The idea of Europeans establishing in Benin City a permanent display of looted Benin artefacts that continue to be in European ownership should be considered by every African as an insult to Nigerians and African peoples. Successors to looters become arbiters of the location and display of Benin artefacts. The wishes of the Oba of Benin are simply ignored. The Benin artefacts should be returned to the Oba of Benin and his people who may decide to organize a display showing artefacts that were looted in 1897 by a violent British army.

‘We, Europeans, who have received and transmitted and continue to transmit these objects, are on the side of the conquerors. To a certain extent, this is also a ‘heritage that weighs us down’. But there is no fatality. The good news is that in 2017 the history of Europe being what it is and has also been for centuries, a history of enmity between our nations of bloody wars and discriminations painfully overcome after the Second World War, we have within ourselves the sources and resources to understand the sadness, or the anger or hatred of those who, in other tropics, much further away, poorer, weaker, and have been subjected in the past to the intensive absorbing power of our continent. Or to put it simply: it would be sufficient today to make a very tiny effort of introspection and a slight step aside for us to enter into empathy with the dispossessed peoples’’ Bénédicte Savoy [1]

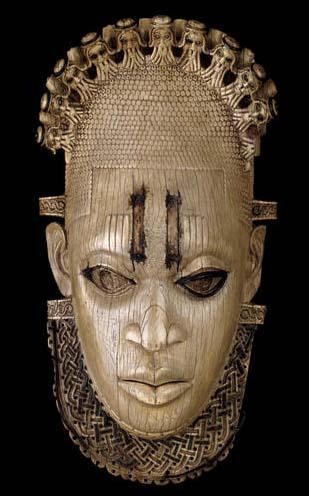

Queen-Mother Idia, Benin, Nigeria, now in British Museum, London, United Kingdom.

I read with great interest an article entitled ’University-owned Benin collections may be loaned to Nigeria’ written by Monty Fynn on 4 April 2017, in Varsity, independent student online newspaper of the University of Cambridge. [2]

The article reports that an agreement was reached at meeting of a so-called Benin Dialogue Group that met in Cambridge during the first week of April 2017 with delegations of the Benin Court, Nigerian museums, and a number of European museums with major Benin collections to establish in Benin City an exhibition of a certain number of Benin artefacts loaned by European museums. According to the article, ‘the display will consist of rotating material from a consortium of European museums.’ [3] There are no details about which artefacts will be in the projected display or about the museums that will make contributions. We do not know whether the British Museum, the museum that holds the greatest number of the looted Benin artefacts, will be participating in this project, or whether any artefacts from British museums will be loaned and when this project will start. The participation of the British Museum cannot be taken for granted. When the museums met in 2013 to draw the so-called Benin Plan of Action, the venerable museum did not participate owing to alleged logistic difficulties to travel to Benin.

The reported information seems to have come from a statement by Prince Gregory Akenzua. A spokesperson of the University of Cambridge is also reported to have stated that the agreement builds on the Benin Plan of Action of 2013. We prefer not to comment here on that miserable document. [4] It may be symptomatic of the nature of the discussions said to be going on that the public receives very little information. We are to be surprised by a scheme that may raise many controversies.

In the absence of more details about the proposed display in Benin City, we reserve our right to make detailed comments later. Meanwhile, we offer a few preliminary comments on the available information. We believe that ideas should be discussed vigorously before they are concretized and before it is to late to change or challenge them. The long 500-year period of relations between Africa and Europe has taught us several lessons which should not be ignored even by museum officials.

We should pay careful attention to the idea of successors to the looters of the Benin artefacts making a loan to the rightful and legitimate owners of the artefacts looted in 1897 by the members of the nefarious British Punitive Expedition. Since when do looters or their successors loan the very stolen objects to the owners instead of simply and correctly returning them? What will be the status of the Benin artefacts that were wrenched from their locations with great violence and mayhem? Would this mean that, for instance, Nigerians cannot send any of the artefacts to Ghanaians for a Pan African festival in Accra without the consent of Europeans? Are we moving forwards or backwards? We should be aware that by accepting a loan of looted Benin artefacts, one could be considered to have recognized thereby the ownership or ownership rights of the museums in the artefacts. One will be estopped, in English law, from asserting a contrary position later. So far, no such recognition of ownership has been formally accepted. Once we reach such a situation, we can forget all our claims for restitution of looted African artefacts. A dangerous precedent would have been set for other African States.

