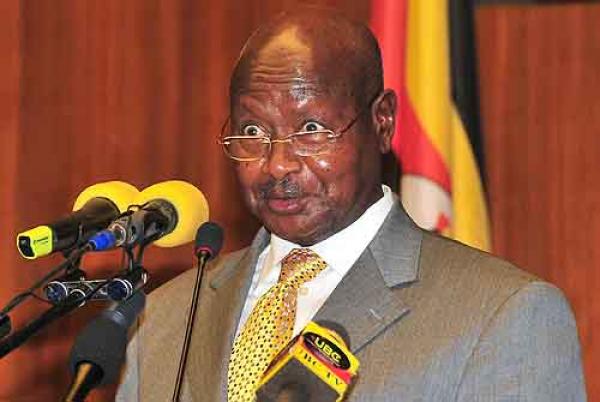

Yoweri Museveni and the future of Uganda: Beyond 30 years of militarism

For 30 years, the Ugandan leader who is poised to extend his rule in next week’s elections has presided over a militarized regime supported by the West. The citizens desperately need change but they have no way of achieving it through compromised procedural democracy. The forces for change in Uganda must re-strategize and keep up this struggle after the elections.

Ugandans go to vote in presidential and parliamentary elections on February 18, 2016. This will be the sixth presidential election since Yoweri Museveni and the National Resistance Movement (NRM) acceded to power on January 29, 1986. After 2005, the NRM-controlled parliament initiated a change of the 1995 Constitution so that Museveni could run beyond the two terms that were mandated. Millions of dollars were showered on Members of Parliament to support this change of the Constitution, but in 2016 there is considerable evidence from the MPs that they want a reinstatement of term limits for presidents.

There are seven presidential candidates in the forthcoming elections, but of these, the three most important are the candidate for the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), Kizza Besigye, the former Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi of the Go Forward Movement and the incumbent, Yoweri Museveni. Under the current law the winning candidate must win 50 per cent of the vote plus one in order to avoid a runoff.

These top three candidates had been combatants of the National Resistance Movement (NRM), the military/political front that waged an armed struggle in Uganda 1980-1986. The other two principal political parties of Uganda, the Uganda People’s Congress (UPC) and the Democratic Party (DP), decided not to field presidential candidates and are supporting Go Forward and the FDC.

In this election campaign, the three top candidates are contesting on who best can manage the economy. None of them even bothers to speak in the name of the most exploited people, and all three claim to be ‘good leaders’ who will provide ‘good governance.’

From the press reports about the support for the opposition candidates, the ruling NRM has been sufficiently concerned that it has unleashed military and paramilitary forces against opposition members. The so-called ‘crime preventers, a pro-Museveni national youth wing, have been so brutal that their activities have been condemned by international human rights organizations.

The opposition forces have garnered large numbers of youthful followers yearning for change in Uganda but this opposition has not elaborated on, or delivered, a credible project for the restructuring of the Ugandan economy. The NRM has benefitted from the divisions among the opposition and the reality that this opposition has been vague in addressing the key issues of exploitation and the impoverishment of the majority of nearly 40 million citizens. Learned members of the Ugandan society have predicted that the state will use violence to maintain Yoweri Museveni in power. The major question that comes from this period is from where will there be a new force to chart a program for real political and economic change in Uganda?

CAMPAIGN 2016

From the news reports on the 2016 election campaign, Besigye has been addressing very large rallies in all parts of the country. Citizens have flocked to his rallies with gifts and the symbolism of youths bringing jackfruit, chicken, goats and food as donations to political rallies signaled that the poor want to make up for the financial deficiencies of the opposition, FDC. The massive rallies of Besigye and the enthusiasm of the electorate has been a signal of the deep desire for change in the political direction of Uganda.

Besigye unsuccessfully competed against Museveni in 2001, 2006, and 2011. General David Sejusa, former Director of Intelligence for the NRM regime, has stated in public that Besigye won the 2006 elections and that the NRM party rigged the elections to retain Museveni. Speaking while in exile in the United Kingdom in 2013, Sejusa argued that the polls, in which Museveni was elected to a third term, were characterized by ‘widespread irregularities such as ballot stuffing, intimidation of FDC supporters, manipulation of the voters register, among others.’

