The benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism: An integral part of the South African history

Since 1994 South Africa has been unable to seriously change the national socio-economic direction in the interest of the majority of the people. The end of apartheid has helped to increase SA’s integration into global capitalism. The benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism are mass poverty for the majority and wealth and privileges for the powerful minority, which includes a few blacks.

There has been the dialectical and organic relationship between the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism in South Africa since their inception in the country. The capture of the interlinkages between these problems in the South African history for their concrete understanding and resolution is through the theoretical use of the relationship between race and class and the theoretical and practical recognition of the primacy of class over race in South Africa. Capitalism since its inception in South Africa has constituted the primary or irreconcilable contradiction with the masses of its exploited people. This work uses the dialectical relationship between race and class to explain the relationship between the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism in the South African political economy.

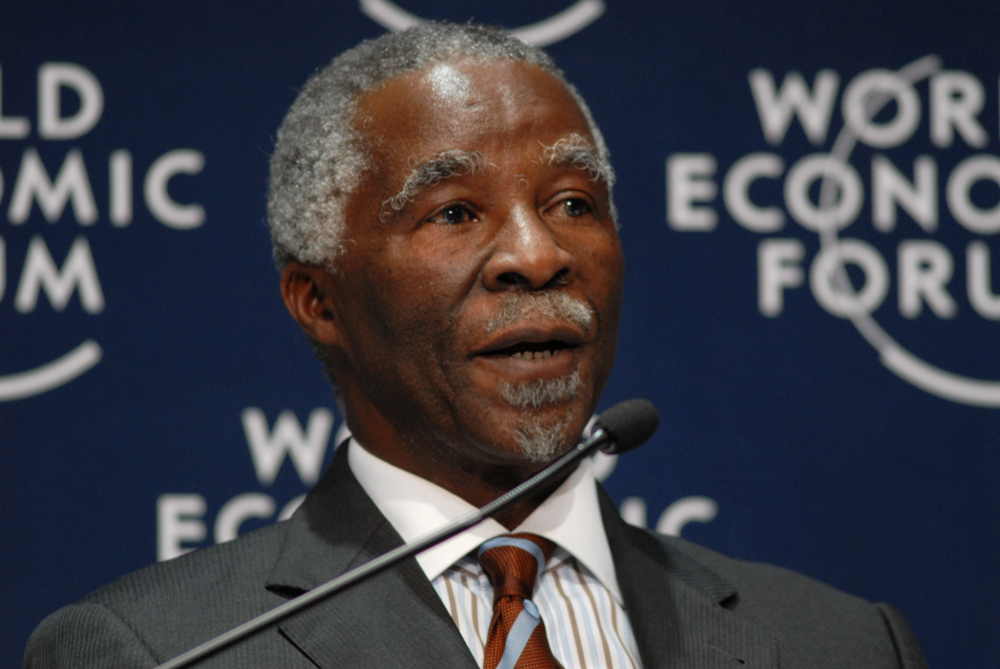

Thabo Mbeki, on the proposed domestic and foreign policies of the post-apartheid South Africa, examined key characteristic features of apartheid South Africa. He pointed out that the provision of “a penetrating understanding” of South Africa is the task requiring that we look into its past. According to him, to have this understanding, we must appreciate the reality that we are dealing with a class society in which “the capitalists, the bourgeoisie are the dominant class.” The dominance or “supremacy of the bourgeoisie” was conditioning “the state, other forms of social organisation and social ideas” in the South African society. This essential feature of South Africa was characteristic of other societies in which the bourgeoisie was dominant. Providing a socio-historical background of South Africa as a class society, he maintained that:

‘The landing of the employees of the Dutch East India Company at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652 represented in embryo the emergence of class society in our country. And that class society was bourgeois society in its infancy. The settlers of 1652 were brought to South Africa by the dictates of the brutal period of the birth of the capitalist class which has been characterised as the stage of the primitive accumulation.’[1]

Mbeki excluded Karl Marx’s statement: ‘on their heels treads the commercial war of the European nations, with the globe for a theatre’ which is immediately after he pointed out the characteristic features of the process of the primitive accumulation of capital.

Mbeki quoted Marx in explaining ‘the expropriation of the African peasantry’ or ‘the expropriation of the great mass of the people from the soil, from the means of subsistence and from the means of labour.’[2] This quotation is as follows:

‘The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins, signalised the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production. These idyllic proceedings are the chief momenta of primitive accumulation. (Capital, Vol. 1, p. 703). … the transformation of the individualised and scattered means of production into socially concentrated ones, of the pigmy property of the many into the huge property of the few, the expropriation of the great mass of the people from the soil, from the means of subsistence, and from the means of labour, this fearful and painful expropriation of the mass of the people forms the prelude to the history of capital. It comprises a series of forcible methods ... The expropriation of the immediate producers was accomplished with merciless vandalism, and under the stimulus of passions the most infamous, the most sordid, the pettiest, the most meanly odious’ (p. 714).[3]

This quotation is important for several key reasons. It enables us to fully understand, firstly, why the labourers of the Dutch East India Company landed at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652. Second, that violent methods were used in the "fearful and painful expropriation" of the masses of the South African people. Third, that they were forcibly separated from the means of production, distribution and exchange. Fourth, why the first group of slaves were brought to the Cape to serve the interests of the forces of imperialism. Fifth, why South Africa became thrust directly into wars between Britain and Holland in their intensified competitive expansion on an international scale. This quotation enables us to fully understand that oppression and exploitation of the masses of the colonised and enslaved people by imperialist powers provided the socio-political and economic foundation for the rise, growth and dominance of capitalism in its centre. Mbeki’s view of South Africa as a capitalist society under the dominance of the bourgeoisie is a vital contribution to our understanding of the reality that it is not an exception to the strategic working class thesis that capitalism constitutes the primary, irreconcilable or antagonistic contradiction with the masses of the oppressed and exploited people.

