Philanthropy, of various forms and origin, occupies a central, well-accepted position in the nations of Africa today. Invoking an historic confrontation between the supporters and opponents of Rag Day at the University of Dar es Salaam, this article presents a radical critique of such philanthropy. Though it occurred in 1968, the contrasting attitudes towards charity it depicts are of primary importance for the realisation of genuine social and economic progress in Africa today.

Philanthropy

Aid (philanthropy, foreign aid, charity) dominates life in Africa. All aspects of society are penetrated by the non-governmental organisation (NGO) culture. Numbering in the hundreds, these groups deal with a myriad of causes ranging from supporting street and disabled children, assisting persons with HIV infection, empowering women and girls, improving education and health services, giving free legal service to the poor, supporting marginalised communities, and providing health education to promoting civil rights and media freedom.

The existence of NGOs is seen as a natural state of affairs. In these days of high unemployment, young people, especially university graduates, are keen to land a job with an NGO. University professors and other experts yearn for consultancy assignments with them, as they need little effort and are quite lucrative. One takes part in the activities of this or that NGO not because one believes in the cause but because of the benefits it confers. The NGOs, which function in a fragmented manner, get their funds mostly from Western nations, United Nations agencies, international organisations and individual donations. In addition, most African nations are highly dependent on external funding in the form of grants and soft loans as well as foreign investments.

On the domestic front, fund raising activities for schools, health clinics, disabled children, people with Albinism, people affected by natural disasters and a host of other causes occur on a regular basis. Newspapers regularly feature stories of politicians and ministers soliciting donations for schools; banks, mining companies and other firms building classrooms and donating educational supplies; religious bodies urging their followers to cater for the needy on special occasions; wealthy individuals visiting shelters for people with special needs; office workers participating in fund raising walks to help children with disabilities, and so on.

Those who are better off should assist those who have been left behind to ensure that the benefits of economic progress are shared among all members of society, locally and globally. This spirit, which pervades these charitable activities, is commonly accepted by the providers and recipients, and permeates our national fabric, internally and at the international level. I call it the humanitarian spirit.

Yet, others disapprove. Conservatives proclaim that regular assistance to the poor and needy, especially by state bodies, only makes things worse. The poor have been left behind because they avoid hard work and sacrifice. Automatic handouts make them lazier and drive them towards anti-social conduct.

The progressives, for their part, declare that the poor need jobs and investments, and provision of the right kind of training to meet the challenges of modern life, not just charity, public or private. On the international front, they say that aid should be supplanted by trade and investments from abroad. That is the only way to raise living standards in the poor nations.

There is, however, a fourth spirit towards charity, which I denote the radical spirit, which differs in a critical manner from these three spirits. But it is now largely forgotten, in Africa as elsewhere, even though it had begun to gain prominence in the 1960s and 1970s.

The aim of this article is to illuminate the nature of the radical critique of philanthropy through an extended discussion of an event that occurred in 1968 at the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. I hold that it is only the radical approach and not any of the other three that can lift Africa and its people out of the state of underdevelopment and mass poverty. And this event from history shows how it was manifested in concrete terms.

Rag Day

On this Saturday, the 9th of November 1968, a cool breeze blows on the hilly campus of the University College, Dar es Salaam. With no lectures today, the place remains sleepy. Though, there is a major exception: some 300 students, nearly a quarter of the student body, are wide-awake by 6 am and stand at the cafeteria door as it opens for breakfast. From their attire and demeanour, it is apparent that they do not form a unified group. The majority have put on torn or funny looking clothes while those in a smaller sub-group, about a tenth of the total, are dressed as students here usually do. The two groups also have contrasting intentions. The former are set to embark on a festive, seemingly virtuous course of action while the latter have a plan to sabotage, in a decisive way, these festivities.

I refer to Rag Day, by now an established and much anticipated annual event at this campus. It is a day set aside for the students to raise funds for a worthy charitable cause. They do so by marching through city streets, a tin in hand, to solicit donations from passers-by and merchants. Dressed in tattered clothing or clownish costumes, they shout, sing, bang their tin cans, dance here and there, as they beg for money. It is for a good cause, they say. And they have official sanction, from the city offices and the university administration. The latter also provides the vehicles that transport them to and from the city centre.

