Pan-Afrikanism/Black Consciousness and decolonisation of ‘higher learning’

Decolonisation of the Afrikan university must be located within the over 1,000-year-old struggle of Black people all over the world against white supremacy. It must aim at organising Black people towards the attainment of a far higher ideal, perhaps best articulated by Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe who said: “We must fight for freedom. For the right to call our souls our own. And we must pay the price!”

1. Introductory remarks

Siyacamagusha Mafrika!

Let me start by expressing my sincerest appreciation to the leadership of the Pan Afrikanist Student Movement of Azania (PASMA) for the invitation to come and address this epoch-making gathering. I must also commend PASMA for their revolutionary maturity and foresight to, in constructing the discussion themes for today, present Pan-Afrikanism and Black Consciousness as branches of the same Afrocentric.

The unifying manner in which you have crafted the discussion themes is instructive because it symbolically reinforces one of the cardinal pillars of Pan Afrikanism / Black Consciousness, which is the unity of Black people. This is an important message because there continues to be a wind of pettiness that seeks to sow discord between the principal Pan Afrikanist and Black Consciousness- oriented movements that exist in the white-criminal-settler colony referred to as South Africa.

I greet you in the spirit of our nameless ancestors, whose bodies were violently snatched from Afrika and scattered of all over the world like worthless grain. Camagu!

They whose bodies were thrown off the slave ships and fed to the sharks that have learned to trail these ships. Camagu!

They whose bodies were bent beyond their limit, wrapped around trees and had their flesh ripped apart by the whips of their slave masters. Camagu!

I greet you in the name of 19-year-old Mary Turner of Brooks County, Georgia, who in May 1918, was captured by a white mob, tied and hung upside down by the ankles. Her clothes were soaked with gasoline, and then her body was set alight. Her body was slit open with a knife and when her unborn baby fell out, the baby’s head was crushed by a member of the mob and the crowd shot hundreds of bullets into her mutilated body. Mary was 8 months pregnant and was lynched for simply pleading her husband’s innocence, who was falsely accused of killing his white slave master. Camagu!

I greet you in the name of 22-year-old Amadou Diallo of Guinea, who in February 1999, was confronted by four white cops on the doorstep of his apartment in New York. Before he could make sense of all that was happening, he was shot and killed. The cops fired a combined total of 41 shots, 19 of which struck him. They claimed it was a case of mistaken identity as they had mistaken him for a wanted rapist and that when he reached for his wallet, they thought he was reaching for his gun. No gun was found at the murder scene. Only his wallet and beeper. Camagu!

I greet you in the name of 16-year-old Mathlomola Mosweu who was brutally murdered earlier this year on a farm in Coligny, in the North West. He was killed for allegedly stealing sunflower. Describing the condition of his son’s body when he saw it after hearing the terrible news, his father, Ntate Sakkie Dingake, said: “His neck [was] broken, the head moved loosely from one side to another. He had a cut on his throat, on the chin and at the back of his neck. There was also blood in his mouth." Camagu!

I also greet you in the names of the Warrior Queen, Mama Assata Olugbala Shakur, the Warrior Mumia Abu Jamal and the gladiators of APLA, all of whom remain caged. Camagu!

I have been requested to speak on the theme ‘Pan Afrikanism/Black Consciousness within the Context of the Call for Decolonisation in Institutions of Higher Learning’. The approach we propose is to focus on the history of Black radical resistance as represented by Black territorial and slave rebellions of the 7th to 15th century, and present these as practical manifestations of Pan Afrikanism/ Black Consciousness that should be used to give substance and impetus to the project of decolonisation today.

A closer look at the theme provokes a number of supplementary questions, some of which are:

- What do we understand by the concepts of Pan Afrikanism and Black Consciousness?

- What do we mean by decolonisation?

- What exactly do we mean by ‘institutions of higher learning’ ?; and

- For the psychic health of Black students, can we really talk of ‘higher learning’ or even ‘learning’, in the context of anti-Black universities?

I don’t promise to directly answer these supplementary questions and propose to address the theme I have given by looking at the following:

- Critical moments of Black radical resistance that occurred in the month of September;

- The evolution of radical Black resistance in the form of Black territorial and slave rebellions;

- The lessons we can learn from Black territorial and slave rebellions;

- The issues that Pan Afrikanist/ Black Consciousness movements must respond to in the context of today’s South Africa;

- The issues that Pan Afrikanist / Black Consciousness movements must respond to in the context of today’s Afrika; and

- The issues that Pan Afrikanist / Black Consciousness movements must respond to in the context of the world we live in.