Adam Smith’s thesis of the benefits and misfortunes of the colonial conquest of America and the passage to the East Indies through the Cape of Good Hope as the greatest and most important developments in the history of the world provides the socio-historical background of the dialectical and organic relationship between the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism in South Africa. It is useful not only in providing a critical analysis of the dialectical and organic relationship between race and class in South Africa, but also in paving the way for the understanding of the dialectical and organic relationship between the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism as an integral socio-economic part of the South African history.

According to Smith, the colonial conquest of America and the passage to the East Indies through the Cape of Good Hope are some of the greatest and most important developments in the history of the world. ‘The discovery of America and that of a passage to the East Indies by the Cape of Good Hope,’ he wrote, ‘are the two greatest and most important events in the history of mankind.’[4] He continued, pointing out that:

‘Their consequences have already been very great: but, in the short period of between two and three centuries which has elapsed since these discoveries were made, it is impossible that the whole extent of their consequences can have been seen. What benefits, or what misfortunes to mankind may hereafter result from those great events, no human wisdom can foresee.’[5]

Smith later recognised that while the benefits of these two developments went to the decisive minority of the world, their misfortunes went to the decisive majority of the people of the world. In other words, he recognised socio-political and economic problems of imperialism and colonialism and their consequences. He wrote:

‘By uniting, in some measure, the most distant parts of the world, by enabling them to relieve one another’s wants, to increase one another’s enjoyments, and to encourage one another’s industry, their general tendency would seem to be beneficial. To the natives, however, both of the East and West Indies, all the commercial benefits which can have resulted from those events have been sunk and lost in the dreadful misfortunes which they have occasioned.’[6]

Superiority of force

When these ‘discoveries’ were made, ‘Europeans’ were enabled by their possession of ‘the superiority of force’ in committing ‘with impunity every sort of injustice in those remote countries.’[7] This ‘savage injustice’ of the European forces of imperialism and colonialism was an integral part of the organised brutal, violent measures visited upon ‘nations in America’ which ‘were destroyed almost as soon as discovered.’[8] These measures applied to other colonised countries. According to Smith, they were ‘ruinous and destructive to several of those unfortunate countries.’[9]

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels agreed with Smith on the decisive role that the colonial conquest of America and the passage to the East Indies through the Cape of Good Hope played in the development of capitalism. They pointed out that:

‘The discovery of America, the rounding of the Cape, opened up fresh ground for the rising bourgeoisie. The East-Indian and Chinese markets, the colonisation of America, trade with the colonies, the increase in the means of exchange and in commodities generally, gave to commerce, to navigation, to industry, an impulse never before known, and thereby, to the revolutionary element in the tottering feudal society, a rapid development.’[10]

As organic intellectuals of the struggle to establish community as the basis of social existence whose essence is socio-political and economic equality, Marx and Engels were clear that arising from the dialectically and organically linked benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism was the creation of the world reflecting the image of the centre of capitalism. The benefits and misfortunes of imperialism and colonialism have dialectically and organically led to the existence of the centre and the periphery of capitalism. The dialectical and organic creation and sustenance of these links of the imperialist chain are critical to the concrete understanding of the mechanisms of exploitation of finance capital in its global operations in the dominated links or the developing countries. Global capitalism, referred to by Sven Beckert as war capitalism,[11] depends on the control, domination and exploitation it exercises over human, natural, material and financial resources of these countries which include South Africa. That the relations, institutions and structures upon which international finance capital depends could never have been established, maintained and sustained without human, natural, material and financial resources of these countries is of theoretical and practical importance to the understanding of this dependence.[12] The process of colonialism constituted the base of the mechanisms of international finance capital controlled from the centre of capitalism. The existence of neo-colonialism is the material support of the fact that these relations, institutions and structures of control, domination and exploitation are still in place.

Throughout the whole socio-historical phase of capitalist development from mercantilist imperialism, through free trade imperialism and financial imperialism, to the present period of multilateral imperialism, South Africa, according to Ngugi wa Thiong’o, served as ‘a mirror of the emergence of the modern world.’[13] It executed this task by embodying ‘more intensively than most the consequence of the benefits’ of capitalism and racism ‘to a white minority linked to Europe’ and ‘the misfortunes, to the majority linked to the rest of Africa and Asia, with the minority trying to create a South Africa after its image, which it also saw as representative of what it called Western civilization.’[14] South Africa ‘was also to embody the resistance against the negative consequences’ of capitalist ‘modernity,’ and in ‘its history we see the clashes and interactions of race, class, gender, ethnicity, religion and the social forces that bedevil the world today.’[15]

These ‘clashes and interactions of race, class, gender, ethnicity, religion and social forces’ bedeviling South Africa today constitute challenges faced in the struggle against racism and capitalism.

