Rebellion and revolution from 1968 to 2018

This article is an edited transcription of an address that Abayomi Azikiwe delivered at the Annual Detroit African American History Month Forum held on 24 February 2018. The gathering was chaired by Kelley Carmichael of Workers World Party Detroit branch.

23 February 2018 represented the 150th birthday of W.E.B. Du Bois, one of the leading intellectual and organisational figures to emerge during the 19th century who extended his contributions well into the 20th century. Du Bois was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, United States of America in 1868, only three years after the conclusion of the Civil War.

Du Bois and his wife, Shirley Graham Du Bois, were invited to Ghana to play a leading role in the process of building Pan-Africanism and Socialism. Du Bois was appointed as the Director of the Secretariat for the Encyclopaedia Africana.

His years spanning from the first decade of the 20th century through World War II were filled with various accomplishments including the participation in what is considered the First Pan-African Conference in London, United Kingdom during 1900; the co-founding of the Niagara Movement in 1905 eventually leading to the beginning of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) in 1909.

In 1910, Du Bois founded Crisis Magazine where he would serve as its editor until 1934. He was the convener of the Pan-African Congresses held in 1919, 1921, and 1923 in Western Europe and then the Fourth of such gatherings in New York City in 1927, where African American women such as Addie B. Hunton would provide organisational and financial support, which in essence saved the movement despite the doubts harboured by Du Bois himself.

Du Bois would influence countless numbers of African American scholars and activists during this period. One of which was Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950) of Virginia, who would go on to make his pioneering contributions related to the documentation and popularisation of African and African American history.

Woodson founded the Association for the Study of Negro (African American) Life and History in 1915. The following year he initiated the Journal of Negro History. Then in 1926, he launched Negro History Week in February. This would eventually be extended to Black History Month in 1976, winning recognition from the federal government.

There were notions that the confederacy was largely concerned about “state’s rights” and that the reconstruction period was discredited by the promotion of “incompetent and corrupt” Black politicians.

Such a method of thinking rationalises the founding of the Ku Klux Klan in 1866 in Tennessee as a mechanism utilised to restore the honour of the southern planters and to protect the “sanctity of white womanhood, etc.” Segregation, commonly known as Jim Crow, was necessary to restrain the African American people and was believed to be “beneficial” for both races.

Liberation and social transformation of 1968

In 1967, rebellions struck over 160 cities throughout the US and Black Nationalist hate groups utilised destabilisation programmes under the direction of J. Edgar Hoover. At this time President Johnson, through his Attorney General Ramsey Clarke, approved hard-hitting measures to disrupt, misdirect, discredit and otherwise neutralise the African American liberation movement in the US.

Martin Luther King’s response was to build a Poor People’s Campaign (PPC). The project was announced in late 1967 and work immediately began aimed at mobilising thousands from across the US to come to Washington, DC in the spring of 1968. People would occupy areas in close proximity to the White House demanding immediate policy measures to achieve full employment, a guaranteed annual income and the implementation of national health insurance. The programme of the PPC called for the investment of billions within the central cities and rural areas devastated by poverty and social neglect.

In a statement during May 1967, King said: “I think it is necessary for us to realise that we have moved from the era of civil rights to the era of human rights…When we see that there must be a radical redistribution of economic and political power, then we see that for the last 12 years we have been in a reform movement…That the Voting Rights Bill, we moved into a new era, which must be an era of revolution…In short, we have moved into an era where we are called upon to raise certain basic questions about the whole society.” (Poor People Campaign, no date)

This did not work in the 1960s when the capitalist system was much stronger than in the second decade of the 21st century. It clearly will not be successful in this period when the ruling class is demanding even more on the productive capacity and surplus deriving from the labour of the working masses.

Our situation in Detroit is symptomatic of the current crises impacting the cities. This city [Detroit] has been run by Democrats for decades yet they continue to accept the Republican policies of “trickle-down economics.” We have the phenomenon of local tax captures, theft of state revenue sharing monies, the redirecting of federal funds designed to assist the people being used against them, and the eradication of any semblance of bourgeois democratic rights for the people.

Memphis workers’ strike and assassination of King

In 1733, 1,300 African American men, seeking recognition through the American Federation of State, Municipal and Country Employees (AFSMCE), launched the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike.