Before examining what transpired at this campus on that fateful day, let us first look at the general history of Rag Day.

Origin and essence

The wiki-dictionary, (en.wiktionary.org), defines Rag Day as a day on which “university students do silly things for charity.” It appears to have originated in England in the later part of the 19th century. The name stems not so much from the rags adorned by the students but by their tendency to rag (hassle, pester) members of the public in the process of eliciting money from them.

By the 1960s, Rag Day was a regular event in universities across Britain and some other parts of the world. The first Rag Day in Africa was held at the University of Pretoria, South Africa, in 1925. After the former British colonies gained independence and established their own universities, they too began to hold Rag Day.

Rag Day continues to be staged at many universities today. At times, it occurs during a larger event called Rag Week. Although the manner in which it unfolds varies from place to place, the essence is the same, to raise funds for charity. In the United Kingdom, annual funds raised during Rag Day are estimated to range from five to ten million pounds. At the University of Pretoria, South Africa, Rag Day is staged with musical and other festive events and raises funds that are allotted to about 200 charities. Other means besides street marches are also used for this event. In Singapore, Rag Day is at times enjoined with major national celebrations (National University of Singapore 2011; Orr 2012; University of Pretoria 2012).

In the past, Rag Day was associated with rowdy, drunken, disorderly and anti-authoritarian behaviour by the students. This type of conduct seems to have been brought under control in most places and Rag Day has gained more respectability from the public. Some universities in Nigeria, though, present an exception. Their students tend to be quite unruly. Many dress in a shocking style. Allegations are rife that instead of being channelled to charity, the money they raise is pocketed by themselves (Buzznigeria 2018; EduAfrica 2015).

Yet, in Africa today, Rag Day persists only in a few nations. In several places, it died a natural death. It is only at University of Dar es Salaam that it died a sudden death. And that happened not due to an edict issued by an authority but stemmed from a defiant act on the part of that smaller of group of students.

It is to the story of the why and how of the undoing of Rag Day at this university that I turn to. My aim is to show that this story demonstrates distinctive attitudes towards charity that are of central relevance to the issues relating to the economic and social development of African nations today.

The undoing of Rag Day

We return to 1968. Rag Day at the Dar es Salaam campus is organised by the Tanzania chapter of the World University Service (WUS). In the week preceding the event, cyclostyled posters advertising the event are pinned on all noticeboards:

*********

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE RAG DAY HARK! W.U.S. IS SPEAKING!

The World University Service (Tanzania) Committee has sought and obtained permission to hold a RAG DAY on Saturday, 9 November 1968.

The event will consist of a fund-raising procession for the benefit of the Msimbazi Children’s Centre. Some students will adorn and ride floats, while others will solicit offerings from embassies, government offices and business concerns along the route.

Departure: Opposite the Cafeteria at 7.30 a.m., on busses and lorries.

Itinerary: Upanga Road, Jamhuri St, Uhuru St. to the Cloak Tower, Independence Avenue to the Askari Monument, Azikwe St., City Drive, Shaban Roberts St., Independence Avenue back to the Askari Monument, Makunganya St., India St., Upanga Road back to the University College.

STAFF STAFF STAFF STAFF STAFF STAFF

University College Staff will be visited in their offices and at their homes on the previous day, Friday. Please note: paper money is easier to handle.

STUDENTS STUDENTS STUDENTS STUDENTS

At least 150 students are required to carry out this good work. Sign up IN THE COMMON ROOM OF YOUR HALL so that you will find place in one of the vehicles, which is [?] provided for transport, and be PUNCTUAL on Saturday morning. The more, the merrier!

Dress in RAGS of every colour and description! Rehearse your calls and songs! Plenty of noise is required!

Nametags and tin cans will be provided to collectors.

Only twenty percent of the proceedings [?] will be retained to cover incidental expenses and to promote other worthy causes.

EIGHTY PERCENT GOES TO MSIMBAZI.

********

An interview with WUS (Tanzania) chairman, S. Amos Wako (a student from Kenya, later to become the Attorney General of that nation), is prominently featured in the student magazine, The University Echo:

Wako stated that the “Rag” celebration was an important event in most universities of the world. It had two aims one, to provide room for relaxation for the students, staff and administrators, and the other to raise funds, 80 percent of which went to the needy, he said.