David Sejusa is only one of the many Generals who had fought in the war of liberation with Museveni but who have now fallen out over the perceived plan that Museveni and his family has been grooming his son, Brig Muhoozi Keinerugaba, to become the next leader of Uganda. Those Generals who have opposed the Muhoozi Project have found themselves sidelined and others such as Sejusa who has been most outspoken, arrested. In early February, General Sejusa was arrested and remanded in the infamous Makindye prison over his proclamations about the current electoral process. The incarceration of the former head of intelligence is but one indication of the desperation of the political leader of Uganda who has brought the politics of retrogression to a new level. Sujusa remains in prison.

Thus far, other military officers in the top hierarchy of the NRM such as General Aronda Nyakairima, Maj-Gen James Kazini, Colonel Jet Mwebaze and Colonel Noble Mayombo have departed this life in circumstances which demand deeper investigation.

Neither the opposition, nor the current government has sought to fight the election campaign on the core issues that affect the Ugandan people; but have instead focused on the nebulous formulation of demanding ‘good governance.’ Neither Mbabazi nor Besigye have been open in critiquing the IMF and the implementation of the structural adjustment programs of the IMF.

THE ISSUES: PRIVATISATION AND SUPER EXPLOITATION

Anyone driving on Entebbe Road from Entebbe to Kampala will see the growing divide between the social classes in Uganda. Since 1987 when Uganda embarked on the Structural Adjustment Programs (SAP), the conditions of the working people have deteriorated considerably while the small exploiter class has grown wealthy and more conspicuous in their consumption. This ostentation of the ruling elements in Uganda has overshadowed the depth of the impoverishment of the working poor. After 1987 Uganda was a veritable laboratory of the project of neoliberalism with the NRM government aggressively implementing the principal prescriptions of cutting social services and implementing user fees. Other imperial forces had propped up the political leadership of Uganda, heaping praise on Museveni as a ‘pragmatic’ leader while Uganda gained notoriety as one of the societies in Africa heavily dependent of ‘donor’ support for their recurring budget.

Since 1987 the Ugandan government embarked on reductions in government spending; monetary tightening (high interest rates and/or reduced access to credit); elimination of government subsidies for food and other items of popular consumption; privatization of enterprises previously owned or operated by the government and massive cuts in support for public hospitals and clinics. These measures have enriched a few in the same way that they have considerably increased the burdens on the working poor.

From 1965 the Ugandan workers, poor farmers and traders lost autonomy over their organizations and the impact of commandism and militarism have intensified the impoverishment of the people. From this impoverishment one can identify ten main issues in Ugandan society:

1. The very low wages of those workers who have lost their rights to collective bargaining.

2. The impact of privatization of the economy and the retrenchment of over half a million workers adding to the ranks of the unemployed.

3. Liberalization of the cash crop sector and lower returns to the poor peasantry.

4. Increased unemployment of school leavers, along with high levels of under-employment.

5. The disarray of the provision of social services, especially in the areas of health delivery and the appalling state of public hospitals and clinics.

6. Declining standards and conditions of education – massive dropout rates and the lack of resources for the creation of jobs.

7. Political thuggery by the ruling elements.

8. Uncertainty about future of the management of the recently discovered petroleum resources.

9. The deployment of paramilitary forces, especially the so-called crime preventers, to intimidate citizens and

10. The future of the Museveni family in the future political processes.

There are numerous other issues confronting the Ugandans in this election, but this author has decided to highlight these ten points. Other East African news outlets have identified issues in the elections but these sources have studiously avoided questions of the health and safety of the working poor of Uganda.