On 1 February 1968, two workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed to death by a defective garbage truck. Workers had been complaining for years about the hazardous conditions under which they toiled on a daily basis. The city administration took no concrete actions to improve safety on the job and the deaths of these workers served to inflame tensions and embolden the workers.

No real benefits were allocated to the families of Cole and Walker. The workers held a meeting on 11 February calling for a work stoppage until recognition was granted. Mayor Henry Loeb, a businessman turned politician who had just taken office, refused to negotiate with the sanitation workers and their union leaders. Loeb even declared that it was illegal for public service workers to strike in Memphis.

Nonetheless, the workers walked off the job paralysing the city’s garbage collection process leaving mountains of refuge in the streets. The Memphis City Council made attempts to end the strike, which proved unacceptable to the workers.

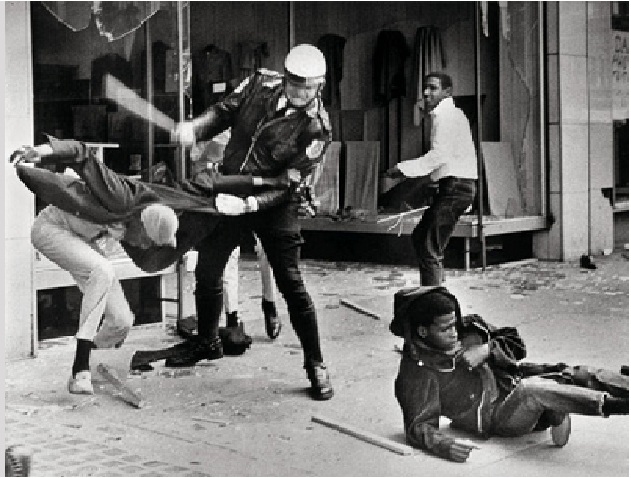

When over 1,000 sanitation workers took to the streets of downtown Memphis on 22 February in a protest action along Main Street, they were attacked by the police with clubs and mace. These repressive measures only hardened their position and served to mobilise community-wide and national support for the strike.

Interestingly enough, the national union leadership of AFSCME headed at the time by Jerry Wurf, suggested to the African American workers that they end the strike amid this escalation by the police. The workers and the community rejected this outright. The strike forged forward throughout February and into mid-March when King agreed to come to Memphis and deliver a speech to the workers and their supporters.

The Memphis sanitation workers’ strike and the citywide mobilisation were clearly in line with the aims and objectives of the PPC. Here was a signature struggle, which combined the plight of low-wage workers with the fight against institutional racism and state repression.

A victory in Memphis would provide the necessary impetus and momentum in taking the PPC to Washington DC in the following weeks. The alliance between the Civil Rights Movement and Labour would be of profound significance in exposing the duplicity of the Democratic Party threatening its electoral base in an election year when the disastrous results of the Vietnam War was plain for all to witness.

1968 was also the “Year of the Heroic Guerrilla” in honour of the martyred Che Ernesto Guevara who had been killed at the beckoning of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) the previous year in Bolivia. As the urban rebellions became more violent each summer, 1968 was anticipated to be an even more revolutionary year.

There were plans for a boycott of the Olympics by African American athletes. A nationwide campaign to free Black Panther Party leader Huey P. Newton, awaiting trial for the murder of a white police officer in Oakland, California, had galvanised youth throughout the country. People in African American communities across the US were breaking with the inferiority complexes, which were imposed by the system of national oppression and institutional racism. A strong emphasis was being placed on national pride and the study of African American and African history and culture.

In Detroit, the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM) was founded leading so-called wildcat strikes in the automobile plants, threatening the system of capitalism at the point of production. DRUM and later the League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW) saw the African American working class as the vanguard of the revolutionary movement due to their strategic position within industry.

On the evening of 28 March 1968, Memphis Mayor Loeb requested the intervention of the National Guard amid vicious attacks by local police resulting in beatings, arrests and the execution death of 16-year-old Larry Payne. Thousands of armed troops were seen on the streets of the city the following day in an effort to prevent further unrest. However, the demonstrations by the sanitation workers continued.

