Is South Africa at a turning point?

Does the gradual increase in the number of offensive strikes starting in 2007, the occurrence of the Marikana Massacre and the farm workers’ revolt of 2012, the five-month platinum strike and the one-month metalworkers’ strike in 2014 indicate that a new wave of offensive strikes has begun? Or is this just a short-lived revival? A key question is: has South Africa reached a turning point?

A strike is a ‘social phenomenon of enormous complexity which, in its totality, is never susceptible to complete description, let alone complete explanation’ (Gouldner 1954:65). The complexity of the meaning and implications of strikes often come to the fore when offensive strikes force the attention of the state, capitalists and civil society. They lead to a varied level of interpretation not only how events unfolded but also the impact they have made.

Strikes are a key manifestation of the class struggle over the distribution of national income and reform of the labour relations system. When offensive strikes occur they can generate an extraordinary amount of pressure on the social system which often leads to structural changes such as the reconfiguring of the industrial relations system, the economy or political system. These kinds of events are referred to as a ‘turning point’.

In the immediate post-apartheid period, the trend of increased frequency of strikes continued, with the highest number of strikes in South African history of 1 324 strikes taking place in 1998. However, between 2000 and 2009, the strike frequency averaged 71 per annum, which was even lower than the 1960s and largely defensive in character.

Despite the low frequency of strike action, the year 2007 marks the beginning of a new militancy. The 2007 strikes are largely attributed to the huge support of the offensive public service strike involving some 700,000 workers which was closely followed by the more successful wave of 26 offensive strikes mainly led by workers committees at FIFA 2010 World Cup construction sites.

While centralised bargaining and sectoral determinations continued to act as counter tendencies on strike frequency, a trend of increasing numbers of days lost due to industrial action accelerated. The 9,5 million days lost in 2007 more than doubled to 20,6 million in 2010. Most of the days lost were in the public sector, where some 1,3 million came out on another militant strike. What was significant about this strike was that the ANC for the first time felt that it could not control its major alliance partner, COSATU, which led the labour movement.

Further, there was an unprecedented increase in the share of unprotected (mainly wildcat) strikes from 44% in 2012, 52% in 2013, 48% in 2014 and 55% in 2015. Thus, the increase in the number of days lost and the percentage increase in unprotected strikes are important indicators of a change in the mood of the working class. The offensive wildcat strikes of December 2011 to April 2012 were led by workers committees of post office workers against labour broking which at the same time exposed the lack of will by unions to take up the struggle of non-standard workers. These workers ended the system of labour broking in the post office, ensured permanent employment of 5000 workers and doubled the salaries of workers to R4,000 (€258). The post office workers became the first group of workers in South African history to reverse labour broking and win a 100% increase in wages.

Both the Marikana strike and the Western Cape Farm Workers’ strike started in August 2012. Rock drillers initiated a wildcat strike at Lonmin, a platinum mine, in pursuit of a pay raise to R12, 500 (€707) per month. The strike was led by an independent strike committee and the majority union, the NUM, actively opposed the strike siding with Lonmin management. On 16th August, a peaceful assembly of workers was forcefully broken up by a special paramilitary task team killing 34 mine workers. This became known as the Marikana Massacre. This strike secured only a partial victory, with a 14% increase in wages.

The historic Western Cape Farm Workers’ strike lasted from 27 August 2012 to 22 January 2013. The strike and associated community uprising spread to 25 rural towns and was led largely by seasonal workers coordinated by locally based vanguard groups. The farm workers’ strike was historic as it was the first strike wave in the post-apartheid period to unite workers and communities, and this forced the hand of government to announce a 52% increase in the daily minimum wage. In general, employment figures in the agricultural sector indicate a trend toward stabilisation of employment along with a significant shift from casual and seasonal to permanent employment, marking the beginning to changes in the labour process brought about through the agency of farm workers against capital.

A year after the farm workers strike, on 22 January, the longest and most expensive strike in South African history broke out in the platinum industry. The 70,000 strong, five-month platinum strike hit 40% of global production. The stoppage dragged the economy into contraction in the first quarter of 2014 and cost the companies almost R24bn (€ 1,4 bn) in lost revenue. The final agreement between the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) and the three platinum producers included a R1 000 per month salary or 20% increase for lower earners.

On July 1, just over a week after the platinum strike, the 220 000 workers of the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) downed tools, demanding a salary increase of 12%. The strike, lasting one month without pay, concluded with a 4% real wage increase. While labour brokers would not be banned as Numsa had demanded, it was agreed that a number of regulatory instruments would be introduced, including the appointment of compliance officers to act on complaints of alleged abuse and noncompliance.