LIMITATIONS OF PROCEDURAL DEMOCRACY IN UGANDA

Many of the reports of the technical details of the deficiencies of the machinery to supervise elections have pointed to the overwhelming control of the electoral commission by the ruling NRM. Museveni has mastered the art of guaranteeing the elections as a formality since 2001 and rigged elections in Uganda has been a textbook example of procedural democracy. This is the form of democracy where the ruling elements merely go through the motions of organizing elections with structures and institutions but in reality do everything to undermine the true expression of the free will of the people. Western ‘democratic’ agencies have been willing supporters of this form of duplicity in Uganda because Museveni has been a core partner in the global ‘war on terror.’

Not only was Uganda a veritable laboratory for the western imperial forces, but President Museveni and the NRM decided very early to subcontract the Ugandan army in the service of the most conservative sections of global capital. Hence, while the IMF was implementing its onerous medicine on the Ugandan peoples, the imperial forces were lavishing praises on the stability of Uganda and the role of Uganda as a peacekeeper in Somalia. The US military undertook the support and training of the Ugandan military forces subcontracted to the Pentagon while Ugandan private military contractors willingly sent young Ugandans to serve for the United States in Iraq. In this mix of militarism and procedural democracy, the western forces deployed hundreds of international non-governmental organizations to Uganda. Rural hospitals were parceled out to competing religious formations from North America and Western Europe.

Evidence of the work of some of these organizations came to the fore in 2012 when an organization calling itself ‘Invisible Children’ launched an exercise in mind control called Kony 2012. This so called NGO carried out an ‘experiment’ on how to mobilize the youth internationally to support the US military and their work in Uganda. The pretext of the Uganda government was that this effort by the Pentagon and the NGO was part of a wider plan to capture Joseph Kony of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), but by the time Invisible Children had rolled out their plan, Kony had been ensconced in the Central African Republic for many years.

Alongside the international NGOs in Uganda were tens of the most conservative elements of the Christian fundamentalist forces in the United States. These fundamentalists were sufficiently influential to support those elements in Uganda who offered legislation to kill same-gender loving persons. The tabling of a stringent anti-homosexuality legislation and its subsequent passage brought the conservatism of the Ugandan leadership into full international glare. The same Museveni government that championed this anti-homosexuality push later expended over $200,000 seeking to bolster his image after the negative responses to the atrocious human rights positions. http://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/Uganda-US-PR-clean-anti-gay-bill/-/688334/2665112/-/egpjctz/-/index.html

UGANDANS NOT SWAYED

If Museveni had calculated that his opportunism over the rights of same gender loving persons would endear him to the oppressed Ugandans, he was mistaken and the election campaign since 2015 has brought out the extent of the isolation of the Museveni government regionally and internationally. Uganda has very high unemployment among the youth who comprise the majority of the population. Inside East Africa, for nearly twenty years after 1986, Museveni had been a close ally of the political system of Tanzania, but after he decided that he was the kingmaker in the region, the Uganda government became isolated from Tanzania. Museveni was isolated at home and abroad and was supported by the elements of the ruling party in Kenya and sections of the Rwanda leadership around President Paul Kagame. And even in this splendid isolation, it devolved to the indicted Vice President of Kenya, William Ruto, to be one of the very few regional leaders to travel to Uganda to campaign for Museveni. Museveni became a reference point for those leaders in Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo who have embarked on efforts to extend their term limits so that they can remain in office.

MUSEVENI AS THE MAIN ELECTION ISSUE

The question that has been posed inside and outside of Uganda is, if Museveni did not achieve real change in the direction of Uganda after 30 years, why should Ugandans believe that another five years in power would lead to a dramatic change in the direction of the society? This argument has found favor with millions of Ugandans who have braved the intimidation of paid state thugs to turn out in opposition rallies. Museveni and his militaristic style has emerged as the number one issue for Ugandans in the February 2016 elections. From the images presented in the media of the turnout for the Besigye campaign in Mbarara, the heartland of President Museveni, there is a certain momentum that has developed in the country, with the masses coming out in large numbers to the rallies of the FDC. Besigye is being hailed as redeemer with poor peasants bringing donkeys for him to ride on into towns and villages.

