Gaddafi and African unity

Following Muammar al-Gaddafi’s election as the African Union’s new chairperson, Tajudeen Abdul-Raheem calls upon the long-time Libyan leader to promote genuine strides towards greater pan-African unity. Noting Gaddafi’s traditional support for minority groups and left-wing political causes across Africa and around the world at large, Abdul-Raheem argues that substantive achievement will rest on the ability of the new leader and the AU to effectively engage with pan-Africanists at all levels outside of the corridors of governmental power.

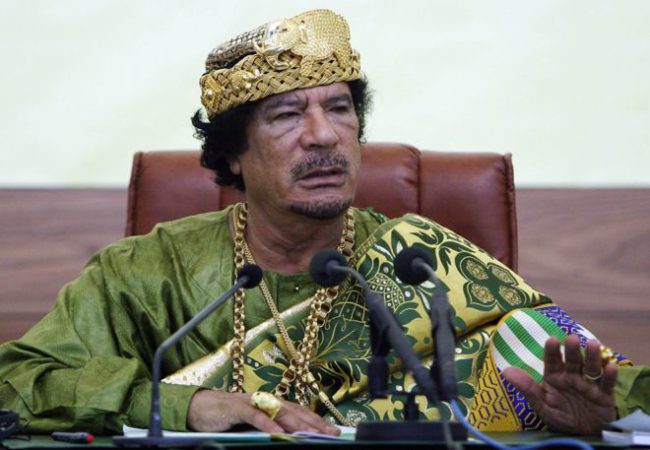

The leader and our brother Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi has just been elected chairperson of the African Union. As to be expected around anything to do with the leader (40 years in power this September) of the Libyan Arab socialist Jamahiriya, there is a controversy which will not abate for the next 12 months of his tenure as chief spokesperson for Africa’s premier diplomatic and political forum.

For those of us with longer memories we can rewind to a different time and age in 1982 when Gaddafi was prevented from becoming chairperson of the former Organization of African Unity (OAU) by an unholy alliance of internal reactionary leaders and external Cold War-driven campaigns against the then fiery revolutionary leader led by the West, with the US as the principal Force of opposition. Gaddafi was then a pariah to many Westerners and their puppets of African allies. Libya was hosting the OAU summit but many African leaders stayed away and a quorum could not be obtained. Consequently, the outgoing chairperson, one Daniel arap Moi, a ‘model’ African leader, in the eyes of London and Washington, had his term extended. Moi did not even go to Tripoli. I recall that President Shehu Shagari of Nigeria also stayed at home while hypocritically expressing the wish to join his colleagues in Tripoli if quorum was obtained. It did not occur to him that by staying put in Lagos he was preventing quorum from being formed!

The real reason was that many of these leaders distrusted Libya’s revolutionary position and Gaddafi’s support for different radical opposition activists including the forces behind military coups. Tripoli was a Mecca to all kinds of revolutionary groups that were fighting rotten leaders, often Western-backed, allegedly ‘moderate leaders’ in whose hands imperialism and neo-colonialism felt safe in Africa. While he was unpopular with many of the governments he was a hero to many ordinary people, radicals, youths and students because of his outspokenness and willingness to face down the West and support socialist and revolutionary forces both in Africa and internationally. It was not just coup leaders that Libya’s leader supported; Gaddafi was a pillar to many liberation movements across Africa including South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC), Namibia’s South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO), and the Patriotic Front in Zimbabwe, as indeed he was to Luiz Inácio ‘Lula’ da Silva in Brazil, the Sandinistas in Nicaragua and other leftist groups in South America and the Caribbean, along with civil liberty and minority groups and hard Left groups in Europe, Islamist leftist forces everywhere such as The Nation of Islam and other black nationalist and Native American groups in the US.

Despite his ideological alignment with the socialist bloc Gaddafi was neither a Moscow or China surrogate leader. In spite of supporting mainstream liberation movements in an age when such organisations claimed to be the ‘sole representative of the people’, Libya often supported different groups from the same country and even different factions of the same groups. It also had an infinite capacity to switch support from government to opposition or vice versa. Any regular participant at the various Al Mathaba events and training at that time will readily attest to the presence of a motley of groups from all over the world that were fellow travellers in Tripoli in those days, courtesy of Libyan solidarity and internationalism.

Sometimes with friends in Libya you do not need enemies. Libya’s unpredictability was both an indication of the country’s independence and Gaddafi’s attempts to create a third way between the two dominant blocs. He never quite succeeded but the relative fabulous wealth of the country and the popular legitimacy of the Al Fatah revolution enabled it to be a force to be reckoned with. It is not just Libya’s wealth but the orientation of its leadership that cemented the country’s power, because in comparison Nigeria, Algeria, Egypt, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Zaire under Mobutu, Angola, Botswana and a few other countries in Africa have tremendous wealth yet did or do not have a similar level of influence.

Imperialism fought against Libya for a long time including several coup and assassination attempts and Tripoli bombings (Ronald Reagan’s pre-emptive strike of 1986 missed Gaddafi only by a whisker). Libya also fought Euro-American hegemony by all means at its disposal. But it was Lockerbie that finally led to sanctions being imposed on Libya for 10 years. The sanctions regime nearly brought Libya to its knees. It was pan-African diplomatic and political solidarity that helped Libya to find a diplomatic end. It was Africa’s resolve and threat to break the sanctions unanimously adopted at the 1998 Ouagadougou summit that forced the hands of the UN Security Council. Mandela, Museveni and Rawlings were instrumental in instigating the change. The OAU gave the UN, the US and Britain an ultimatum to accept the trial of the Libyan suspects in the Netherlands instead of Scotland. Mandela even went on state visit to Tripoli twice in one week. Who could have imposed sanctions on Mandela for breaking sanctions against Libya?

