Potency of Walter Rodney’s ideas 38 years after assassination

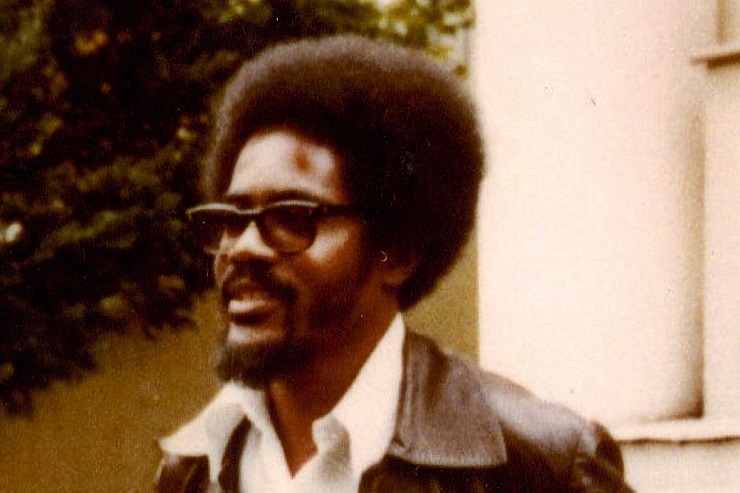

Thirty-eight years have passed since Walter Rodney was assassinated in Guyana on 13 June 1980 in Georgetown, Guyana’s capital city, but his legacy lives on beyond his home-country.

In the 2014-2016 Commission of Inquiry into the circumstances that led to his death, evidence was produced that showed that the device that exploded in his lap, and which was constructed by Guyana Defence Force army sergeant Gregory Smith, was remotely controlled from a range of frequencies normally accessed and controlled by state security agencies. [[i]]

However, despite the evidence and clarity brought by the Commission of Inquiry, the political controversies that have haunted Guyana since his assassination have not disappeared. The government of Guyana is yet to accept and use the findings and recommendations of the inquiry as a means of putting the matter of his killing to rest, bringing needed closure to his immediate family, friends and colleagues globally, and beginning the long-awaited path towards National Healing and Reconciliation. Sane observers in Guyana and around the world have looked on in dismay as the governing coalition partners chose to make what could only be construed as strategic and tactical errors as they stumbled in their dismissal of the report of the Commission of Inquiry. This approach is clearly unfathomable. Walter Rodney cannot be wished away. Yes, his physical body was killed, but he lives in his ideas, and his ideas continue to have potency and power.

National Healing and Reconciliation was the platform on which Walter Rodney stood firmly between 1973 and 1980. In that period of intense activism, he helped to forge the establishment of the Working Peoples Alliance (WPA), and a rise in activism by working people and civil society that was phenomenal, beyond anything seen before in Guyana or any other country in the Anglophone Caribbean. Rodney’s organising in Guyana gave an insight into the thesis he adumbrated in his scholarly writings, more especially in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa where he explained that the economic transfer of Africa’s resources which led to its structural underdevelopment was only possible because of the political and cultural underdevelopment of African society – in other words, through active collusion or alliances between the ruling classes in Europe (white) and the ruling classes in Africa who were local lackeys of capitalism (black). Within the construct of this alliance, the Atlantic slave trade became possible. Within the construct of this alliance, racism, the scourge that has divided humanity based on skin colour, and hierarchies in access to resources based on how close humanity is to whiteness or to blackness, became the global standard. This of course has led to the conundrum of economic inequality-based on skin colour.

Being a scholar, Walter Rodney was interested in exploring the reasons for the deepening of structural economic and political inequalities between the rich and poor counties, between the rich and poor in poor countries, and between races and ethnic groups in countries such as Guyana. He felt that independence should have halted the excesses, and hence was alarmed that the inequalities continued to widen after independence. As a gifted historian, he recognised that the problem lay in our understanding of our history, and in the structure of the management of our natural resources. From this standpoint, Walter Rodney became too hot to handle for the ruling elites in Guyana, in Jamaica, and some may argue, in some countries in Africa. He unsettled the structure of local politics. In Jamaica he grounded with the Rastafari and the working people and taught them to see their underdevelopment as a factor of the collusion between their ruling elites and the elites of global capital. This led to his banishment from Jamaica in 1968. In Guyana, he was banished from the University of Guyana, but being a Guyanese, he could not be banished from the country. The only means of banishing him from the country that was available to the ruling elites was silencing him by death. But despite his being banished by death, his views have not died. They are now more potent and relevant than ever. This is because the gap between rich and poor countries, between the ruling elites and the working peoples, and between racial/ethnic groups continues to expand.