An entry from the King Encyclopaedia from Stanford University chronicled the situation in Memphis: “Memphis city officials estimated that 22,000 students skipped school that day (28 March 1968) to participate in the demonstration. King arrived late and found a massive crowd on the brink of chaos. Lawson and King led the march together but quickly called off the demonstration as violence began to erupt. King was whisked away to a nearby hotel, and Lawson told the mass of people to turn around and go back to the church. In the chaos that followed, downtown shops were looted, and a 16-year-old was shot and killed by a policeman” (King Encyclopaedia, no date)

The same report continues recounting that: “At a news conference, King said that he had been unaware of the divisions within the community, particularly of the presence of a black youth group committed to ‘Black Power’ called the ‘Invaders’, who were accused of starting the violence. He (King) arrived on 3 April and was persuaded to speak by a crowd of dedicated sanitation workers who had braved another storm to hear him. A weary King preached about his own mortality, telling the group, ‘Like anybody, I would like to live a long life—longevity has its place. But I am not concerned about that now… I have seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land”. (King Encyclopaedia, no date)

The following day, 4 April 1968, King was gunned down while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel near downtown Memphis at around 6:00pm. Once the news broke nationally, demonstrations and mass rebellions erupted throughout the country.

In Washington, DC where the PPC was scheduled to begin in a matter of weeks, the community erupted in rebellion. Students walked out of school while thousands of people attacked businesses and other symbols of the status quo. Federal troops were ordered into the nation’s capital to take up positions at strategic locations including the White House and the Capitol building.

Whither the Poor People’s Campaign?

Despite the assassination of King and the subsequent rebellions, the PPC organising continued. The mobilisation was delayed by several weeks however it did commence by late April and early May of 1968.

According to the PPC “The Campaign (of 1968) was organised into three phases. The first was to construct a shantytown, on the National Mall between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument. The next phase was to begin public demonstrations, mass nonviolent civil disobedience, and mass arrests to protest the plight of poverty in this country. The third and final phase of the Campaign was to launch a nationwide boycott of major industries and shopping areas to prompt business leaders to pressure Congress into meeting the demands of the Campaign” (Poor People Campaign, no date).

Significance of 1968 to 2018

Real wages went in precipitous decline beginning in the mid-to-late 1970s. Manufacturing and mining facilities in the areas of steel, auto, and energy production lost millions of jobs. Many of these jobs went into the Southern US while others were taken off shore where the potential for greater returns on investments existed.

One impact of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements of the 1950s through the 1970s was to raise expectations across a broad spectrum of society. Other oppressed nations and marginalised groups demanded their rights aimed at securing gender equity, disability rights, an end to sexual minorities bigotry and exclusion along with addressing problems of grievance redress within the workplace.

This process continued all through the 1980s as well when even white-collar employees were also subjected to downsizing and wage cuts. Classrooms were overcrowded; the environmental degradation of the central cities needed to be corrected, healthcare facilities and workers were being eroded, while the lack of healthy foods and recreation was the order of the day. Instead, the prison population increased by 500 percent between 1980 and today.

The reconstruction of the urban, suburban and rural areas has still not been carried out after repeated promises of both Republican and Democratic administrations over the previous four decades

Here in Detroit we have borne the brunt of the economic crisis. During the first decade of the 21st century, the city was the first victim nationally of predatory lending by the financial institutions. This was done in housing and municipal services. Our schools were systematically plundered by the banks with the legal backing of state governments and city administrations.

Why we need a revolutionary party

The only way in which we can reverse this situation is through organisational development, which brings together the most dedicated segments of the population under a programme of action that is aimed at targeting those responsible for the crisis. African Americans must be mobilised politically outside the stifling confines of the Democratic and Republican parties. Socialism is the only solution to the problems of institutional racism and exploitation by the billionaire ruling class.

* Abayomi Azikiwe is Editor at Pan-African News Wire

References

1. Poorpeoplescampaign.org, n.d. Poor People’s Campaign [online] Available at: https://poorpeoplescampaign.org/index.php/poor-peoples-campaign-1968/ [Accessed 14 March 2018]

2. Kingencyclopedia, n.d. Martin Luther King, JR. And The Global Freedom Struggle:Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike (1968) [online] Available at: http://kingencyclopedia.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/encyclopedia/enc_memphis_sanitation_workers_strike_1968/ [Accessed 14 March 2018]