Remembering Lumumba: The ebb and flow of a nationalist political imaginary

As a member of the petty bourgeoisie in the final decade of colonialism, Congo’s iconic independence leader Patrice Lumumba supported the idea of a Congolese-Belgian commonwealth in which Africans and Europeans shared common interests. It was only later that he abandoned this view and aggressively championed Congolese independence in the European framework of a nation-state.

Introduction

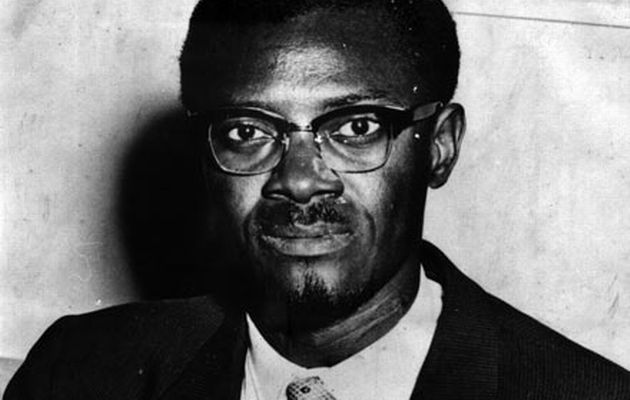

Today (17 January 2017) is a public holiday in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The country commemorates the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, its first-ever Prime Minister, celebrated as a national hero. Fifty-six years now since his disastrous demise, Lumumba’s ‘political ghost’ is far from resting! Particularly on the African continent, both north and south of the Sahara, all those who fed on the nationalist diet (whether directly as the first generation of post-independence or indirectly in the subsequent generations) are still grappling with the meaning of and quest for what could consist Lumumba’s political legacy. How then should present Africa remember Lumumba? Even more specific, what should today’s DRC make of Lumumba’s political legacy?

A scrupulous historical account of the Congo’s encounter with the West, starting with the Atlantic slave trade from late fifteenth up until mid-eighteenth century (1491-1865), through the European partitioning of Africa (1884-5) to Congolese anti-colonial nationalist struggles for independence (1955-60), testifies to the Congolese’s unrelenting quest for freedom from subjugation—political, economic, socio-cultural and psycho-spiritual. No doubt, the single most outstanding intervention of Congolese political agency in the struggle for independence and self-governance consisted of Lumumba’s nationalist political thought, which translated into practice while at the helm of the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC). The latter was a nationalist political organisation that epitomised the anti-colonial struggle against Belgian colonialism in the Congo and during Lumumba’s short-lived premiership.

The Kisangani-based Lumumba

In mid-1950s, the relatively schooled people who constituted a social cast of Congolese petty bourgeoisie, known as the évolués [1] (class of ‘Westernised’ black elites) of whom Lumumba had been a part, began to petition the Belgian colonial administration for reforms in governance. Already during his stay in the city of Kisangani, between 1944 and 1956 where he pursuit his career as bureaucrat in the colonial administration, Lumumba had distinguished himself as president, vice president, or secretary, of at least seven organisations of Congolese évolués, liaising with the governor of the province, the Belgian minister of the colonies, Auguste Buisseret, and the young king, Baudouin I, during his first visit to the Congo in 1955.

From the early 1950s, bureaucrats of the colonial state were encouraged to portray the regime no longer as a colony but as a kind of Belgio-Congolese community, in which Africans and Europeans shared common interests; a 1952 decree stipulated that Africans of the appropriate ‘state of civilisation’ should be judged as “being subject not to tribal but to civil law.”[2] In his own book, whose manuscript was completed while in his incarceration in a Kisangani jailhouse in 1956, Lumumba wrote: “My intention is not to teach our rulers, or show them the way to go—that would be presumptuous—but to enlighten them on the mysteries of the African soul: what the Congolese think of the hard facts of life, of their future and their union with the Belgians.”[3]

Throughout Lumumba’s Kisangani writings — whether as a correspondent for L’Afrique et le Monde, a Brussels weekly; in the two major Kinshasa periodicals, La Croix du Congo (a Catholic weekly) and La Voix du Congolais (a monthly bulletin) published by the state information service for the Congolese elite; or his own book, originally published under the title ‘Le Congo, Terre d’Avenir; Est-il Menacé?’ — he remained an advocate of integration, a sort of Belgio-Congelese commonwealth. Up until 1956 Lumumba directed emancipatory fights towards the advocacy for merging into a single civil service status for Europeans (Belgians) and Africans (Congolese) as a critical step in the direction of blurring the dichotomy between the colonisers and the colonised.

