class wrought?” – proclaims:

“A signal achievement of the working class and peasantry in the global South, both in those countries that made socialist revolutions and those that did not, is the assault they made upon colonialism and imperialism. Before substantive changes could occur in the lives of the masses of people, the control wielded by colonial powers had to be broken and imperialism had to at least be weakened. Workers and peasants did this throughout the impoverished nations of the world.”

No other class has made this achievement, has delivered this duty to millions of millions. It’s unprecedented. It’s historic. It’s a service to humanity, to the peoples of the world. Because imperialism and colonialism are scourges on the face of the earth, threats to the survival of life on this planet. The two – imperialism and colonialism – assault peace, and distort the lives and aspirations of peoples to make life dignified and prosperous. The two unceasingly carry on war against dreams and initiatives to make life humane.

What has the assault on imperialism and colonialism achieved? Peoples, billions in number, in countries once colonised know the answer. First, they can plan their next journey – towards a society free from exploitation, towards a life with dignity. Now, they have a stand on the world stage, a voice once unheard and ignored. It’s broadly the same assertions, declarations, charters, and proclamations, including the United States Declaration of Independence and the English and United States Bills of Rights made: All women and men are equal, all men and women are endowed with certain unalienable rights that include life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It’s an achievement that lays a foundation for building up humanity’s eternal yearning: freedom, freedom from all exploitation, all distortions, all trampling, all muzzling down, all chains, and this freedom is a prerequisite for building up a life happy, peaceful, and prosperous.

The proletariat in Soviet Russia made a far more advanced declaration almost immediately after the Great October Revolution as it declared: Abolish all exploitation, completely eliminate the division of society into classes, mercilessly crush the resistance of the exploiters, establish a socialist organisation of society. [[i]]

The declaration, forgotten most of the time by the mainstream media, and even by a part of the pro-people political forces, is one of the most significant political achievements the exploited have so far made as it laid the legal foundation for rights of all the exploited, against all sorts of exploitation, and invalidated all claims of the exploiting classes. The revolutionary political document declared sovereign power of the working people. The historic document declared the abolishing of private ownership of all land, and parasitic sections of society; supremacy of the power of the working people over the exploiters; the complete conversion of all banks, factories, mines, railways, and other means of production and transport into the property of the workers’ and peasants’ state; complete break with the barbarous policy of bourgeois civilisation, which has built the prosperity of the exploiters; freedom of humanity from the clutches of finance capital and imperialism; and democratic peace between nations on the basis of free self-determination of nations. The Declaration is fundamentally different from all declarations of rights the bourgeois and feudal political systems, compromises between them issued until today.

It directly and unequivocally stood for the rights of the exploited. The declaration made assault on exploitative property relations, and declared measures for empowering the working people to resist the exploiting classes. [[ii]]

“Struggles against [the] class enemy” [of the exploited], writes Professor Michael Yates, “have resulted in tremendous and positive changes in the lives of the oppressed and expropriated.” He refers to the lives of nearly all workers during capitalism’s early days in Europe, to the condition of the peasantry in pre-1949 revolution in China. Improvements in these areas are monumental.

However, the economist does not miss the fact of life:

“And yet, workers and peasants are nowhere close to their full liberation”. This is the unfinished war of the working class.

It’s – the struggle of the exploited for emancipation – a long struggle. None can ignore this fact. A complete and permanent victory will follow long, innumerable struggles against capital and all its accomplices in lands across the globe, developments within struggles of the exploited and within the decaying force – the imperialist world order.

The chapter focuses on accomplishments “the working class has achieved in its struggle against exploitation, the first aspect of capitalist oppression.”

On “the second element of this subjugation, expropriation,” the chapter claims:

“[L]abour unions and political organisations have done some good. Most unions and political parties are committed to racial, ethnic, and gender equality. It is common for collective bargaining agreements to contain broad no-discrimination clauses. […] [T]he race, ethnic, and gender composition of union leadership mirrors the share of these groups in the larger population. [….] A few unions, notably those with majority women membership, have female presidents, and both women and minorities now have greater access to better-paying jobs than was once the case. The gap between the wages of women and men is lower in the rich European countries than in the United States, and this can be largely attributed to the demands coming from the labour movement and worker-centred political parties.”