Wako stated: “The World University Service believes, as its name implies, that the university should serve the community in which it is created,” The Standard(1968a).

This promotion of Rag Day does not sit well with a small group of radical students organised under the umbrella of the University Students’ African Revolutionary Front (USARF) and/or the campus branch of the youth wing of the ruling party, TANU [Tanganyika African national Union] Youth League (TYL). In the evening before the event, USARF holds a meeting in which Rag Day is the sole topic on the agenda. After an extended debate, they resolve in unison that it is not compatible with African culture and the desire of Tanzania to build a society based on socialism. Rag Day needs to be stopped, one way or another.

No wonder, in the morning of Rag Day, they are the first ones at the cafeteria door. After the meal, they head to the parking area nearby where the vehicles that will transport the Raggers stand. They gather chairs, wooden logs, dustbins and other things to erect a makeshift barrier at the exit of the parking lot.

A few set about deflating the tires of the parked vehicles by letting out air. One has a sharp pocket knife, which he uses to puncture one tire of a mini-bus. The drivers of these vehicles, who are gathered in a corner of the parking lot, do not intervene or say anything. Having done their deed, the radicals stand in a defiant mood in front of the barrier.

My memory has it that these anti-Raggers included Jonathan Kamala, Andrew Shija, Bernard Mbakileki, Ally Mchumo, Salim Msoma, Ramadhan Meghji, Issa Shivji, Karim Hirji, Charles Kileo, S Mdundo, J Moronda (Tanzania), Yoweri Museveni, Eriya Kategaya, J(?) Wapakabulo (Uganda), Kapote Mwakasungura (Malawi) and Kabiru Kinyanjui (Kenya).

As the Raggers enter the parking area, they are in for a shock. Their vehicles cannot move; the exit is blocked by a human and a physical barrier. An extended confrontation between the two sides ensues. But it is all a verbal exchange; there is no physical contact or violence. The Dean of Students appears on the scene about an hour later. His attempt to make the radicals stand down is met with deaf ears. Though he can order the campus guard to dismantle the barrier, he is in two moods about it. On the one hand, he opposes what the radical students have done. On the other hand, he fears the political consequences if he acts harshly against them. After all, these defiant fellows are shouting in the name of the official policy of socialism, and he may be seen as an opponent of that policy.

A short while later, two vehicles with armed policemen descend at the site of the fracas. Their commander tells the radical students to move aside so that the barrier can be removed. But they remain defiant. Andrew Shija, the TYL chairman, is bold enough to lecture him about the Arusha Declaration and why Rag Day is incompatible with the policy of Socialism and Self-Reliance. Like the Dean of Students, he is unsure about how to deal with the situation. His training tells him that he should arrest these troublemakers and remove the barrier by force. But what will his superiors think? Will be accused of violating the national policy?

Reluctantly, he comes to a decision. There is a threat of public disorder here, he says. Rag Day is suspended. The stunned Raggers have no recourse but to return to their halls of residence. Fearing further defiance from the radicals, the Dean of Students also cancels the Rag Day dance party that was to be held that evening. It is a total victory for the Radical students in that after this day, no Rag Day was ever celebrated at this campus.

When land was requisitioned for the university campus, it came with a large cashew nut farm (shamba) on the outskirts. This area lies undeveloped and the farm shows signs of years of neglect. Of recent, USARF/TYL members have started working at the shambaduring weekends. It is a purely voluntary effort, clearing weeds and overgrowth, and harvesting the ripe nuts. The proceeds from the sales are donated to the African Liberation Committee based in Dar es Salaam. In the aftermath of the Rag Day debacle, USARF/TYL invites all members of the university community to participate in this and similar efforts. The funds raised could also be sent to the needy children’s centre in the city.

To help others, students should show serious commitment by engaging in on-going practical work rather than just begging in the streets once a year, they declare.

It has to be noted that the radicals stood against Rag Day without seeking approval from any authority, on the campus or beyond. It was a risky decision as we could have faced serious disciplinary action from the administration or even arrest by the police. We stood for our principles and were saved by the prevailing spirit of socialism in the nation and not by any person in high authority.