Race and class in South Africa

The class question in South Africa has key aspects of the race question. There are the dialectical and organic relationship between race and class. Capital and labour in South Africa are socio-historical formations of class and race. There is the articulated combination of the struggle against racism and the struggle against capitalism. This socio-historical development is the consequence of the dialectical and organic relationship between race and class in the country since the inception of colonialism and capitalism. This reality is articulated by wa Thiong’o as follows:

‘South Africa as the site of concentration of both domination and resistance was to mirror the worldwide struggles between capital and labour, and between the colonising and the colonised. For Africa, let’s face it, South African history, from Vasco da Gama’s landing at the Cape in 1498 to its liberation in 1994, frames all modern social struggles, certainly black struggles. If the struggle, often fought out with swords, between racialised capital and racialised labour was about wealth and power, it was also a battle over image, often fought out with words.’[16]

The issue of the struggle between ‘racialised capital and racialised labour’ has been and continues being of theoretical and practical importance in the understanding of the relationship between the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism in the present South Africa. In other words, the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism in South Africa have been having not only the class factor, but also the racial factor. It is for this reason that the relationship between race and class should be weaved without departing from the importance of the racial factor is of theoretical and practical importance in the South African political economy.

The existence of the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism and dialectical and organic relationship between the struggle against capitalism and the struggle against racism in South Africa have been such that the South African revolutionary and progressive forces should dialectically weave the relationship between race and class and never depart from the importance of the racial factor in the South African politics of the structural socio-economic change even before 1994. This reality was supported by the African National Congress (ANC) in its view of the South African national liberation struggle in 1970 as follows:

‘In our country – more than in any other part of the oppressed world – it is inconceivable for liberation to have meaning without a return of the wealth of the land to the people as a whole. It is therefore a fundamental feature of our strategy that victory must embrace more than formal political democracy. To allow the existing economic forces to retain their interests intact is to feed the root of racial supremacy and does not represent even the shadow of liberation.

‘Our drive towards national emancipation is therefore in a very real way bound up with economic emancipation. We have suffered more than just national humiliation. Our people are deprived of their due in the country’s wealth; their skills have been suppressed and poverty and starvation has been their life experience. The correction of these centuries-old economic injustices lies at the very core of our national aspirations. We do not underestimate the complexities which will face a people’s government during the transformation period nor the enormity of the problems of meeting economic needs of the mass of the oppressed people. But one thing is certain – in our land this cannot be effectively tackled unless the basic wealth and the basic resources are at the disposal of the people as a whole and are not manipulated by sections or individuals be they White or Black.’[17]

Articulating this reality, Joe Slovo maintained that:

‘The elimination of national inequality, if it is to be more than a mere gesture, involves a complete change of the way in which the country’s wealth is appropriated. This must surely be the major premise of every social group or class in the subordinate majority, even if its ideology is limited solely to an urge for national vindication. This premise bears on the correction of historical injustice stemming from conquest; it is concerned with the fundamental source of existing grievance, and it has vital relevance to the question of future power relationships. If every racist statute were to be repealed tomorrow, leaving the economic status quo undisturbed, ‘white domination’ in its most essential aspects would remain.’[18]

This articulation of the dialectical and organic relationship between the struggle against racism and the struggle against capitalism and the relationship between race and class by the ANC and Slovo in the service of the structural socio-economic change has been of strategic importance in the task to solve the problem of the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism even before 1994. It pointed to the possibility of capitalism structurally buttressing racism in the post-apartheid South Africa if determined efforts were not to be made to achieve the structural socio-economic change upon the end of the apartheid rule.

Deracialisation of the economy and society

Since 1994, the political leaders of South Africa have been attempting to solve the problem of the national question through ‘the deracialisation of the economy and society.’[19] How to solve he national question without solving the problem of the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism in South Africa? The problem of the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism is in essence the problem of the national question in the country. Thabo Mbeki played a leading role in the formulation, adoption and implementation of the national economic policy since 1994. He declared that the struggle ‘against racism in our country must include the objective of creating a black bourgeoisie.’ [20] He called upon blacks to support the creation and consolidation of the black bourgeoisie in the continued struggle to end racism. The national task to ‘create and strengthen a black capitalist class’ was an integral part of the ‘goal of deracialisation within the context of the property relations characteristic of a capitalist economy.’[21]

What was Mbeki’s understanding of the ‘goal of deracialisation’ of the South African economy and society ‘within the context of the property relations characteristic of a capitalist economy’ he was referring to? This question is of political, economic and ideological importance given the fact that:

‘The negotiations to end apartheid were in the event premised upon the achievement of political equality whilst leaving the structure and functioning of the economy intact. Yet, of course, if white capital was to be untouched how was capitalism in South Africa to be de-racialized, never mind decent living standards achieved for the majority? The transitional compromise removed questions of wealth redistribution from the agenda and confined the settlement to narrowly political and constitutional issues, the establishment of bourgeois order, democratic rights and liberal democratic structures.’[22]

