Remembering Nyakane Tsolo: The true history of Sharpeville must be told

Post-1994 South Africa has a theatrical crisis of selective amnesia and partisan remembering of history. History telling, whether at school, university, in the media or public celebrations and commemorative events, is biased towards a singular political trajectory and one particular school of thought that is portrayed as the sole agents of the socio-economic and political transformations that have apparently occurred in the past 24 years.

In democratic South Africa there is neither democracy nor justice when it comes to narrating critical historical events and moments. There is rather a subtle consistent perpetuation of particular memories as less or more valuable and significant than others. South African historiography after 1994 marginalises particular voices while structuring others as monolithic.

The reconstruction and rewriting of histories about the Sharpeville Massacre which occurred on 21 March 1960, and the re-constitution of that day as a historical and a depoliticised “Human Rights Day”, is but one of many examples of this unfortunate political bias and narrow approach to the telling of history.

As we commemorate the 58th anniversary of the Sharpeville Massacre, as well as the 40th anniversary of the death under banishment of Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, we should reflect on the construction and narration of public memory about historical events and public holidays in South Africa today. The government, through its various departments has already began bombarding the public with mantras of a decontextualised apolitical “Human Rights Month”.

For the past two decades the African National Congress (ANC) government has unashamedly celebrated their “Human Rights Day” with all manner of festivities, glamour and speeches without ever acknowledging or speaking to the role played by Sobukwe and other leaders of the Pan-Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC) like Nyakane Tsolo in the courageous events that led to the ruthless Sharpeville Massacre.

Yet, the Sharpeville Massacre occurred as a result of the PAC’s Positive Action Campaign against Pass Laws which followed the earlier Status Campaign championed by Robert Sobukwe shortly after the formation of the PAC in 1959. Throughout Azania leaders of the PAC heeded Sobukwe’s call and rallied the African masses for this campaign.

On 21 March 1960 the young Philip Kgosana led the PAC march in Langa Township in Cape Town; Zachius Botlhoko Molete led the PAC march in Evaton; George Ndlovu led the PAC march in Alexandra Township; Robert Sobukwe led the PAC march in Soweto; and Nyakane Tsolo led the PAC march in Sharpeville. As per Sobukwe’s instruction to “go to jail under the slogan ‘no bail, no defence, no fine’”, all these leaders, including Sobukwe, were arrested on that day.

At the time the ANC, through its Secretary General, Duma Nokwe, spoke out against Sobukwe’s call for a Positive Action Campaign against Pass Laws, dismissing it as “opportunistic”. Nokwe issued a lambasting statement in the Sunday Times of the 20th March 1960 saying, “We must avoid sensational actions which might not succeed, because we realise that it is treacherous to the liberation movement”. The ANC distanced itself from the campaign and urged its members not to participate.

Today, in their quest to silence and erase Sobukwe and the PAC from the national consciousness and collective memory of the nation, to project ANC aligned leaders as the sole actors and “super men” in the liberation struggle, the ruling party consistently celebrates “Human Rights Day” without ever mentioning the name of Nyakane Tsolo, the PAC leader who led the 1960 campaign in Sharpeville.

The PAC established a branch in Sharpeville in July 1959, three months after its formation, led by two Tsolo brothers, Nyakane and Job. Nyakane Tsolo served as the branch secretary and mobilised people on the ground; he was effectively the face of the PAC in the greater Vaal area, Sharpeville specifically.

And on Monday, 21 March 1960, Tsolo was the man in front at Sharpeville and when the racist settler police called for the black crowd to disperse, he told them “I am responsible for these people. If you want to disperse people disperse your police”. Tsolo further declared to the police “we will not call this gathering off until Sobukwe has spoken”. The rest is history.

Today, like his leader Sobukwe, Nyakane Tsolo has been rendered an insignificant figure in the annals of South African history, blotted out, silenced and erased from the public memory around the Sharpeville Massacre, an excruciatingly obscure figure – barely known, remembered or celebrated. There are no monuments built in his name, no street names, no buildings, songs or poems in his honour. No public speech reader has ever mentioned his name.