It would be interesting to know what price Nigerians would pay for this revolving display of Benin artefacts. Would they have to pay money for the loan? Would they be paying for the loan of their own artefacts to the successors of the notorious looters? Or would there be some other consideration such as renouncing forever any claim to the looted artefacts? There is in the museum world, as elsewhere, no such thing as free lunch. The danger here is that much of the arrangements between African museums and their European counterparts are usually shrouded in mystery and the public never gets to know the details. The need for transparency is not felt by many African and European museum officials. Many museums appear to be run almost as secret societies. No one knows about their expenditures and they react badly to questions about details of their finances. They do not see it as a duty to inform the public about arrangements with other institutions.

They invite the public to see and admire the objects in exhibition but do not want an inquisitive public that seeks information about the administration of the museum. For example, nobody knows what the Russians paid for having a Parthenon marble flown to St. Petersburg for exhibition. We also do not know how much Nigeria received for Benin: Kings and Rituals-Court Arts from Nigeria in Vienna, Paris, Berlin and Chicago. Nor is one informed about the expenses of Kingdom of Ife: Sculptures from West Africa.

Members of the nefarious Punitive Expedition of 1897 posing proudly with looted Benin artefacts

It is true though that many African governments have not provided sufficient funds for their museums which must often rely on external funds from the very states that are holding our looted artefacts. That clearly weakens the bargaining position of African museum officials in their dealings with European museums. Think of the deleterious effect of such situations on the production of knowledge in museum studies. The often-stated commitment of African governments to African culture is not generally followed by any concrete acts. Hardly any politician follows the example of Léopold Sédar Senghor who made sure that the budget of Senegal made sufficient provisions for arts and culture.

The idea of Europeans establishing in Benin City a permanent display of looted Benin artefacts that continue to be in European ownership should be considered by every African as an insult to Nigerians and African peoples. Successors to looters become arbiters of the location and display of Benin artefacts. The wishes of the Oba of Benin are simply ignored. The Benin artefacts should be returned to the Oba of Benin and his people who may decide to organize a display showing artefacts that were looted in 1897 by a violent British army. This would be the true history of the Benin Bronzes, however painful and shameful this may be for some persons and institutions. For the sake of all those who lost their lives and properties in the notorious invasion, the true story of Benin should be preserved. Falsification and distortion of history will not do.

Nigerian officials should finally pay some attention to the so-called manifest destiny of Nigeria on the African continent and bear in mind that any arrangement they reach with European museums and governments will be cited as precedent for similar agreements regarding restitution of looted artefacts from other African States.

Head of an Oba, Benin, Nigeria, now in Bristol Museum, Bristol, United Kingdom of Great Britain.

The report on the proposed display of Benin artefacts on loan from European museums demonstrates once more, if another proof were necessary, European contempt for Africans and our intelligence. How could anyone, conversant with the history of the violent detachment of the artefacts from the palace of Oba Ovonramwen in 1897 make such a proposal? Would Europeans accept such a proposal if their looted treasures were in Nigeria and were shown from time to time in London and then returned to Benin where they would be kept for good? Do Benin artefacts belong to Nigerian history or European history? And how can any respectable African agree to such a proposal? Where is the self-respect of African representatives?

Queen-Mother Idia, Benin, Nigeria, now in the Ethnological Museum, Berlin, Germany.

We expect nothing short of the full restitution of the famous Benin bronzes such as the hip-mask of Queen Mother Idia, now in the British Museum, the bust of Queen-Mother Idia, now in the Ethnological Museum, Berlin, the plaque of Oba Ozolua and his retainers, now in World Museum, formerly Ethnological Museum, Vienna, the altar with Oba Ewuakpe, in the Ethnological Museum, Berlin, Germany, as well as the altar with Oba Akenzua I. in the same museum. These Benin nobles must return home to occupy their rightful place in the history and culture of the Benin and Nigerian peoples.

Altar group with Oba Ewuakpe, Benin, Nigeria, now in Ethnological Museum, Berlin, Germany.

The famous and well-known bronzes, relating to Benin history and culture, should be returned to Benin unless the Oba of Benin agrees that some of them may stay abroad. It would not be acceptable that European museums select for their own use the better-known objects and return to Nigeria lesser known artefacts.

What the people of Benin need is not a museum of rotating artefacts, here today in Benin City and back tomorrow in Berlin or London. We do not know whether other countries have such a system, apart from special exhibitions. In most countries, historical figures, such as Queen-Mother Idia, would have their statues standing at a definite place in a definite museum for decades. Students and pupils would visit such figures at places known by all. But how do you teach the public about such personalities when they are constantly changing and returning to the countries that have been keeping them since the invasion of 1897? How do you create and build knowledge on such a basis? No one could prepare a history of Benin for schools on such basis.

