Anti-slavery campaigns in Britain and their impact on the formation of the United States

The leaders of the 18th century separatist movement from England were not motivated by a genuine desire for freedom and equality.

If the so-called American Revolution of 1776 was truly committed to breaking with monarchical and autocratic rule from the United Kingdom then why did slavery grow at a rapid rate after the achievement of independence of the former 13 colonies in North America?

This is an important political question since even in the 21st century there are repeated references by elected officials in both houses of Congress, the White House and the Supreme Court to the “Founding Fathers” and “Framers of the Constitution.” What is not mentioned by these career politicians and lifetime jurists is that many of the authors of the United States Constitution were large-scale slave owners themselves.

These wealthy landowners and slave masters did not see any reason to liberate the more than 700,000 Africans living in the former colonies by the conclusion of the 1780s. The existence of slavery was quite profitable and with the discovery of the cotton gin in 1793, the expansion of involuntary servitude across the South and extending further west empowered the planters to the point where as a result of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 they were able to dominate the House of Representatives through a provision declaring that enslaved Africans could be counted as three-fifths of a person.

In an article published by Paul Finkelman of the Albany Law School in New York: “The three-fifths clause provided the extra proslavery representatives in the House to secure the passage of the Missouri Compromise of 1820 (bringing Missouri in as a slave state); the annexation in 1845 of Texas, which was described at the time as an ‘empire for slavery’; the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850; the law allowing slavery in Utah and New Mexico; and the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 (which opened the Great Plains and Rocky Mountain territories to slavery). None of these laws could have been passed without the representatives created by counting slaves under the three-fifths clause.”[[i]]

Some aspects of the anti-slavery movement in Britain in the late 18th century

While the descendants of the British colonialists were divorcing themselves from the Crown, a burgeoning anti-slavery movement was taking hold in England. London was the largest centre of the Atlantic Slave Trade where enormous profits earned from the exploitation of African labour was set to spawn the rise of industrial capitalism in the 19th century.

An important episode in the history of jurisprudence related to the legal basis for African enslavement was the case of Somerset v. Stewart, which was heard and decided in London during 1772. James Somerset was an African purchased in Virginia and held by a Scottish merchant and customs officer. [[ii]]

Somerset was brought from Virginia to England by Charles Stewart with the intent to continue his enslavement. Somerset fled from captivity and was later imprisoned. He filed suit in the British courts demanding his freedom based upon the lack of sufficient English law recognising slavery within the unwritten constitution.

Although there were codes under British customary law, which reinforced slavery, the courts found that there was no legal basis for the ownership of Somerset by Stewart. The although narrow ruling was not intended to free enslaved Africans from bondage, it provided the impetus for the abolitionist movement in both Britain and what later became known as the United States.

A summary of the ruling states that: “In a decision handed down by William Murray, Baron (later Earl) of Mansfield and Chief Justice of the Court of King’s Bench, the court narrowly held that ‘a master could not seize a slave in England and detain him preparatory to sending him out of the realm to be sold’ and that habeas corpus was a constitutional right available to slaves to forestall such seizure, deportation and sale because they were not chattel, or mere property, they were servants and thus persons invested with certain (but certainly limited) constitutional protections.”[[iii]]

The decision was hailed by the African population and anti-slavery proponents in Britain. Granville Sharp, a staunch advocate for the elimination of slavery had taken up the case on behalf of Somerset advising his lawyers on the arguments put forward in the case.

Sharp had written a tract in 1769 entitled “A Representation of the Injustice and Dangerous Tendency of Tolerating Slavery”, considered a foundational publication of the abolitionist movement of the 18th century. Gaining a reputation through the Somerset Case and previous attempts at freeing enslaved Africans, Sharp was approached by Olaudah Equiano in 1781 to seek his support in exposing the Zong massacre. [[iv]]

Equiano, also known as Gustavus Vassa, wrote in his autobiography that he was captured in West Africa in the region now known as southeast Nigeria. He would be taken to Virginia where he worked to purchase his own freedom. Later he would be a co-founder of the Sons of Africa, an organisation of emancipated people in Britain committed to the elimination of slavery. [[v]]

The Zong was a British slave ship from Liverpool, which captured 400 Africans setting sail later from Accra in West Africa. While traveling to the Caribbean island of Jamaica, many of the people on board were sickened including both European sailors and enslaved Africans.

After the deaths of 70 slaves and sailors on board, the captain Luke Collingwood authorised the throwing of Africans overboard resulting in the brutal deaths of another 133 people. This was done for the purpose of collecting insurance on the enslaved. The incident was widely publicised and consequently mobilised the Free African community and abolitionist movement in Britain.

Claims for the payment of the insurance were denied by the Baron of Mansfield who had ruled in the Somerset decision. Nonetheless, despite gallant attempts by abolitionists, the European crew was never convicted of murder. The ruling in the case said the killing of Africans was warranted under such circumstances as the purported lack of water, food and the prevalence of disease.