Pros and cons

During the next two weeks, the controversy about Rag Day and its demise takes centre stage at the campus and in the national print media. Most students, academic staff and administrators oppose the action of the radicals. While the official media maintain a discrete silence on the matter, the main (British owned) English language daily (The Standard) pens a strongly worded editorial that castigates the radical students. It depicts them as political saboteurs who lack concern for the plight of disadvantaged children. These two weeks feature a lively but heated exchange between the two sides in the Reader’s Forum section of this paper. To its credit, despite its editorial stand, the paper gives adequate space to both sides on this page. Thus, the issue of 17 November 1968 has four letters, two for each side. The longest letter gives a militantly worded defence by USARF chairman, Yoweri Museveni.

The principal points presented by those who support Rag Day are:

- The Raggers are motivated by a desire to help needy children.

- There is nothing wrong if they also have fun in the process.

- The radicals are a bunch of ideologically blinded, self-serving political opportunists.

- Instead of mounting their dramatic action, they should have worked with the organisers of Rag Day and reached a compromise acceptable to both sides.

- Moreover, they have been misled by a few foreigners with no concern for the people of Tanzania.

The last accusation is ironic: It is made by students who are themselves not Tanzanians and it is not pointed out that WUS, the Rag Day organising group, is a foreign funded entity whose local chairman, moreover, hails from Kenya. While WUS officials receive financial support from abroad, USARF has no internal or external funder.

In any case, such nationalistic proclamations are a ruse to divert attention from the main issue. Being a part of the young University of East Africa, this campus has students and staff drawn from many nations. USARF/TYL members know that no nation or race has a monopoly over good or bad conduct.

The arguments advanced by the radical students and their few supporters among the academic staff note the following points:

- USARF/TYL members support the provision of assistance to needy children.

- But that assistance should be provided by the rest of the society as a matter of right and not in the form of occasional handouts by the privileged.

- And it should certainly not be done in a way that makes a mockery of the destitute children.

- The main long term aim should be to struggle to eliminate poverty, not just throw crumbs to the poor occasionally.

- Charitable actions like Rag Day actually serve to underpin an unjust and unequal social system by providing a safety valve to release the built up pressure, and give legitimacy to those who have amassed ill-gotten gains.

The case for the radical side is cogently summarised by Andrew Lyall, a law lecturer, in a letter to The Standard. It is reproduced in full below.

If socialism is an attitude of mind, it is clearly an attitude which editorial writers, in spite of their nominal adherence to national policy, are totally unable to comprehend. Your leader on “Rag Day” leaves this beyond doubt.

Charity has a necessary function in Western countries only because of the defects of the capitalist system. Socialism certainly does not preclude charity. If we are interested in making the lives of the Msimbazi children not merely “a little more comfortable, a little brighter” but in solving the problem, that will not be done by people dropping a few shillings in a tin. It serves only to indulge the hypocritical emotions and deepen the hypocrisy of those whose concern for the plight of the orphans goes so far as the change in their pocket, but stops short of any policy that would make a real impact on their standard of living.

To be an orphan is to feel left out of society, a feeling that is increased not lessened by receiving donations from charity. The children of Msimbazi need to be adopted by the nation, to feel that everyone is their father.

If existing Government funds are not sufficient to solve the problem, one does not have to look far to find additional sources. The more fortunate members of society will have to become somewhat less fortunate.

Your statement “it is not shameful to wear rags to solicit funds from others” misses the point. It is not shameful to wear rags if that is all you have to wear. But for others to put them on as fancy dress for a carnival when they are surrounded by those for whom they are, of necessity, daily wear displays at the very least gross insensitivity to their feelings.

The children of Msimbazi have their dignity too. It is not to be insulted by patronising handouts from the “fortunate”. Nor should attempts be made to divert revolutionary students from their purpose by a squalid appeal to bourgeois sentimentality.

Andrew Lyall

University College, Dar es Salaam

The Standard (1968b).

In advancing these views, USARF/TYL stood together with the eminent United States civil rights leader, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

“True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar; it comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring,” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Who won?