However, as self-criticism, the chapter says boldly: “[T]he labour movement in the global North has done very little to oppose the theft of peasant lands in the global South.”

Absence of resistance to theft of the peasant lands in the global South is not the only area of failure of the labour in the global North. Along with the buying/leasing in of vast tracts of lands in Africa and the establishment of export processing/special economic zones by powerful capital in countries of the global South, powerful parts of world capital are exporting environmentally harmful technology, industrial waste and commodities, and medical products harmful to the health of the global South. The labour in the global North has also failed to organise effective resistance to this assault by capital. It’s part of labour’s unfinished war against the world capital.

These failures originate in (1) capital’s power to corrupt a section of labour leadership, and (2) labour’s lack of success in formulating a revolutionary theory on the related area. It’s an exhibit of the level of political awareness and struggle the labour is waging in the global North.

However, Michael Yates writes, “[i]n their own countries, the Northern labour has championed policies and programmes, as well as collective bargaining provisions, that make workplaces healthier spaces and countries less polluted.”

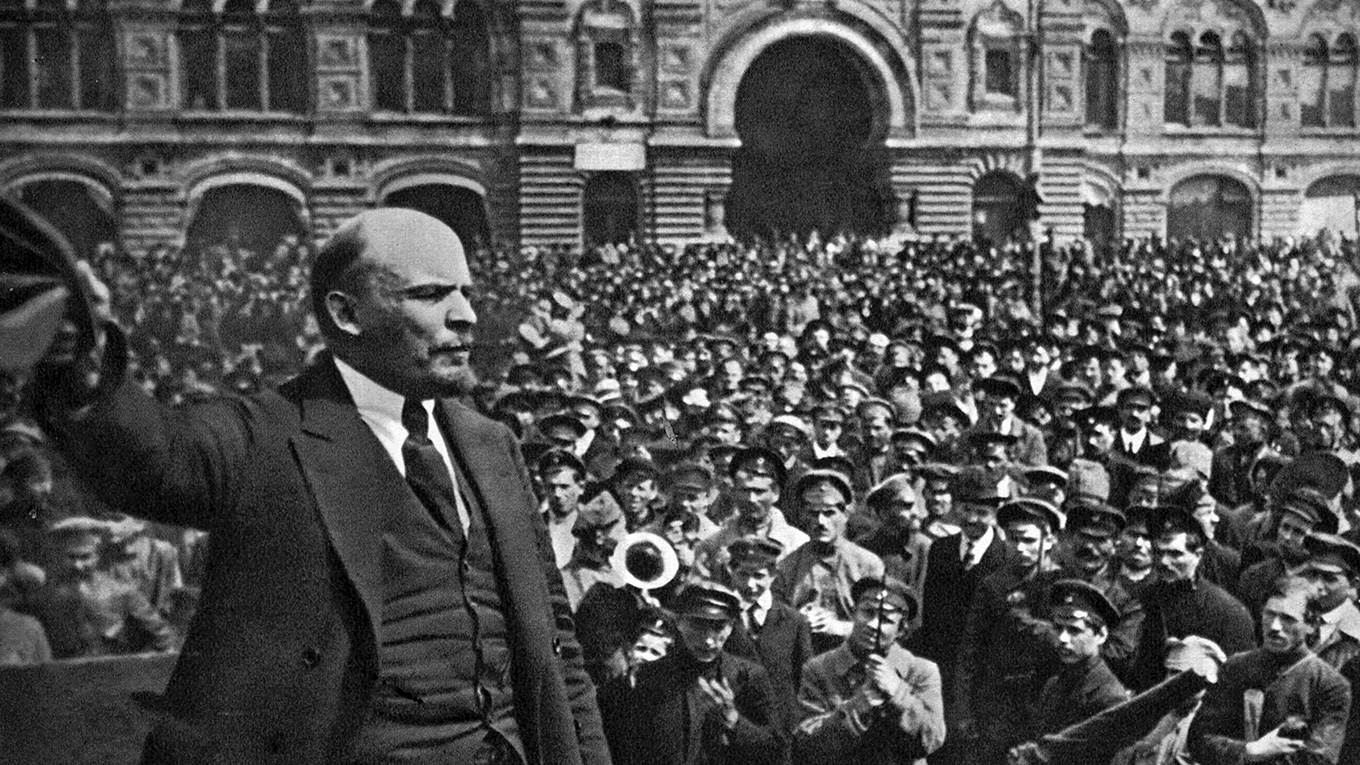

He mentions the Great October Revolution in Russia:

“The Revolution was successful, in that the Bolsheviks managed to consolidate state power. However, this was only after years of civil war, aided and abetted in the most brutal manner by the imperial powers, mainly Great Britain and the United States.”

Although the revolution, the economist writes, was not successful in consolidating the Soviet power and building a working class society, great gains were “made for the workers and peasants of Russia, and after the Second World War for the countries in the Soviet bloc. Guaranteed employment, excellent education and healthcare, run by the state and free of charge, subsidised rent and food, exceptional art, literature, music, and science, and a considerable erosion of patriarchy are some of the Revolution’s major achievements, not to mention its primary responsibility for the defeat of the Nazis in the Second World War.”

Regarding the question of the absence of success in some areas by the revolution in Russia, Lenin’s observation should be mentioned:

“[W]e have sustained the greatest number of reverses and have made most mistakes. How could anyone expect that a task so new to the world could be begun without reverses and without mistakes! [[iii]]

Michael Yates cites socialist revolutions in China, Vietnam, and Cuba as achievements of the working class. In China and Vietnam, Professor Michael Yates writes, “great improvements were made in schooling, health, and overall social welfare for the masses of people. Cuba’s Revolution has made tremendous advances in the lives of the people. Education, healthcare, organic farming, urban agriculture, and medical research in Cuba are world class. Progress against racism, patriarchy, and homophobia in the country is also remarkable.”

