Inconsistencies in affirming Sobukwe’s legacy: a response to Benzi Ka-Soko

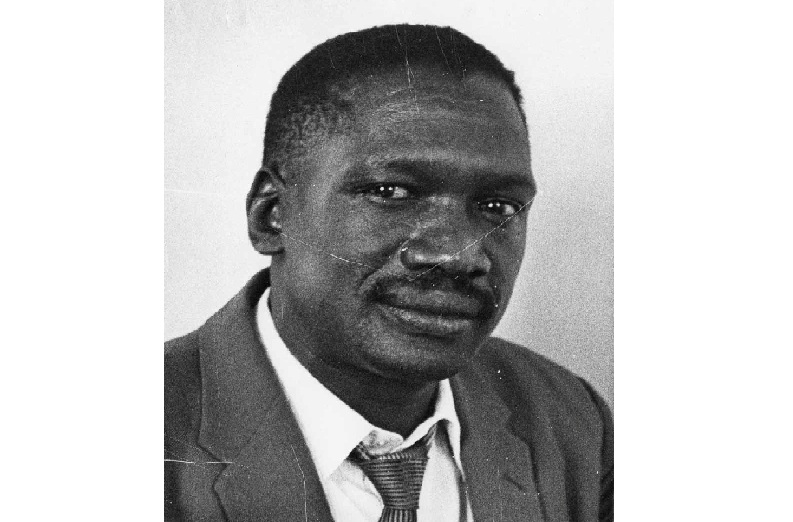

The timely City Press article by Benzi Ka-Soko on Sunday, 15 July 2018, titled “Affirming Sobukwe’s Legacy Is Imperative”, is an excellent and timely intervention in acknowledging Sobukwe’s towering, yet concealed and obscured, role in the Azanian (South Africa) liberation struggle, both as a political ideologue, an intellectual and a philosopher par excellence.

Ka-Soko’s contribution must be highly commended, particularly as Sobukwe’s name, memory and legacy continue to be side-lined and silenced in mainstream political fraternities, public discourse, media narratives and academia, even in this significant year commemorating the 40th anniversary of his orchestrated and systematic assassination under banishment in 1978.

Ka-Soko has well captured the intentions of the racist apartheid regime in attempting to silence, isolate and kill Sobukwe using the might of state machinery, the law, medical institutions and consecutive annual parliamentary processes.

But Ka-Soko also makes a few unsettling points, particularly in relation to Sobukwe’s last days when his health deteriorated, as well as subsequent literature around his legacy.

In furthering Ka-Soko’s call for the affirmation of Sobukwe’s indelible legacy, let us speak to the serious errors and misconception perpetuated in his article, only for the purpose of setting the record straight and shedding more light on the calibre of the man, Sobukwe.

It is gravely erroneous to assert that white rulers, and the entire political system of white supremacy with its organised machinery for that matter, ever drove Sobukwe “mad”.

Ka-Soko asserts that as a result of the ruthless indefinite incarceration and the solitary confinement imposed upon him by the racist parliament through the legislation and institution of the Sobukwe Clause, “Sobukwe’s psyche was severely damaged, resulting in extreme hallucinations, loss of memory, loss of language and delusions”.

Whilst the draconian Sobukwe Clause and solitary confinement were meant to destroy, break down and obliterate Sobukwe – to kill his mind, soul and spirit – Kruger, Voster and Pelser, all ministers of (in) justice, failed to kill Sobukwe.

They failed to break the spirit of the wonderful “Son of Man”, let alone reduce him to “hallucinations, loss of memory, loss of language and delusions” as alleged.

Solitary confinement, food poisoning, systematic mental torture, banishment, denial of access to medical facilities and white terrorism collectively conspired to try annihilating, not only Sobukwe’s body politic, but his entire ideas of Afrikanism, Afrikan Nationalism and Afrikan liberation.

The failed dismally.

In fact, a letter dated 4 June 1969 from the office of Justice Minister Petrus Cornelius Pelser, in response to Sobukwe’s enquiry regarding results of state psychiatrists who had examined him on Robben Island, refutes the idea that apartheid ever succeeded in breaking down the spirit and mind Sobukwe.

The letter reads: “with reference to your statement that the report of the psychiatrists was not made available to you the Minister has directed me to advise you that they merely confirmed that you state in your letter to be the case, namely that you are not a psychotic case. They also found that your personality is intact; your volition is intact; your emotional responses are appropriate; and your behaviour does not reflect a break with reality”.

The clandestine, overt and covert operations and machinations of white supremacy to wipe out Sobukwe from national memory and to systematically eliminate him from political activity failed.

Although they tried, Sobukwe’s psyche was never damaged, he never suffered from hallucinations never lost his memory, language and had no delusions.

Yes, as a result of not being allowed to speak to anyone and having very minimal human contact during his incarceration on Robben Island, Sobukwe’s speech was affected. But not to the extent that Ka-Soko depicts.

Whilst making a genuine call to the Black intelligentsia with regards to their continued refusal to effect scholarship on the ideas, philosophy and political thought of Sobukwe, it is important to note the existence of a small pocket of the Black intelligentsia that has written and published exceptional works on Sobukwe.

There are a few brave voices, equally marginalised, that refuse to remain silent about the unmatched contributions of Sobukwe in the political imagination of what could have been a liberated nation.