Did the action taken by the radical exercise a long term impact? – That is the question of the day. And the answer is a resounding “no”. While that battle of 1968 was won by USARF/TYL, looking around Africa today, it is abundantly clear that the supporters of Rag Day have prevailed in the long run. Even in Tanzania, where no Rag Days are held, the spirit enshrined in Rag Day has taken a firm hold among the youth, the intelligentsia and the political establishment.

The punitive conservative spirit, which blames the poor for their own predicament makes itself felt now and then, as when the authorities round up beggars and street children and repatriate them to their home villages. Some voices in the media concur with such actions (Mwita 2010). But they have a limited focus, and do not affect the prevalence of the patronising Rag Day type of spirit in the social fabric as a whole.

On the other hand, the socialistic spirit whereby people would join hands in mutual solidarity to construct a society founded on the principles of social justice and equality, where adequate nutrition, good housing, clothing, appropriate health care and education are enshrined and implemented as basic human rights, where people with disabilities and special needs do not require handouts but are taken care of by the state, where grassroots democracy prevails, and where the people of Africa stand on their own feet, and not be dependent on the crumbs from external entities, sadly that spirit has waned considerably.

The ethic of capitalism and neoliberalism has triumphed and the continent continues to be highly dependent on largess from the so-called donor nations and institutions. To members of USARF, begging was an affront to human dignity. Yet today our leaders are perpetually standing in front of the “donors”, with their hands outstretched without any sense of shame.

An example: Former President Jakaya Kikwete of Tanzania proudly declared in October 2010 that he was the first leader from Africa to gain an audience with the United States President Obama. He went on to say with elation that President Obama had promised to “flood our nation with assistance” (Mwendapole and John 2010). Earlier, after being criticised for making too many trips abroad and that with a large contingent, he had defended himself by claiming that it was because of his trips that the previous United States president George Bush had promised to give sufficient mosquito-protecting bed nets to cover the needs of each and every Tanzanian child.

The economic policies of African nations are geared towards attracting external funds on a continuous basis, thus further entrenching the tentacles of dependency, which extends to all facets of society, agriculture, industry, transport, education, health, media, culture and political organisation. External elements lay down how things should be for us in all the aspects of our lives. Once in a while, an NGO finds itself in trouble with the state authority. Yet, it is always a transient situation and has no effect on the NGO culture as a whole.

Walter Rodney has noted that a basic feature of economic development is the enhancement of the ability of a people to determine their own lives. It is in that respect we can say that despite a modicum of economic growth, Africa has become more and not less underdeveloped over the past three decades. The little industrial capacity built up after independence was dismantled as a result of the neo-liberal onslaught. Thus, Tanzania is one of the world’s largest producers and exporters of cashew nuts. But the nuts are exported in raw form as almost all of its cashew nut processing factories have been idled after privatisation. It has as well not developed any capacity to extract the valuable oils and chemicals from these nuts. And many such examples can be given.

The attitude towards aid and charity has been transformed among all segments of the society. Instead of confidence to chart our own path, attitudes of submissiveness and meekness towards outsiders prevail (John 2010). An announcement of the possibility of getting a large basket of foreign funds is portrayed in the private and state media in exaggerated and celebratory terms. For instance, the Nipashe Special Supplement (2010) depicts a large agricultural assistance loan from India as the grand saviour of the Tanzanian farmer. Yet, today, that prediction remains so far from being a reality that no one talks about it anymore.