Cuba is spectacular in terms of time. Cuba is unprecedented in terms of political atmosphere. Cuba is exemplary in terms of the existing world order. Why? Anyone can ask. Russia and China are vast landmasses, are rich with huge natural resources. China had Soviet Russia on its back. Cuba had nothing of those. Cuba is still braving an imperialist economic blockade. Cuba is encountering a hostile world market. Moreover, Cuba is at a stone’s throw distance from the most powerful imperialist power. In addition to these, Cuba was standing alone during the time – the time of Gorbachev. It was a time of betrayal. It was a time of setbacks. It was a time of fallen “heroes.” It was a time when survival was a success. Cuba stood bravely. Cuba stood with the Red Flag. Cuba not only strode the current, but also made achievements with its political process – a form of democracy with people’s participation.

It’s striking performance by ordinary people with the Red Banner, the colour of the exploited. In the history of the world, no other class has survived and performed at this level within such a hostile world environment. And, Cuba is referenced not to belittle revolutions in Russia and China, but to highlight the sense of dignity, courage, tenacity and achievements of the working class.

The chapter of the book begins with a reference to a 2016-general strike by the workers in India: the largest such a strike in the world. About 180 million workers in every Indian state, in all sectors and in nearly every occupation, walked out. Tens of millions of women struck.

The chapter reminds with a modest tone: “Nothing remotely similar could take place in today’s United States, or in any rich capitalist country.”

This is a fact of working class life, which in many terms depends on capital, making the struggle, and gains and setbacks uneven, almost unpredictable. “And yet, from capitalism’s birth centuries ago, those harmed most by its imperatives have resisted. Their defeats have been many, their victories too few”, says Michael Yates in the chapter that takes an account of gains and losses. Hence, the labour educator says:

“[The working class through] their struggles have changed the world. Peasants have resisted with their own organised violence the expropriation of their farms and common lands. Wage workers, including those unemployed, have marched, picketed, boycotted, struck, sat-in, sabotaged, stole and destroyed their employers’ materials, and petitioned governments. They have contested capital’s power in every institution of their societies, from schools to media to religion. There have been times when both peasants and workers have engaged in armed battle with both capitalists and governments. In a few cases, alliances of workers and peasants made revolutions – in Russia, China, Cuba, Vietnam. Women were critical in all these alliances.”

