Does Lonmin’s inclement death resolve – or reload – the Marikana massacre?

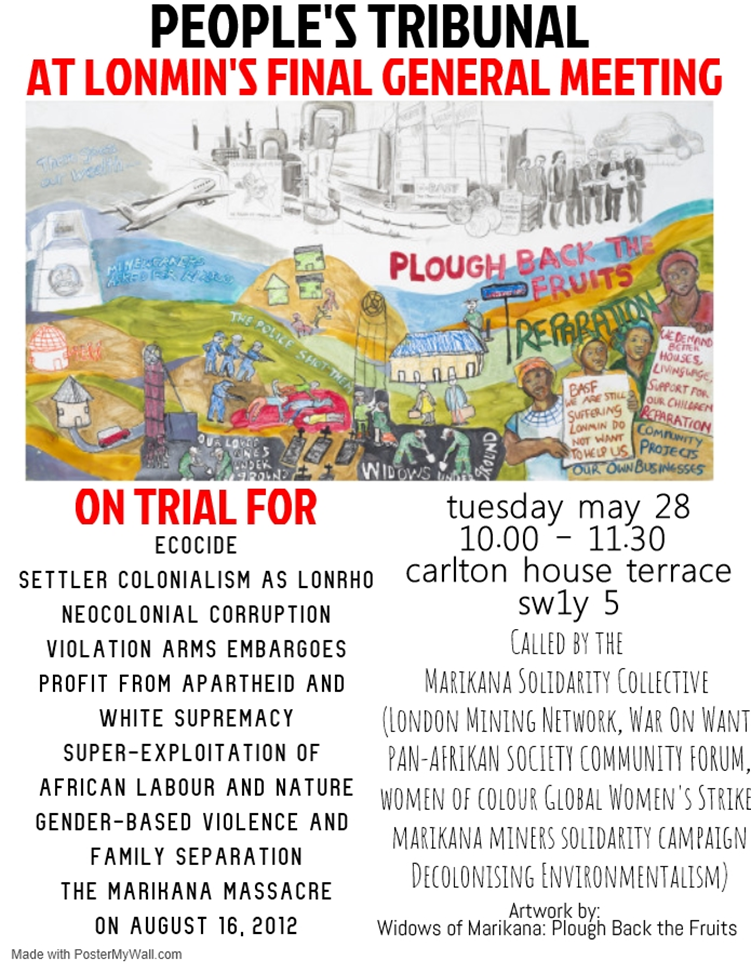

In a few days, the world’s third largest platinimum mining house, Lonmin, will likely be remembered as the exemplar of multinational corporate irresponsibility. As a people’s trial hosted by the Marikana Solidarity Network gets underway outside Carlton House Terrace in London, where Lonmin’s shareholders vote on a friendly takeover deal (albeit with extremely dubious characteristics), many critics are shaking their heads – and fists – at the extraordinary financial and political circumstances.

Starting in 1909, the London and Rhodesian Mining and Land Company was a backwater mining house until it became one of the world’s most predatory corporations. The critical shift was Lonrho’s growth away from its origins in what is now Harare, during the 1962-93 leadership of Roland Walter Fuhrhop, a German who renamed himself Tiny Rowland and emigrated to England and then Rhodesia.

By the early 1970s, an unprecedented internal rebellion of directors against its flamboyant leader led to court proceedings that revealed much about Lonrho’s modus operandi. As Brian Cloughly explained,

“A British prime minister, Edward Heath, observed in 1973 that a businessman, a truly horrible savage called ‘Tiny’ Rowland, represented “the unpleasant and unacceptable face of capitalism.” The description was fitting because Rowland was a perambulating piece of filth who had indulged in bribery, tax-dodging, and the general range of ingenious whizz-kid schemes designed to make viciously unscrupulous people rich and keep them that way.”

The majority of that wealth was stripped from Southern Africa, especially an area two hours drive from Johannesburg, in Rustenburg’s Western Platinum mines. By the early 1970s, they had become the most consistent source of Rowland’s profits, in some years exceeding half the firm’s earnings. But by 2017 it became obvious that Lonmin’s on-going bribery of political leaders (especially in Africa), and its attacks on labour, community (especially women) and the environment were self-destructive on two grounds:

- a legacy of hatred that spilled over into the political sphere, reaching to the very top of South African politics, and

- an exceptional devaluation of investor worth, for what had become the world’s third largest platinum corporation – after Implats and Anglo American – was suddenly (and to many, mercifully) swallowed by a young (five year old) Johannesburg-based mining house, SibanyeStillwater.