The policy measure whose aim is the primacy of the advancement of material interests of the few over the advancement of the popular socio-economic empowerment structurally serves the strategic interests of the bourgeoisie of advanced capitalist countries in South Africa. It structurally helps to forge and sustain a class alliance between the bourgeoisie of the centre of capitalism and that of South Africa and imperialism in the country. This reality was explained by Sehlare Makgelaneng in 2000 as follows:

‘The task of increasing the camp of African, Asian and Coloured bourgeoisie through ‘black economic empowerment’ programmes will make the South African bourgeoisie more ‘multi-racial’ in composition. It will not be the solution to our economic domination and exploitation by imperialism. It will not even constitute a crucial threat to the dominant position occupied by imperialism in the South African economy. It will help to cement ties between the South African bourgeoisie and the imperialist bourgeoisie. The point is that the advancement of African, Asian and Coloured bourgeoisie is in line with the strategic interests of the South African European bourgeoisie and of imperialism. The advancement of African, Asian and Coloured bourgeoisie will be the advancement of imperialism in its domination and exploitation of the South African economy.’[23]

This position helps us to understand why the dominant fraction of the South African capital with well-entrenched structural interlocking network of interests, interlinkages, exchanges and ties and common patterns of cooperation with international finance capital initiated the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) policy deals for its strategic and tactical interests. According to Kgalema Motlanthe, as the deputy president of South Africa, the BEE policy through which the state has been embarking upon the programme of action in creating and consolidating the black bourgeoisie, was:

‘the brainchild of the mining industry, which deliberately went out to select blacks who could serve as insurance against possible nationalisation. They basically went out in search of blacks who were “connected” and therefore could guarantee some kind of protection. And that is why they had a small pool of people that they could rope into the first BEE deals. And they were debt-funded – the deals were structured such that payment for those shares would have to come off the profit.’[24]

Motlanthe pointed out further that the ‘major beneficiaries’ of the BEE deals ‘were the financial institutions.’[25]

Central to the reality articulated by Motlanthe is the tactical means used by the leaders of the South African mining industry in enriching blacks they selected from ‘a small pool of people’ in advancing their strategic interests. It entailed ‘opportunities and massive enrichment for a relative handful of well-placed individuals’ of ‘debt-funded wealth’ and their ‘advisers’ who became ‘enormously wealthy.’[26] Ann Crotty maintained that this process was not ‘merely the greed of well-placed black individuals’ but also ‘the greed of an army of white financial advisers who realised that BEE deals offered huge opportunities to generate enormous transaction fees.’ Given the strategic importance of the management of the relationship between race and class and the role of state political power in the provision of the economic, financial and trade direction of the South African society since 1994 which included the participation of some blacks as capitalists, one of the crucial important issues to achieve this structural objective was ‘how to provide finance on reasonable terms to the targeted beneficiaries, who generally had limited access to funding.’ This programme of action became ‘huge opportunities’ seized by ‘a team of financial advisers scouring the economic landscape for deals to be done and transaction fees to be earned, largely for their own pockets.’

Crotty explained how ‘a relative handful of well-placed individuals’ or ‘the high-rollers made their millions’ or became millionaires within a short period of time. Cyril Ramaphosa, deputy president of the ANC and South Africa, did ‘score substantially’ after the Molope Group was ‘rescued by Rebhold when he was given substantial mining-related assets, which were used to build up Shanduka.’ The Anglo American Corporation unbundled its Johnnies Industrial Corporation (JCI) when it sold its controlling shares in the JCI or Johnnic to the National Economic Consortium in 1996. This development was a massive opportunity for the BEE deals and its selected beneficiaries. The point is that JCI’s assets included significant shares in the South African Breweries, Premier Food and Times Media. They also included indirectly significant shares in the Mobile Telephone Networks (MTN). The coming to an end of the Johnnic conglomerate led to the consolidation of the MTN. Patrice Motsepe who was excluded from the 1996 Black Economic Consortium made the BEE deal with ‘the enormously wealthy Sacco family, which controlled iron-ore company Assore.’[27] His shares in Assore were central to the development of the African Rainbow Minerals.

Buffers against fundamental change

Some aspects of the criticism of the BEE policy depart from the importance of race in the South African political economy. They are in favour of the white bourgeoisie. Christine Qunta attempted to expose this problem when she maintained in 2011 that the ‘most obvious and rational answer’ to the question raised by some ‘white people’ as to how long Affirmative Action and BEE policies will continue being implemented would be ‘until the economy is controlled by black Africans who constitute the majority’[28] of the South African population. She maintained that the BEE policy was viewed by some whites as ‘a short-term means of controlling even more of the economy and empowering certain well-connected individuals to act as buffers against fundamental change.’