No other class has struggled so much, has paid so much. And, all these struggles, all these payments – supreme sacrifices in innumerable numbers – were for the entire humanity, for freeing humanity from the clutches of capital, the most barbaric and brutal force human history has encountered. This is a major gain in this world, which demands a radical change.

Michael Yates writes: “Unions are a universal response of the working class to capital’s oppression. [….] Not only do they win higher wages [and] benefits […], unions also weaken the control employers have over hiring, promotion, layoffs, discipline, the introduction of machinery, the pace of work, and plant closings.” This is no less important gain for the working class.

Citing data, he discusses unionisation/union density and its positive impact in countries across the Americas, Europe, and in many countries in the global South. He says: “Three critical functions of labour unions are that they give workers a voice on the job, guarantee due process, and educate their members about a wide variety of important subjects.”

The labour economist, one of his many duties, recollects, “I have had personal experience as a labour arbitrator, and on more than one occasion I reinstated a fired employee, with full back pay, after determining that the company had wrongfully discharged him.” Hence, one of the gains by the working class: “Every year, unions win thousands of arbitrations”. On the global scale, in struggles against the world capital, the total number of arbitrations won is huge, which is not a negligible achievement by a class in chains.

One of the achievements of the working class is told in mainstream literature as it refers to an argument: “[A]t a crucial moment in history– the period between WWI and WWII and then in the early post-war years – in some countries, […] the labour movement and its political allies were able […] to force capital into a historical compromise, whereby labour accepted the capitalist organisation of the economy, but in exchange obtained not only a recognition of its prerogatives as labour market intermediary […], but also protection against all sorts of social risks, and a growing expansion of social rights.”[[iv]] This tells of an achievement and of an unfinished war.

For union organisers, the chapter presents, in brief, a good lesson, as it says:

“The formation of a union is a collective effort, and engaging in it, confronting the boss, is bound to make workers think about what they have done and what they hope to achieve. That is, labour unions are bound to raise the consciousness of those who form them. At the same time, labour organisers always try to educate prospective members, and the union itself provides educational materials and may even have developed more formal educational programmes for the rank and file. The best unions insist that new members learn the history of the union, the provisions of the relevant labour laws, the political platform of the union, and the details of bargaining and filing grievances. They might have special meetings, short courses, and longer schooling opportunities for the rank and file. Good unions also work hard to involve members in every facet of union work. Active participation in grievances, strikes, picketing, boycotting, and political agitation helps to further strengthen working-class consciousness, making workers stronger in their convictions and willing to live the precept that an injury to one is an injury to all. A working-class way of looking at the world begins to take shape, and this prepares workers for whatever struggles ensue during their lives.”

This is absent in many unions, especially in many countries dominated by lumpenocracy in the global South. In these economies, dominating capital engages hoodlums to organise/control unions. At the same time, a group of non-governmental organisations, on behalf of capital, organises “unions” – a trick with workers, and a bitter reality made possible by a vacuum of revolutionary working class politics and unionisation. In some cases, organisations with medieval ideology organise “unions” in countries. In other cases, a group of big unions from the global North organises “unions” in the countries of the global South with the purpose of taming the working class. In all these mal-efforts, huge money is spent, employees with a fat salary are engaged, and ludicrous foreign trips for these employees, the so-called “union organisers”, are organised. All these efforts forget the slogan of class struggle, shy away from imparting lesson of class politics. It’s an area, where the working class faces one of its unfinished wars.

Burning examples of working class initiatives are, among many, in the landless peasantry’s fights in Brazil, and in Shankar Guha Niyogi’s heroic struggles in India.

