African Continental Free Trade Area: Prospects and problems for implementation

The majority of Africa Union member states, 44 out of 55, have signed a free trade agreement whose aim is to create a single African market of economic cooperation thus creating the biggest economic zone in the world.

On the eve of the 55th anniversary of the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), the predecessor of the African Union (AU), a large bloc of nation-states have signed a document entitled “Agreement Establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area” (AfCFTA) in Kigali, Rwanda on 20-21 March 2018.

Some 44 governments out of the 55 member states of the AU attended the conference chaired by Rwandan President Paul Kagame.

The AfCFTA has theoretically gone into effect with the ratification of the protocols by 22 AU governments. Other states are evaluating the agreement in order to bring it into line with their own internal legal and economic situations.

If the framework is ratified by all African nations, the AfCFTA will represent one of the largest economic zones globally. Altogether there will be 1.2 billion people covered by the agreement within 55 governments, which are estimated to already encompass US $4 trillion in investment and consumer spending.

When the OAU was founded in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia on 25 May 1963, there were sharp differences over the political character and historical trajectory of continental unification. Progressive and revolutionary states such as the Republics of Ghana, Guinea, Algeria, Mali, Egypt and others wanted a more rapid pace leading to the formation of a United States of Africa. More moderate and conservative governments advocated for a gradualist and regional approach, which would not threaten ties with former colonial and imperialist states and their institutions.

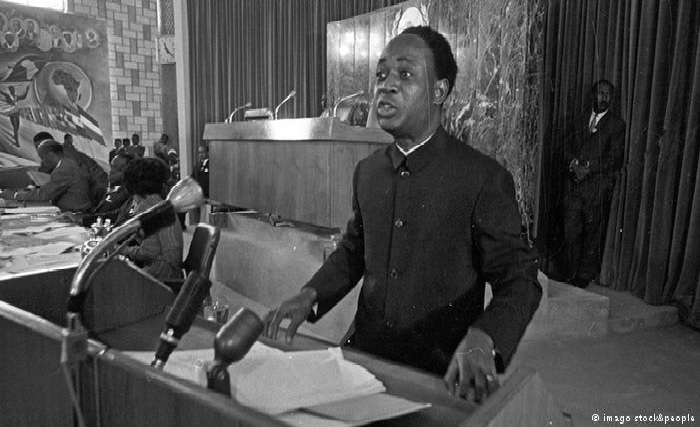

By October 1965, at an OAU summit in Accra, Ghana, President Kwame Nkrumah made a last ditch appeal to African states to immediately unite in order to stave off the entrenchment of neo-colonialism and to accelerate the elimination of white minority rule in non-liberated areas. Nkrumah was later removed from office just four months later in February 1966. His critique of the world capitalist system published for the OAU Summit in Accra entitled, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, infuriated the United States administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson which engineered the coup through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the State Department utilising lower-ranking military officers and the police.

When discussions were held in 1999 in Sirte, Libya under the-then leadership of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, it was recognised by many that the unification process must take a qualitative leap towards creating a single currency, trading area and continental military force. The AU was officially established in 2002 in Durban, South Africa under the reign of President Thabo Mbeki. Nevertheless, the Gaddafi government was destroyed nine years later (2011) at the aegis of the same imperialist forces, which had undermined Ghana in 1966.

With specific regard to the AfCFTA, one writer Landry Signe says, “It creates a single continental market for goods and services as well as a customs union with free movement of capital and business travellers. The African Union agreed in January 2012 to develop the AfCFTA. It took eight rounds of negotiations, beginning in 2015 and lasting until December 2017, to reach agreement…. One of its central goals is to boost African economies by harmonising trade liberalisation across sub-regions and at the continental level. As a part of the AfCFTA, countries have committed to remove tariffs on 90 percent of goods. According to the United Nations Economic Commission on Africa, intra-African trade is likely to increase by 52.3 percent under the AfCFTA and will double upon the further removal of non-tariff barriers.”[[i]]

This concept of enhancing inter-African trade is essential in any project designed to build sustainable growth and genuine development. The legacies of the Atlantic Slave Trade and classical colonialism directed African resources and labour power out of the continent to Europe and North America.

The same article then goes on to note, “The AU hopes to create a single common market embracing all countries in Africa. However, only 44 countries have signed the AfCFTA’s establishing framework to date. And just 30 nations have signed the Free Movement Protocol — signifying the free movement of people, right of residence and right of establishment…. The final critical steps for the AU will be to persuade the remaining countries to join, to create a secretariat to coordinate the implementation and to provide enough resources to ensure the AfCFTA’s success.”