Regarding the number of artefacts to be returned, one would hope that the Nigerians may agree to leave a few in European museums but the majority should be returned. For example, the Ethnological, Berlin, holds some 508 Benin artefacts. There is no reason why at least 300 should not be returned to their original abode in the palace of the Oba of Benin from where they were looted. [5] We believe Benin should have most of Benin artefacts just as the Europeans have most European artefacts. Alas, Westerners have banned justice and morality from issues of restitution. For example, instead of seriously considering returning many Benin artefacts to Benin City, German museum officials are busy working on how they can display the artefacts in the new Humboldt Forum now under construction in Berlin. [6] Those holding looted items do not seem to have any urge to return them.

Western museums holding looted Benin artefacts are not likely to change their attitudes so long as countries like Nigeria do not increase the pressure on them to release stolen objects. Since independence in 1960, Nigerian parliaments and governments have frequently requested the restitution of the looted artefacts and have mandated officials to contact the holders but so far not even one of the looted artefacts in the museums has been returned. In a speech delivered in Vienna, at a conference on New Cultures of Collaboration, Sharing of Collections and Quest for Restitution: The Beni Case, Vienna, December 2-3, 2010, the Director-General of the National Commission on Museums and Monuments (NCMM), Nigeria, invited what he called ‘international museums’ to establish museums with branches in source countries. [7]

The idea is not new and has been mentioned by a Nigerian scholar some decades ago. We consider this idea very dangerous. When we have Western museums known for holding looted Nigerian artefacts, refusing to return any, it does not seem right to invite them to open branches in Nigeria. In effect, one is inviting them to open a depot at the source for the looted/stolen artefacts in their museums. As the Director-General would know from the examples of British lootings he mentioned, the universal museums, (which he prefers to call international museums) have always played a major role in such lootings. For example, Richard Rivington Holmes, an assistant in the manuscripts department of the British Museum, had accompanied the expedition against Magdala, Ethiopia, as an archaeologist. He acquired a number of objects for the British Museum, including around 300 manuscripts which are now housed in the British Library. http://www.britishmuseum.org [8]

Whether in Beijing, (China,1860), Magdala, (Ethiopia, 1868), Kumasi, (Gold Coast, Ghana, 1874) or Benin City, (Nigeria, 1897), it is obvious that the looted articles were not taken at random by wild soldiers hungry for loot; the objects were taken with advice from experts from museums or auction houses. Even in our days when meetings are held on ‘what objects we should save in case of war’, this is usually a training seminar by experts to instruct on what is valuable in a museum or palace which one should take out. Looters in time of invasions do not simply loot on instinct but with knowledge, training and skill.

We can imagine the consequences of inviting universal museums to open branches in Nigeria, as regards corruption and looting of artefacts. One facilitates the transfer of looted artefacts from Nigeria. We used to think that one of the major mandates of the NCMM was to secure the return of the thousands of Nigerian artefacts abroad but instead it now seems to be inviting the illegal holders of the artefacts to open branches in Nigeria. Something is not right here.

Readers may have noticed that it is only when an international meeting is on the question of restitution of looted African artefacts that the word ‘sharing’ features prominently. There has never been a meeting between Africans and Westerners on artefacts where sharing is mentioned in connection with European artefacts. We have mentioned often that we could also share with Europeans their cultural artefacts but nobody has taken up the suggestion or criticised it. It appears the Europeans are so shocked by the idea that a European painting, for example, a Turner or Picasso could be sent to an African museum. The European attitude is: mine is mine, yours is ours. It appears that those who talk about sharing are not really interested at all in sharing the looted artefacts they hold. What they mean by ‘sharing’ is that Africans agree to their keeping the objects and from time to time they may display one or two objects to Africans. Otherwise where is the difficulty for the Ethnological Museum of Berlin sharing the 508 objects it has with Benin? Has the museum shown its goodwill by, for example, sending a few of the artefacts to Benin until there is agreement on the eventual number of artefacts to be returned? Numbers are not even being discussed.