The ‘unspoken agreement’ between some members of the white bourgeoisie and their organic intellectuals and these blacks was ‘we will make you rich overnight and you will not rock the boat by changing the staff and our method of doing business.’[29] The issue of departing from the importance of race in the South African political economy in favour of some white bourgeoisie and petty-bourgeoisie in some aspects of the criticism of the BEE policy can best be understood if we take seriously into account Qunta’s statement: ‘White businesses continue to make enormous profits, often at the expense of their BEE partners’ and that while ‘there is much focus in the media on “tenderpreneurs” and fronting, very rarely are white companies called out for their fraud and dishonesty.’[30] She concluded that the South African economy is run by the decisive minority of the South African population which is ‘2.77 percent’ and ‘yet we expect it to be a competitive growing economy.’ What would be the consequence of this expectation? According to her, what ‘we cannot imagine, however, is that in 15 years we will still have the same highly concentrated, unequal, racialised and underperforming economy of today.’[31]

The reality that some aspects of the criticism of the BEE policy that depart from the importance of race in the South African political economy are in favour of the white bourgeoisie and betty-bourgeoisie is supported by Pallo Jordan in his analysis of the socio-political and economic changes brought into existence by the end of the apartheid rule. This socio-historical development has substantially opened the doors of opportunity to some blacks. One of its consequences is the rapid growth of the African petty-bourgeoisie and bourgeoisie. He maintains that the profile of this relatively wealthy African social forces hides the reality, first, that the end of the apartheid rule has ‘benefited the white minority disproportionately – 87% of whites’ who ‘are now in the upper-income brackets.’ The second reality is ‘the growing disparity between the incomes of the wealthy and the poor, who are overwhelmingly black.’[32]

The fact that some aspects of the criticism of the BEE policy that depart from the importance of race in the South African political economy are in favour of the white bourgeoisie can best be understood if we take into account the reality that before 1994 there was a concentrated focus on the white bourgeoisie. Since 1994 there has been a shift from the focus on the white bourgeoisie to the black bourgeoisie. The focus on the black bourgeoisie excluding the white bourgeoisie is as if or implies incorrectly that the white bourgeoisie in its alliance with imperialism is no longer the central impediment to the long walk to the structural socio-economic change and transformation. It is as if the black bourgeoisie is the key social force within South African capitalism to be defeated by the black working class. Having left out the white bourgeoisie from the requisite criticism, the white working class has been left to white liberal and conservative parties for mobilisation into the defence of the South African capitalism led by the white bourgeoisie in alliance with imperialism. Is it a progressive position to call upon white socialists and communists to play a leading role in mobilising white working class into a progressive and revolutionary movement as an integral part of the struggle to end the benefits of capitalism and racism?

Thabo Mbeki’s about-face

The direction of the BEE policy has been such that some of those who played a leading role in its formulation, adoption and implementation had to criticise some of its consequences. The black bourgeoisie created on the basis of the BEE policy has not, first, contributed towards the support base of the state or the exercise of state political power in South Africa’s internal and external affairs. Second, rather than contributing towards the ‘de-racialisation’ of the South African capitalism, by demonstrating their commitment to have financial, industrial and mining bases within the national economy, BEE beneficiaries have been preoccupied with the accumulation of wealth not the development and progress of the country. It was for these reasons, among others, that in 2006, Mbeki criticised one of the profound consequences of the policy he played a leading role in its formulation, adoption and implementation. In his words:

‘The capitalist market destroys relations of kinship, neighbourhood, profession, and creed [and makes people] atomistic and individualistic. Thus, everyday, and during every hour of our time beyond sleep, the demons embedded in our society, that stalk us at every minute, seem always to beckon each one of us towards a realisable dream and nightmare. With every passing second, they advise, with rhythmic and hypnotic regularity – get rich! get rich! get rich!

‘And thus it has come about that many of us accept that our common natural instinct to escape from poverty is but the other side of the same coin on whose side are written the words - at all costs, get rich in these circumstances, personal wealth, and the public communication of the message that we are people of wealth, becomes, at the same time, the means by which we communicate the message that we are worthy citizens of our community, the very exemplars of what defines the product of a liberated South Africa.

‘This peculiar striving produces the particular result that manifestations of wealth, defined in specific ways, determine the individuality of each one of us who seeks to achieve happiness and self-fulfillment, given the liberty that the revolution of 1994 brought to all of us. In these circumstances, the meaning of freedom has come to be defined not by the seemingly ethereal and therefore intangible gift of liberty, but by the designer labels on the clothes we wear, the cars we drive, the spaciousness of our houses and our yards, the geographic location, the company we keep, and what we do as part of that company.’[33]

This raises the question as to whether Mbeki was not aware that the policy which he played a leading role in its formulation, adoption and implementation was going to lead to the existence of what he is criticising as the former president of the country. The answer to this question is that he was fully aware of the consequences of what he was doing as the Deputy President and the President of South Africa. The point is that the BEE policy formulated, adopted and implemented under the leadership of Mbeki ‘was a deliberate policy.’[34]

Mbeki criticised harshly black capitalists in 1978. In his paper, The Historical Injustice,[35] presented at a seminar in Ottawa, Canada, in 1978 and published in Sechaba in March 1979, he pointed out that ‘black capitalism instead of being an antithesis is rather a confirmation of parasitism with no redeeming features whatsoever, without any extenuating circumstances to excuse its existence.’[36] In criticising this deliberate policy, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela maintained in 2010 that it was ‘a joke.’ In her words:

‘Black economic empowerment is a joke. It was a white confidence measure made up by local white capitalists. They took malleable blacks and made them partners. But those who had struggled and had given blood were left with nothing. They are still in shacks: no electricity, no sanitation and no sign of an education.’[37]

The ANC through its political administration of the South African society since 1994 has not been able to seriously change the national socio-economic direction in the interest of the majority of the people. The end of the apartheid rule has helped to substantially increase South Africa’s integration into global capitalism. Characterised, among others, by a small minority of blacks being bourgeoisie and petty-bourgeoisie, it has led, firstly, to a limited reduction of the socio-economic division between blacks and whites and, secondly, to an increase in the division between the rich and the poor.

One of the consequences of these forms of division has been the structural failure to achieve a substantial progress towards a meaningful socio-economic empowerment or justice or to move decisively against the foundation of the structure and the operational framework of the political economy of the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism in the country. John S. Saul regards this socio-historical development as ‘recolonisation’ of South Africa by finance capital.[38]

Saul’s statement points to the structural definition of the post-apartheid South Africa being a neo-colonial social formation in its relation with the international financial capital. There are some scholars who maintain that the domination of the South African economy by finance capital has increased following the end of the apartheid rule and that this is reflected in the direction of its economic policy. Sam Ashman, Ben Fine and Susan Newman maintain that ‘financial interests have influenced policy and affected class formation’ and that ‘many commodity markets have become increasingly financialized, with speculation affecting their volatility (not least food and energy).’[39] The domination of the South African economy by the white national bourgeoisie is relative in relation to that exercised by the financial oligarchy of the advanced capitalist countries. Directly related to this reality is the fact that the domination of South Africa by imperialism has survived the end of the apartheid rule.

The reality that the structure and operational framework of the economy has remained essentially the same since 1994 is articulated by Njabulo Ndebele when points out that:

‘It seems that instead of setting out to create a new reality, we worked merely to inherit an old one … Redistribution was given priority over creation and invention. We reaffirmed the structures of inequality by seeking to work within the inherent logic (and) the promise of human revolution once dreamed of was conceptually subverted.’[40]

Post-apartheid power relations

Analysing old apartheid social power relations as they meet the post-apartheid South Africa, Gunnett Kaaf maintains that ‘in many respects old power relations formed under apartheid, in the economic production systems’ have ‘remained almost the same.’[41] His conclusion is that the ‘big monopolies in the mining, energy and finance industries’ have ‘remained in charge, continuing to wield social power’ and that they have ‘co-opted, as junior partners, the black business class and the black political elites to lend legitimacy.’[42] The assumption and exercise of political power by some blacks has not seriously and negatively affected economic power and authority exercised by some whites. Kaaf’s view of social power relations challenges the position that the 1994 political dispensation has led to the separation between political power and economic power. According to him:

‘Because of the centrality of wealth and economic power in capitalist societies, those who have wealth and economic power wield political power, even if they are not in political life – and they wield even more social power.’[43]

Through the BEE policy initiatives, South African capitalists dominant in the mining, energy and finance sectors of the economy ensure that they are structurally represented within the state for economic policy to advance their strategic interests. According to Moeletsi Mbeki, the objective of these empowerment initiatives was to ‘wean the ANC from radical economic ambitions, such as nationalising the major elements of the South African economy’ and to provide themselves with ‘a seat at the high table of the ANC government’s economic policy formulation system.’[44]

The few black capitalists depend economically, financially and ideologically also on white South African capitalists and imperialism. Its advancement is limited by its being the beneficiary of the reallocation of rights, particularly in the mining sector of the South African economy. Black capital has not yet articulated a clear, coherent and strong ideological commitment to capitalism. It is not active in the strategic manufacturing and agricultural sectors of the South African economy. Despite the strategic importance of the land reform in the South African political economy and unequal control, ownership and distribution along racial lines and the consequent structural need for their transformation, the new black capitalists are not practically active in terms of engagement in land. They are also not theoretically active in terms of being vocal in demanding the transformation of control, ownership and distribution of land. They are also not vocal in ensuring that the South African state political power and authority and public capital are used in directing South Africa’s external economic and trade interests in conjunction with foreign policy in their interests. Their ownership of companies controlling South African leading newspapers has no impact on their content particularly regarding their view of black South Africans, South Africa’s role in Africa and beyond and South Africa’s relationship with Africa, the South, the North and the rest of the world.

Briefly, they are not active in the productive activities of the South African political economy and social life including on matters relating to black South Africans. Their call for change and transformation is essentially their demand that they should be more and more included in the task to widen the boundaries of privileges. The transformation process incorrectly viewed as the task to widen the boundaries of privilege has so far helped to protect and entrench the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism in the country.