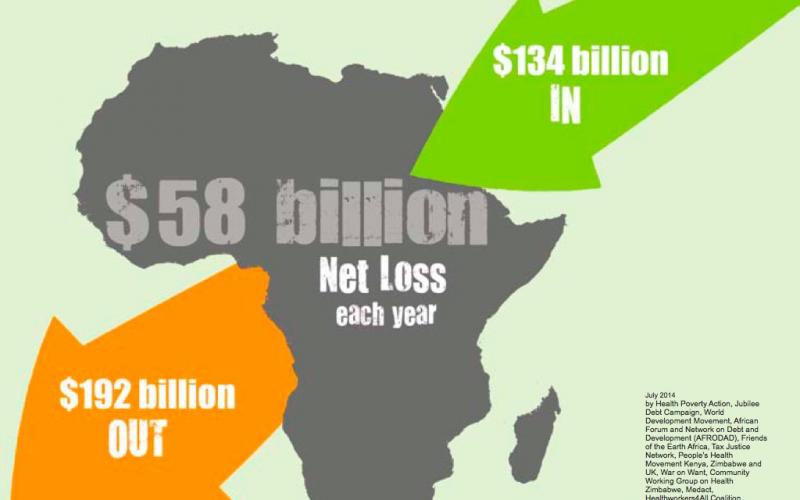

In reality, such loans and grants are a means for the external powers to secure a greater economic foothold and market for their companies, gain lucrative investment opportunities and enhance their image, especially in this era of a highly competitive climate between China and the West. And the “aid” always damages the capacity of African nations to determine their own destiny.

Aid has never been just about helping people. It is also realistically about gaining influence in the world and exercising soft power. Providing aid money can generate valuable access and generate a sympathetic cohort of people who can be called upon to further down the line, Cheeseman (2019).

A large volume of literature documenting the deleterious effects of foreign “aid” exists. The pioneering work of Hayter (1971) depicts its structural impact while Hancock (1994) provides illuminating cases that demonstrate the fundamentally flawed nature of “aid” projects. Of the many other works of relevance, I note a few: Bah (2014), Barker (2017), Caufield (1997), Chery (2012), Hudson (2003), Lagan (2018), Moseley (2015), Nyikal (2005), Polman (2011) and Serumaga (2017).

Even the devoted promoters of foreign “aid” proclaim that it is of major benefit to the providing nations (Cheeseman 2019, Gates 2017).

A more stable world is good for everyone. But there are other ways that aid benefits Americans in particular. It strengthens markets for United States goods: of our top 15 trade partners, 11 are former aid recipients. It is also visible proof of America’s global leadership. Popular support for the United States is high in Africa, where aid has such a dramatic impact, Bill Gates (2017)

As such actuality is hidden by the mass media, people in most of the recipient nations, especially in Africa, regard the “aid” as a heavenly blessing. More than half a century after attaining political independence, the majority in most African states live under insecure and substandard economic conditions. The small scale farmers remain at the mercy of a volatile external market while the urban dwellers, even the educated ones, find it extraordinarily difficult to land a reasonable, permanent job and try to eke out a living from a very competitive petty and unreliable small-scale trading environment.

The blame for Africa’s predicament is placed wholly and solely on the shoulders of its corrupt leaders, past and present. People say that the out of goodwill, “donors” from outside have poured hundreds of millions of dollars into Africa. But instead of utilising them for the benefit of the nation these leaders squandered them for their own benefit or used them in inappropriate and inefficient ways.

Yet, it is forgotten that these “donors”, like the World Bank, the United Nations agencies, the bilateral “aid” agencies of the Western nations and other organisations have been with Africa since the first days of independence. They have been centrally involved in policy making and determination of the type of economic projects. And they have little to show in terms of having made a major long run difference in Africa but much to show in terms of how their nations and organisations have benefitted. If there is blame to be placed, they deserve at least half of it. Further, hardly anything is said about the havoc created on the continent by the myriad of external military “assistance” programmes.

The NGOs often have “experts” from the “donor” nations who lack qualifications and experience for the tasks involved, and who come to Africa to ease their conscience. Their intentions notwithstanding, they live in exclusive compounds, enjoy the tropical holiday and accumulate good sums to fund a mortgage back home. Yet, the ordinary people, officials and intellectuals here treat them as if they are demi-gods – they are the bearers of the mighty dollar. What ensues is a progressive cycle of dependency, denigration of our own experts and expertise, self-recrimination and loss of confidence (Hirji 2007; John 2010; The Citizen Reporter2010).

Such attitudes are reminiscent of the attitudes towards the rich and charity among the working people of Britain that were aptly captured by Robert Tressel a century ago (Tressel 1914; 2012). They were resigned to whatever fate held in store for them, and rejected any talk of alternative to the existing state of affairs.

System change not charity

Charity, aid or philanthropy at the international and domestic levels, despite the stated intentions of the providers, serves an essential long-term purpose. It provides legitimacy to an unjust and exploitative socio-economic system. It functions like a pressure release valve of steam engine, preventing explosive occurrences and permitting the multi-million dollar beneficiaries to continue their economic stranglehold over the masses (Iqbal 2019; Moloo 2018; Moseley 2015; Todhunter 2012).