An historical website, blackpast.org, said of those in authority related to the attempt to prosecute the responsible individuals: “Great Britain’s The Solicitor General, Justice John Lee, however, refused to take up the criminal charges claiming ‘What is this claim that human people have been thrown overboard? This is a case of chattels or goods. Blacks are goods and property; it is madness to accuse these well-serving honourable men of murder… The case is the same as if wood had been thrown overboard.’”[[vi]]

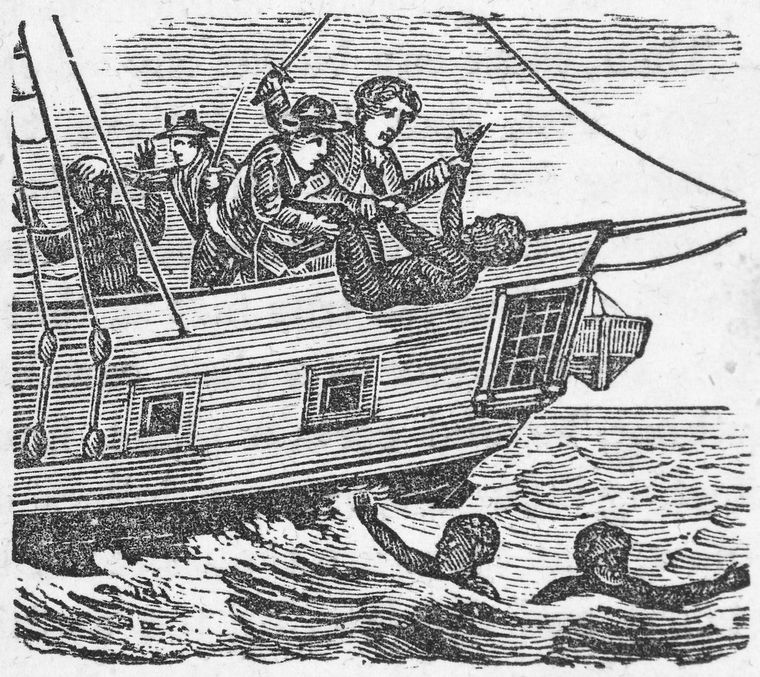

An African woman tortured by John Kimber who was acquitted of murder by British courts in 1792

Just a decade later after the acquittal of the perpetrators of the Zong massacre, Captain John Kimber was placed on trial for the torture and murder of an African woman aboard the slave ship Recovery. Through the efforts of the abolitionists in Britain, Kimber was brought before the court, even though he was not convicted.

These developments illustrated the inherent racism within the British legal system. Such occurrences prompted the persistence of the anti-slavery campaigns. Africans such as Equiano and Ottobah Cugoano through the Sons of Africa grouping spread the consciousness related to the humanity of Black people. [[vii]]

The Sons of Africa worked closely with the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Thomas Clarkson, a co-founder of the Society, along with ten other anti-slavery advocates, persuaded parliamentarian William Wilberforce to introduce legislation demanding the end to human bondage. However, it would take decades of work to bring about the abolition of slavery in the British Empire.

Cugoano was kidnapped by the British in the West Africa region of today’s Ghana in 1770 being taken to England. He would win his emancipation and publish a book in 1787 entitled: “Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species.”[[viii]]

As opposition to slavery increased through political actions along with mass rebellion, the British parliament would pass the Slave Act of 1788 and Amelioration Act of 1798 related to the treatment of Africans in bondage under the control of England. Later in 1807, the British parliament would pass the Slave Trade Act, ostensibly outlawing the transatlantic trade. The trade would continue illegally and the domestic production and trade in enslaved Africans satisfied the demands for unpaid labour within the growing cotton plantations of the southern United States. Later in 1833 the Slavery Abolition Act was passed by the British parliament. Nevertheless, Africans in the Caribbean were forced to undergo a period of apprenticeship leading to years more of virtual enslavement and consequent rebellion.

Other events such as the Haitian Revolution against France from 1791-1803 resulted in the founding of a Black Republic in the Caribbean, heightened the fears of the slave owning class, which maintained its political advantage through the American legislative system. It would take a series of slave rebellions in the United States from 1800 through 1859 to escalate the intransigence of the planters provoking their secessionist ambitions leading to a civil war from 1861-1865, which created the conditions for the legal abolition of African slavery in the United States. [[ix]]

The legacy of slavery extends into the 21st century

African American historian Gerald Horne published a study on the impact of the anti-slavery movement in Britain and the motivations for independence by the founders of the United States during the late 18th century. The book entitled: “The Counter-revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America”, advances a thesis which conflicts with the conventional assumptions fostered by the educational system related to the separation of the 13 colonies from Britain.

An abstract of the Horne research project released in 2014 says: “Prior to 1776, anti-slavery sentiments were deepening throughout Britain and in the Caribbean, rebellious Africans were in revolt. For European colonists in America, the major threat to their security was a foreign invasion combined with an insurrection of the enslaved. It was a real and threatening possibility that London would impose abolition throughout the colonies—a possibility the founding fathers feared would bring slave rebellions to their shores. To forestall it, they went to war.”[[x]]

154 years since the legal abolition of involuntary servitude in the United States, the descendants of Africans formerly enslaved are still facing national oppression and economic exploitation. Today the criminal justice structures serve as the principal mechanism of social containment and institutional repression. Inevitably it will take a revolutionary struggle to complete the genuine emancipation of the African people in America.

* Abayomi Azikiwe is Editor at Pan-African News Wire

Endnotes

[i]https://www.theroot.com/three-fifths-clause-why-its-taint-persists-1790895387accessed 24 February 2019

[ii]http://www.ouramericanrevolution.org/index.cfm/page/view/m0149accessed 24 February 2019

[iii]http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/rights/slave_free.htmaccessed 24 February 2019

[iv]https://www.britannica.com/biography/Granville-Sharpaccessed 24 February 2019

[v]http://abolition.e2bn.org/people_25.htmlaccessed 24 February 2019

[vi]https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/zong-massacre-1781/accessed 24 February 2019

[vii]https://face2faceafrica.com/article/sons-of-africa-the-early-political-group-formed-in-the-1700s-by-freed-slaves-in-londonaccessed 24 February 2019

[viii]http://abolition.e2bn.org/people_26.htmlaccessed 24 February 2019

[ix]https://www.questia.com/library/7253938/american-negro-slave-revoltsaccessed 24 February 2019

[x]https://nyupress.org/books/9781479893409/accessed 24 February 2019