Motlanthe provides some of the key characteristic features of the members of the black capitalists created and sustained on the basis of the BEE policy. According to him:

‘they don’t have an impact among the blacks, as it were. Their impact is minimal. It’s why they channel their support, to curry favour directly from the ANC. In a sense, if we are brutally frank, they’re rent-seekers who extend that role to the ANC as an organisation and therefore are very central in corrupting the ANC, as it were. And so, for them to be described as part of the motive forces can only mean that they will vote for the ANC. That’s all. But they are not a factor, as I said. You can’t rely on them to play a meaningful role, for example, in discussion on transformation of the economy. They have no ideas. They have no brainpower, are not engaged in research. They are not a factor, as I see them. Instead, I think, they have been included in an already existing business class, which determines the voice of that business class and the views of that business class are determined by a different set of people.’[45]

Ashman, Fine and Newman provide a critical analysis of the key factors characterising members of the black capitalists created and sustained on the basis of the BEE policy. On the creation and integration of the black bourgeoisie or ‘the formation or incorporation of a small black elite,’ they maintain that this social class among blacks is ‘both highly financialized and often highly dependent upon the state’ and that its ‘enrichment is notable for involving neither land (other than reallocated mineral rights as opposed to agriculture) nor, in general, productive activity.’[46]

Black companies encounter profound problems in entering some sectors of the economy except through acquisition. The significant exceptions are sectors such as mobile telecommunications, media, information technology and healthcare.[47] BEE as an integral part of the economic policy is limited, among others, given the fact that many of its beneficiaries are whites. Its privatisation component as a means of creating and consolidating the black bourgeoisie is limited. Significant BEE deals have links with international finance capital. Its profound limitation is the fact that it ‘does not create a productive class within South Africa.’[48]

Ashman, Fine and Newman point to the crucial decline in the qualitative movement towards socio-political and economic change and transformation in the post-apartheid South Africa. This can best be understood if we come to grips with the reality that one of the key characteristic features of the relationship between the race question and the class question in the post-apartheid South Africa is the ‘incorporation of erstwhile progressives through enrichment once in power.’ The formation of ‘a black elite’ or bourgeoisie and petty-bourgeoisie, ‘often out of trade union leaders and political activists, has been a decisive part of the process and has entailed significant intellectual and political retreats and is sickeningly depressing.’[49] Why is this development ‘sickeningly depressing?’ The point is that:

‘It has been matched by an equally significant expansion of black employment, opportunities and advancement of for at most a minority, primarily through the state, with a corresponding and understandable shifting balance of trade union activity to further material interests as opposed to more fundamental transformative goals, as decline is experienced across the more traditional sources of militancy and organization across mining and large-scale industry.

‘In the case of South Africa, the intensive globalization and financialization of the economy has involved the corporate restructuring that has enabled incorporation of black elite. Here the form of enrichment is notable for its lack of productive activity. The black elite’s incentives to engage in and promote policies for economic and social investments are reduced to the minimalist imperatives of social, political and ideological containment.’[50]

The benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism in South Africa are in the form of mass poverty for the majority of its people and wealth and privileges for its decisive minority which includes few blacks. One of the profound contradictions of the post-apartheid South Africa is that wealth and privileges of the beneficiaries of apartheid have been protected through the end of the apartheid rule. The fact that the end of the apartheid rule has so far been structurally protecting the wealth and privileges of the beneficiaries of the apartheid rule raises the fundamental question as to how the post-apartheid state can effectively de-racialise capitalism and make qualitative achievement in the material conditions of the majority of the South African people without at the same time embarking upon a programme of action which negatively affect those who have been benefiting more than the decisive majority of the population from its economic policy.

Conclusion

This work has provided a critical analysis of the relationship the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism as an integral socio-economic part of the South African history. This task was executed by highlighting the importance of the relationship between race and class in South Africa before and since 1994. It provided analysis of the relationship between the Black Economic Empowerment policy and the perpetuation of the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism.

It recommends that the relationship between race and class should be dialectically and organically weaved without departing from the importance of the racial factor in the South African politics of the structural socio-economic change. Its theoretical and practical importance is that the resolution of the benefits and misfortunes of capitalism and racism is in essence the resolution of the South African national question.

* Dr Sehlare Makgetlanenng, a rated researcher in African affairs by the National Research Foundation and political scientist and political economist based in Pretoria, South Africa, can be contacted at [email protected]. This essay is a compressed version of a journal article, ‘How capitalism and racism continue to shape the socioeconomic structure of South Africa’, published in Africanus: Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 46, Issue 1, 2016.

References

[1] Thabo Mbeki, “Domestic and Foreign Policies of a New South Africa,” Review of African Political Economy, No 11, January-April 1978, p. 7.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Karl Marx, quoted in Thabo Mbeki, “Domestic and Foreign Policies of a New South Africa,” Review of African Political Economy, No 11, January-April 1978, p. 7.

[4] Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (New York: Bantam Dell, 2003), p. 793.

[5] Ibid., pp. 793-4.

[6] Ibid., p. 794.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., p. 563.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party, in Marx, Engels and Lenin on Historical Materialism (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1984), p. 85.

[11] Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A New History of Global Capitalism (London: Penguin Books, 2014), pp.ix-82.

[12] Dani Wadada Nabudere, The Crash of International Finance Capital and its Implications for the Third World (Harare: SAPES Trust, 1989), p. 125.

