Biafrans and Onumah’s ‘prophecies’

This book is a useful contribution that will enlighten those people who want to understand why Nigeria is not working and what needs to be done. Persons in positions of leadership in the country may find it a useful guide in tackling some of the problems troubling the nation.

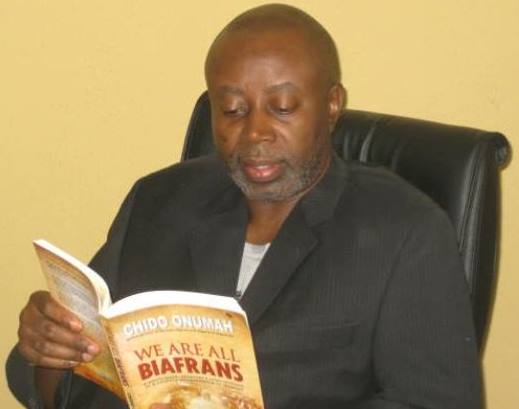

Title: We Are All Biafrans

Author: Chido Onumah

Publisher: Origami

Year: 2016

Pages: 214

Along the line of my quest for knowledge, I have always come across this cliché that Nigeria is a land of milk and honey: Arable land, mineral resources, and a large and enterprising population; variables that make a nation great. Regrettably and in spite of all of these, we have been in a pitiable situation. Whenever I ruminate over these conundrums, a whole lot of rhetorical questions keep agitating my mind.

Setting my eyes on this book, its title, We Are All Biafrans, only heightened a sense of curiosity in me towards finding out why we are described by one of the age-long canker worms we have been battling to do away with as a country. However, from the outset, as someone who has always shared patriotic feeling with each and every individual that believes in the Nigeria project, I did not see this book as only a work of art, which must be appreciated by its enthusiasts.

Rather, I saw it as a national question that must be answered, and by way of a review. I set out with a clearly spelt mission of finding out why we (Nigerians that abhor the word Biafra) would be described as such.

My curiosity was, however, appeased by the first sentence in the prologue of the book, which reads: “The young Nigerians now threatening to actualize Biafra should forget or shelve the plan. They should, through research and study, reconstruct the Biafra story…and answer the unanswered questions and supply the missing links in the story.”

With this, the author has offered these disgruntled youth agitating for a sovereign state of their own an olive branch.

Going further through the book, it appears however that the agitation Onumah describes has more to it than meets the eyes, because he metaphorically describes all of us as Biafrans, as long as we are seeking to confront the crisis which is a product of the feeling of alienation and marginalisation due to our deeply flawed federalism. He believes that such feeling is arguably widespread from the south to the northern parts of the country.

Hence, the basis for the author’s prophesies that Nigeria is sitting on a time bomb that could go up anytime. He argues that Nigeria as a country has paid dearly for allowing politics to trump patriotism and wasted much time and resources doing nothing and going nowhere.

Now, before undertaking an analysis of the book, it is important to know that this great book is a compendium of the author’s published articles in both traditional and online news outlets within the last three years (2013 to 2016), grouped into chapters one to five.

Chapter one, ‘The politics of 2015’, deals with the high-wire politics of the 2015 elections and its crucial stake in the survival of Nigeria as a country. The author, through the star article of this chapter titled, ‘2015: Why Buhari Matters’, issued a warning that, “the impoverished millions of our country men and women, the wanton abuse of rights, the unmitigated corruption, alienation, internal colonization and exacerbation of the fault lines of the country were not issues that the current political order could tackle.”

The second chapter, ‘Dancing on the Brink’, focuses on the issue of a Sovereign National Conference (SNC). In this, the author thunders that Nigeria is a big scam, a collapsed edifice that is in need of an urgent overhaul through a recognized form of representation that would carry everybody along. He says: “More than fifty years after independence, we have managed to alienate one another so much so that people still see themselves as northerners, southerners, and everything in between.”

However, the author jubilates over a glimmer of hope that resurfaced through the convention of a National Conference. In the next chapter, ‘Unmaking Nigeria’, his jubilation is cut short as he argues that “many, if not all, of the problems that assail us as a nation are rooted in the structure of the country which has been left unattended to”. He argues:

“My take is that majority of Nigerians do not really give a damn about the disintegration debate because to them the country started disintegrating the very moment it became a sovereign nation, when rulers had the opportunity to build a united and prosperous nation but they were so mired in their clannish and thieving ways to worry about that.” (Pp.65)

Reinforcing the above statement, the fourth chapter, ‘Of scoundrels and statesmen’, focuses on some individuals and groups in and out of government whose actions have either enriched our polity or reinforced it as the giant of Africa only in name. In the chapter, the author clearly spells out how most of our leaders have always failed to walk their talk and how this inability has torpedoed our growth and unity.

In Chapter five, ‘Last Missionary’, the author reminds us that we are living in a deeply fractured nation and we could only ignore that reality at our own peril. He adds that unless we sit at a table to negotiate the terms of our co-existence as a people, our country would continue to ‘go round and round’.

“There are millions of our compatriots across Nigeria for whom this country provides no succor, there are millions who feel they have no stake in Nigeria, millions who feel they been left out of the gains that independence ought to bring.” (pp.164.)

However, according to the author, all hope is not lost because we could still retrace our steps. He notes: “What the current situation calls for is a bold attempt to confront Nigeria’s seemingly intractable problem: The structure of our federalism.”

As much I appreciate Onumah's intellectual contributions towards actualising the Nigeria Project, I think this project is bigger than him and all that have written about it. That notwithstanding, this work of art would go a long way in evoking a positive thinking in the readers and Nigerians as a whole. Essentially, the book is intended to sustain the reader's interest, remain true to the empirical evidence and deliver a message, all at the same time. It is a wonderful keepsake for all those who want to understand why Nigeria is not working and what needs to be done.

In addition, this book is written in a simple, straightforward language to enable the understanding of anyone with a smattering of the English language. The font size and typeface too are reader-friendly.

One thing readers of the book may find as its shortcoming, however, is the fact that some of the articles are not presented in a chronological order which makes it difficult for the reader to come to terms with the chain and sequentiality of the unfolding of events. Such shortcomings slightly impede one’s understanding of the sequence of events presented in this epistolary tome.

It is hoped that future editions of the book will correct these and a few typographical errors noticed. All in all, readers will find it very informative and those saddled with the responsibility of leadership in the country may find in it a useful guide in tackling some of the problems troubling the nation.

* Ibrahim Ramalan is an Abuja-based writer and journalist. He can be reach at [email protected]

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to [email=[email protected]]editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org[/email] or comment online at Pambazuka News.