2. Critical moments of Black radical resistance that occurred in september

In the month of September we remember a number of critical moments in the evolution of radical Black resistance. We mark the 188th anniversary of the publication of David Walkers’s epoch making anti-slavery essay titled ‘Appeal for a Slave Revolt’ on 28 September, 1829.

We mark the 179th anniversary of anti-slavery leader Frederick Douglass’s escape from slavery on 3 September, 1838.

We mark the 189th anniversary of the mysterious of death of one of the great warrior kings of our race, UNodumehlezi kaMenzi, UShaka akashayeki kanjengamanzi, Ilemb’ eleq’amanye amalembe ngokukhalipha, INkosi eNkulu uShaka kaSenzangakhona kaJama , on 22 September, 1828.

We mark the 93rd anniversary of the birth of one of Afrika’s finest revolutionaries, Amilcar Lopes da Costa Cabral, on 12 September, 1924.

We mark the 108th anniversary of the birth of one of the great Pan Afrikanist theoreticians of our time, Kwame Nkrumah, on 21 September, 1909.

We mark the 76th anniversary of the birth of a Black Power warrior of the highest calibre, George Lester Jackson, on 23 September in 1941.

We mark the 30th anniversary of the assassination of one of the most uncompromising warriors of our race, Peter Tosh, who was killed on 11 September, 1987.

We mark the 56th anniversary since the founding of the forerunner to the Azanian People’s Liberation Army (APLA), Poqo, which was formed on 11 September, 1961.

Then, of course, we also remember the 40th anniversary of the assassination of uMgcina omuhle, uBantu Biko, whose frame gave in around about the 12 September, 1977.

3. Territorial liberation wars and slave rebellions

From the 7th to 15th century, the principal oppressors of Black people were the pale-skinned Arabs and the Europeans. In reaction to the invasion of the Arabs and Europeans, successive generations of Black people waged gallant rebellions. These rebellions happened in Afrika, on the slave routes to what is strangely referred to as the Middle East, on the slave ships and on the various slave plantations, across the world. These rebellions also produced a number of iconic Warriors for the Black race.

In Mexico, there was Gasper Yanga, known as the “first liberator of the Americas.” Yanga was a Black slave who spent four decades establishing a free settlement in Mexico. He staged a revolt at a sugarcane plantation near Veracruz in 1570. After fleeing into the forest, Yanga and a small group of former slaves established their own colony, which they called San Lorenzo de los Negros. They would spend the next 40 years hiding in this community, surviving mostly through farming and occasional raids on Spanish supply convoys.

In Brazil, there was Zumbi Dos Palmeros, one of the principal leaders of the Black Brazilian slaves. Zumbi was a descendent of the Imbangala warriors of Angola and leader of one of the Quilombos. These were settlements formed by runaway slaves. He launched a number of slave rebellions. On 20 November 1695, Zumbi was captured and beheaded by the Portuguese, who displayed his head publicly as a way of instilling fear in other slaves. In honour of Zumbi, today, the 20 November is commemorated as National Black Consciousness Day in Brazil.

In Jamaica, there was Queen Nanny, a fearless leader of the Jamaican Maroons in the 18th century. After escaping from the plantation, Nanny and her brothers hid in the Blue Mountains area. From there, they led several revolts across Jamaica. Queen Nanny was a well-respected, intelligent spiritual leader who was instrumental in organising the plans to free enslaved Blacks. For over 30 years she freed more than 800 slaves and helped them settle into Maroon communities. She defeated the British in many battles and despite repeated attacks from the British soldiers, Grandy Nanny’s settlement, called Nanny Town, remained under Maroon control for several years.

In Haiti, you had Dutty Boukman, Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines who led what is arguably the most successful Black slave rebellion in history. This rebellion began as a slave revolt and ended with the founding of the first independent Black state, Haiti, in 1804.

The main insurrection started in 1791 in the French colony of Saint-Domingue. In 1804 after defeating French forces at the Battle of Vertières, the slaves declared their independence and established the island as the new republic of Haiti. The Haitian Revolution went on to inspire countless other revolts throughout the United States of AmeriKKKa and the Caribbean.