African delegates are sent to argue for the restitution of our looted artefacts and they end with discussions on sharing the looted African artefacts with Europeans. It seems in the opinion of many Europeans, Africans do not even deserve to have African artefacts. If Nigerian representatives feel they cannot, after all these years, make any progress towards the recovery of Nigerian artefacts, they should inform their people and government so that they may take other measures and relieve them of their impossible mandate. Above all, there should be no attempt to create any illusions that Nigeria has been successful in the recovery of looted artefacts. When Nigerian peoples, parliaments and governments request the return of Nigerian treasures abroad, they are surely not thinking of customs and police seizures of criminal attempts to transfer artefacts abroad: they think of the thousands of Nigerian artefacts in museums and other institutions in the West - they think of the Benin bronzes in the British Museum, London, Ethnological Museum, Berlin, World Museum, Vienna and Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York and Museé du quai Branly, Paris.

Routine police and customs seizures of unlawful attempts to smuggle Nigerian artefacts should not be confused with efforts at restitution that have so far failed. The return of some of the artefacts looted in 1897 was not a result of Nigerian efforts but a decision by an individual British subject, Dr. Mark Walker, who, disturbed by his conscience that the artefacts inherited from his great-grand father were secured through violence against the Benin people, returned them to Benin. [9] The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, voluntarily returned 8 pieces of looted art to Nigeria. Again, this was not due to any Nigerian demand or pressure. Moreover, the museum’s action was related only to artefacts stolen after 1970 thus excluded artefacts looted in 1897. The museum is still holding artefacts stolen in 1897.

Two artefacts returned by Dr. Mark Walker. rbp.blogspot.com

The lack of enthusiasm in pursuing the recovery of looted Nigerian treasures has been noted by many. Plankensteiner, a curator of the exhibition, Benin Kings and Rituals-Court Arts from Nigeria, has written:

‘Sotheby’s had informed the Nigerian authorities in advance about the upcoming sale with an official letter to the Nigerian National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM). The Art Newspaper reported that Nigerian official bodies made no formal claims in the end; also, an approach to the family seemingly never happened, although it had been planned by officials of the NCMM’.

‘Willett also deplored the slow reaction of the NCMM in replying to reports they received from customs or international colleagues who informed them about detected stolen objects and in officially claiming them back.’ [10]

It is interesting to note that the auction sale of a Benin bronze, Queen-Mother Idia mask, mentioned above was finally aborted because of agitation by Nigerian students abroad. There was no input from Nigerian authorities nor was there any follow-up on the issue by Nigeria. The Galway family may have sold the mask privately without too much publicity. Again, Cambridge students succeeded in making the university authorities consider the return of the Benin Cockerel without any real input from Nigerian authorities and yet we are given the impression that the student agitation was somehow the result of the so-called quiet diplomacy.

Prof. Wilhelm Östberg, has also stated that Nigerian officials may have other interests in lending national treasures without seeking reciprocity and that may also explain why the same officials are not keen to submit formal requests for restitution:

‘There are many ways to develop relationships besides returning museum objects. Informally, it also appears that different kinds of collaboration that are currently in progress are more important to Nigerian museums. That might explain why Nigeria has not registered any formal demand for the return of the Benin collections, but has preferred to engage in dialogue and cooperation with museums that have Benin collections. It seems Nigeria is chary of bringing the matter to a head. How does one otherwise explain that the National Museum of Nigeria was willing to lend its extensive and unique collection of Ife art to the British Museum for a special exhibition 2010, without demanding reciprocity?’

[11] No one has challenged this assertion by the former Director of the Ethnological Museum, Stockholm, a museum that organized with Nigeria an exhibition on Benin artefacts in Stockholm.

We do not know exactly how many artefacts were stolen in 1897 but we accept that more than 3,000 artefacts were looted as stated in a plea before the British House of Commons by Prince Edun Akenzua, great-grandson of Oba Ovonramwen in whose reign the artefacts were removed from the Oba’s palace. [12] What is more important for the issue at hand is the number of Benin artefacts that the various Western museums hold. This number could be easily established if the museums were interested in helping. As stated in the annex below, most museums refuse to divulge the number of Benin artefacts they hold. And yet they are public institutions or claim to serve the public.

It would be interesting to know how the displayed Benin objects would be insured. Who will pay for the insurance? Would it be the European museums who would be acting as ‘owner’ or Nigeria as a ‘user’? Would the objects be insured with a European insurance company or a Nigeria company? Would the details be made known to taxpayers? We recall that during FESTAC the proposal to bring home the hip-mask of Queen-Mother Idia was accompanied by exorbitant claims for insurance that Nigeria was finally unable or unwilling to accept.