The lessons of Lockerbie were what dictated Gaddafi’s renewed interest in African unity and his belief that African states could wield more influence if they were to act together. Africa held together whereas the Arab league, the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC) and other pan-Islamic or pan-Arab diplomatic and political forums that Libya belonged to could not back up their solidarity with any tangible action. His gratitude to Africa led to the extraordinary session of the OAU in Sirte in September 1999. In the search for a faster process of African unity, it was the Sirte Declaration that led to the transformation of the OAU to the African Union. By this time Libya had more or less abandoned the policy of changing African governments in exchange for just having friendly relations. The world had already changed too. By then many pro-Western governments in Africa had become post-Cold War ideological orphans. And many of Libya’s former rebel friends had also assumed power in a number of these countries. Even those leaders who did not share Libya’s revolutionary ideas learnt to accommodate the country. You may not be firm friends but you do not want it on your enemy’s side.

Libya’s rehabilitation in Africa with friends in all the national capitals preceded its international rehabilitation with newfound friends in London, Washington, Rome, Paris and Brussels. Post-Lockerbie Libya has concentrated its intra-African diplomacy on state-to-state relations and pan-African business enterprises that have made it a leading financial and investment player in many African countries in areas like hotels, banking, agriculture and mining. Increasingly Libya is becoming more like China in its African relations.

Libya’s power and influence across Africa is therefore not just because it uses money to bribe leaders or finance ruling parties but also as a key player in investments, buying privatised state assets and real estate, offering soft loans, and bartering trading oil for other assets.

It is not afraid throw its weight around but also is able to be willing and always ready to put its money where its mouth is. Against the caution of the bureaucrats in Addis Ababa and the lack of political will of many of the continent’s leaders, since 1999 Libya has been pushing for faster unity. Unfortunately it is concentrating too much on states instead of also building people-to-people dialogue and supporting grassroots movement in every country to nurture local constituencies for pan-Africanism. This misguided emphasis on leaders makes it easy for reluctant leaders to throw the all important issues around union government to committees, study groups and more committees since most of them do not believe it will or should happen in their lifetime.

Unlike in 1982 there is no big external interest in stopping Gaddafi from being the AU chairperson. After all, he is now great friends with those who made him a pariah before. In Africa itself the Moi or Shagari of today’s Africa no longer fear that Gaddafi will overthrow them; rather disagreements centre on the pace of African unification. They have accepted that it was better to have Gaddafi ‘pissing out from inside’ rather than ‘pissing in from outside’. They have perfected how to manage his eccentricity while giving him the illusion that he is winning. It is a war of attrition.

That reduces Gaddafi to a mere irritant. Since Libyans are not known for caring too much about details all their apparent political gains will prove to be phyrric at the committee level, buried in legalese and politico-bureaucratic fudge.

Gaddafi’s assumption of the post of chairperson of the AU will ensure that the issue of union government remains on the agenda for the year, but I doubt if much progress will be made unless Gaddafi changes his approach and learns the right lessons of the past 10 years of re-branding the OAU. It is not more noise that we need but concrete strategic actions. One, changing the name from AU to African Union Authority will not make any difference if the organisation lacks the power both politically and economically to exercise its authority. Two, Gaddafi has to give up the razzmatazz and his penchant for political form rather than content. Three, he should stop childish pranks like calling himself ‘king of kings’ and allowing himself to be a pawn in the hands of all kinds of charlatans who will give him any title as long as Libya continues to sponsor their useless gatherings. Four, African unity can only be built by committed pan-Africanists who are not just temporary residents of state houses but who operate at all levels in every country, be they political parties, the private sector, trade unions, mass organisations, civil society and non-governmental organisations, professional associations, youth representatives, students, parliamentarians, and the media. Bribing leaders may ‘win’ resolutions but yield no concrete actions leading to unity.

But above all Gaddafi needs to lead by example. Libya must politically educate its own citizens and stem anti-African xenophobia in the country and stop pursuing immigration policies and pacts that make it a gatekeeper for Europe. Gaddafi must stop promoting dictatorships by openly supporting leaders who do not respect the wishes of their people with reckless proclamations like his infamous remark that ‘revolutionaries do not retire’. After 40 years in power he needs to show that the Al Fatah revolution is able to sustain itself without him. If he does not have confidence in Libyans to rule themselves without his ‘guidance’ after all these years it will be very difficult for him to inspire discerning Africans about our collective future.

As a friend of Libya for more than two decades and someone who has met Gaddafi several times and believes that he means well for Africa and who knows that he is not as crazy as his caricatures make out, I am also anxious that the messenger is now the main obstacle to the message. He readily plays into the hands of the reactionary bureaucrats of our union, the opportunistic populism of his own personality-driven political machine in Libya and the political obscurantism of unwilling leaders who will say yes to his face while working assiduously to block him as soon as his back is turned. The business of unity is too important to be left to the whims and chagrin of leaders. It has to be anchored on sustainable institutions that are well thought-out and well costed and budgeted for. There is enough in the constitutive act of the African Union that any further reviews agreed in Addis Ababa can only advance the interests of the enemies of unity who are determined to put the brakes on any progress.

* Tajudeen Abdul-Raheem is general secretary of the Global Pan-African Movement, based in Kampala, Uganda, and is also director of Justice Africa, based in London, UK.

* Please send comments to [email protected] or comment online at http://www.pambazuka.org/