In the United States of AmeriKKKa, you had Nat Turner, who inspired one of the most famous slave revolts in AmeriKKKan history in 1831. Turner and his army killed his master’s family as they lay sleeping. From there, the small band of about 70 slaves moved from house to house, eventually killing over 50 whites with clubs, knives and muskets. It took a militia force to put down the rebellion, and Turner and 55 other slaves were captured and later executed by the state.

Turner’s rebellion resulted in more harsh measures being imposed on Black slaves. The slave masters made an observation that Turner’s intelligence was the key factor in the rebellion and so several states passed laws that made it illegal to teach Blacks to read or write.

In the Pacific, you had Tarenorerer of Emu Bay in northern Tasmania. She was an indigenous Australian leader of the Tommeginne people. In 1828, Tarenorerer gathered a group of men and women to initiate warfare against the invading Europeans. She trained her warriors in the use of firearms and ordered them to strike the luta tawin (white men) when they were at their most vulnerable, between the time that their guns were discharged and before they were able to reload. She also instructed them to kill the Europeans’ sheep and bullocks.

3.1 Afrika

At the same that Black people in other parts of the world where engaged in anti-white supremacist rebellions, Black people on the Afrikan continent were also unleashing their own wave of rebellions against all manner of invaders. This was the case because Black people in Afrika and in other parts of the world were wrestling with the same beast- the historically-evolved-globalised system of white supremacy, which has its genesis in the institution of slavery.

In what is now called Angola, you had Queen Nzinga Mbande of the Ndongo and Matamba Kingdoms. Nzinga fearlessly and cleverly fought against the Portuguese. At the time of Nzinga’s death in 1661 at the age of 81, Matamba had become a powerful kingdom that managed to resist Portuguese invasion attempts for an extended period of time.

In 1896, Black people secured a decisive victory over Italian invasion in the Battle of Adwa, under the leadership of Emperor Menelik. This tradition of gallant resistance continued in the 20th century. You had the Warrior QUEEN YAA ASANTEWAA, Queen mother of the Edweso community of the Ashanti people of Ghana. An exceptionally brave warrior who led an army of thousands against British invasion, Yaa Asantewaa’s War, as it is presently known in Ghana, was one of the last major rebellion wars on the continent of Afrika to be led by a woman.

In the mid-20th century, you had the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya, under the leadership of amongst others Dedan Kimathi from the period 1952 to 1960. The Mau Mau rebellion was a response to European invasion, land theft and gave impetus to the liberation struggle in Kenya and Afrika.

In the southern tip, from 1659 to about 1803, there was a series of resistance wars that were led by the Khoi, under freedom fighters such as Die Strandloopers, the Goringhaiqua under Gogosa and Doman. One of the outstanding warriors of this period is Aaa! UNzalakaMatoti, kaMfebe, kaPulu, kaDladla, KaMachapaza, kaTshangisa, kaSnuka, kaSkhomo, kaRhudulu! Ahhh Zululiyangoma! AaahMgwevu! The legendary Inkosi uDavid Stuurman, who escaped more than once from the colonial dungeon now known as Robben Island.

We would also recall how in 1879 Black people trounced the British in the Battle of Isandlwana, during the time of Inkosi uCetshwayo. One of the commanders during Isandlawana is my great ancestor, uMavumengwana kaNdlela Ntuli.

Then at the beginning of the 20th century, you had the Herero and Nama uprising in what is now known as Nambia, in 1904, under the leadership of Samuel Maharero. They decided to rise up against the German invaders, killed about a 123 of them and set buildings alight. In reaction, the Germans launched a bloody and brutal war of extermination against the Herero and the Nama. This extermination is considered by some as the first genocide of the 20th century.

Then you also had the rebellion led by Inkosi uBhambatha kaMancinza Zondi in 1906. This rebellion is usually reduced to a revolt against a British-imposed tax, but like all the resistance wars that were fought in Afrika, the Bambatha rebellion was actually a revolt against European invasion.

4. What lessons can we learn from these Black territorial and slave rebellions?

There are number of lessons that these rebellions teach us. One, for the longest time, Black people (everywhere in the world), have existed in a context of slavery. Two, in spite of the vicious and brutal nature of the violence that was periodically unleashed on the bodies of Black people, throughout the various epochs of slavery, there were always groups of Black people who were prepared to risk their lives and rise up against their enslavers.