We note that the discussions on the return of Benin bronzes have so far involved only European museums. What about American museums? Is the British government, that is ultimately responsible for the looting and dispersal of the Benin artefacts, going to assume its responsibility, and ensure that the looted artefacts are returned or will the Nigerians have to negotiate separately with Americans and thus free the British Government from its responsibility of having sent its troops to Benin who looted the artefacts?

We would expect Nigerian officials and their European counterparts to elaborate a set of principles that would make the choice of artefacts to be returned apparent and recognizable. The whole process should be transparent and not be shrouded in a cloak and dagger operation as some are wont to do. The Nigerian public, the European public and students of Benin culture should be enabled to follow discussions and measures on a matter of a wider public concern. Nor should Nigerians accept a procedure that would keep the people of Benin waiting for another hundred years before they finally see the return of their valuable treasures. The proposed arrangement would turn looters and their successors into owners and make owners and their successors miserable beggars. The arrangement would clearly reduce the pressure on the holders of looted artefacts to return them.

It seems that international cooperation and solidarity cease for many Westerners when it comes to restitution of looted African artefacts. They will do everything except return them to the legitimate owners. Westerners, even today, seem to have a deep-seated reluctance to admit that slavery, colonialism and imperialism and indiscriminate use of violence against Africans are all wrong, and hence their unwillingness to restore looted African artefacts as they have done for other peoples. Compensation for loss of life and destruction of property are clearly not on their agenda. And they find Africans to accept this situation.

The latest proposal to establish a rotating display of Benin artefacts in Benin City shows clearly that Western museums have not yet abandoned their pretentious claim to universalism which was used to justify their retention of looted artefacts from around the world. That unfounded and arrogant racist claim based on imperialist and colonialist assumptions about Caucasian superiority, supported by some Enlightenment philosophers, has been demolished in the last decades and is no longer directly presented but still appears to be the basis of many Western thoughts and actions. [13] The notion still seems to reign in museum circles but must African officials and intellectuals accept such racists beliefs, even if they have done their apprenticeship and studies in Western universities and museums?

Contemporary Westerners purport to condemn the imperialism and colonialism of their forebears but are unwilling to give up any of the artefacts looted during previous eras. They appear in this light to be worse than their predecessors. Could Western museums be the last bastions of colonialism and imperialism by holding on to looted artefacts which should have been returned at the time of independence?

Does anybody find it proper to propose to the Oba of Benin, owner of the Benin bronzes, the sharing of the looted Benin artefacts in the western world? Do our senses of legality and morality permit such a proposal? In effect, successors to the looters are saying to the successors of the Benin owners, let us share what our predecessors stole from your ancestors. Can self-respecting Nigerians accept such a proposal and become accomplices after the fact of the looting of 1897?

Arrogance, denigration, humiliation, racism and lack of respect have been the hallmarks of Western discourse on restitution of looted African artefacts and the recent proposal of displaying Benin artefacts in Benin City is no exception. Nothing demonstrates more clearly the powerlessness of the African continent than the issue of restitution of looted African artefacts.

Future generations will marvel at those who proclaim the freedom of art and artistic creativity at every occasion but stubbornly refuse to return looted African artefacts they have been holding illegally for decades. They have hijacked the most important African contribution to the civilisation of the universal advocated by Léopold Sédar Senghor. [14]

‘But should the recipient countries continue to be so completely oblivious to the feeling of deprivation which is suffered by the loser countries? What is more, in many cases, objects which now adorn museums and private homes in the recipient countries and which are merely regarded as curios or objets d’art have overriding cultural and historical importance for the countries of origin. That is why the discussion on the restitution or return of cultural property is often accompanied by impassioned outbursts’. -Ekpo Eyo. [15]

Oba Ozolua and his retainers, Benin, Nigeria, now in World Museum, formerly Ethnological Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Notes

[1] ‘Nous, les Européens, qui avons reçu et transmis et continuons de transmettre ces objets, nous sommes du côté des vainqueurs. D’une certaine manière, cela aussi, c’est un « héritage qui nous écrase ». Mais il n’y a pas de fatalité. La bonne nouvelle, c’est qu’en 2017 l’histoire de l’Europe ayant été ce qu’elle a été aussi pendant des siècles, une histoire d’inimitiés entre nos nations, de guerres sanglantes et de discriminations péniblement surmontées après la Seconde Guerre Mondiale, nous avons à l’intérieur de nous-mêmes les sources et les ressources pour comprendre la tristesse, ou la colère, ou la haine de ceux qui, sous d’autres tropiques, plus loin, plus pauvres, plus faibles, ont été soumis par le passé à « l’intense pouvoir absorbant » de notre continent. Ou pour dire les choses simplement : il nous suffit aujourd’hui d’un minuscule effort d’introspection et d’un léger pas de côté pour entrer en empathie avec les dépossédés.’