The price for all of Lonmin’s London Stock Exchange shares offered in December 2017 was a measly US$383 million, which was at the time just a seventh of Sibanye’s share value at the time, and a tiny fraction (1.4 percent) of Lonmin’s US$28.6 billion peak value a decade earlier.

But its owners were glad to accept even these few crumbs, and indeed the final package of Sibanye trade-in shares was increased in April 2019 as platinum prices rose 11 percent in the four prior months, shortly before shareholder approval would finalise the deal.

Yet as journalist Felix Njini pointed out at the time, “While Sibanye has boosted the share ratio it is offering to Lonmin investors, the value of the deal remains lower than when it was announced, after the company’s share price fell and it sold new equity earlier in April.”

During the 2007-17 crash, Lonmin, its management, and especially its main South African investor (and protector) Cyril Ramaphosa, together deserved their neo-Rowlandian reputations. They sought profits at any cost, even the irreparable soiling of their own nests.

To be sure, last Saturday [25 May 2019] Ramaphosa was sworn in as South Africa’s president, after his party won the 8 May election with a much reduced 58 percent of the national vote – gaining a tick from only 30 percent of those who were eligible as apathy and disgust reduced voter participation to an unprecedented [low] level.

That tradition of profits-at-any-cost will continue in coming years under Sibanye’s notorious Chief Executive Officer Neil Froneman. Even in the crucial 2012-19 years when reform should have been possible, there continued to be excruciating attacks on Lonmin’s workers, the Marikana community and the surrounding ecological systems, of which the worst single incident was at the platinum mine two hours’ drive northwest of Johannesburg.

On 15 August 2012 Ramaphosa emailed a request to the police minister regarding a week-long wildcat strike at a Marikana mine of which he owned more than 9 percent: “The terrible events that have unfolded cannot be described as a labour dispute. They are plainly dastardly criminal and must be characterised as such … there needs to be concomitant action to address this situation.”

Ramaphosa was referring to 4000 desperately underpaid miners, and the violence they had suffered and meted out the prior week, during which six workers, two security guards and two policemen died in skirmishes. Neither Lonmin officials nor its board’s Transformation Committee leader Ramaphosa wanted to negotiate.

The main union then representing the platinum workers, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM, which was courageously led by Ramaphosa during the 1980s), sided with the management. The day after his emails, strikers began to peacefully depart the hillside where they gathered for the nearby shantytowns, heading home for the weekend. They were blocked by barbed wire hastily assembled by police, and then 34 of the workers were shot dead, and 78 wounded.

The police acted not dissimilarly to those of the pre-1994 apartheid era, with a visceral hatred of the rebellious workers; class had simply replaced race in the calculus (since the police shooters were largely black, including most of their commanders). Ramaphosa’s role was especially unconscionable given his struggle history.

In the 2014 Emmy Award-winning film Miners Shot Down, director Rehad Desai reveals the class-loyalty U-turn. In 1987 in the midst of a legendary strike, Ramaphosa accused the “liberal bourgeoisie” of using “fascistic” methods. Thirty years later Ramaphosa had become the main local investor in Lonmin, and within five years was a “monster,” according to local activists. He played a familiar role described by the workers’ lawyer, Dali Mpofu:

“At the heart of this was the toxic collusion between the SA Police Services and Lonmin at a direct level. At a much broader level it can be called a collusion between the State and capital… in the sordid history of the mining industry in this country. Part of that history included the collaboration of so-called tribal chiefs who were corrupt and were used by those oppressive governments to turn the self-sufficient black African farmers into slave labour workers. Today we have a situation where those chiefs have been replaced by so-called Black Economic Empowerment partners of these mines and carrying on that torch of collusion.”