Three, these rebellions also inform us that, at various times, Black women played a leading role in the resistance against the enslavers of Black people.

Four, the existential reality of Black people is not comparable or identical to that of any other racial group on earth.

Five, regardless of where they were (or are) in the world, all Black people were pitted against the same-all-consuming-obliterating-violence-driven beast: white supremacy.

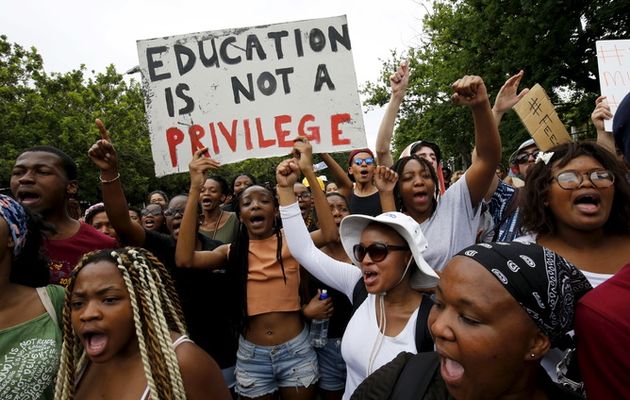

Six, if we accept the Black experience as interconnected, trans-generational and trans-continental, then it is sensible to view our contemporary resistance history in South Africa, as represented by the amongst others, the Sharpeville uprising of 1960, the Soweto student uprising of 1976, the Marikana uprising of 2012 and, of course, the Must Fall uprising, as nothing else but the Black slave rebellions of our time.

Seven, because Black people everywhere have and continue to exist in a context of slavery, the call for decolonisation by Black students today should be seen as a continuation of the Black slave rebellions of the past 1,000 years or so- against the various enslavers of Black people. To help us understand the intricacies of this connection between our past and contemporary contexts, in his book, Blood in My Eye, George Jackson makes the point that: “the terms of our servitude are all that has been altered’.

Furthermore, the call for decolonisation today only qualifies to be a continuation of the sacred mission of our warrior ancestors if by decolonisation the Black students of today mean a conscious, organised and violent rebellion by Black people (everywhere in the world), which seeks to obliterate the historically-evolved-global anatomy and physiology of the white supremacist order, in all its manifestations and, thereafter, usher in a world order wherein Black people are able to be human beings of their own creation, who live by their own value system.

We make this point for at least three reasons. First, the system of white supremacy is not just automatically and mechanically anti-Black; it is also automatically and mechanically violent. So the only language that white supremacy speaks and hears is violence. Secondly, decolonisation (as I have described it) shouldn’t be reduced to a project that confines itself to fighting for changes in the language policies of universities, the appointment of more Black or female deans, lecturers or vice chancellors or calls for these Yurugu universities to be renamed after Black freedom fighters. The call for decolonisation by Black students must be based on something much more fundamental than the peculiarities of white supremacy in universities.

5. What are the issues that Pan Afrikanist/ Black Consciousness movements must respond to in the context of today’s south africa?

In the context of South Afrika today, Pan Afrikanist/Black Consciousness movements must confront the following:

- The brutalisation and killing of Black women by us Black men. There can no Black Liberation or Black Power in an atmosphere where Black women fear that they might be brutalised or killed by Black men. Black women and Black men are supposed to form a unified force against the enemies of Black people;

- To call for justice for those Black people who were killed by the police such as Nqobile Nzuza, Andries Tatane, Jan Rivombo, Mike Tshele, Osiah Rahube, Lerato Seema, the Black workers of Marikana and others who died mysteriously like Sikhosiphi Rhadebe;

- The incidents of Black people being publicly attacked or killed by European invaders such as in the cases of the Sono family who were brutally attacked at KFC in Tshwane or that of the 9-year-old Black girl from Zithobeni, near Bronkhorstspruit, who was tied to a tree and assaulted by two white men, until she urinated on herself;

- The monumental contradiction wherein anti-Black groups like Afri-Forum can legally and openly defend white supremacy, but Blacks get charged with ‘hate speech’ for legitimately fighting against white supremacy;

- The fragmented efforts towards Black liberation and the absence of a well-thought and unifying Black revolutionary agenda today; and

- The persistence of Black landlessness and all other manifestations of Black powerlessness.

6. What are the issues that Pan Afrikanist/ Black Consciousness movements must respond to in the context of today’s Afrika?