Bénédicte Savoy, Objets du désir. Désir d’objets Histoire culturelle du patrimoine artistique en Europe. XVIIIe–XXe siècles Leçon inaugurale prononcée au Collège de France le 30 mars 2017

https://www.college-de-france.fr/site/en-benedicte-savoy/inaugural-lecture-2017-03-30-18h00.htm

The official English text of the brilliant lecture in French by Professor Savoy at the Collège de France is not yet available but I found her ideas so encouraging that I decided to provide an English translation based on the French text and the simultaneous English interpretation for my readers. We will bring the English text to the attention of readers when available.

[2] Exclusive: University-owned Benin collections may be loaned ... - Varsity

Exclusive: University-owned Benin collections may be loaned to ...

www.nigeria70.com/nigerian...university_owned_benin_collecti

Exclusive: University-owned Benin collections may be loaned to ...

www.dubnews.com/more.php?...University-owned+Benin+collec..

[3] See Annex below.

[4] K. Opoku, ‘Benin Plan of Action for Restitution: Will this ensure the return of the looted Benin artefacts,’ https://www.modernghana.com/news/449521/benin-plan-of-action-for-restitution-will-this-ensure-the.html

‘Benin Plan of Action (2) Will this miserable Project be the last word on the Looted Benin Artefacts?’ www.modernghana.com/.../benin-plan-of-action-2-will-this-mise...

K. Opoku, http://www.museum-security.org/2013/02/kwame-opoku-benin-plan-of-action-for-restitution/

[5] K. Opoku, ‘Did Germans never hear directly or indirectly Nigeria’s demand for the return of looted artefacts?’ www.africavenir.org/.../kwame-opoku-did-germans-never-hear-did germans never hear directly or indirectly nigeria's demand for ...www.museum-security.org/Kwame_Opoku_Germany_Nigeria_Benin.htm

K .Opoku, ‘Queen-Mother Idia and Others Must Return Home: Training Courses...https://www.modernghana.com/.../queen-mother-idia-and-others-.

[6] K. Opoku, ‘Germans Debate Legitimacy and Legality of Looted Artefacts in Ethnology Museum, Berlin’ www.museum-security.org

[7] Yusuf Abdallah Usman Who owns Benin artefacts? - Daily Trust https://www.dailytrust.com.ng/...owns-benin-artefacts/6103.html

I noticed that a text I translated from German has been used in this speech without any acknowledgement or mention of the source of information.

‘Dr. Andreas Lüderwaldt of the Übersee-Museum Bremen had this to say:

‘When I now look at the source and history of individual collections and objects in the Übersee-Museum Bremen which I represent here and try to trace back, then I must say that abysses will be opened up; not that the objects were appropriated with violence as in Benin. There are other possibilities of illegal acquisition; there is gentle “force”. I therefore appeal to all museum officials to research the history of their collections; we would then show more understanding for the demands for restitution.’

Both the German original and my English translation can be found in my article, ‘Benin to Berlin Ethnologisches Museum: Are Benin Bronzes made in Berlin?’ www.africavenir.org/.../content_uploads/Opoku_BeninBerlin_06.pdf

Benin to Ethologisches Museum: Are Benin Bronzes made in Berlin? ...

https://www.modernghana.com/.../benin-to-berlin-ethnologisches..

‘Wenn ich mir jetzt die Herkunft und Geschichte einzelner Sammlungen und Objekte im Übersee-Museum Bremen, für das ich hier spreche, ansehe und versuche zurückzuverfolgen, so muß ich sagen, daß sich dabei Abgründe auftun; nicht daß die Dinge mit Gewalt wie im Falle Benin angeeignet wurden. Es gibt auch andere Möglichkeiten der illegalen Beschaffung, es gibt die „sanfte“ Gewalt. Ich möchte daher an alle Museumsmitarbeiter appellieren, der Geschichte ihrer Sammlungen nachzugehen; dann dürfte auch von unserer Seite mehr Verständnis für Rückgabe-Forderungen aufgebracht werden.‘

Das Museum und die Dritte Welt, Ed. Hermann Auer, K.G.Sauer, München, New York London, Paris 1981, p.155.