In a sense, Aimé Césaire’s call for departmentalisation of the French empire-republic resonated with Lumumba’s for a Belgio-Congolese commonwealth. In fact, Lumumba joined the Liberal Circle and Study Group of Kisangani—a branch of the Belgian Liberal Party— in April 1954 and in March 1956 was elected vice president of the Belgio-Congolese Union, an organisation devoted to interracial understanding and harmony. [4]

Particularly, Lumumba’s book, whose manuscript got completed in the last six months of 1956 while serving his prison sentence in a Kisangani jailhouse, was not much of a revolutionary text comparable to the writings of Mao Tse-tsung, Amilcar Cabral and Frantz Fanon, but “a political essay… for better race relations and reforms leading to greater partnership between colonial officials and the African elite in laying the foundations for Congo’s future.” [5]

The Kinshasa-based Lumumba

Congolese political historian Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja once noted that if Kisangani had given Lumumba the political apprenticeship he needed to sharpen his skills for grand political organisation and political practice, two experiences of Kinshasa—at the Ecole Postale during his training in postal service administration in 1948 and his incarceration confirmed for two years—contributed in a decisive way to the awakening of his political consciousness.[6] Following his arrest and imprisonment in July 1956 on charges of embezzlement and forgery while employed at the postal office in Kisangani, Lumumba endured prison and humiliation [7]: the first eight months of his imprisonment, from July 1957 to March 1958, spent in a jail in Kisangani, and the last six months in Kinshasa. Accordingly, Lumumba was released from the Kinshasa jail on 07 September 1958.

By 1958, Lumumba had made a total break with the colonial ideology of his Kisangani years. While establishing a nationwide political organisation on secular and non-ethnic bases had been a project of the African Consciousness group (spearheaded by Joseph Malula, Joseph Ileo and Joseph Ngalula) since 1956, Lumumba saw it all the more necessary not only to challenge the exclusionary path taken by the Alliance de Bakongo (ABAKO) party of Joseph Kasa-Vubu, but also to present a common front for wide-ranging meaningful change. Disappointed by their inability to deny Lumumba the presidency of the MNC party, the founding members the MNC (stemming from the African Consciousness group) sought to control his actions and insisted on approving the statements he would make in public. Lumumba instead outmaneuvered his conservative political contenders by establishing mass-based party sections in the various communes of Kinshasa and all over the country, beginning with the important urban and mining centres of the Katanga region of the Copperbelt and the commercial centres of Kasai and Orientale provinces.[8] By the time his detractors in the party were bold enough to try to remove him from office, Lumumba had already become unstoppable, as the MNC under his leadership obtained yet another influential consecration [9]—an invitation to a pan-African get-together in Accra, Ghana, at the peak of the decolonisation moment in most of Africa.

By the time Lumumba and his MCN colleagues too attended the Brussels Round Table Conference, the former’s political imaginary of would-be independent Congo was akin to Muhammad Iqbal’s religious nationalist stance in the context of British India of the 1930s. Particularly for Lumumba, an ideological shift from his Kisangani-years position was evident. Under what social and historical conditions, and exposed to which circumstances, did Lumumba stop ‘declaring’ and start ‘questioning’? When does an implicit disposition become an objectified role among many? When was Lumumba willing to reflect critically upon his positions, invest in other roles, forge new discursive alliances, and enrol in other trajectories?

Six weeks following the establishment of the MNC, the First All-African People’s Conference was held in Accra, hosted by Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah. The ABAKO leader Kasa-Vubu was invited to attend, but the colonial authorities refused him permission. [10] Lumumba, however, did attend—thanks to the support offered by the Pan-African Freedom Movement for East and Central Africa (PAFMECA). [11] And for the first time, he met prominent leaders of the African liberation movements, including Félix-Roland Moumié of the Union of the Populations of Cameroon (UPC), Frantz Fanon of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN), Amilcar Cabral of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), and Prince Louis Rwagasore of Burundi’s Unity for National Progress (UPRONA) party. Also in attendance were first-generation of post-independence African nationalist leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana), Gamal Abdel Nasser (Egypt), Modibo Keita (Mali), and Ahmed Sékou Touré (Guinea-Conakry).

In a myriad of ways, it was this militant stance, espoused from Garvey’s revolutionary pan-Africanism and Nkrumah’s socialist nationalism that dominated the deliberations at the All-African Pan-African Conference, which eventually bore the greatest of influence on Lumumba’s political thought post-1958. By the end of this Conference, Lumumba had made a total rupture with his Kisangani-years arguments: The objective of the Congolese people’s anti-colonial struggle, he had now conceived, was no longer racial equality in a Belgio-Congolese commonwealth, but their liberation from colonialism and the attainment of independence. Ironically, the nationalist stance that encapsulated the political imaginary of leaders of the anti-colonial struggle in most of Africa, including Lumumba’s, could not afford to wish away the very symbols of Western occupation in the independent state. Imagined by the nationalist leaders of the anti-colonial movement as a nation-state in the concert of world’s nation-states, independent Congo became somewhat ensnared in the very paraphernalia of a politically defeated colonial state, with violence and systematic exclusion undergirding its logic and at the core of its modus operandi.

