The second quarter of 2018 has seen South Africa register a negative growth designated recession while the country’s currency, the rand, continues to be volatile.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa has said that the technical recession announced inside the country and internationally is only a transitional phase.

The ruling African National Congress (ANC) leader and head of state will be standing for elections in less than one year. Reports of an economic slump are being utilised by the opposition to cast aspersions on the continent’s oldest liberation movement turned political party.

Ramaphosa came into office from the deputy presidency with the resignation of former ANC leader and President Jacob Zuma in February. Both the domestic opposition to Zuma in and outside the ruling party, along with international interests, attributed the slump in economic performance prior to early 2018 to the atmosphere generated by allegations of corruption against the former president.

With the assumption of the presidency by Ramaphosa the leading economic indicators improved. Nonetheless, Ramaphosa, a co-founder and former Secretary General of the National Union of Mineworkers, a leading affiliate of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), sought to create an image that the political situation was stabilised and ripe for foreign investment. Ramaphosa knew that he had to unite the ANC internally and reinforce the strained relations between the ruling party and its allies within COSATU, the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the South African National Civic Organisations (SANCO).

Yet other long standing issues require addressing before the ANC can rest assured of not only recapturing the presidency and parliament in 2019, notwithstanding on a level which is approaching a two-thirds majority. Opposition parties remain far behind while the alliance of convenience between the right-wing Democratic Alliance and the putative “left” Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) appears to have imploded. [[i]]

A resolution passed jointly from the EFF and the ANC by the National Assembly in late February called for the seizure of European settler-owned land absent of compensation. White farmers became nervous about the prospects of losing their ill-gotten wealth. This is obviously a key element in the recessionary spiral, which is dominating the political landscape.

Statistics South Africa reported on 4 September that there was 0.7 percent negative growth in the second quarter of 2018. In addition, a revised assessment of performance in the first quarter was placed at a 2.7 percent contraction.

A recession under capitalism is declared when there is two consecutive quarters of negative growth within the national economy. Other aspects of the malaise are manifested through the more than 27 percent official unemployment rate in South Africa.

In the agricultural industry production fell by 29.2 percent in the second quarter right after an even larger drop of 33.6 in the first quarter. The causes behind this decline is said to be resulting from crop failures due to drought in the Western Cape and a hailstorm in Mpumalanga.

On 5 September the value of the South African rand also went down with the realisation of a renewed recession, said to be the first one since 2009. However, and surprising to many, there was a slight rebound by the following day with one rand being equal to US $0.065 in United States dollars as financial publications said that the South African currency was too undervalued.

South African currency, the rand. Credit: South African Reserve bank

South African Business Live online publication noted in a report about the currency situation that: “The rand enjoyed something of a reprieve in mid-morning trade on Thursday (6 September), strengthening slightly against the dollar while government borrowing costs climbed down from nine-month highs. The relief rally in local assets coincided with the Moody’s report, noting that South Africa is in a technical recession. The weaker-than-expected economic performance adds to the fiscal and monetary policy challenges posed by the 20 percent depreciation of the rand against the dollar so far this year, the ratings agency said in a statement.” (6 September)

Who controls South Africa?

The country became a key player in the supply of strategic minerals and other natural resources during the late 19th and 20th centuries. Even today there are some of the world’s largest reserves of gold, platinum, iron ore and coal in South Africa.

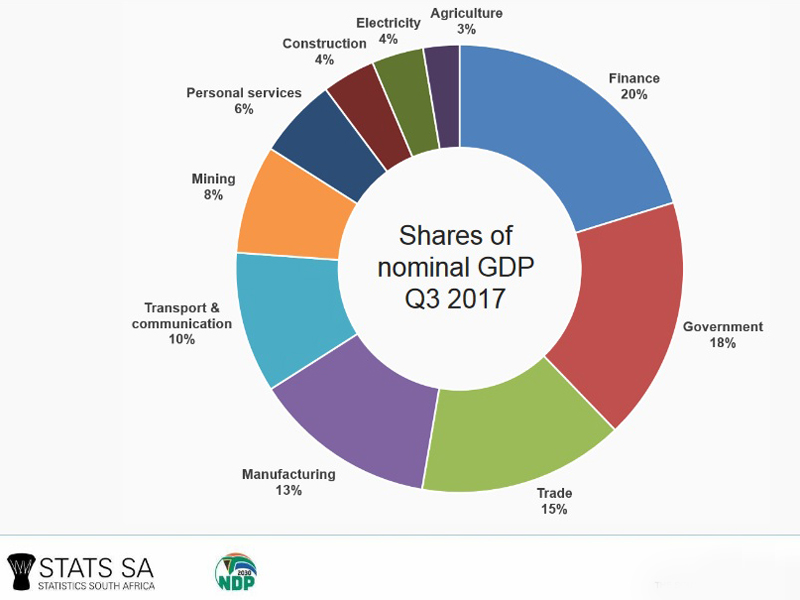

However, within a national context, mining constitutes less than 7 percent of the economic output down from 21 percent during the 1970s. Mine owners point to lower prices and rising production costs for the problems within the industry.