The astonishing view expressed by Peter-Klaus Schuster that all objects in his museums were legally acquired is, fortunately, not shared by many of his colleagues. Lüderwaltd from the Übersee-Museum Bremen stated in an International Symposium in 1979 that: ‘When I now look at the source and history of individual collections and objects in the Übersee-Museum Bremen which I represent here and try to trace back, then I must say that abysses will be opened up; not that the objects were appropriated with violence as in Benin. There are other possibilities of illegal acquisition; there is gentle “force”. I therefore appeal to all museum officials to research the history of their collections; we would then show more understanding for the demands for restitution.’

[8] On the role of the British Museum in the Magdala looting we refer to our article, ‘A History of the World with 100 Looted Objects of Others: Global Intoxication?’ We wrote in footnote 14 as follows:

‘Richard Rivington Holmes, an assistant in the manuscripts department of The British Museum, had accompanied the expedition against Magdala, Ethiopia, as an archaeologist. He acquired a number of objects for the British Museum, including around 300 manuscripts which are now housed in the British Library.’ http://www.britishmuseum.org. Professor Richard Pankhurst has written about Richard Holmes as follows: ‘One of those present at this large-scale looting was Richard (later Sir Richard) Holmes, an Assistant Curator in the British Museum’s Department of Manuscripts, who had been appointed ‘Archaeologist’ to the expedition. He later noted in an official report that the British flag had “not been waved… much more than ten minutes” over the fort of Maqdala before he had himself entered it. Shortly afterwards, while night was falling, he met a British soldier who was carrying the golden crown of the Abun, or head of the Ethiopian church, and a “solid gold chalice” weighing “at least 6 lb”, i.e. pounds. Holmes purchased them both for four pounds Sterling. He was also offered several large manuscripts, but declined to buy them as they were too heavy for him to carry” “The Ethiopian Millennium – and the Question of Ethiopia’s Cultural Restitution” nazret.com http://www.elginism.com. An internet site provides the following: The invading British force included a number of mysterious civilians and an "official archaeologist", a Mr Richard Holmes, said to have secured "many interesting items" from Magdala. Holmes was an assistant in the British Museum's Department of Manuscripts, but soon after the successful war became Sir Richard Rivington Holmes KCVO, Keeper of the Queen's Pictures and Librarian to Queen Victoria and her son Edward VII at Windsor Castle (from 1870 until 1906). http://www.elecbk.com/facts.htm

[9] Kwame Opoku – A Briton Returns Two Looted Benin Artefacts ...

www.museum-security.org/.../kwame-opoku-a-briton-returns-tw..

[10] Barbara Plankensteiner, ‘The Benin treasures: difficult legacy and contested heritage’, pp.139-143, in Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin and Lyndel V. Prott (eds), Cultural Property and Contested Ownership, 2016, Routledge, New York.

See also, K. Opoku, Recovering Nigeria’s terracotta - Afrikanet.info

www.afrikanet.info/.../RECOVERING_NIGERIA__S_TERR

LET OTHERS LOOT FOR YOU: LOOTING OF AFRICAN ARTEFACTS ...

https://www.modernghana.com/.../let-others-loot-for-you-looting..

[11] Wilhelm Östberg, ‘ The Coveted Treasures of the Kingdom of Benin’, p.68, Whose Objects, catalogue of exhibition at the Museum of Ethnography, Stockholm, 2010, Etnografiska museet (Museum of Ethnography.

[12] Appendix 21-The Case of Benin Memorandum submitted by Prince Edun Akenzua www.publications.parliament.uk › ... › Culture, Media and Spor

[13] The major Western museums that have hitherto pretended to be ‘universal museums’ are described by the Director -General of NCMM as ‘international museums. Museums such as British Museum, London, Louvre, Paris Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York, Ethnological Museum, Berlin, and Ethnological Museum, Vienna are neither universal nor international no matter how much they pretend. A universal museum would be a museum set up by representatives of the peoples or states of the universe. So far, no such museum exists. These major museums have undoubtedly looted materials from almost the entire universe. Is that what makes them universal? Are they to be designated by the looted objects they are illegally holding? These museums are also not international but national. The British Museum, for example, is a British museum established, financed and administered by Britain. Its name indicates its status. An international museum properly speaking would be a museum set by at least two nations, financed and administered by them. The Trustees of British Museum are appointed by the British Queen and the Prime Minister of the UK.

