On history and reparations: A response to Henry Louis Gates

Writing in response to a New York Times article by Henry Louis Gates, Antumi Toasijé strongly challenges the view that we should simply 'end the slavery blame game'.

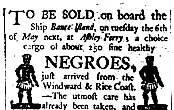

Most of African descendants and many of the non-African descendants have heard about the 'gates of no return'. One of those gates is located on the island of Gorée in present-day Senegal. It is the gate that connects the dungeons where enslaved peoples from north-west Africa were held before embarking to America, Europe and Asia. In fact, there is a gate of no return on almost every fortress or castle ordered to be built by Europeans and Arabs along the African coasts. The gates of no return symbolise the horror of the crime of slavery itself, because they represented the end of most of the possibilities to continue being full human beings. There is no consensus on how many victims passed through those gates in four centuries and were forced to become three-fifths of a human to serve, breed and sustain supposedly full human beings. Maybe they were dozens of millions. From there they were dispossessed of identity and individuality; from their own cultures they were turned into 'negroes', assimilated into the European structure of thinking and brought in as the lowest rung of the European social system to build the contemporary world.

The debate around reparations has several misinterpretations and manipulations; in this debate you can find many scholars from several disciplines and the general public. Non-professional historians have often made enormous contributions and advances to the historical sciences, but have also fallen under contra-factualist and diachronic interpretations. As the dialectical combatants in this debate on reparations frequently ignore certain historical facts and some of the existing legal potentials and constrictions over the issue that are not well-known to the public, the confusion tends to focus the debate on race relations in today’s world rather than the crime of slavery itself. One of the biggest misinterpretations of history is to include the race and geographical continental factors in time lapses or cultural areas where it is anachronistic; doing so is an untrustworthy exercise in alternative history in the worst sense. The categories today known as 'white' or 'black' and 'European' or 'African' have an historical genesis linked to the implementation of the contemporary European schema of thinking around the globe; ignorance of this can bring mystification to the past canvas. This is why the statements of Henry Louis Gates, writing in The New York Times in an article dated 22 April 2010 and entitled 'Ending the slavery blame-game' are so precarious, showing very much that he is an African-American from the 20th and 21st centuries universalising European thoughts.

Prior to the almost successful annihilation of African cultural and personal identities in the hands of the enslavers, the enslaved peoples perceived themselves not as members of a race or a continent but members of a nation, kingdom or rural culture – if there was any antagonism between black Africans and white Europeans it was based on specific facts much more than in pseudoscientific theories. To blame some Africans for enslaving other Africans in those days instead of enslaving peoples from other continents is as absurd in historical terms as to blame Europeans for having wars inside Europe for centuries or thousands of years: 'How could whites do such a thing to whites?' The racial and racist views are a consequence of the slavery system rather than a cause, and of course are totally western European in origin. If Europeans of the 19th century had a generalised, negative depiction of black peoples, it was created by them under the conditions of slavery as an economic and ideological system. The fact that the reparations movement has been led from the beginning by peoples of African descent does not mean that it only concerns 'blacks' against 'whites'. Of course, the gross majority of the enslaved peoples of the modern era were black Africans, and of course the majority of the promoters and usufructuaries of this system where whites, European and Euro-American, but this does not mean that the reparations movement is only for those whites who enslaved Africans. This is the weakest argument ever used against a social process. Can you imagine blaming the achievements of the civil rights movements in the United States by saying that some black men were policemen at the time? This movement as the reparations movement is much more universal than racial. The structure of thinking that denies this is a typical contamination of the idea that black peoples are not humanity, but when it comes to achievements that are pursued from the white side, nobody questions that they are universal; these are typical arguments of this epoch.

So if things seem to be so relative, what is the basis of the reparations movement? Of course it is the crime itself, regardless of the race or nationality of the perpetrators. I do repeat: the perpetrators were almost all whites, but I don’t think the supporters of the reparations movements can or want to judge this racial or continental background on a serious judicial basis. Today there are not living testimonies of this horror from one side or the other. The crime is being judged by its consequences, and of course the present inequalities existent between Africa and Europe have much more to do with slavery and colonialism, produced by Europeans, than the crimes or mistakes of Africans themselves. Moreover, black Africans never went to European ports to massively enslave or colonise Europe's peoples, and if this did happen in a very far past somewhere, its social costs are not visible today. Some of the African kingdoms participating in the crime have expressed their sorrow or even accepted responsibilities. I know, as an African descendant of the 21st century, that they owe me something and I know they are willing to pay. But there is no way to compare the power and wealth acquired by these political entities with the little or no participation of African post-colonial state politics with the British crown and the Spanish crown, for instance, that exist today and have real political power. Let’s just say one thing more here: the states of Benin or Ghana are also creations of Europeans and by the moment of their independence had little bond with the enslaving royal entities on their soils.

The strongest legal basis to repair the crimes are twofold. The first is the conscience, especially from the European side, of committing a crime. This can be seen from the liberal revolutions of the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries; documentation on this is overwhelming. The principal pro-slavery argument in those days was of an economic nature, this is why slavery continued being perpetrated by Europeans and Euro-Americans, even at a very advanced date when it was widely known and accepted that it was a crime. For instance, Spain continued practising slavery until 1886 and kidnapping people from Africa until the 1880s, but their first treaty against the human trade dates back to 1817. Despite this, in the period from 1817 to 1880 Spanish vessels enslaved about 700,000 peoples from Africa. And of course more than one million Africans in Cuba were exposed to the brutality of forced labour. Let’s not forget, to be precise, that reparations are growing from the inside of the European system. For instance, it is the Rome Statute of the International Penal Court that say that slavery is a crime against humanity. The second legal fundament is the social cost; the actual persons involved in the crime are the companies that were founded in that era – banks, insurance companies, transportation companies – and an extremely large number of the long-lasting companies working on various fields existing today were founded and grew up with the benefits of the major crime of human history.

I’m a self-satisfied black man by today’s standards and I have the perspective of what Maafa is and was, but even if I wasn’t I could seriously say that the reparations movement has a strong legal and moral basis. Reparations are useful to prevent future crimes and they will help to end present crimes, asymmetries and false beliefs.

BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Antumi Toasijé is a historian and the director of the Pan-African Studies Centre in Spain.

* Please send comments to [email protected] or comment online at Pambazuka News.