The erasure of Sobukwe, Tsolo and others from public memory and national consciousness around so-called “Human Rights Day” enables the muting and absence of explicit references to the broader histories that informed and shaped the massacre – a malicious omission calculated to also deny and erase the historical agency and contributions of other important figures in the liberation struggle. This erasure is meant to depoliticise Sharpeville and dissociate the anti-Pass campaign from the broader struggle against land dispossession.

While the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) held hearings of human rights violations in 1996 addressing a sequence of violent events, beginning with testimonies about the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre, it also sustained this omission. Nyakane Tsolo, the man who led the march and arrested for incitement on that day, was not mentioned anywhere in the TRC’s report. Nyakane Tsolo was not requested, nor did he offer testimony at the TRC; a critical narrative silenced.

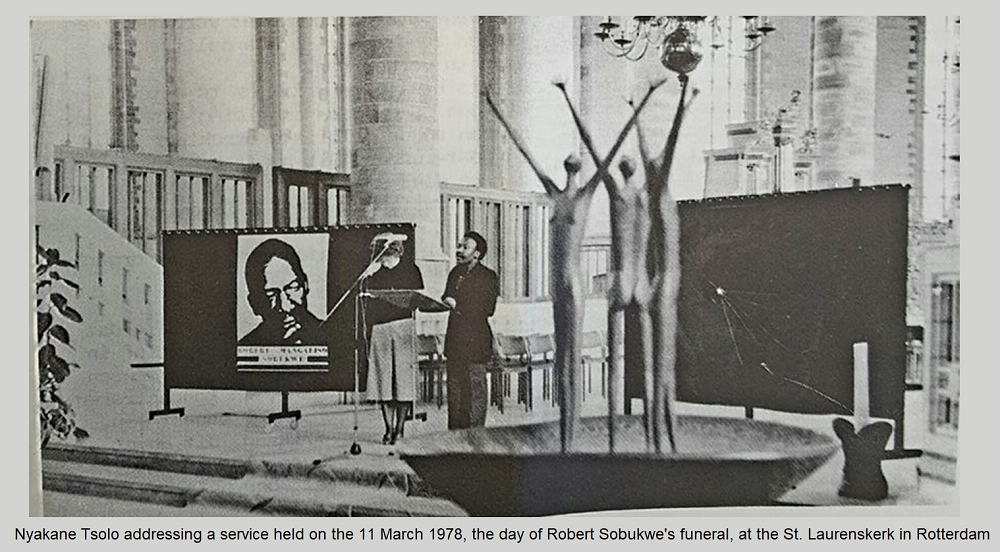

Although not remembered or acknowledged, Nyakane Tsolo suffered greatly for leading the Sharpeville protest. He was incarcerated, interrogated and tortured severely. When he got bail in 1961 he fled to Lesotho and later underwent military instruction in Egypt as a commando, training with Egyptian special forces. Between 1963 and 1973 Tsolo lived in East Germany, but in 1973 he left Germany secretly with his family and took refuge in the Netherlands. He remained in Rotterdam for the rest of his exile, designated as a PAC representative and working with local anti-apartheid bodies. Despite his inclusion on the PAC’s electoral list in 1994, Nyakane Tsolo maintained his home in Rotterdam and only returned to Azania at the end of 2001. He died of a stroke a year later.

Under the ANC government today the tragic Sharpeville Massacre has become an occasion to celebrate the advent of a perceived, yet non-existent, “human rights dispensation”. For young people “Human Rights Day” is just another boring holiday without any significance, void of any leaders worth recalling. Besides Nyakane Tsolo, all of the victims of Sharpeville are generally unknown in the public memory. They are a nameless number: 69.

The rewriting of history to suit a particular political agenda pursued by the ruling party is a tragedy of the prevalent political egotism and narrow, simplistic approach to narrative and discourse; a great loss of memory for posterity, and a spit in the face to those who sacrificed their lives in Sharpeville. Academics, the media, civil society and politicians all ought to rethink their approach to the construction and telling of history and become more inclusive. For the sake of the memory of those that died, and future generations, the true history of Sharpeville must be told.

* Thando Sipuye is an Afrikan historian and a social scientist. He works closely with the Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe Trust.

I am a Pan African Based in

Permalink

I am a Pan African Based in Lesotho and stories of Nyakane Tsolo were told by Parents and Brothers