Because of maximum criticism, the major museums dropped gradually the designation ‘universal museums’ and took the designation ‘encyclopaedic museum’ but this did not seem to protect them from continued criticism. They are now trying ‘international museum’ but this will also not prevent their being criticised so long as these changes of names are mainly intended to justify their illegal holding of the artefacts of other countries and cultures.

K. Opoku, ‘Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums: Singular Failure of an Arrogant Imperialist Project’,

declaration on the importance and value of universal museums https://www.modernghana.com/.../declaration-on-the-importance...

K. Opoku, ‘When will Everybody Finally Accept that the British Museum is a British Institution? Comments on a Lecture by Neil Macgregor.’ www.elginism.com

when will everybody finally accept that the british museum is a british ...

https://www.modernghana.com/.../when-will-everybody-finally-a..

K. Opoku, ‘Is Nationalism as such a dangerous Phenomenon for Culture and Stolen/Looted Cultural

is nationalism as such a dangerous phenomenon for culture and ...

https://www.modernghana.com/.../is-nationalism-as-such-a-dange

‘Is the Declaration on the Value and Importance of Universal Museums Now Worthless? Comments on Imperialist Museology’, Is the Declaration of the Value and Importance of the Universal Museums

www.museum-security.org/opoku_universal_museums.htm The Cultural Nationalists are all on the other side

https://www.modernghana.com/.../the-cultural-nationalists-are-all...

Immanuel Wallerstein, European Universalism-The Rhetoric of Power,2006, The New Press,New York.

[14] Although we disagree with most of the theories of Senghor, especially his characterization of differences between African and European mentalities, as well as his ideas regarding the civilisation of the universal, this theory has the advantage that it allows for the existence of diverse cultures without any one culture claiming inherent supremacy. Senghor’s universalism is preferable to the universalism of the Europeans which is often no more than a barefaced attempt to justify the conquest and destruction of non-European peoples and the looting of their national treasures and resources. This is clearly demonstrated by the writings of the supporters of the so-called universal museums and their practice. It is very difficult to understand the support or sympathy exhibited by some Africans towards a theory supporting European conquests and destruction in Africa, Asia and in the Americas.

[15] Ekpo Eyo, ‘Return and restitution of cultural property -Nigeria’ Return and restitution of cultural property; Museum; Vol.:XXXI, 1; 1979 unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001273/127315eo.pdf Archaeologist, Professor and Museologist Ekpo Eyo Dies

Pair of leopard figures, now in the Royal Collection Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, London, UK. The commanders of the British Punitive Expedition force to Benin in 1897 sent a pair of leopards to the British Queen soon after the looting and burning of Benin City.

ANNEX

SHORT LIST OF HOLDERS OF BENIN BRONZES

Almost every Western museum has some Benin objects. Here is a short list of some of the places where the Benin Bronzes are to be found and their numbers. Various catalogues of exhibitions on Benin art or African art also list the private collections of the Benin Bronzes. Many museums refuse to inform the public about the number of Benin artefacts they have and do not display permanently artefacts in their possession since they do not have enough space. See Dohlvik, Charlotta (May 2006). Museums and Their Voices: A Contemporary Study of the Benin Bronzes (PDF). International Museum Studies, p.26.

A museum such as World Museum, Vienna, formerly Ethnological Museum, Vienna, has closed for 17 years (2000-2017) the African section where the Benin artefacts are, apparently due to repair works which are not likely to be finished before 2017.

Berlin – Ethnological Museum 508-580.

Boston, - Museum of Fine Arts 28.

Chicago – Art Institute of Chicago 20, Field Museum 400

Cologne – Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum 73.

Glasgow _ Kelvingrove and St, Mungo's Museum of Religious Life 22

Hamburg – Ethnological Museum, Museum of Arts and Crafts 196.

Dresden – State Museum of Ethnology 182.

Leipzig – Ethnological Museum 87.

Leiden – National Museum of Ethnology 98.

London – British Museum 700.

New York – Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art 163.

Oxford – Pitt-Rivers Museum/ Pitt-Rivers country residence, Rushmore in Farnham/Dorset 327.

Philadelphia -. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology 100.

Stockholm – Museum of Ethnography 43

Stuttgart – Linden Museum-State Museum of Ethnology 80.

Vienna – World Museum, formerly Ethnological Museum 167.

Altar Group with Oba Akenzua I, Benin, Nigeria, now in Ethnological Museum, Berlin,

- Log in to post comments

- 14657 reads