AfCFTA: World’s largest free trade area born—Africa’s game changer

African heads of state and government have recently signed what is now the world’s largest free trade area known as African Continental Free Trade Area. While the excitement is still in the air, it is important to reflect on what this landmark step means concretely, and also suggest some areas that need special attention.

Introduction

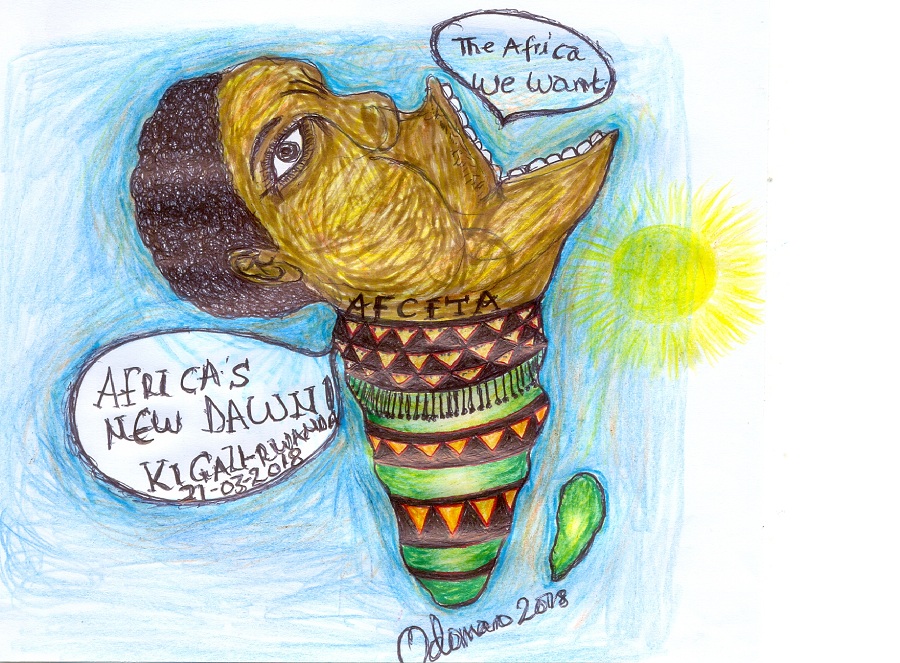

It is 21 March 2018, in Rwanda’s sparklingly clean capital city Kigali. 44 African heads of state and government or their representatives gathered to sign what is now the world’s largest free trade area known as African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). African leaders in the spirit of pan-Africanism have time around done us proud—never mind the 11 who have not yet signed the much-awaited game changer in Africa’s structural transformation. While the excitement is still in the air, it is important to reflect on what this landmark step in the implementation of Agenda 2063 means concretely, and also suggest some areas that need special attention.

Afro-pessimists beware! A trading block of close to 1.3 billion people, about 60 percent of whom are young, restless, and innovative youth, is a force to reckon with. We can safely conclude that finally the African “giant elephant” that has been sleeping in Africa’s tropical forests and grasslands has woken up and no one can stop it. To put it simply, once the AfCFTA treaty is ratified by the respective African parliaments, African goods, services, people and ideas will freely roam the cradle of humanity from Cape to Cairo, from Somalia to Nigeria (I am still puzzled why Africa’s most populous country of over 180 million people can hesitate to sign the free trade treaty). The benefits of a whole continental trading block are unfathomable.

Peace and political dividends to be reaped from a large African market can also not be underestimated. With a sense of common purpose, unity, and free movement of African people both at home and in diaspora, this is the best time to celebrate Africanity. An era of African renaissance and Afro-optimism has dawned. This momentum should be sustained.

Background to AfCFTA

The quest for a continental free trade area is part of the pan-African dream that dates back to luminaries such as George Padmore, Du Bois, Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, Jomo Kenyatta, Albert Lithuli, Julius Nyerere, Frantz Fanon, Amilcar Cabral, to name just a few. The philosophical framework that underpins AfCFTA is clearly pan-Africanism. Issa Shivji speaks of pan-Africanism with passion thus: “It is the Africanness of my village which binds us emotionally and arouses the whole bundle of perceptions, convictions, emotions and feelings associated with the phenomenon called nationalism. Thus African nationalism is Pan-Africanism. There is no, and cannot be, African nationalism outside of, apart from, or different from Pan-Africanism.”[[i]] This political emotion and intense feeling of being African gave rise to a radical movement that consolidated political solidarity for all African peoples.