Niyogi, the martyr from the rank of the working class, initiated a struggle while adventurism was taking a high toll. Shankar Guha Niyogi was the founder of the Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha, a labour union in Chhattisgarh. After the formation of the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (CPI (M-L)) on 22 April 1969, he was associated with the CPI (M-L) for some time. However, CPI (M-L)’s failure to adapt Niyogi’s mass line-based activities to the party line of boycott of mass line and mass organisations led to his expulsion from the party. He went underground and began taking his ideas and method of work to the ordinary workers through a Hindi weekly, which he named Sphulinga (Spark), inspired by Lenin’s Iskra. He continued the work of organising the people through movements, e.g. movement for the construction of the Daihan dam, movement of the peasants of Balod for irrigation water, movement of the adivasis (indigenous people) against the construction of the Mongra dam.

Unions organised by Niyogi include Chhattisgarh Mines Shramik Sangh, whose red-green flag carried the message: red for workers’ self-sacrifice and green for the peasantry. The first struggle of miners under Niyogi’s leadership was a struggle for dignity: do not obey the agreement signed by the leaders, lackeys of factory management. Many struggles by the workers, police atrocities, martyrs, and victories by the workers are marks of struggles led by Niyogi. Unique forms of struggles, organising cultural activities, and establishing athletic clubs, schools and hospital – Shaheed (Martyr) Hospital – for the workers are signatures of his struggle and organisation. On 28 September 1991, assassins hired by class enemies – capitalists – murdered Niyogi, a comrade to follow.

One important section of the chapter is on labour politics. In this section, Michael Yates writes:

“[U]nions […] sooner or later they must confront government. The state, at every level, is intertwined with capital, labour’s primary adversary. [….] The largest and most powerful states have virtually unlimited taxing and spending power. Governments make and enforce laws; they have the only legitimate (in the sense of being formally legal) police power. The courts ultimately determine the meaning of the laws. Important components of government regulate a wide array of activities and groups of workers that might concern business […] The state has the power to regulate and influence financial markets […] States wage wars. No matter what the government does, capital exerts its economic power to limit tax liabilities and receive as much public spending as possible, to influence the selection of judges, or to counter anything that challenges its social power. Given all of this, unions have little choice but to be politically engaged.”

The chapter cites an example: “Unions have embraced a range of political programmes and philosophies.” It presents a brief history of the labour politics in the US. At the same time, it says: “Around the world, some working-class entities opposed active involvement in what we might call bourgeois politics.”

Instead of being engaged with bourgeois politics, the working class is to get engaged with politics of its class that crosses all divisive lines of colour, caste, and creed, if the class has to complete its unfinished war, a commitment to the humanity.

Struggles, achievements, and the unfinished war of the working class declare its position, as Lenin said:

“We have made the start. When, at what date and time, and the proletarians of which nation will complete this process is not important. The important thing is that the ice has been broken; the road is open, the way has been shown. [….]

“[W]e have begun it. We shall continue it. […]

“We shall go through the whole ‘course’, although the present state of world economics and world politics has made that course much longer and much more difficult than we would have liked. No matter at what cost, no matter how severe the hardships of the transition period may be – despite disaster, famine, and ruin – we shall not flinch; we shall triumphantly carry our cause to its goal. (op. cit.)

* Farooque Chowdhury writes from Dhaka, Bangladesh.

* Note: This is part five of a seven-part series review of Can the Working Class Change the World?.

[i]“Declaration of Rights of the Working and Exploited People”, V I Lenin, Collected Works, vol. 26, Progress Publishers, Moscow, erstwhile USSR, 1972

[ii]Farooque Chowdhury, “The Great October Revolution: Declaration of Rights of the Working and Exploited People”, Countercurrents.org

[iii]“Fourth anniversary of the October Revolution”, Collected Works, vol. 33, Progress Publishers, 1976

[iv]Lucio Baccaro, “Labor, Globalization and Inequality: Are Trade Unions Still Redistributive?”, International Institute for Labor Studies, ILO, discussion paper, DP/192/2008, Geneva, 2008