Conclusion

The reconstruction of Congolese history set in motion by Lumumba since his Independence Day speech, however, did not destabilised in any significant way the economic mode of production for a different social organisation, but was instead articulated within the imaginary of yet a colonial construct—the nation-state. In his class analysis of German society, Karl Marx already depicted the coming into being of a nation-state as a bourgeois construct by the coming together of the owners of means of productions (capitalists), the intelligentsia and the ruling clergy to articulate their most respective safeties. In his treatise, The German Ideology, Marx hence posits that the very categories through which we understand social reality (values, norms, rights; brief, the sacred) are historically constructed and emanate from the ruling class, and hence constitute the expression of their best interests. [12] So, had it eclipsed Lumumba’s realisation—as the cases of Katanga and Kasai secessions would later prove—that the nation-state was indeed an articulation of the best interests of the bourgeois class.

The idea of a Belgio-Congolese commonwealth, originally contemplated by Lumumba in his Kisangani writings—was never re-imagined, let alone reconsidered. Eventually, Lumumba’s nationalist political imaginary precluded him from contemplating non-national emancipatory alternatives such as his embryonic idea of a Belgio-Congolese political future. Perhaps the greatest irony of the post-World War II decolonisation epoch (1955-60) throughout the formerly colonised world—and glaringly conspicuous in the case of Belgian Congo—is that great focus was riveted on nationalist movements and the emergent architecture of the independent state, presumed to rest on new political foundations, and yet indisposed to transcend the political imaginary of the colonial order. One critic of the European colonial order, Amilcar Cabral, for whom his objective historical conditions afforded a critical gaze at the post-war decolonisation movement, summed up his devotedness in the following terms:

“We are not interested in the preservation of any of the structures of the colonial state. It is our opinion that it is necessary to totally destroy, to break, to reduce to ash all aspects of the colonial state in order to make everything possible for our people…”[13]

Lumumba postured the future of the Congo within the logic of a nation-state, now on equal footing with Belgium, its former colonial power—perhaps Lumumba consciously viewing Kasa-Vubu as occupying the ceremonial place of Belgian King Baudouin and himself in the executive position of Belgian Prime Minister Gaston Eyskens. Yet, the Congo as nation-state had been, to cite Valentin-Yves Mudimbe, an invented construct, a product of an external imagination reconceived as a subordinated other.[14] Lumumba’s nationalist political imaginary was hence oblivious to the fact that the colonial state through its dominance of both physical space and discourse did transform colonised spaces into fundamentally coloniser’s constructs.

For certain, Lumumba’s greatest genius, in sum, was the provision of a direct link between the initial forces of resistance in both rural bases and neglected urban spaces (since the time of conquest and more especially in the last stage of the consolidation of the colonial state) and the civil societies, including the sites of évolués in various urban centres of the colonial state, which eventually drove the colonial state to cover. Lumumba’s single most significant lacuna was his uncritical embrace of a nationalist idea whose political agency both in the anticolonial struggle and the post-independent nation-state had not entirely escaped from the trappings of the colonial political imaginary. How different could the Congo’s political history from today’s vantage point ensue had Lumumba’s Belgio-Congolese commonwealth political imaginary taken hold? For this non-nationalist alternative formulation to have been abandoned without any trial, its potential (whether in terms of success or failure) has only been rendered a matter of sheer speculation.

* David-Ngendo Tshimba is a PhD Fellow at Makerere Institute of Social Research – Makerere University. He can be contacted at: [email protected]

End notes

[1] The term ‘évolué’ is used to describe those Congolese who “evolved” through formal education from a purely ‘tribal’ way of living to ‘modern’ living à la Belgian upper class society.

[2] D. Renton, D. Seddon & L. Zeilig (2007). The Congo: Plunder and Resistance. London: Zed Books, p. 71

[3] Lumumba (1962). Congo, My Country [trans. Graham Heath]. London: Pall Mall Press, p. 7; italics are mine for emphasis.

[4] G. Nzongola-Ntalaja (2014). Patrice Lumumba. Athens. Ohio University Press.

[5] Ibid., p. 57

[6] G. Nzongola-Ntalaja “L’héritage de Patrice Lumumba” In CETIM (2013) Patrice Lumumba: Receuil de texts introduits par Georges Nzogola-Ntalaja. Geneva: CETIM.

[7] Nzongola-Ntalaja (2014). Op. cit.

[8] Ibid.

[9] J-C. Willame (1990). Patrice Lumumba: La crise congolaise revisitée. Paris: Karthala.

[10] Renton, Seddon & Zeilig (2007). Op. cit.

[11] Nzongola-Ntalaja (2014). Op. cit.

[12] K. Marx [1968] A critique of The German Ideology. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

[13] Cited in C. Young (1994) The African Colonial State in Comparative Perspective. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 2

[14] V. Y. Mudimbe (1988). The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy and the Order of Knowledge. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to [email=[email protected]]editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org[/email] or comment online at Pambazuka News.