When the campaign began in 2015 and former Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi announced his intention to run for president, insiders in the political game expected him to mount a credible campaign, but as one of the chief lieutenants of the NRM from 1986 until 2015, his campaign has not caught on inside Uganda. This lackluster campaign of Mbabazi has ensured that the popular energies have flowed to the FDC and Besigye.

Yet the FDC campaign has not zeroed in on the core issues of how to restructure the economy but has instead presented itself as better managers of the future wealth of Uganda. The FDC has drawn attention to the atrocious conditions of hospitals and clinics, to the point where the NRM government sought to ban the FDC from going anywhere near health facilities. While the FDC has pointed to the wretchedness of the poor, the campaign has not made the link between the structural adjustment programs and the conditions of Ugandans. In many ways, this opposition will remain constrained by its exposure to the international ‘donor community’ and the embrace of the International Republican Institute (IRI). The over-size influence of western NGOs and embassies is evident in the operations of all of the top candidates. It was significant that General Sejusa did not flee to Tanzania or Mozambique when he fell out with Museveni, but to Britain.

The unpopularity of Museveni has brought out hundreds of thousands of youths behind the convoys of the FDC while the NRM government has been spending millions of dollars to compromise the same youth. Violence and intimidation against the opposition has been unleashed by the recently mobilized para-military force called the crime preventers. These youths are supposed to be a volunteer force of civilians recruited and managed by police to report on and prevent crime in cooperation with the security agencies and communities. The crime preventers work under the stewardship of the Inspector General of Police, General Kale Kayihura, who has gained notoriety as a state thug in Ugandan society. In practice, crime preventers are strongly affiliated with the ruling party. Its members have acted in ways that abet the anti-social activities of thugs supporting the NRM and carried out brutal assaults and extortion with no accountability. It is this threat of violence against unarmed civilians that has unnerved sections of the intelligentsia.

Museveni himself has said that under no condition would he hand over power to the opposition. Such utterances have led to pessimism among some intellectuals with Prof Oloka-Onyango of the Makerere University predicting that there would be chaos if the opposition won the elections. He was reported to have said that,

“I do not believe that any Opposition candidate in Uganda today can win this election, which is highly in favour of the incumbenct… [If that happens], then you will have chaos or a military coup.”

LONG-TERM STRUGGLES BEYOND ELECTIONS

Evidence from all parts of Africa points to the need for numerous forms of political struggles to empower the most oppressed sections of the people. Evidence from the Egyptian uprisings in 2011 exposed the need for clarity and organizational depth to oppose presidents who want to impose their sons on society. More recently, the peoples of Burkina Faso showed the way by mobilizing in popular worker struggles to remove Blaise Compaoré who wanted to extend himself in power. Civic rebellion along with electoral struggles had taught the people of Burkina Faso not to depend on one mode of struggle.

Ugandan workers and poor farmers are demanding change, but so far the traditional opposition parties have failed to present a project that could find support among the most oppressed. Kizza Besigye has persevered over the past fifteen years, but his horizons are limited to his understanding of the future dependence on western forces.

Uganda is a very rich country with well-watered lands and massive biologic resources. The discovery of large amounts of fossil fuel, estimated at 6.5 billion oil barrels, has made this election tremendously significant for the future of the society. Secrecy surrounds the agreements about production and the future plans of an oil refinery in Uganda have proceeded without the establishment of the technical infrastructure for petroleum products to have a multiplier effect in the economy. Yoweri Museveni has promised to go back to guerilla warfare if he is not in control of these massive resources. It was reported in December 2015 that while speaking at Namutumba District, he said,

“Then you hear people say 'Museveni should go'. But go and leave oil money? They want me to go so they can come and spoil the oil money. These people want me to go back to the bush."

It is time for Ugandans to call his bluff.

Progressive Pan-africanists must oppose the thuggery of the NRM in this electoral contest.

* Horace Campbell is Professor of African American Studies and Political Science, Syracuse University. Campbell is also the Special Invited Professor of International Relations at Tsinghua University, Beijing. He is the author of Global NATO and the Catastrophic Failure in Libya: Lessons for Africa in the Forging of African Unity, Monthly Review Press, New York 2013

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org or comment online at Pambazuka News.