Therefore the answer to the question “why have the Black intelligentsia not written books on Sobukwe as one of the great leaders of the liberation movement in South Africa?” lies in the places Ka-Soko’s eyes – and those of many other political analysts and intellectuals – refuse to see: in the dark and neglected alleys of the Black intelligentsia where intellectuals like Motsoko Pheko, Elias Ntloedibe and Zamikhaya Gxabe have produced written works on the life and political contributions of Sobukwe.

Ka-Soko’s genuine appeal to the Black intelligentsia makes the erroneous assumption that the Black intelligentsia has not researched, written or published any literature on Sobukwe. But in 1985, Pan-Afrikanist intellectual and political activist, Motsoko Pheko, published the first biography on Sobukwe titled The Land Is Ours: The Political Biography of Mangaliso Sobukwe (not to be confused with the recently published book with similar title by Advocate Tembeka Ngcukaitobi). And in 1995, Robben Islander and the Pan-African Congress (PAC) stalwart, Elias Ntloedibe, published the second biography on Sobukwe titled Here Is A Tree: The Political Biography of Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe.

Both these books were be re-launched on Tuesday, 31July 2018(Afrikan Heroes Day), by the Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe Trust, in partnership with the African Flavour Books and the Blackhouse Kollective, as part of the “Sobukwe 40 Years On: A Silenced Voice of Liberation” commemorative programme.

Significantly the re-launch of these two books took place on 31 July, a day Sobukwe named “Afrikan Heroes Day” in commemoration of the death of his political and ideological brother, Anton Lembede.

But besides the books by Pheko and Ntloedibe, another Africanist intellectual, Zamikhaya Gxabe, also wrote an intimate biography on Sobukwe titled Serve, Suffer, Sacrifice: The Story of Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe.

These rare literary materials collectively constitute some of the most critical and organic literary materials, with in-depth analysis, on Sobukwe and his politico-philosophical ideas.

Moreover, the secretary for political and Pan-African Affairs in the PAC, Jakie Seroke is currently working on a coffee-table book project on Sobukwe titled Sobukwe: A Pictorial Biography; and former PAC firebrand, Thamie ka Plaatjie is also finalising his biography on Sobukwe titled Sobukwe: On A Class of His Own.

So it is untrue that the Afrikan intelligentsia has written nothing on or has neglected Sobukwe altogether, although much more can, indeed, be done.

The critical question is why political analysts like Ka Soko and many others, the black intelligentsia at large, educational institutions, politicians and media practitioners know very little or nothing about these books by Pheko, Ntloedibe and Gxabe; why are these books –written from various perspectives of insiders, colleagues, comrades, friends and disciples of Sobukwe – under circulated and marginalised from mainstream book stores, public libraries and the academia?

These Sobukwe books are largely unknown, under circulated or out of print primarily because the South African publishing and book shop industry is controlled by white settlers, working in cohort with an African National Congress (ANC) bourgeoisie, which unrelentingly seeks to bury Sobukwe’s memory and contributions.

Finally, at the end of his article Ka-Soko also makes another serious error in claiming that the aims of the Black Consciousness Movement (AZAPO—Azanian People’s Organisation), the ANC and PAC “collectively defeated apartheid using different strategies” and that “each of these organisations used different methods but they all had identical aims”.

The system of apartheid, the political incarnation of white supremacy in Azania, was never wholly defeated; nor has racism white supremacy died. Apartheid’s cosmetic outer trappings and its explicit expressions and institutions were reconstituted, reconfigured and re-formed for the “new” dispensation: settler neo-colonialism. The reform and reconstitution of apartheid was negotiated in 1994.

In fact, besides the obvious continuity of Black suffering evident daily, a white liberal journalist, John Pilger, published a book and released a documentary film titled, Apartheid Did Not Die, in which the systematic and institutional continuity of apartheid is illustrated.

Furthermore, the approaches, political strategies and programmes of AZAPO, ANC and PAC were fundamentally different, as they still are to date; they never “had an identical aim” as asserted by Ka-Soko. Equally irreconcilable are their visions of a liberated Azania.

The current national discourse land attests to the resilience and relevance of the Afrikanist ideas Sobukwe championed more than 40 years ago. Unwavering in his Afrikanist position on the return of the land robbed, annexed and appropriated by settler colonialists, Sobukwe repeatedly proved the righteousness of his ideals to all state agents, journalists, and investigators who visited him on Robben Island and in Galeshewe during his incarceration and banishment.

In asserting and affirming Sobukwe’s legacy today, as suggests Ka-Soko, we must also go beyond the usual simplistic and narrow biographic approaches and narratives and excavate the depth of his intellectual prowess and engage with his ideological and philosophical propositions and fulfil his vision of a liberated Afrika.

It is not enough to lament Sobukwe’s calculated systematic and institutional exclusion and silencing, even under the so-called democratic “black government” – and it is not enough to recite his biography, however obscure it may be; we must delve into, interrogate, unpack and dissect his intellectual, political and philosophical ideas wherein lies his immortality.

This is the challenge to the black intelligentsia, Afrikan scholars, political fraternities, contemporary activists and media practitioners alike.

We must affirm Sobukwe’s legacy, do justice to his indelible memory and dispel all the lies and misconceptions that obscure his noble character and Afrikanist personality.

Sobukwe is a visionary and a philosopher par excellence. No clandestine or overt political agendas can erase his name or blot out his memory.

* Thando Sipuye is an Afrikan-centred historian and activist. He is an executive member of The Ankh Foundation and the Blackhouse Kollective in Soweto. He writes in his personal capacity.