In the context of today’s Afrika, Pan Afrikanist/ Black Consciousness movements must confront the following:

- The neo-colonial violence wherein, even after declaring independence, countries such as Benin, Burkina Faso, Guinea Bissau, Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo-Brazzaville, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon, are forced by France, through an imperialist policy called Francafrique to store their national reserves in the French central bank. These Afrikan countries are essentially paying France for colonising them;

- The treachery of some Afrikan leaders who conspire with the Arab, European and Asian plutocrats to facilitate the looting of the natural wealth of Afrika and fomenting proxy imperialist wars, especially in South Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Uganda and Burundi;

- The new scramble for Afrika as represented by Chinese imperialism;

- The treacherous silence of Afrika’s leaders, and in particular the African Union, on the continued brutalisation, capture and killing of Afrikans in places such as Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, the so-called Arab world and Israel; and

- Most disturbingly, the paradox where today’s Afrikan head of state would issue strong statements condemning the so-called terror attacks in France and Belgian, etc, but would say nothing about the atrocities committed by the Ugandan government in Kasese or those by the Ethiopian government against the Anuak or the continued drowning of Afrikans in the Meditareanen.

Shouldn’t these be the issues that dominate the agenda of bodies like the African Union?

7. What are the issues that Pan-Afrikanist/ Black Consciousness movements must respond to in the context of the world?

In addition to the responding to the issues of Black people in Afrika, the global Pan Africanist / Black Consciousness movement must also respond to the following:

- The failure of today’s Black leaders, who go to the United Nations and other multilateral platforms, to protest against the ill-treatment of the Palestinians, the Syrians and now Rohingya in Myanmar, but don’t raise a finger in protest against the genocide of our Black kin in West Papua.

- The failure of Black leaders to confront and hold the Unites States of AmeriKKKa accountable for the continued lynching of Black people by the state in the form of Tamir Rice, Henry Green, John Crawford, Sandra Bland, Sam Dubose, Tanisha Andersen, Mike Brown, Laquan McDonald, Freddie Gray, Bettie Jones, and recently, Philando Castille; and

- The implications of the absence of a global and revolutionary political body that concerns itself with the issues that face Black, across the world.

8. Concluding observations

In conclusion, a revolutionary Pan Africanist/ Black Consciousness student movement like PASMA must avoid the ideological trap of confusing the decolonisation project with the nyaopish project that calls for the ‘transformation of higher education’. Decolonisation for PASMA should mean to locate the struggles of Black students on university campuses within the bosom of the over 1,000-year-old fight of Black people all over the world against white supremacy and anti-Blackness.

And given the over 1,000 years tradition of Black radical resistance, it becomes clear, at least to me, that the call for decolonised education or universities, while important from the perspective of raising the required revolutionary consciousness, shouldn’t be viewed as being the ultimate embodiment of the essence of our fight as Black people.

It should rather be viewed as a platform of struggle from which to organise and mobilise Black towards the attainment of a much higher ideal. This higher ideal is perhaps best articulated by uBaw’uHlathi, uMangaliso Sobukwe, who at age 25 said:

“...We must fight for freedom. For the right to call our souls our own. And we must pay the price.”

In the context of our time, Sobukwe seems to be saying to us: a decolonised education or university will be meaningless in a context wherein the indigenous Black majority remains landless, country-less, leaderless, fragmented or when our souls are not our own.

Most fundamentally, he seems to be saying to us: to be able to reclaim our souls (or achieve complete decolonisation), we must be prepared to, amongst others, engage in a physical confrontation with those who deny us the right to call our souls our own. Therefore, in my view, to call for decolonisation today is to call for a violent rebellion by Black people in Afrika and other parts of the world, against the brutal-merciless-violent and global white supremacist order.

Sithokoze! Camagu!

* VELI MBELE is an essayist and Black Power activist.

Selected references

http://atlantablackstar.com/2013/10/29/10-fearless-black-female-warriors-throughout-history/

http://www.blackpast.org/perspectives/battle-adwa-adowa-1896

http://www.sahistory.org.za/article/herero-revolt-1904-1907

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h2931t.html

http://www.history.com/news/history-lists/7-famous-slave-revolts

http://abolition.e2bn.org/resistance_63.html

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to [email=[email protected]]editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org[/email] or comment online at Pambazuka News.