Collusion resisted but not defeated

The post-massacre period provides many lessons about how Lonmin maintained its predatory approach and also how resistance was stymied, notwithstanding a crescendo of labour unrest culminating in a five-month strike across the platinum belt in 2014. Summing up the overall lack of improvement at Marikana three years after the massacre, photojournalist Greg Marinovich explained,

“The miners’ salaries have, over the course of two long and deadly strikes, been substantially increased. And their lives have improved, albeit not to the level that Lonmin promised back in 2007, when Brad Mills told Business Day the money would create ‘thriving’ and ‘comfortably middle class’ communities around Lonmin’s projects. Given the horror of the massacre at Marikana, it is not surprising that the failure of the state, municipalities and Lonmin to provide dignified and reasonable living conditions has been sidelined. But it is this squalid environment and the cynical disregard by those with the power to change it that provoked the miners to risk death in the first place. And for the women here, who are mostly shut out of formal employment possibilities, life remains an unremitting grind, despite the World Bank’s tagline: ‘Working for a World Free of Poverty.’”

Indeed although the Marikana Massacre’s impact on Ramaphosa, Lonmin and its victims was devastating, that incident alone did not immediately destroy the firm (for example, in the way the London public relations firm Bell Pottinger was quickly dismembered due to its South African mistakes in mid-2017).

Instead, the underlying dilemma that ultimately led to Lonmin’s death was the over-accumulation of minerals capital on the world scale, and the inability of Lonmin to keep its cost structure sufficiently low to avoid a takeover.

Froneman made clear that his main rationale in buying Lonmin was to consolidate the firm’s relatively cheaper smelting capacity at Marikana for use by other firms (although the return of electricity brownouts in 2018 and fast-rising tariffs quickly diluted this benefit). Closure of Lonmin mineshafts will accelerate, and the Social and Labour Plans will continue to be ignored.

Already in 2016, Lonmin’s workforce shrunk dramatically, from 40 000 to 33 000 employees, with another 8000 workers fired in 2018 and 4100 in mid-2019. Sibanye’s takeover plan projected the firing of a further 12 600 Lonmin workers within three years.

A subsequent price recovery of one metal, palladium (closely related to platinum, rising from US$826/ounce in September 2018 to a March 2019 high of US$1601/ounce), apparently slowed Lonmin’s retrenchment process, but Sibanye remained intent on Lonmin labour rationalisation.

In general, Froneman’s treatment of workers was seen as exceptionally careless even in a South African context, with 24 mining fatalities at Sibanye in 2018 alone. That year Froneman was awarded salary and benefits worth US$3.8 million, even though the entire firm’s profits (before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation) were only US$47 million.

But the troubles Froneman brought upon himself at Sibanye were prefigured by the Marikana Massacre. The labour movement witnessed an extraordinary upsurge of shop-floor militancy in the subsequent weeks, and the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu) emerged so strong from the NUM’s demise at Lonmin, that it waged a five-month strike across the platinum belt in 2014.

In the wake of the massacre, Lonmin was also the site of new frictions with two new advocacy groups from the surrounding community: Bapo Ba Mogale and the Mining Forum of South Africa. The two groups complained,

“Lonmin has circumvented compliance wilfully and purposefully, a practice they have mastered for years with intent to secure interests of capital at the expense of the disadvantaged and the poor. They have a proven track record of presiding and surviving on hopelessness, volatility, death, instability, poverty and violence.”

The Massacre also humiliated a high-profile Lonmin financial supporter, the World Bank. The Bank’s 2007-12 celebration of Lonmin’s so-called “Strategic Community Investment” at Marikana attracted persistent complaints from a women’s community group, Sikhala Sonke (“We cry together”), supported by the Wits University Centre for Applied Legal Studies (CALS).

Another unnecessary casualty of Marikana was the possibility of an ambitious state-led mining policy, since who could trust a state led first by Jacob Zuma and then Ramaphosa, to safeguard workers, communities, women and environments. The then African National Congress (ANC) Youth League leader Julius Malema raised the demand for mining nationalisation at a 2011 conference, and as a result, a party disciplinary committee led by Ramaphosa expelled him and his comrades.

Malema subsequently founded the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) party and won a growing share of the platinum belt’s support in subsequent elections, rising to a third of the voters residing in Marikana’s shacks and hostels in the 2019 election (one of the EFF members of parliament was a feisty Sikhala Sonke founder, Primrose Sonti). The massacre had shifted South African politics forever.