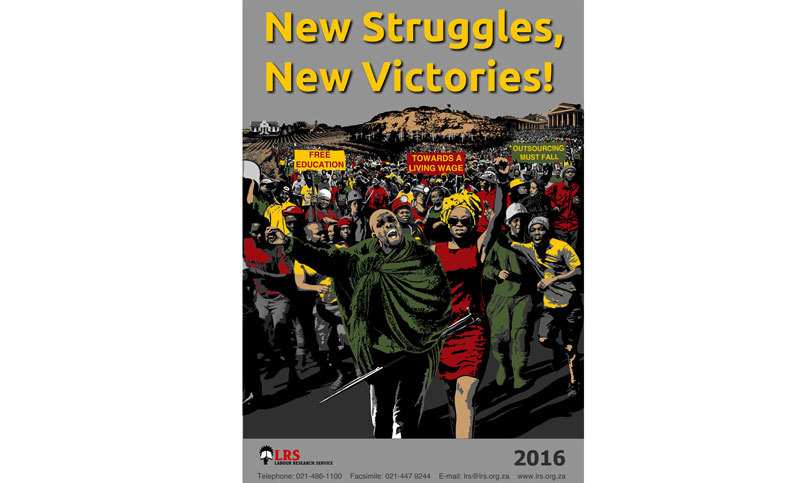

The workers’ strike wave gave impetus to the nationwide 2015 student “Fees Must Fall” protests at higher education institutions and later expanded by including the “Outsourcing Must Fall” campaign. In the absence of leadership by the National Health Education Allied Workers’ Union (NEHAWU), workers were mainly being led by workers committees which developed a call for an end to outsourcing at higher education institutions nationally. The combined actions by students-workers-academics ensured that almost all universities across South Africa agreed to end outsourcing on campuses and to employ workers on the same conditions as full-time workers, resulting in most wage increases being between 66%-163%. This event was an expression of a new level of consciousness and unity with significant implications for the power relations at tertiary institutions and constitutes the third instance of a reversal of the labour process restructuring in the current period.

However, does the gradual increase in number of offensive strikes starting in 2007, the occurrence of the Marikana Massacre and the farm workers’ revolt of 2012, the five-month platinum strike (the longest in South Africa history) and the one-month metalworkers’ strike in 2014 indicate that a new wave of offensive strikes has begun? Or is the latter just a short-lived ‘revival’ upheaval on a depressive long wave of defensive strikes? A key question is: has South Africa reached a turning point?

There are several structural dimensions that are being affected. On the economic side, we have seen direct challenges and changes to the labour process and huge costs associated with strikes to the economy. On the industrial relations level, there is pressure by business and the formal opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, for changes in the law to undermine the right to strike. Further, in January 2015, the Labour Relations Amendment Act (No.6 of 2014) took effect and ensures that vulnerable groups of employees, especially those employed through labour brokers, get adequate protection. On the political level, a new opposition to the ANC, the Economic Freedom fighters (EFF), was formed in 2013, and the more militant NUMSA was expelled from COSATU in 2015, setting the stage for the launch of an alternative, politically independent federation. Also, in the 2016 municipal elections, the support for the ANC as the manager of neo-liberalism in South Africa fell, indicating a loss of hegemony.

While some have argued that the Marikana strike wave is not a turning point, they have limited their analysis to a formalistic view of the events as a specific ‘labour dispute’ gone wrong and cite the fact that the labour relations system remains intact. Other mainstream economists instead focus on the irrationality of the actions in terms of losses of incomes to workers. Does the fact that Marikana workers lost 12% of their annual wages, that R10 billion in wages were lost in the 2014 Platinum strike, or that NUMSA workers only gained 4% in its one-month strike, relegate the strike waves as defensive incidents?

By focusing on the formalism of industrial relations and economistic views, the above perspectives fail to comprehend the complexity of strike dynamics and the historical process of class struggle that is being unleashed. As Marx said regarding the dynamic of strikes:

“In order to rightly appreciate the value of strikes and combinations, we must not allow ourselves to be blinded by the apparent insignificance of their economical results, but hold, above all things, in view their moral and political consequences” (Marx 1853).

* This article is based on extracts from, Cottle, E. Long Waves of Strikes in South Africa: 1900-2015. Forthcoming in, Balashova O, Karatepe I & Namukasa A. 2016. Where have all classes gone? Collective action and social struggles in a global context. International Center for Development and Decent Work, Kassel University, Germany.

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to [email=editor@pambazuka.org]editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org[/email] or comment online at Pambazuka News.