Even the talk about giving jobs to the poor or focusing on trade and investments for poor nations misses the mark. First, neo-liberal capitalism thrives on low wages and needs a large class of unemployed or semi-employed people. Second, the types of trade and investment opportunities offered to poor nations are meant to extract resources and economic surplus from them and enhance their dependence on external forces.

Meaningful African liberation requires a decisive severance of the bonds of material and intellectual dependency. And, in that matter, an essential point must be stated with clarity. Although one talks of “them” and “us”, it should be understood, as the radicals of the earlier era did, that the question is not that one of race or skin colour. It is one of basic economic structures, international and national; of class relations and social systems. Africa needs system change, not charity (Hirji 2017; Rodney 1971).

African liberation has to be founded on three basic principles: socialism, regional cooperation and regional self-reliance. Instead of being mired in seeking solutions within the confines of the current neo-liberal system, African youth must have bold dreams and think in terms of a fundamental transformation that goes beyond this system (Tandon 2019). That was the vision of the radicals of the earlier era, and it is a vision that the youth of today must adopt.

The technological capacity to resolve all the critical problems facing humanity had been present at least for half a century. But it is the strangle-hold of the rich and powerful classes and nations over the state, politics, media and thought process that have prevented that capacity from being utilised for that purpose (King 2010; Sunkara 2019).

The actions of USARF/TYL in that era were founded upon their concurrence with the vision of the great American civil rights champion: “The time has come for us to civilise ourselves by the total, direct and immediate abolition of poverty, “ML King (2010).

Let this be the cry of the African youth of today as well. For, the future of Africa and indeed, of humanity, lies not with the modern day do-gooders – the NGOs, local and external philanthropists, “aid” donors and their employees but with those who will boldly mobilise and organise the masses for a fundamental transformation of the neoliberal, capitalist economic system.

* Karim F Hirji is a Professor of Medical Statistics (retired) and Fellow, Tanzania Academy of Sciences.

References

Bah CAM (2014) Neocolonialism in West Africa: A Collection of Essays and Articles, iUniverse, https://www.iuniverse.com/

Barker M (2017) Under the Mask of Philanthropy, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (18 February 2017)

Buzznigeria (2018) Origin and Meaning of Rag day for Nigerian Universities, https://buzznigeria.com/origin-meaning-rag-day-nigerian-universities/accessed 5 February 2019

Caufield C (1997) Masters of Illusion: The World Bank and the Poverty of Nations, Henry Holt & Co, New York.

Cheeseman N (2019) Why There’s a Case for Aid to Dictatorships, The Citizen (Tanzania) 16 January 2019.

Chery D (2012) USAID: The Soft Arm of Imperialism, News Junkie Post, 24 November 2012, http://newsjunkiepost.com/2012/11/24/usaid-the-soft-arm-of-imperialism/

EduAfrica (2015) Why Students Re-Invent Rag Day for Their Personal Gain, http://www.edufrica.com/2015/10/photo-speaks-why-students-re-invent-rag-day-for-their-personal-gain/

Gates B (2017) How Foreign Aid Helps Americans, Gates Notes, www.gatesnotes.com/Development/How-Foreign-Aid-Helps-mericans, 17 March 2017

Hancock G (1994) Lords of Poverty, Grove Press/Atlantic Monthly Press, London and New York.

Hayter T (1971) Aid as Imperialism, Pelican Books, UK.

Hirji KF (2007) Questioning Assumptions (HakiElimu Column), The Citizen (Tanzania), April 2007.

Hirji KF (2017) The Enduring Relevance of Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Daraja Press, Montreal, Canada.

Hudson M (2003) Super Imperialism: The Origin and Fundamentals of U.S. World Dominance, Pluto Press, Boston.

Iqbal N (2019) Woke Washing? How Brands like Gillette Turn Profits by Creating a Conscience, The Guardian, 21 January 2019, www.theguardian.com/media/2019/jan/19/gillette-ad-campaign-woke-advertis... accessed 5 February 2019

John D (2010) Foreign Science Teachers Can Boost Students’ Performance, The Citizen (Tanzania), 12 September 2010.