The state’s response was to distract and defer from the deepest problems unveiled by the massacre. Wrongdoing was investigated by the 2012-15 Farlam Commission set up by Zuma, but the outcome was widely condemned as inadequate. It is tempting to emphasise the negligence or malevolence of personalities:

- Judge Ian Farlam blamed maniacal police leadership.

- Lonmin chief executive Ian Farmer’s salary was 236 times higher than the typical rock drill operator.

- Farmer’s main executive replacement Barnard Mokwena was later unveiled as a State Security Agency operative.

In the structure-agency dialectic, it is these kinds of characters who make it easy to villainise Lonmin and the state. But even when structural forces are at work, central personalities can be targeted for blame.

Thus while Lonmin was intent on Illicit Financial Flows, it was due to Ramaphosa’s strong support as leader of the Incwala black empowerment partner firm. According to Lonmin’s lawyer, “Incwala for very many years refused to agree” to changing what became a US$100 million outflow to the Bermuda tax haven justified as marketing expenses, even after Lonmin itself decided to end the tax-dodge.

The state did nothing to punish this; nor did it provide the reparations to massacred and injured mineworkers’ families that even Farlam recommended were due, for many years.

Perhaps the most blatant case of state-corporate collusion appeared in April 2019, when Amcu was threatened with deregistration by the South African Department of Labour, on grounds that it had not properly followed institutional procedures (such as regular conventions) that qualify it to be considered a trade union.

Sibanye’s Froneman had just humbled Amcu leader Joseph Mathunjwa in the gold sector strike, and as platinum negotiations got underway, even worse conflict was expected. Mathunjwa complained,

“The registrar is inconsistent and unduly interfering in the affairs of Amcu. The inconsistency of the registrar when it comes to the deregistration of trade unions leaves a lot to be desired. There are numerous examples of trade unions and trade union federations who have contravened many prescriptions including financial submissions they were never deregistered or threatened with cancellation of registration. Instead he chooses to focus on Amcu. This is clearly a political agenda.”

Even worse news for Amcu followed two weeks later, when a judge once known for his pro-worker ideological bias, Dennis Davis, ruled against the union’s last-gasp attempt to save jobs by halting Sibanye’s takeover, on grounds of Lonmin’s proximity to bankruptcy:

“Notwithstanding transient fluctuations in the price of platinum group metals and currency fluctuations, Lonmin’s continued existence was in jeopardy and the number of job losses that Sibanye and Lonmin projected as a result of the merger was rational. At best, Lonmin would continue to ‘tread water’, that is, if it was not placed into business rescue, which, if it occurred, would hold significant risk for 32,000 jobs.”

Within days, a reality check to Davis’ misplaced pity for Lonmin was offered by Business Day’s Ann Crotty:

“In December 2017 Lonmin shareholders, shell-shocked by events dating from even before the Marikana massacre of August 2012, must have been tempted to heave a huge sigh of relief when Sibanye-Stillwater arrived on their doorstep with a share-exchange offer. As could be expected, given that the Sibanye-Stillwater team could smell fear and desperation from the Lonmin camp, the offer was cheeky. It priced in all of Lonmin’s problems, many of which looked near fatal, but was remarkably snoep when it came to the assets, which include a state-of-the-art smelter and two refineries. Lonmin also has an assessed loss of US$1.1bn, extremely valuable for a profit-generating entity. Lonmin has managed to survive through the depths of survived the platinum price weakness and now no longer requires rescuing.”

Indeed Crotty quoted a leading mining analyst critical of the deal, concerned about Froneman’s underpayment to Lonmin’s shareholders, given how much the takeover target’s fortunes had improved over the prior eighteen months: “If anything, the all-share acquisition by Sibanye is increasingly looking like a disguised rights issue by Sibanye to shore up its strained balance sheet and covenant ratios.”

Sensing the unease, Froneman quickly authorised a minor increase in the price and Lonmin chief executive Ben Magara – legally bound to favour the Sibanye takeover – downplayed any expectation that the rising profits he had just registered now merited a rethink of the deal:“Our performance has been impacted by low morale and high management turnover, instability and uncertainty, due to the extended timeline to close the Sibanye-Stillwater transaction caused by Amcu.”

