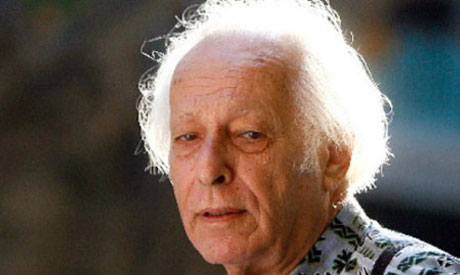

Samir Amin: a vital challenge to dispossession

The author looks at the theories of one of Africa’s greatest radical thinkers.

Samir Amin (1931-2018) was one of the world’s greatest radical thinkers – a “creative Marxist” who went from Communist activism in Nasser’s Egypt, to advising African socialist leaders like Julius Nyerere to being a leading figure in the World Social Forum.

Samir Amin’s ideas were formed in the heady ferment of 1950s and ’60s, when pan-Africanists like Kwame Nkrumah ran Ghana and Julius Nyerere Tanzania, when General Gamal Abdel Nasser was transforming the Middle East from Amin’s native Egypt and liberation movements thrived from South Africa to Algeria.

Africa looked very different before the International Monetary Fund destroyed what progress had been made towards emancipation and LiveAid created a popular conception of a continent of famine and fecklessness. Yet through these times, Amin’s ideas have continued to shine out, denouncing the inhumanity of contemporary capitalism and empire, but also harshly critiquing movements from political Islam to Eurocentric Marxism and its marginalisation of the truly dispossessed.

Global power

Amin believed that the world capitalism – a rule of oligopolies based in the rich world – maintains its rule through five monopolies – control of technology, access to natural resources, finance, global media, and the means of mass destruction. Only by overturning these monopolies can real progress be made.

This raises particular challenges for those of us who are activists in the North because any change we promote must challenge the privileges of the North vis-à-vis the South. Our internationalism cannot be expressed through a type of humanitarian approach to the global South – that countries in the South need our “help to develop”. For Amin, any form of international work must be based on an explicitly anti-imperialist perspective. Anything else will fail to challenge structure of power – those monopolies which really keep the powerful powerful.

Along with colleagues like André Gunder Frank, Amin see the world divided into the “centre” and the “peripheries”. The role of peripheries, those countries we call the global South, is to supply the centres – specifically the “Triad” of North America, Western Europe and Japan – with the means of developing without being able to develop themselves. Most obviously, the exploitation of Africa’s minerals on terms of trade starkly favourable to the centre will never allow African liberation, only continual exploitation.

This flies in the face of so much “development thinking”, which would have you believe that Africa’s problems come from not being properly integrated into the global economy which has grown up over the last 40 years. Amin believes in fact Africa’s problem stem from it being too integrated but in “the wrong way”.

In fact, as long as the monopolies of control are intact, countries of the centre have had few problems globalising production since the 1970s. Sweatshop labour now takes place across the periphery but it hasn’t challenged the power of those in the North because of their control of finance, natural resources, the military and so on. In fact, it has enhanced their power by reducing wages and destroying a manufacturing sector that had become a power base for unionised workers.

So there is no point whatever in asking countries of the centre to concede better trading relationships to the peripheries. Amin is also concerned at environmental activism, which too often becomes a debate about how countries of the centre manage their control of the world’s resources, rather than challenging that control. It is vital that Northern activists challenge the means through which the ruling class in their own society exerts control over the rest of the world.

De-linking

Of course, this is not just a project for activists in the North – far from it. The theory for which Amin is most famous that of “de-linking”.

De-linking means countries of the periphery withdrawing from their exploitative integration in the global economy. In a sense it is de-globalisation, but it is not a form of economic isolation – something which African socialist leaders too readily fell into. Rather it means not engaging in economic relationships from a point of weakness.

Amin argues that Southern countries should develop their economy through various forms of state intervention, control of money flowing in an out of their financial sectors and promoting trading with other Southern countries. Countries must nationalise financial sectors, strongly regulate natural resources, “de-link” internal prices from the world market, and free themselves from control by international institutions like the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Whatever problems come with nationalised industries, it is the only possible basis for a genuinely socially controlled economy going forward.

After 30 years of being told that their problems would be solved by exporting more, privatising their natural resources and liberalising their financial sectors, many developing countries would today do well to heed Amin’s advice. Instead, too many countries have bought into a de-politicised narrative which posits ideologically loaded terms like “good governance”, “poverty” and “civil society” carefully disguising questions as to how poverty happened, what interests governance serves, or the legitimacy of organisations claiming to speak on behalf of the dispossessed.

Amin did not believe that the “rise” of China, India and other emerging economies has in any way broken the power of the oligopolies, in fact that power has only become more concentrated. But there have been important changes. Imperialist powers have realised competition between themselves is not helpful and have created a sort of collective imperialism which is expressed through institutions like the WTO and the International Monetary Fund.

Capitalism, “a parenthesis in history”

Capitalism is experiencing a profound long-term crisis to which Amin believes it has no solution short of political barbarism. He describes this form of capitalism as “senile”.