King ML (1965) Martin Luther King Quotes, www.goodreads.com/ quotes/19814

King ML (2010) Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? Beacon Press, Boston.

Langan M (2018) Neo-Colonialism and the Poverty of 'Development' in Africa, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Moloo Z (2018) The Problem With Capitalist Philanthropy, Catalyst, 2 June 2018.

Moseley WG (2015) The Dark Alliance of Global Philanthropy and Capitalism, Al Jazeera (www.aljazeera.com), 1 Dec 2015.

Mwendapole J and John E (2010) Kikwete: Obama Kuimwagia Misaada Tanzania, Nipahse, 3 October 2010.

Mwita P (2010) It Is Time Beggars Were Prosecuted, Sunday News (Tanzania), 7 November 2010.

National University of Singapore (2011) NUSSU Rag Day 2011 to Join Singapore in Celebrating National Day, http://newshub.nus.edu.sg/ pressrel/1104/130411.php

Nipashe Special Supplement (2010) Mabilioni Ya India Kunufaisha Wakulima Tanzania, Nipashe, 5 November 2010.

Nyikal H (2005) Neo-Colonialism In Africa: The Economic Crisis In Africa And The Propagation Of The Status Quo By The World Bank/IMF And WTO, https://web.stanford.edu/class/e297a/Neo-Colonialism%20in %20Africa.pdf

Orr G (2012) Bad Behavior That's All in a Good Cause: Students are Carrying on the RAG Tradition, http://www.independent.co.uk/ news/education/higher/bad-behaviour-thats-all-in-a-good-cause-tudents-are-carrying-on-the-rag-tradition-6298083.html, 2 February 2012.

Paget KM (2015) Patriotic Betrayal: The Inside Story of the CIA’s Secret Campaign to Enroll American Students in the Crusade Against Communism, Yale University Press.

Polman LS (2011) War Games: The Story of Aid And War In Modern Times, Viking, London.

Rodney W (2011) How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (third edition), Pambazuka Press, Oxford; CODESRIA, Dakar; Black Classic Press, Baltimore; and Walter Rodney Foundation, Atlanta.

Serumaga M (2017) Hunger, Foreign Debt and Uganda’s Fairytale Budgets, Pambazuka News, 7 December 2017, www.pambazuka.org/democracy-governance/hunger-foreign-debt-and-uganda%E2%80%99s-fairytale-budgets accessed 5 February 2019

Sunkara B (2019) Martin Luther King was no Prophet of Unity. He was a Radical, The Guardian, 21 January 2019, www.theguardian.com/ commentisfree/2019/jan/21/ martin-luther-king-jr-day-legacy-radical accessed 5 February 2019

Tandon Y (2019) 2019: A Year of Revolutionary Rupture? Looking Beyond the Curve, Pambazuka News, 15 January 2019, www.pambazuka.org/global-south/2019-year-revolutionary-rupture-looking-beyond-curveaccessed 5 February 2019

The Citizen Reporter (2010) Donors: Why Dar Suffers Huge Deficit, The Citizen (Tanzania), 7 December 2010.

The Standard (1968a) College T.Y.L. Cancels `Rag Day, The Standard (Tanzania), 10 November 1968.

The Standard (1968b) Reader’s Forum: The Sabotaging of Rag Day, The Standard (Tanzania), 17 November 1968.

Thompson MA (1982) Unofficial Ambassadors: The Story of International Student Service, International Student Service

Todhunter C (2012) Dollar Billionaires in Poor Countries: India’s “Philantrocapitalism” Global Research, Global Research, September 10, 2012, http://www.globalresearch.ca/dollar-billionaires-in-poor-countries-indias-philantrocapitalism/

Tressel R (1914; 2012) The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists, Wordsworth Classics, London.

University of Pretoria (2012), Rag Day, http://web.up.ac.za/ default.asp?ipkCategoryID=7688

Wikipedia (2018) Rag (Student Society), en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/ RAG_(Student_society)

Wikipedia (2019) World University Service, https://en.wikipedia.org/ w/index.php?title=World_University_Service&oldid=812574376

- Log in to post comments

- 5006 reads