So, 38 years after his assassination, students, activists, and lay people ask, what would Rodney be doing if he were here today? Recently, I was asked this question by a couple of people from Guyana, who are uncertain that the new-born possibilities of wealth from oil discoveries in the country would bring much needed relief to the economic plight of the clear majority of Guyanese. My short answer is, the sugar windfall between 1975 and 1990, the gold windfall (Omai, the largest gold mine in South America was situated in Guyana) after 1985, the rice windfall between 1990 and 1996 – none of these brought economic relief to the people. For a country with a population of less than 800,000 with the natural endowments we have, almost everyone should be in a happy state. So, how will oil change the economic situation of ordinary Guyanese when there is nothing much to show from all the wealth produced so far, especially since independence?

The long answer to this question lies in understanding the structure of underdevelopment, which is economic, political, and socio-cultural. In his practice and in his primary work, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Walter Rodney explained that the problem could only be addressed if the people are able to benefit from both the intrinsic and added value of natural resources. With regards to Africa, he argued that the basic structure of the underdevelopment paradox lies in the production of raw materials locally for export, while processing that adds value is done in the Western developed countries, none of which is ever returned. This helps to produce the power structure that enables further and deeper processes of exploitation of the working peoples by the global and local elites. More importantly, he pointed out that the role of local lackeys is to produce the enabling local political and economic power structure that aid the transfer of wealth through the way natural resources are mined and managed.

Therefore, Walter Rodney called for and threw his life on the line to produce a seamless connectivity between the university, the people and activism. Such activism he argued must lead the people to seek to set up democratic people’s power institutions to protect the natural resources of their country, from exploitation that leads to wealth transfer, and from theft of national patrimony that is not just about the transfer of wealth beyond national borders, but also about the transfer of wealth in undemocratic forms within the nation state. This is why, while he was a critic of imperialism (the structure of wealth transfer from poor to rich countries), he was even more critical of the local lackeys of imperialism (the structure of wealth transfer from working people to the rich within poor countries). There are those who make the argument that this was a tactical error. I don’t agree, because all politics, all production, and all processes of exploitation are local: the real struggle against imperialism is at the local level. Our experience since independence with how political parties who generally rail and identify imperialism as the main enemy – the way they manage their countries leaves a lot to be desired. Since 1990 almost all these leaders, who were formerly left leaning have functioned as the business managers of foreign capital (imperialism), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. They became local lackeys of foreign control (imperialism).

Recently I was in Accra, Ghana for the Kwame Nkrumah Intellectual and Cultural Festival, where I was shocked to see so many young people who should be in school, hawking foreign consumer goods along the highways and byways. I am told that what I experienced in Accra thrives in most of the major cities in the post-colonies. This confirms the view that political leaders of our age in the post-colonies are more interested in latching on to the banner of consumerism, the bane of Western society. Walter Rodney would have been a thorn in the side of this kind of leadership—Leadership that colludes with foreign and local capital involved in land grabs, and who stands idle as women, youth, and the poor are denied equality of access to land.

In African, Caribbean, Asia, and Latin America, equality of access to land was a necessary condition and banner in the anti-colonial independence struggles. This was one of the recurring themes at the Kwame Nkrumah Festival. For instance, in one of the panels a young woman from Burkina Faso who is denied her right to land ownership and the possibility of equality with males her age to produce her subsistence, asked “what is the answer, what can I do to get equal access to land with my husband, and what can I do to ensure that I am treated equally in the society.” These are not new questions. Such questions remind us of the unfinished struggle for equality. This is the kind of problem that prevents communities from moving forward. In my response I pointed to the example of women in Latin America who organise under the banner of La Via Campesina, as they struggle for communal land rights and food sovereignty. [[i]] Land rights and food sovereignty would have been at the forefront of Walter Rodney’s intellectual and activist agenda if he were with us today.