This crisis is characterised by an increased dependence on finance, which means less and less money is being made from productive activities, and more from simple “rent”. It is a far more direct means of stealing wealth from the majority of the world. The accompanying form of politics means that democracy has been reduced to a farce in which people are spectators in an elite drama – that is when they are not fulfilling their proper role of consuming.

Capitalism necessarily requires an on-going process of dispossession so that it can accumulate and continue to expand. Capitalism could not have developed without the European conquest of the world – the availability so many “spare” resources was vital. The safety value for many of those dispossessed from European land was the “new world”, which allowed mass emigration – though of course others died in droves, witness the Irish Potato Famine.

So as much as many of the dispossessed might aspire to the lives of those in advanced capitalist countries, it is simply not possible. Nor can traditional Marxists be correct when they say capitalism is a necessary stage on the path to socialism – a view that Amin describes as “Eurocentric”.

Industry cannot incorporate more than a small fraction of humanity, but it does require the resources that that humanity depends upon. So the only way that capitalism can move forward is through the creation of a “slum planet” – a sort of “apartheid at the world level”. Amin sees the dispossession of the peasantry across the peripheral countries will become the central issue of the 21st century.

This is one reason why Amin see the role of the peasantry in the South – almost half of humanity after all – as key to determining the future. The strength of movements around food sovereignty, against land grabbing and supporting the rights of indigenous peoples, give support to this theory. But for Amin, agriculture is not merely a big opportunity; the existence of the peasantry presents capitalism with an insurmountable challenge.

Amin believes the road to socialism depends on reversing this trend of dispossession meaning, at national and regional levels, protecting local agricultural production, ensuring countries’ have food sovereignty and de-linking internal prices from world commodity markets. This would stop the dispossession of peasants and their exodus into the towns.

Only this revolution in the way the land is seen, treated and access can lay the basis for a new society. This also means ditching the idea of “growth” as it is spoken about today and by which all world economies are judged, which really benefits only a minority of the world population. The rest of humanity is “abandoned to stagnation, if not pauperisation”.

The long road to socialism

Perhaps this makes Samir Amin sounds rather idealistic in his approach, but this is far from true. Amin explicitly rejects the idea of a “24 hour revolution” – a single insurrectionary act that ushers in a period of socialism. Indeed he accepts there may well be a need to use private, even international capital, in order to diversify Southern economies. The important thing is control. For this reason Amin also refuses to use the phrase “socialism of the 21st century” focussing on the need for “the long route of the transition to socialism”.

But that is not to say there have not been significant victories. Interestingly, Amin is less interested in developments in Latin America, which he believes contain risks of repeating the mistakes of many national liberation movements on the 1950s and 60s in becoming a form of “popular statism”. Amin is more interested in Nepal as a possible future model to look towards. He also sees the Chinese revolution as an incredibly significant event in directly challenging the basis of capitalism and in the struggle for democratic socialism, most especially in its “abolition of the private property of land” and the formation of powerful communes and collectives.

Amin’s somewhat romantic view of the Chinese revolution is certainly challenging to Western sensibilities, but his underlying view that the formation of democracy must go beyond a narrow political project, and that peasants – and especially women – through collective organisations, might be better placed than Western individualists to define a really progressive vision of democracy needs to be properly taken on board by activists.

Enlightenment

Perhaps Amin’s central thesis is somewhat obvious, but it is often forgotten – that a true revolution must be based on those who are being dispossessed and impoverished. But he goes further in undermining the assumption that any thinking emerging from the South will lack enlightenment, or that a lack of enlightenment should be excused.

He believes the Enlightenment was humanity’s first step towards democracy, liberating us from the idea that God created our activity. He has caused controversy in his utter rejection of political Islam. This ideology, embedded for example in Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, obscures the real nature of society, including by playing into the idea that the world consists of different cultural groups which conflict with each other, an idea which helps the centre control the peripheries.

Amin’s view is that organisations like the Muslim Brotherhood, with their cultural and economic conservatism, are actually viewed positively by the United States and other imperialist governments. And he doesn’t limit his critique to Islam either, launching similar criticism on political Hinduism practiced by the Bharatiya Janata Party in India and Political Buddhism, expressed through the Dalai Lama.

Creative Marxism

Samir Amin describes himself as a “creative Marxist” – “to begin from Marx but not to end with him or with Lenin or Mao” – which incorporates all manner of critical ways of thinking even ones “which were wrongly considered to be “alien” by the dogmas of the historical Marxism of the past.”

These views are surely more relevant today than when Amin started writing. A creative Marxism takes proper account of the perspective and aspirations of the truly dispossessed in the world, break out of historical dogmas and rejects attempts to stick together a broken model, but equally sees the impossibility of overthrowing this model tomorrow.

* Nick Dearden is Director of United Kingdom campaigning organisation Global Justice Now. He was previously the director of Jubilee Debt Campaign.