Problems facing the AfCFTA

Two important states, which have not ratified the agreement are the Republics of Nigeria and South Africa, two of the largest economies and population groups on the continent. Of the two, the current government led by President Muhammadu Buhari seems the most hesitant to throw their weight behind the AfCFTA. The Nigerian head of state did not attend the gathering in Kigali due to internal pressures.

Reports indicate that there was strong objection to signing the accord from both the Manufacturing Association of Nigeria and the Nigerian Labour Council where the two class camps were concerned that certain measures within AfCFTA would undermine local industries and bring about job losses. The Labour opposition believes that the reduction of trade tariffs by 90 percent would result in a large influx of consumer goods that could undermine local markets.

Also Nigeria wants to involve other industries in the national economy including agricultural producers in the rice and poultry sectors along with the Governors’ Forum. Other key elements to be involved in further consultations are the National Association of Chambers of Commerce, Industry, Mines and Agriculture; Federal Inland Revenue Service; Nigeria Ports Authority; Nigeria Customs Service and Nigeria Immigration Service.

South Africa has indicated as well that there needs to be more negotiations and evaluations by national interests. President Cyril Ramaphosa did attend the conference and pledged support in principal for the idea of a free trade zone in Africa.

Nevertheless, Ramaphosa emphasised in Rwanda, “All that holds us back from signing the actual agreement is our own consultation process. We still need to consult at home, to consult in Cabinet, to consult our various partners at Nedlac [the body comprising government, business, labour and community organisations], but also to finally consult our parliamentarians, so we are really just going through what you would call the ‘clean-up process’.”[[ii]]

More formidable impediments to the realisation of AfCFTA

Moreover, the real structural barriers to the implementation of such a trade agreement on the continent have more to do with imperatives of overcoming the dominance of international finance capital, which still determines the exigencies of actual global value and exchange. There has been much written on the phenomenal growth in Africa during the first decade of the 21st century.

Yet with the decline of commodity prices in recent years, a considerable amount of this process of growth largely stemming from Foreign Direct Investment has swiftly eroded. The overproduction of oil and other energy resources initiated by the US has taken its toll on the emerging economies. South Africa and Nigeria are said to be only barely recovering from recessions and other states such as Mozambique are being compelled to renegotiate the terms of its loans and bond issues.

All of this is occurring while huge findings of oil, natural gas and strategic minerals are underway all along the east coast of Africa. Within the Southern Africa region a treasure trove of additional mineral wealth is now known to exist.

What are the implications for these structural barriers to the realisation of a workable free trade area for the AU member states? How can the AfCFTA benefit the long-term interests of workers, farmers and youth through the raising of their incomes, living standards and educational levels?

Nkrumah pointed out in his writings surrounding the founding of the OAU in 1963 that the genesis of unification was not necessarily dependent upon a uniformity of social and economic systems. However, the consolidation of the objectives of Pan-Africanism is contingent upon the adoption of Socialist methods of planning and reorganisation.

In an address to the Ghanaian Parliament on 21 June 1963 seeking the ratification of the OAU Charter of 1963, Nkrumah reiterates, “The social organisations in our New Africa must embrace all sections of our people. The goals of our endeavours have always been to secure the material basis for increasing the economic and social wealth of our farmers, peasants and workers. Our revolution, therefore, must be identified with the organisations of the workers and our peasant population. We cannot succeed very much in our aims, if there should be conflict between the trade unions as the organisation of the workers and our national governments, which are also serving the same interests. Our identical aims must make it possible for us to harmonise relations and work within a coordinated programme for solving the problems that face Africa.

The All-African Trade Union Federation (AATUF) must therefore be in a position to mobilise the exploited masses of Africa for the final onslaught in the battle against imperialism and neo-colonialism. In the independent states of Africa, AATUF has a vital role to play in evolving a trade union orientation which will enable the workers to play their full part in socialist construction.”[[iii]]

Therefore, the only viable option for a unified Africa is the movement towards Socialism. This orientation would preclude the military and intelligence intervention within AU member states where today the advent of the United States Africa Command is encroaching under the guise of a “war against terrorism.”

Already much trepidation exists in states such as Ghana where the current conservative regime has enhanced its military relationship with Washington under the presidency of Donald Trump and all of which this implies. The best way to fight “terrorism” and imperialist militarism is to build an integrated All-African Union Government encompassing a uniform monetary system, industrial consolidation and a combined defence and peacekeeping force with the independent capacity to guard continental interests.

*Abayomi Azikiwe is Editor at Pan-African News Wire

[i] The Washington Post, 29 March 2018

[ii] City Press, 27 March 2018

[iii] http://www.nkrumahinfobank.org/article.php?id=521&c=46 accessed on 16 April 2018