On 24 May, one of the most important South African financiers, Standard Bank, warned shareholders that they were being sold out by US$460 million (instead of US$0.81/share, the price should be US$2.43), “if assets such as the platinum producer’s suspended K4 project, spare processing capacity and a concentrator are factored in.” If more than 25 percent of the shareholders vote no, the merger will fail.

The South African state’s corruption-riddled Public Investment Commission, with 29 percent ownership and thus power to block the sale, has not stated how it will vote, so a high degree of tension looms in London before Tuesday’s meeting.

Resistance ebbs and flows, from the local to global and back

Against mining capital, the politicians and the state stood a variety of disparate organisations: Amcu, Sikhala Sonke and CALS, the church-based Bench Marks Foundation (which in 2017 had begun campaigning for divestment from Lonmin), a Johannesburg-based network of activists known as the Marikana Support Campaign, the EFF, and solidarity activists in Britain and Germany.

In addition to better wages and more community investment, their main post-massacre demands were that Lonmin and the government publicly apologise, pay survivors and widows reparations (civil suits of more than US$70 million have been filed) and declare August 16 a national holiday with a monument at the site of the massacre.

Other concrete grievances were regularly expressed by the Marikana Support Campaign, such as: “No action has been taken against Lonmin directors despite a recommendation for them to be investigated for possible prosecution. President Zuma has sat on the findings of the Claasen Inquiry into Riah Phiyega. In the meantime she has ended her contract and maintained all her benefits.”

Zuma consistently refused to meet these demands, and instead promoted improvement of the living conditions of workers. Government failed to rapidly make mandated compensation payments to the workers and their families – for widows’ and children’s loss of support claims, and for 275 unlawful arrest and detention claims by surviving workers.

In addition, two other international solidarity campaigns continued to put pressure on Lonmin prior to its death. In London, there are regular picketing, film screenings and tours arranged by the Marikana Miners Solidarity Campaign, targeting Lonmin, its institutional owners and its financiers: “London-based asset management funds Investec, Majedie, Schroders, Standard Life and Legal & General who own 44 percent of the corporation. A consortium of banks including Lloyds, the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation and the Royal Bank of Scotland are Lonmin’s biggest lenders.”

Two important activist groups there are the London Mining Network and the student movement Decolonising Environment. And in Germany, the major platinum purchaser Badische Anilin- und Soda-Fabrik (BASF) – Lonmin’s largest single customer, dating back three decades – came under pressure from a “Plough Back the Fruits” campaign of solidarity activists demanding that BASF put pressure on Lonmin to improve workplace and community conditions.

The firm resisted this secondary pressure, but BASF was in 2017 finally compelled to admit, “We note that the development of living conditions for Lonmin workers is not progressing as quickly as one would expect or hope. This is due to the fact that the situation in South Africa is extremely multi-faced and cannot be solved in the short term by one institution alone.”In 2018, a book edited by German and Austrian campaigners, Business as Usual after Marikana, deepened the critique of Lonmin.

But so far, notwithstanding the impressive international solidarity, resolutions of the grievances have not been achieved by the disparate civil society strategies that followed Marikana. One was the demand for higher wages, which the workers were gradually winning. However, the R12 500/month initially demanded in mid-2011, when it amounted to US$1985/month, had shrunk to just US$870/month in mid-2019 due to currency devaluation (from R6.3/US$ to R14,4/US$ in that period). The R12 500 demand was only achieved in 2019, but inflation had eroded that sum by more than a third.

Another strategy was genuine community development, advocated most strongly by Sikhala Sonke women who, in part, attacked the World Bank for its failures, followed by further Bapo Ba Mogale community grievances. Lonmin management repeatedly claimed to have spent more than US$35 million on community housing since 2012, though conceded it had not met the promise of 5500 worker-owned houses because of lack of demand.

Since none of these campaigns for improvements at the point of production (led by Amcu) or labour reproduction (led by Sikhala Sonke) have been satisfactorily achieved, whatcan be learned from these shortcomings?

The 2012-19 era provided dispiriting lessons in power relations thanks to the fragmented, single-issue nature of the attacks on Lonmin, most of which will continue to apply in the Sibanye era, as well as several that require more attention to the 2012 conjuncture for the sake of facilitating the demand for reparations.