As Africa sought to free itself from the forces of colonialism, African nationalist thought emerged as a force against imperialism, whose main goal was African unity. It is no surprise that Pan-Africanism was developed by Africans in diaspora in the 19th century by famous Afro-Americans as well as Afro-Caribbeans like Henry Sylvester Williams, George Padmore, W.E.B. Du Bois and C. L. R. James. Key issues at that time revolved around cultural and racial concerns, aiming at racial equality and non-discrimination. Some brief highlights of Pan-African Congresses will suffice. The 1923 congress, stated: “In fine, we ask in tall the world, that black folk be treated as men.” The Pan-African Federation was formed in Britain in 1945, that later organised the Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester in the same year. The Fifth Pan-African Congress demanded Africa’s independence and coined the slogan: “African for Africans.” [It is] important to recognise that the leading organisers of this congress were Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and Jomo Kenyatta from Kenya. [It is also worth to] note how the economic aspect of Pan-Africanism is well captured by one of the resolutions of the 5th Pan-African Congress: “We condemn the monopoly of capital and the rule of private wealth and industry for private profit alone. We welcome economic democracy as the only real democracy.”

While the passion for African unity was not in doubt among post-colonial African leaders, the means to attain this unity were heavily contested. Nkrumah, on the one hand, wanted a full-fledged political African union that he even termed the United States of Africa. Nyerere, on the other hand, wanted a gradual unification that would start from below through regional blocks such as the East African Community (EAC). After several conferences and with Ghana’s independence in 1957, the Charter of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) was adopted in May 1961, by 32 African states in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. With the OAU born, and several African countries independent, the cry for Pan-Africanism got toned down with the respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty of African states. Also the principle of non-interference in each other’s internal affairs was adopted.

The main challenge that post-colonial African leaders failed to resolve was on how to liberate Africa from colonialism and its impact without at the same time working for African unity. Nkrumah and some others had rightly observed that you couldn’t address colonialism without dismantling the balkanisation of Africa into small unviable states. The other major challenge still facing the African continent as far as the Pan-African vision is: what should come first—political union or economic union? Nkrumah had simplified it thus: “Seek you first the political union and the economic union shall be added thereunto.” With the African Union (AU) Constitutive Act adopted in 2001, the next task was economic union. The Kigali Declaration of 21 March 2018, at the 10th Extraordinary Summit of the AU, is effectively the most decisive step towards economic union of the African continent.

AfCFTA has taken a while to come. The original vision was contained in the Lagos Plan of Action that was adopted by African heads of state and government in 1980. 11 years later in 1991, the Abuja Treaty established the African Economic Community. Since then nothing much had taken place, except the much-celebrated Agenda 2063. A look at some major aspirations of Agenda 2063 demonstrates how attempts have been made to realise the age-old Pan-African vision: [[ii]] Aspiration 1. A prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable development; Aspiration 2. An integrated continent, politically united and based on the ideals of Pan Africanism; Aspiration 7. Africa as a strong, united, resilient and influential global partner and player. This 7th aspiration is the one that is closely linked to the birth of AfCFTA.

What AfCFTA means for the African continent

It is estimated that AfCFTA will bring together 55 AU member states, whose combined gross domestic product (GDP) is more than US $ 2 trillion. Intra-African trade is expected to grow by over 50 percent in the days ahead. Removing trade barriers among African states will no doubt enhance African integration, by reducing trade tariffs, and this will in the long run, enable Africa to compete with larger economies of the world such as China, India, the United States of America and the European Union (EU). The exploitation of small African countries with their low bargaining power will come to an end. The fact that some few African countries have large economies and will therefore have some advantage over the small economies, is an issue to contend with. But this is true even in the EU. In the broader scheme of things, all will benefit. The cost of intra-African trade is by far lower than African countries engaging in overseas trade. But the greatest benefit of AfCFTA is the free movement of peoples, goods and services among African countries.

Africa is also expected to be home of close to 2.5 billion people by 2050. With what has been termed a demographic dividend, Africa could also turn out to be the continent with the highest working age population of 26 percent worldwide. It is also estimated that Africa’s economy will grow twice as fast as that of the developed world. The benefits of economic integration that AfCFTA is all about have been praised by Faki Mahamat, the Chairperson of the AU Commission: “Economic integration thus responds not only to aspirations born out of Pan-Africanism, but also a practical imperative linked to the economic viability of the continent.” Why should Africans doing business in Africa pay higher tariffs than when they are exporting outside Africa?

As for President Paul Kagame who hosted the historical summit in Kigali, he sees greater benefits including dignity and prosperity for all Africans: “What is at stake is the dignity and well-being of Africa’s farmers, workers, and entrepreneurs, particularly women and youth. The promise of trade and free movement is prosperity for all Africans, because we are prioritising the production of value-added goods and services that are ‘Made in Africa.’” And when President Kagame who now is Chair of AU speaks, you better take his word seriously. He is also working very hard to ensure that the AU becomes self-reliant in terms of funding its major programmes. If he can bring the same rigour and order he has established in post-genocide Rwanda to the entire African continent, the dignity of the African people can be restored sooner than we anticipated.