Since the 1990s, the economy has been dominated by the tertiary sector including wholesale and retail trade, tourism and communications, constituting 65 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP). Statistics South Africa reveals that 20 percent of the economy is held by the financial sector.

South African economy by proportion of sectors in 2017. Credit: Statistics South Africa

It is the financial sector as well, which is facing significant challenges. One firm, which analyses the banking industry, explained that in recent years there has been decline in performance that has clearly contributed to the economic crisis.

Consultancy.co.za reported earlier in 2018 saying: “The slump in South Africa’s GDP has affected most sectors of the country’s economy, but perhaps none more so than the banking sector. A new report from global professional services firm EY reveals that banking revenues in South Africa are currently growing at their slowest rate since the Global Financial Crisis.” (19 March)

This same article goes on further to emphasise: “The country’s banking sector is dominated by four major banking institutions, namely Standard Bank, Barclays South Africa, Nedbank, and FirstRand. In order to cope with the regulatory and technological disruption, these banks were relying on the consulting industry to help with business transformation and IT architecture…. EY reveals that the banking sector had a frustrating year last year, having registered a relatively good performance in the first half of the year, but pointing back downwards by the second half. GDP growth in South Africa stood at 1.3 percent last year, which represents an increase from 0.5 percent in 2016, but a major dip from 2012 and 2013 levels of 2.5 percent and 1.8 percent respectively. Growth in headline earnings for the banking sector, however, fell by 0.9 percent from 6.6 percent in 2016 to 5.7 percent in 2017. These levels are extremely low when compared to the 2014 and 2015 levels of more than 16 percent, and represent the lowest rate of growth for the country’s banks since the Global Financial Crisis in 2009.”

The land question and national wealth

Overall since 1994 when the ANC came to power, the overwhelmingly majority African population controls only a small portion of the economy. As it relates to the Johannesburg Stock Exchange in 2017, only 3 percent of shares were owned by the indigenous people.

Skilled and professional fields are continuing to be dominated by Europeans. Even after years of initiatives such as Black Economic Empowerment, only 14 percent of top management positions are held by Africans although they make up 78 percent of the labour force. [[ii]]

Land ownership, which was a key demand within the national liberation struggle has fallen far below of what is needed and desired. White-controlled mining firms, factories and agro-business enterprises represent the bulk of land usage. At the time of the end of apartheid 80 percent of the land was in the hands of the European settlers. Since 1994 land reform has been at a snail’s pace with the most optimistic estimates of some 10 percent being transferred to people within the African majority.

The debate surrounding land reform is clearly a precipitating factor in the current economic crisis gripping South Africa. Imperialist states such as the US have expresses concern over the redistribution of commercial farms.

Republican President Donald Trump stated during August that he was directing Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to investigate the plight of white farmers as it relates to the violence directed against them and the impact on their status if the constitution is amended to nationalise the land without compensation.

South African political officials responded expeditiously by countering the tone of Trump’s comments emphasising the right of self-determination and sovereignty of the country. This does not, however, shield South Africa from possible sanctions and other forms of intervention into their internal affairs by the West operating in conjunction with the white-dominated ruling class inside the country.

The lessons of neighbouring Zimbabwe since 2000 remain vivid when the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriot Front party passed legislation legalising the expropriation of over 50 percent of farms controlled by the British settlers who had taken the land as part of the 19th century colonial process. Draconian sanctions, the creation and financial backing of pro-Western opposition groupings, along with an intensive destabilisation program through the corporate media and an aggressive diplomatic offensive could easily be enacted against the ANC government in South Africa.

Mindful of the international balance of economic power, Ramaphosa has again sought to minimise the concerns of the whites and their international supporters. In a letter published as an opinion piece in The Financial Times on 23 August, Ramaphosa said: “This is no land grab. Nor is it an assault on the private ownership of property. The proposals will not erode property rights, but will instead ensure that the rights of all South Africans, and not just those who currently own land, are strengthened.”

Despite these proclamations by the president, the African masses of workers, farmers, rural proletarians and youth cannot move forward without radical economic transformation. The ANC and its allies must rely on the African majority to maintain its political authority in the event of a worsening economic crisis engendered by the crisis in capitalist production and exchange coupled with the desire to maintain the status quo.

*Abayomi Azikiwe is Editor at Pan-African News Wire

[i] http://www.sacp.org.za/main.php?ID=6711 accessed 8 September 2018

[ii] The Conversation, 31 January 2017

- Log in to post comments

- 3339 reads