As an intellectual, Walter Rodney was not afraid of mingling with everyday people; indeed, he believed that producers, the workers and farmers, were really the most important elites in any country. He was a firm believer that the people must be involved in decision-making and in government; and he understood the role of the intellectual in teaching the working people to form social movements as a safeguard against collusion between local and foreign lackeys of imperialism. Hence in Guyana, where he worked tirelessly to construct the framework for a Government of National Unity and Reconstruction, he knew that for this to become a reality, the people had to be taught the reasons for the structure of exploitation. This led him to ground with workers, farmers, and sympathisers of the working people within civil society and from across the ethnic divide of Guyana.

38 years after Rodney, Guyana faces the challenge of further estrangement of its resources as Exxon Mobil embarks on exploitation of its offshore oil deposits: it is a moment that calls for education and mobilisation of its working people to force their leaders to take decisions in the interest of the populace. Guyana can learn from a place like the Democratic Republic of Congo where today, with 80 percent of the world’s Coltan, which is mined to produce essential elements required for the smart phone, the people who benefit from this resource are the local warlords and foreign capital. At a time when the natural resources of poor countries are being depleted, and the lands of the poor are being grabbed, a new breed of intellectuals must arise and challenge themselves to educate the people, so that they can renew the struggle for equality and decency, which waned after the IMF onslaught which began with the neoliberal agenda that began to be imposed in the mid-1980s.

If Rodney were with us today, he would have urged the African Union and the Caribbean Community to be true to the people of Africa and the Caribbean, and to end the pussy footing as lackeys of foreign capital. He would have urged the people to elect governments capable of striking hard bargains with global corporations such as Exxon Mobil, Apple and others – hard bargains that ensure benefits for the people, including the erection of much needed social and cultural infrastructure. [[ii]] He would have urged the working people to build lasting institutions to act as checks to ensure that no government enjoy unbridled political control and power. In Africa and Latin America, sites of massive land grabs over the last decade, he would have urged governments and the people to safeguard the gains made in Land Reforms in the period of the anti-colonial and post-colonial struggles. [[iii]] He would have been critical of governments and the African Union and would have been on the side of emerging social movements, such as La Via Campesina and other food sovereignty movements. [[iv]]

In the United Sates of America he would have been supportive of the black lives matter and me-too movements and would have urged all working peoples to form a bond to defend the rights of immigrants, people of colour, and women. In China he would have urged for respect for the rights of workers and farmers, whose rights are being trampled as a new breed of capitalist emerges. In India, he would have been supportive of the social movements that have arisen, and which struggles to preserve rights to food sovereignty. [[v]] In Guyana he would have struggled tirelessly for a national dialogue to inform policy on important national issues such as, the future of sugar, the sugar lands, the future of small farmers, the future of small miners, on safeguarding the environment from further decay, sustainable forestry, protection of the equal rights to land and access to natural resources by the indigenous peoples, the country’s relationship with the IMF, and how to relate to large global companies such as Exxon Mobil, as they set about to expropriate the oil deposits in Guyana’s rivers. [[vi]] It is a shame that 38 years after his death, the institutions he helped shape in Guyana have become mere shadows of their former selves. As we mark yet another anniversary of his assassination, I urge that we all reflect seriously and honestly on the tasks ahead.

* Doctor Wazir Mohamed is a Guyanese who was a colleague of Walter Rodney in the struggle for a multi-racial Guyana. As a member and leader of the Working Peoples Alliance, Doctor Mohamed spent 25 years of his young life and rose to the rank as Co-leader of that party before leaving to pursue graduate studies in Binghamton, New York in 2000. He is now an Associate Professor of Sociology at Indiana University East in Richmond, Indiana.

Endnotes

[iii] Saturnino M. Borras Jr., Jennifer C. Franco, Sergio Gómez, Cristóbal Kay & Max Spoor (2012) Land grabbing in Latin America and the Caribbean, The Journal of Peasant Studies, 39:3-4, 845-872, DOI: 10.1080/03066150.2012.679931

https://www.oaklandinstitute.org/scramble-african-land

Moyo, Sam. (2008). African Land Questions, Agrarian Transitions and the State: Contradictions of Neo-liberal Land Reforms. Africa Books Collective

[vi] Controversy continue to swirl around the deal struck between the government of Guyana and Exxon Mobil. Many calls for the deal to be renegotiated. Here is one such media report - https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-05-01/exxon-defends-guyana…