A borderless Africa has been born in AfCFTA. Once at least 22 countries have ratified the treaty, it takes effect. This may take some months before we can traverse the huge continent, but the crucial step has been taken.

How to maximise the benefits of AfCFTA?

In line with the AU Agenda 2063 the strategic areas that all our countries should focus on should include the following: science, technology and innovation; modern agriculture for increased productivity; world-class infrastructure across Africa (hydro electric dams, high speed trains, information and communication technologies penetration, open skies for African airlines); skilled personnel trained in information technology and innovation.

Africa still lags behind in industrialisation. Some policies are being worked on to change this situation. [[iii]] For massive industrialisation to happen across Africa, mechanisms for innovative financing of Africa are needed. [[iv]] Often times financing is not well-coordinated.

Development partners who are flocking to Africa will also need to harmonise their funding policies to the broader aspirations of the continent as an economic block. Among the innovative strategies for financing Africa are: domestic financial resource mobilisation (oil revenues, metallic minerals); stopping illicit financial flows; and private equity.

In terms of capacity, Africa has quite a number of capacity building institutions such as the African Capacity Building Foundation (ACBF) based in Harare, Zimbabwe, the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Institute of Peace and Security Studies (IPSS) based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) and United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Then add hundreds of African universities. If these institutions were to collaborate and harmonise their research and policy studies with a focus on African solutions, a lot can be achieved. One gets an impression that institutions such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), AfDB, UNDP, UNECA, etc., are steering the African continent in divergent development and policy directions. Why do development policies on Africa keep on changing when the challenges of poverty, inequality, illiteracy and disease are constant?

With the shift from Millennium Development Goals (MDGS) to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a new approach that emphasises an integrated and coherent approach to sustainable development in Africa has been adopted. [[v]] Even though some of these approaches reflect elements of the neoliberal agenda, Africa can still make good use of these approaches. The eight MDGs of eradicating extreme hunger and poverty, achieving universal primary education, promoting gender equality and empowering women, reducing child mortality, improving maternal health, combating HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases, ensuring environmental sustainability, and developing a global partnership for development, should not be abandoned. AfCFTA will in fact make it easier for individual countries to meet these goals much faster.

There is no need to reinvent the wheel when it comes to development policies and priorities. Among the impressive list of the 17 SDGs I consider the following to be given priority: [[vi]] Goal 1—end poverty in all its forms everywhere (it is no longer poverty alleviation) by 2030; Goal 2—end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture; Goal 4—ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all (free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education); Goal 5—achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls; Goal 7—ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all; Goal 9—build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and foster innovation (including regional and trans border infrastructure); Goal 10—reduce inequality within and among countries; Goal 11—make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable; Goal 15—protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity; Goal 16—promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels (includes rule of law, reduction of illicit financial and arms flows, strengthen the recovery and return of stolen assets, reduction of corruption and bribery, effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels).

To these we could add massive investment in tourism and take advantage of free movement of peoples. Intra-African tourism needs to be enhanced. Although date is not readily available, not many Africans are known to make tourist trips within Africa due to visa restriction and cost of air travel. This will hopefully improve once the free movement of people is facilitated through a visa-on-arrival policy across Africa.

Within regard to industrialisation and urbanisation policy in Africa, UNECA has done some impressive research that just needs to be translated into policies for each country: Urbanisation and Industrialisation for Africa’s Transformation (2017); Transformative Industrial Policy for Africa (2016); and Greening Africa’s Industrialisation (2016).

Another major area of focus will be regional integration that can enhance innovation and competitiveness. Some of the already existing regional blocs such as the EAC, the Economic Community of West African States, the Community of Sahel-Saharan States, and Arab Maghreb Union have ratified protocols on free movement of persons up to more than 60 percent share. [[vii]] And as Africa becomes a more attractive investment destination, it is important to pay close attention to investment policies as well as investment treaties within Africa and how they affect regional integration. [[viii]] Reforms will be carried out to improve investment climate and especially remove protectionist policies, unpredictable political transitions and enhance the rule of law. The challenge of some agreements that tend to offer more protection and rights to foreign investors (at times done through corrupt deals) needs to be addressed urgently.