To transcend the silo politics, the crucial strategic questions, are what solidarity opportunities for future campaigning might emerge both within the debt-ridden working class as it strives to survive on inadequate wages, and against the rump of Lonmin as captured by Sibanye, its purchasers (BASF and Volkswagen) and its bankers (especially the World Bank)?

Indeed, is nationalisation of the platinum reserves as well as the multinational corporate-owned mining infrastructure feasible – and desirable – in a pre-socialist, neoliberal-nationalist era in which the state continues to be run by Cyril Ramaphosa?

Fighting for a nationalised platinum sector

To prevent the “reloading” of Marikana’s various oppressions, as appears certain today, a much larger accounting of South Africa’s resource-cursed mining sector must be made. To recap, the period since 2012 revealed at least half a dozen underlying curses at Marikana, as well as across what is termed the “Minerals-Energy Complex”:

- political – the obedience of politicians like Ramaphosa and the state security apparatus to the predatory needs of multinational mining capital;

- economic – the tendency to overproduction intrinsic to the capitalist system, especially in times of a commodity super-cycle (2002-11) whose subsequent crash left Lonmin vastly over-exposed;

- financial – usurious microfinance borrowed by mineworkers (leading to extreme borrower desperation by the time of the August 2012 strikes), US$150 million in dubious World Bank ‘development finance’ investment, and chaotic corporate investment given Lonmin’s share price debacle;

- gendered – especially the stressed reproduction of labour and community by women in Marikana’s wretched Nkaneng and Wonderkop shack settlements;

- environmental – extreme degradation within fast-growing peri-urban slums, nearby which minerals are dug and smelted using high-carbon processes that also pollute local water, soil and air; and

- labour-related – platinum rock drill operators’ inadequate wages and deplorable working and residential conditions, especially in comparison to mining executives’ ludicrously generous remuneration: the durability of apartheid-era migrancy, itself a condition dividing workers from the area’s traditional residents along familial, ethnic and (property-related) class lines; intra-union battles which split workers and generated some of the initial 2012 violence, followed by further violence in 2017 including within Amcu; and on-going mass retrenchments due to a (failing) automation strategy.

In future months and years, can these forces find common cause? The underlying principles of Lonmin’s various opponents often seem worlds apart. According to Samantha Hargreaves of the Women in Mining non-governmental organisation (NGO),

“Narrow male-dominated trade union and worker interests mean that hope for a radical resolution lies in the struggles of women in places like Wonderkop. The challenge is linking these with (mainly male) worker struggles and environmentalist solidarity to challenge the extractivist model of development, the social, economic and environmental costs of which are principally borne by working-class and peasant women.”

It may well be, in this context, that both shop-floor and grassroots forces require assistance from institutions with larger agendas, including political parties and even NGOs challenging the broader economic agenda of transnational corporations.

For example, in mid-2015, Lonmin’s tax avoidance was raised by Alternative Information and Democracy Centre (AIDC) director Brian Ashley (a leading Amcu advisor): “As the AIDC, we will pursue a campaign for the company’s licence to be revoked and for the state owned mining company to take over the company… We need to hold these huge corporations to account. You cannot have a company in a country that needs to be rebuilt sucking the resources dry.”

At the same time, the leftist EFF party also demanded mine nationalisation and in the case of the massacre punishment including both jail for Lonmin leaders and compensation: “The EFF will institute a process of reparations against Lonmin to demand reparations and payments of all the families of deceased mineworkers of R10 million (then US$1.1 million) per family and R5 million (US$0.55 million) per injured worker.”

Even the centre-right Democratic Alliance party announced that it also supported forcing Lonmin to compensate massacre victims’ families.

With Lonmin unable to continue as a going concern, much bigger questions about political strategy can be raised. To think creatively about the options for Lonmin (via Sibanye) not only requires a revived debate about whether or not to take away the firm’s mining license (which, indeed, was threatened by Pretoria in late 2016 due to Lonmin’s default on its Social and Labour Plan) or to nationalise it with – or preferably without (given such immense liabilities) – compensation to traditional overseas owners (as the EFF argue).