[13] Ngugi wa Thiongo, “Recovering our memory: South Africa in the Black Imagination,” in Steve Biko Foundation, the Steve Biko Memorial Lectures, 2000-2008 (Johannesburg: Steve Biko Foundation and Pan Macmillan South Africa, 2009), p. 55.

[14] Ibid., p. 56.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] African National Congress, Strategy and Tactics of the African National Congress, in Ben Turok (editor), Revolutionary Thought in the 20th Century (London: Zed Press, 1980), pp. 155-56.

[18] Joe Slovo, “South Africa – No Middle Road,” in Basil Davidson, David Wilkinson and Joe Slovo (editors), Southern Africa: The New Politics of Revolution (Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1996), p. 141.

[19] Thabo Mbeki, quoted in Baffour Ankomah, “The meaning of freedom,” New African, Issue 520, August/September 2012, p. 11.

[20] Thabo Mbeki, Challenge of the formation of a black capitalist class: Speech at the Annual Conference of the Black Management Forum, Kempton Park, Gauteng, November 20, 1999.

[21] Mbeki, quoted in Ankomah, “The meaning of freedom,” p. 11.

[22] Sam Ashman, Ben Fine and Susan Newman, “The Crisis in South Africa: Neoliberalism, Financialization and Uneven and Combined Development,” in Leo Panitch, Greg Albo and Vivek Chibber (editors), Socialist Register 2011: The Crisis This Time (London: The Merlin Press, New York: Monthly Review Press and Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2010), p. 182.

[23] Sehlare Makgetlaneng, “Key issues in the South African economic transformation process,” Politeia: Journal of the Department of Political Sciences and Public Administration, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2000, p. 40.

[24] Kgalema Motlanthe, The Role of Emerging Black Business: An Interview with Kgalema Motlanthe by Ben Turok, New Agenda: South African Journal of Social and Economic Policy, Issue 53, First Quarter 2014, p. 18.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ann Crotty, “BEE deals with a skimmer’s dream come true,” Sunday Times (Johannesburg), 27 April 2014, p. 3.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Christine Qunta, “BEE will end only when black Africans control the economy,” Pretoria News (Pretoria), 26 April 2011, p. 6.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Z. Pallo Jordan, “Historic ironies litter our 20 years of freedom,” Business Day (Johannesburg), 28 November 2013, p. 13.

[33] Mbeki, quoted in Ankomah, “The meaning of freedom,” p. 11.

[34] Ben Turok, The Role of Emerging Black Business: An Interview with Kgalema Motlanthe by Ben Turok, New Agenda: South African Journal of Social and Economic Policy, Issue 53, First Quarter 2014, p. 18.

[35] This paper, The Historical Injustice, is the same paper, Domestic and Foreign Policies of a New South Africa, by Thabo Mbeki published in Review of African Political Economy, No 11, January-April 1978.

[36] Thabo Mbeki, quoted in Mcebisi Ndletyana, “Policy incoherence: A function of ideological contestations?” in Udesh Pillay, Gerald Hagg and Francis Nyamnjoh (editors), State of the Nation South Africa 2012-2013: Addressing inequality and poverty (Cape Town: HRSC Press, 2013), p. 64

[37] Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, quoted in Francis Nyamnjoh, “Freedom Day on SAfm: Introducing the South African society,” in Udesh Pillay, Gerald Hagg and Francis Nyamnjoh (editors), State of the Nation South Africa 2012-2013: Addressing inequality and poverty (Cape Town: HRSC Press, 2013), p. 310.

[38] John S. Saul, “On taming a revolution: the South African case,” in Leo Panitch, Greg Albo and Vivek Chibber (editors), Socialist Register 2013: The Question of Strategy (London: The Merlin Press, New York: Monthly Review Press, 2012), p. 212.

[39] Ashman, Fine and Newman, “The crisis in South Africa: neoliberalism, financialization and uneven and combined development,” in Panitch, Albo and Chibber (editors), Socialist Register 2011: The Crisis This Time, p. 175.

[40] Njabulo Ndebele, quoted in Harry Boyte and Peter Vale, “Lessons from 1955 on how to reimagine the nation,” Business Day (Johannesburg), 20 September 2013, p. 11.

[41] Gunnett Kaaf, “Marikana: Old Apartheid Social Power Relations meet Democratic South Africa,” Amandla! South Africa’s new progressive magazine standing for social justice, Issue No. 35, August-September 2014, p. 32.

[42] Ibid., pp. 32-3.

[43] Ibid., p. 33.

[44] Moeletsi Mbeki, Architects of Poverty: Why African Capitalism Needs Changing (Johannesburg: Picador, 2009), p. 68.

[45] Motlanthe, The Role of Emerging Black Business: An Interview with Kgalema Motlanthe by Ben Turok, p. 19.

[46] Ashman, Fine and Newman, “The crisis in South Africa: neoliberalism, financialization and uneven and combined development,” in Panitch, Albo and Chibber (editors), Socialist Register 2011: The Crisis This Time, p. 187.

[47] Ibid., pp. 187-8.

[48] Ibid., p. 188.

[49] Ibid., p. 191.

[50] Ibid.

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to [email=[email protected]]editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org[/email] or comment online at Pambazuka News.