Africa still faces the challenge of corruption and governance. It is hoped that AfCFTA will not be used as a vehicle for the free movement of ill-gotten wealth across the continent. That is why governance has to be taken seriously. The policy recommendations of Africa Governance Report IV are therefore commendable: enhancing ownership and participation in development planning; improving transparency and accountability; building credible governance institutions; and improving the regional and global governance architecture.[[ix]]

African economies need macroeconomic policies that will enable structural economic transformation to take place. This will require an honest evaluation of the previous development policy frameworks since the 1960s. What will macroeconomic policies address? [[x]] First, there is need to scale up public investment and provision of public goods. Second, there is need to ensure macro stability to attract and sustain private investment. Third, the need to coordinate investment and other development policies. Fourth the need to mobilise local resources and reduce aid dependence. And finally, the need to secure fiscal sustainability through fiscal legitimacy. The crucial issue that UNECA recommends for maximising benefits of regional integration aptly stated thus: “To maximise benefits from regional integration and pan-African integration, development strategy and investment should be well coordinated with each regional bloc and between them (that is, continent-wide), allowing dense production networks to generate secure jobs as evenly as possible across the region.”[[xi]]

Finally, there is need for listening to African-focused intelligentsia and Afropolitans, who can offer constructive reflection on policy and practice both theoretically and empirically. There are quite of a number of research centres across Africa doing this sort of thing, but they need to be better coordinated and avoid duplication. Such centres include the Organisation for Social Science Research in Eastern and Southern Africa and the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa. Some of the policy issues that need rigorous analysis with policy implications include: [[xii]] the role of higher education in Africa; land ownership and land-grabbing; gender inclusion; investment by the intellectual diaspora; globalisation; migration; rural-urban migration; agriculture and Africa’s structural transformation; the green economy and Africa’s economic transformation; and private-public partnership.

Conclusion: Enablers and spoilers

Now that AfCFTA is born, the work of implementation begins. The first enabler is of course the ratification of the treaty by the respective parliaments. Second, the self-inflicted visa restrictions on fellow Africans has to be replaced by free visa-on-arrival for all Africans across the continent. Third, Africans in the diaspora also need to be part of this new dawn and bring home their business and intellectual skills they have honed for decades abroad. Fourth, full participation of the civil society and private sector in the implementation of AfCFTA is a must. Regional integration is a project for all and not just for the few elite or those in power. Fifth, Internet connectivity and mobile telephones are a major enabler and everything should be done to ensure that the respective countries are well-connected.

What of spoilers? There are those who will want to spoil the party of regional integration. First, the numerous armed militias roaming across the continent especially in Somalia, Central Africa, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria’s Boko Haram, are a major negative force and need concerted efforts. Also to watch out for are Islamic Militants such as Al Shabab in Somalia, who will want to once in a while make attacks on travellers. The other category of spoilers are power-hungry politicians who will use AfCFTA to further their selfish political agenda instead of promoting the common good of their respective countries. It is such people who will make use of the freedom of movement of goods, services and people to engage in illicit financial flows.

Some of the African countries that are too protective of their economies and are following a state-controlled economic model will still want to restrict use of telecommunication, media and control foreign currency as well as the financial sector. Some standard rules and regulations should be agreed upon on these matters.

If Africa embraces AfCFTA with enthusiasm and puts in place mechanisms to maximise the benefits that have been highlighted, there is no reason why Africa will not claim the 21st century. Let all Afro-optimists mobilise their energies and resources around this new concept of AfCFTA. Africa is on the verge of an economic take off. Remember that there is always something new out of Africa.

* Doctor Odomaro Mubangizi teaches social and political philosophy at the Institute of Philosophy and Theology in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia where he is also Dean of the Department of Philosophy. He is also Editor of Justice, Peace and Environment Bulletin.

[i] Issa G. Shivji, Where is Uhuru? Reflections on the Struggle for Democracy in Africa (Nairobi: Pambazuka Press, 2009), p. 197.

[ii] See Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want, First Ten-Year Implementation Plan 2014-2023. (Addis Ababa: AU, 2015), Pp. 45-91.

[iii] See Arkebe Oqubay, Made in Africa: Industrial Policy in Ethiopia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

[iv] See Abdalla Hamdok (Ed), Innovative Financing for the Economic Transformation of Africa, (Addis Ababa: UNECA, 2015).

[v] See ECA, AU, ADB, UNDP, MDGS to Agenda 2063/SDGs: Transition Report 2016 (Addis Ababa, 2016).

[vi] See ibid., pp. 114-134.

[vii] African Union, UNECA, ADB, Innovation, Competitiveness and Regional Integration: Assessing Regional Integration in Africa VII (Addis Ababa: ECA, 2016), p. 29

[viii] See UNECA, Investment Policies and Bilateral Investment Treaties in Africa (Addis Ababa: ECA, 2016).

[ix] UNECA, Measuring Corruption in Africa: The International Dimension Matters. African Governance Report IV (Addis Ababa: ECA, 2016), pp. xiv-xv.

[x] See UNECA, Macroeconomic Policy and Structural Transformation of African Economies (Addis Ababa: ECA, 2016), pp. 35- 52.

[xi] Ibid., p. 15.

[xii] See Journal of African Transformation: Reflections on Policy and Practice, Volume 1, No. 1, 2015, Volume 1, No. 2, 2015.