But setting aside the particular problems at Marikana, the disastrous recent period of mining capital’s over-accumulation and ruinous competition also compels much wider considerations on the need for new priorities that would radically change the corporate financing parameters now in place. These might include:

- developing a world platinum cartel centred in South Africa;

- establishing a genuinely green economic strategy to move the Minerals Energy Complex away from its traditional roots in coal, iron ore, manganese, gold and diamonds (and not simply to hydrogen fuel cells for individualised electric vehicle production);

- incorporating natural capital accounting into state (and corporate) decision-making so that the true costs and benefits of mining can finally be understood in full cost-accounting terms; and ultimately;

- ensuring a ‘just transition’ to low-carbon, post-extractivist economic activities that are especially friendly to women’s needs – within not just the sphere of production but also the reproduction of society, as the AIDC “Million Climate Jobs” campaign advocates.

These are the kinds of strategic questions that can be raised not only thanks to injustices that continue at Marikana, but also because the specific problems of microfinance, development finance and corporate finance confirm the power but also the overlapping, interlocking vulnerabilities associated with Lonmin’s historic abuse of people and planet (and Sibanye’s likely amplification of these).

However, the vulnerabilities even huge mining corporations face have generated mainly the kinds of fragmented campaigns for reform discussed above. As the limits of reformist strategies are reached in each of these, it is still possible for much greater unity to be established between disparate groups of mining capital’s victims.

Since these victims soon include investors representing South Africa’s large civil service as well as financiers, it will be up to the grassroots, shop-floor and environmental activists to ensure that an even more exploitative regime of extraction in the platinum belt does not emerge in coming years.

Moreover, so as to lessen vulnerability to volatile world capitalist markets, it is long overdue for South Africa (with 88 percent of world reserves) to join Russian and Zimbabwean authorities in a world platinum cartel, about which formal discussions began in 2013 amid the first round of platinum gluts.

In the process, a genuinely green strategy for the region should move the economy away from overdependence upon traditional coal, iron ore, manganese, gold and diamonds exports, and ensure a ‘Just Transition’ to post-‘extractivist’ economic activities in line with South Africa’s growing climate mitigation and adaptation imperatives. As Sikhala Sonke and allies point out, the latter should be especially friendly to women’s needs, within not just the sphere of production but also the reproduction of society.

As for the trade union that is most popular in Marikana, Amcu, Mathunjwa has eloquently explained the workers’ concerns in these terms:

“Just surviving each day is a struggle that denies them the choice of engaging in issues of climate change and the ecological crisis caused by mining and the fossil fuel industry… If we leave it to the market, we will not get to the roots of the climate and environmental crisis and workers will be discarded in the existing mining and energy sectors… We refuse to be made to act like ostriches. There is a climate and ecological crisis. We have a horrific jobs crisis. We need solutions to both. But we need a just transition where no worker loses his or her job without either being skilled and transferred to another industry or is compensated for the rest of their working life. As workers we will not bear the brunt of a crisis we had nothing to do with, except by virtue of the exploitation of our labour.”

The consolidation of Ramaphosa’s power in the 2019 election – thanks to a 58 percent vote, four percent higher than his predecessor Zuma had managed in the 2016 election – and his promise that foreign direct investment would reach US$100 billion within five years, together confirmed how difficult the terrain would be for subaltern forces in coming years.

In the internal fissures facing the ANC, there was no progressive option for Marikana, given how weak the trade union and Communist Party rump supporters had become, not to mention how ambivalent about the anti-Lonmin struggle they were given NUM’s 2012 defeat there and Amcu’s rise.

Froneman’s anticipated closure of platinum shafts at Lonmin Marikana operations (with the loss of 12 000 mineworker), and the shift of the big smelter there into a site for Sibanye’s cheaper operations to process their ore, will see the fading of any residual hope retained by workers and communities. Internecine violence between Amcu and NUM rose to new heights in early 2019 at Sibanye’s gold mines, but could get worse in the platinum fields, as the latter union seeks to reclaim its old ground, especially if the former is deregistered.

These are very similar tensions compared to the conditions that in mid-2012 confronted Marikana’s activists. They faced the loaded weapons of Lonmin and its police allies – and didn’t flinch. Will they do so again, now that Marikana’s rulers are reloading?

*Professor Patrick Bond teaches political economy at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. For a full account including references, contact [email protected].